Nathan Adler recalls rebellions of the enslaved in New York City during the 1700s as early instances of the long tradition of the rebellion of working and oppressed peoples on the continent.

‘An American Tradition’ by Nathan Adler from New Masses. Vol. 10 No. 10. March 6, 1934.

THE pirate gentlefolk who rule America have nurtured many myths. It has pleased them especially to speak and write of the essential American spirit of rugged individualism, to insist upon every occasion, that collective bargaining is alien to an American culture.

When the American revolutionists rewrites history, however, they will dispel this “sacred” and obscuring aura. They will write of the maximum wage law of two shillings a day that was introduced but one year after the revolution of seventy six. They will write of the early Conspiracy Laws that were utilized to break strikes: there were many strikes in the golden, democratic days. They will tell of the bayonetted militia sent against picket lines in the days of Washington and Jefferson. Searching back long before that merchant struggle for the free market (which has been called the American revolution), the working-class will find its heritage; struggle and solidarity: their bones in the prisons, their blood soaked deep in the deep American soil. New York in 1741 was an idyllic country. The burghers walking along the sea wall at the Battery watched the fishermen lolling on the bay. Back from the bay rolled the tranquil Brooklyn hills. The bell buoy rolled gently on the waters, chiming an angelus for the gulls.

The righteous, Christian burghers strolled contentedly past the fort, past the sea wall, glancing with approval upon their city. It crept, tendril-like, from the bay, spreading to the farm country near Chambers Street and beyond it to Canal Street and the deep woods, and the wilderness.

But an idyllic country does not change a boss. A pastoral tranquility won’t check a wage cut. In 1741 the journeymen bakers of New York struck. The leaders were arrested, convicted of a conspiracy not to bake bread, and the strike was broken. Little more is known. The masters save few of these early documents.

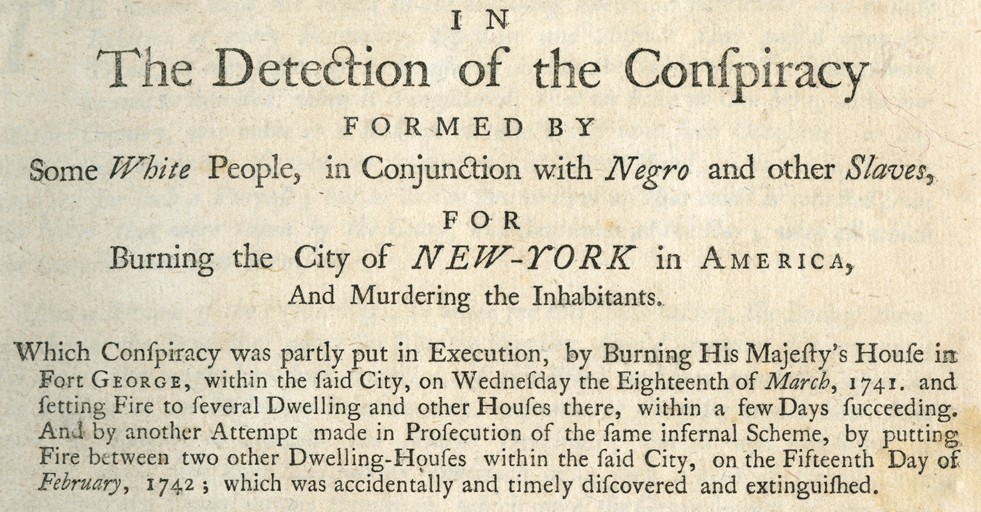

That same year the Negro slaves rebelled. It was the struggle of a people young in revolutionary experience. Their methods foreordained their failure. It is as our heritage, as our American tradition of struggle, that we must view these early days.

There were ten thousand people in the city of whom more than one fifth were Negro slaves. Unlike the southern plantation, where one group was isolated from another by many miles, the New York Negroes found it easy to communicate with one another and with the sailors from the ships that entered the harbor. They lived as an organic social group.

