A look at some of what the left was writing and reading in that transformative year for U.S. labor, 1934.

‘Revolutionary Literature of 1934’ by Granville Hicks from New Masses. Vol. 14 No. 1. January 1, 1935.

IT HAS been a good year, an exceptionally good year, a year to put the Menckens, Hazlitts and Soskins on the defensive. Before 1934 it required some understanding of literary and social processes to recognize the promise of revolutionary literature, but now even a daily book reviewer has to blindfold his eyes to ignore its achievements and its potentialities.

The drama has made the most startling advance. The amorphous rebelliousness of the New Playwrights has yielded to the strong, clear-cut, revolutionary intelligence and discipline of the Theatre Union, depending for its support not on the whims of dilettantes but on the eager enthusiasm of workers and their organizations. Founded in 1933, the Theatre Union not merely achieved popular backing in 1934, but demonstrated maturity in authorship, directing, and acting. The eloquent but confused Peace on Earth was followed by Stevedore, rich in its conception of character, firmly integrated in construction and method, and revolutionary in its understanding of social forces. Melodrama the bourgeois critics called it, unable to deny the effectiveness of Peters’ and Sklar’s writing and Blankfort’s directing, but they could point to no distortion of character or event for the sake of sensation. The term was their unconscious tribute to an alive and exciting play.

Aside from the Theatre Union plays, we have John Wexley’s They Shall Not Die, a kind of experiment in dramatic journalism, most effective when it follows most closely the actual events of the Scottsboro case, least effective in its invented scenes. It might have been a better play if it had been written for the Theatre Union rather than the Theatre Guild. A dramatist cannot rise very far above the intellectual level of his audience, and the Guild audience is, in matters such as the Scottsboro case, singularly ignorant. Yet Wexley made it a moving play, and the enlightened spectators knew that he under- stood the true issues.

Nineteen thirty-four has also brought the publication of books of plays by John Dos Passos and John Howard Lawson. Neither author has wholly escaped from the mannerisms of the New Playwrights era, but the former’s Fortune Heights and the latter’s Gentlewoman show not only talent but growing clarity. Melvin Levy’s Gold Eagle Guy, which I have not seen, has divided critical opinion. Samuel Ornitz’s In New Kentucky, soon to be produced, is, if one can judge from the first act published in THE NEW MASSES last spring, a forceful and authentic portrayal of working-class life. Finally, we must note the activity of the workers’ theatres and the progress of dramatic criticism in the thriving magazine, New Theatre.

The poets, I think, are getting away from the kind of obscurity that marred the work of so many of them. Robert Gessner’s Upsurge is direct enough, and taken as a whole it gives a sense of the urgency and irresistibility of the revolutionary movement, though taken line by line it is disappointingly diffuse. Isidor Schneider’s poems in Comrade-Mister, on the other hand, are firm and strong, and a second reading finds them more impressive than a first. He has sacrificed none of the originality and profundity that distinguished his earlier work, and he has added to them strength and clarity.

It is impossible, of course, to mention all the poetry, even all the good poetry, that has appeared in the periodicals. I remember particularly Alfred Hayes’ Van der Lubbe’s Head and his May Day Poem, Alfred Kreymborg’s America, America, Stanley Burnshaw’s parody of T.S. Eliot, and Kenneth Patchen’s poem on Joe Hill.

Two revolutionary poets that seem to me to have developed materially in 1934 are Kenneth Fearing and Edwin Rolfe. The latter’s Unit Assignment in The New Republic, is an excellent example of clarity achieved not by oversimplification but by the extension and integration of the poet’s experience. It is richly personal and full of sharp poetic perception and at the same time broad in appeal and free from literary echoes.

A definitive list of good short stories is as impossible as a definitive list of good poems. The work of Meridel Le Sueur, Louis Mamet, Erskine Caldwell, Alfred Morang, Fred Miller, and William Carlos Williams is particularly memorable, but there are many others whose stories deserve examination. My general criticism of proletarian short story writers is that they limit themselves too persistently to incidents of suffering or frustration. These are well adapted, of course, to the short story form, and there is every reason for portraying the cruelty and barrenness of life under capitalism, but there are other subjects as worthy of attention, and the danger of monotony could easily be avoided.

Two collections of short stories deserve at least a word. James Farrell’s Calico Shoes and Other Stories is open to the same general criticism as his Young Manhood of Studs Lonigan, of which I shall speak later. No one, however, can deny the gruesome horror of such stories as The Scarecrow and Just Boys or the pathos of Honey, We’ll Be Brave.

Langston Hughes’ Not Without Laughter was more disappointing than Calico Shoes because I had expected more. After the militant clarity of some of Hughes’ poems, the confusion of most of his stories–his emphasis on situations and events that the revolutionary must regard as of only secondary importance–was something of a shock.

Criticism has to be discussed in terms of the revolutionary journals. Week after week THE NEW MASSES has reviewed books in all fields written from all points of view. Often the reviews have not been so good as they should be, but on the whole they have cogently and intelligently applied Marxist principles. The reviews here and in other revolutionary periodicals have made Marxist criticism a force in the literary world. It is worth observing also that the best reviews that have appeared in any non-revolutionary publication in 1934 have been written by a fellow-traveler, Malcolm Cowley.

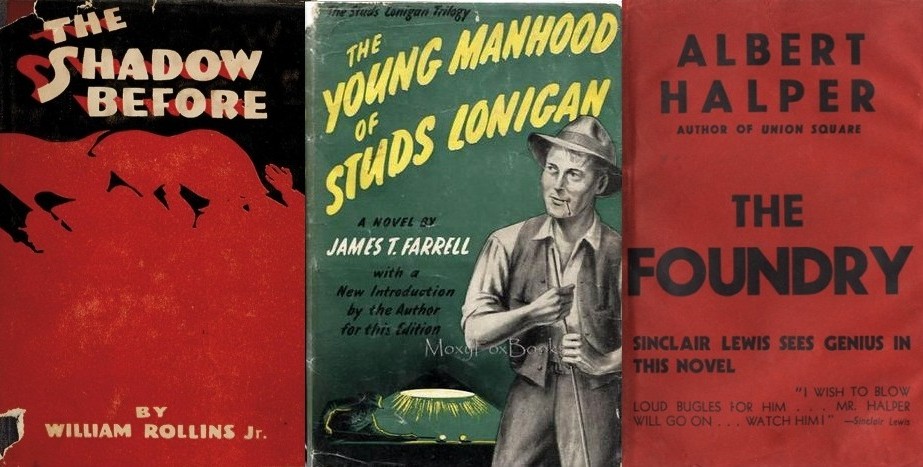

The revolutionary novels deserve detailed consideration, because they have attracted so much attention, and they lend themselves to it. Here are the novels published in 1934 by avowed revolutionaries or close sympathizers: Parched Earth, by Arnold B. Armstrong; The Shadow Before, by William Rollins, Jr. The Last Pioneers, by Melvin Levy; The Land of Plenty, by Robert Cantwell; The Great One, by Henry Hart; The Death Ship, by B. Traven; The Young Manhood of Studs Lonigan, by James Farrell; Slow Vision, by Maxwell Bodenheim; A House on a Street, by Dale Curran; The Foundry, by Albert Halper; Those Who Perish, by Edward Dahlberg; The Death and Birth of David Markand, by Waldo Frank; Babouk, by Guy Endore; The Executioner Waits, by Josephine Herbst; and You Can’t Sleep Here, by Edward Newhouse.

Some of the novels are revolutionary only in a rather broad sense of the word. Tess Slesinger recognizes the sterility of bourgeois culture, apparently sympathizes with the revolutionary movement, and has sense enough to prefer real revolutionaries, or doesn’t know any well enough to put them in her book, The Unpossessed. She is herself rather too close to the futile chattering about revolution she satirizes, and her New Yorkerish wise-cracking becomes tiresome. Like Albert Halper, when he wrote Union Square, she tries to satirize the neurotic fringe before she has acquired the knowledge of the essential revolutionary movement that would make it possible to see the fringe in true perspective. Yet her talent is unmistakable, and even though her novel is as much a symptom as it is a portrayal of the fringe psychosis, sincerity manifests itself above the wise-cracking. One can hope she will follow the path of Halper.

James Farrell’s position cannot be questioned as Tess Slesinger’s can; everyone knows where he stands. But The Young Manhood of Studs Lonigan pretty much disregards the insight Marxism can give into the psychology of the petty bourgeois. Lonigan, a potential gangster, is interpreted chiefly in terms of sex urges and religious influences, which are not to be ignored but, taken by themselves, offer inadequate explanations. Farrell’s novel comes to seem a mere transcript of observations, almost without proportion or emphasis. Despite the fact that he has written three novels and a book of short stories, I have a curious sense that Farrell is still in a preparatory stage. He has extraordinary powers of observation and a remarkable memory, but his sense of human values is distorted. That he will develop into a clear and powerful writer I do not doubt, but I sometimes wish he would hurry up.

Guy Endore’s Babouk is an historical novel, and the very idea of an historical novel written from a Marxist point of view is exciting. Many scenes in Babouk are memorable, and it is a magnificent indictment of one of the cruelest phases of human exploitation. As in many historical novels, however, the documentation is so profuse in some portions that the story stands still. Moreover, as Eugene Gordon pointed out in his review, Endore, especially in his eloquent and challenging last chapter, treats the race issue as if it were a simple conflict between black and white.

All three of these novels are important to the revolutionary movement because of their author’s varied abilities. Tess Slesinger’s wit, James Farrell’s precision, Guy Endore’s gift for research and for imaginative re-creation of the past-these are qualities that ought to enrich revolutionary literature. At present, however, these writers seem to stand a little apart from the struggle. It is not merely that they deal with marginal themes; they deal with them in a marginal fashion. Greater unity in their work, better proportioning, and a sharper, truer emphasis can come only through deeper understanding, and that is something Communism can give them.

I have said many times that the Marxist critic should not attempt to prescribe the subject-matter of revolutionary novels. It is the author’s attitude that counts, not his theme. But I believe that there can be no greater test of an author’s powers than an attempt to face the central issues of his time where they are most sharply raised. I want to turn, therefore, from the three marginal novels I have just considered to The Shadow Before, The Land of Plenty, and The Foundry. Merely writing about a factory does not make a good book, but any author who attempts to depict the class struggle in its most acute form deserves respectful consideration.

Both The Shadow Before and The Land of Plenty have been so widely–and so deservedly–praised that I shall take their virtues for granted and speak chiefly of their faults.

It was pointed out to me by a labor organizer that The Shadow Before, by transferring details of the Gastonia strike to a New England setting, portrayed a situation that is true to neither section. This, I am afraid, indicates the great weakness of the book: it is to a certain extent synthetic. I feel, for example, that the neuroticism of Mrs. Thayer and her daughter, though possible enough, is not representative. The book does not give an accurate cross-section of the various classes in a mill town. Rollins did not know enough to do what he so ambitiously attempted. He had to fit together fragments of knowledge. Even the method, which owes a good deal to Dos Passos, does not always have an organic relationship to the material. One can say all this and still grant the effectiveness of the book, which, through the author’s accurate insight into certain fundamental issues and his warm sympathy, transcends in general its particular weaknesses, and rises to a stirring and altogether convincing climax.

The first part of Cantwell’s Land of Plenty has none of the faults of The Shadow Before, and I rank it as the finest piece of imaginative writing the revolutionary movement in America has produced. The second half, however, is less satisfying, and for reasons akin to those that explain the imperfections of Rollins’ novel. Cantwell gave a frank account of his difficulties in a letter to THE NEW MASSES last summer: he simply did not know how such a situation as he had portrayed would work itself out in real life, and he deliberately blurred and confused the ending to conceal his ignorance.

This is clearly a case in which half a loaf is a great deal better than none, and Cantwell deserves to be praised for what he accomplished, rather than censured for what he failed to do. But both The Land of Plenty and The Shadow Before make it plain that a revolutionary novelist has to have very exact knowledge. Lafcadio Hearn pointed out many years ago that a magnificent novel might be written about Wall Street, but that no novelist ever got a chance to know enough to write it. The labor movement is quite as complicated as Wall Street, and when a first-rate novel, first-rate from start to finish, is written about it, its author will have to be more than an observer of the class struggle.

For that reason Halper may have been very wise in limiting himself as he did in The Foundry. The Foundry is less good than the first half of The Land of Plenty; it depends on the rather heavy-handed amassing of details instead of such shrewd and sound selection as Cantwell practises. Yet Halper–like Dreiser, whom he so strikingly resembles–gets his effects. Even a good deal of bad writing, and the choice of details that are merely picturesque, rather than revealing, cannot do more than slightly blur Halper’s picture. We see the men and the bosses, and we feel the struggle that goes on between them even in this relatively peaceful shop. It is probably true that a less cautious writer would not have stopped where Halper did, just at the point at which Heitman’s predictions of an intensified struggle are coming true, but it was better for Halper to stop there, to recognize his limitations, than to plunge into depths from which he could not extricate himself.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1935/v14n01-jan-01-1935-NM.pdf