The burghers feared their slaves and punished them for the slightest offenses. The gentlefolk remembered 1712; they could hear the sputterings of this young flame, and dreading the consequences, enacted stringent laws prohibiting Negro assemblage.

On April 7, 1712, between one and two o’clock in the morning, the home of Peter Van Tilburg had been set on fire as a signal for a general Negro revolt. The white merchants, as they ran towards the blazing building, saw a band of Negroes in the flamelight. Armed with guns and knives they were grouped before the Van Tilburg house. Other Negroes, kept running up and, presenting a solid front, the slaves faced their white masters before the burning house.

Gunshots ripped through the night, knives were wielded. Some whites ran to the Governor at the Battery. A cannon was fired from the ramparts to arouse the town. The soldiers, wakened, marched to the house, their bayonets gleaming under the flame red sky. The slaves fought bravely till they saw the bayonets glitter in the firelight. Outnumbered, the Negro fighters fired one last volley and retreated north into the forests.

Pursued by the soldiers and the white mob the Negroes made for the woods and swamps. Many buried themselves in the deeper forest near Canal Street. Many were taken prisoners, some killed themselves rather than return to the custody of the whites. Exactly how many were captured and killed is not known, but the number must have been great. “During the day,” the historian writes, “nineteen more were taken, tried, and executed.”

If the burghers remembered 1712, so did the slaves. During the winter of 1741 (England was at war with Spain) a Spanish vessel had been captured. The crew, for the most part Negro, had been put up at the auction block and sold into the town. The floggings they received served only to fan the discontent that sputtered and smouldered in the city.

March the eighteenth was a wild, blustering day. The governor’s house in the fort was found afire. Fanned by a fierce wind the flames spread to the King’s Chapel, to the secretary’s home, to the barracks and the stables. The entire fort was on fire! The fire was supposed to be an accident; no evidence of a plot could be found.

A few days later the home of Captain Warren, near the fort, was found ablaze. Two or three days after, the storehouse of Van Zandt went up in smoke. Still there was no general suspicion. Three days more–a cow stall burned down; a few hours later the home of Thompson. In this case the fire originated in the room where a slave slept. The next day live coals were found in the stable of John Murry on Broadway. Evidently, these fires were not accidental. The incidents of the past week arranged themselves into a pattern. The whites were thoroughly frightened.

Soon after, the home of a sergeant living near the fort, burst into flame. That same day a dwelling in Fly Market became a fire box. A Negro belonging to a prominent citizen leaped from the window as smoke began curling from the house. A shout was set up and he was pursued. He vaulted the garden fence and ran for the woods.

At about this time, a Mrs. Earle who lived on Broadway, said she had been sitting at her window one afternoon and saw three Negroes strolling up the street. A light breeze brought some of their words to her. She heard one say, “Fire, fire, scorch…a little down bye and bye.” She reported this incident to her aldermen who carried it to the justices. The whites were panic stricken. One of the Spanish sailors was questioned; his answers were unsatisfactory and elusive and the entire crew was arrested and thrown into jail.

While the magistrates were in session that same afternoon, the cry of fire ran again through the town. The militia was called out and sentries were posted on all streets. The whites became panicky and hysterical; they packed everything of value they possessed and began a hurried exodus from the town. Anything that had wheels was seized. Belongings were gathered, families were bundled into wagons and carts, and the hegira towards the farms beyond Chambers Street was in full progress.

The town authorities, too, were panicky. They herded all the slaves into jail; Negroes of all ages–children of ten and old women of seventy. The court was convened but no proof of conspiracy could be established. A reward of one hundred pounds and full pardon, was offered anyone who would turn state’s evidence.

On April 21, the court sat with Judges Phillips and Horsmander presiding, and a jury was impanelled. There were many prisoners but there was not enough evidence to bring even one man to trial. Among the first to be examined was Mary Burton, a young servant girl. There were rumors that she had spoken of a rendezvous in a Negro tavern near the Hudson River.

When she was brought before the Grand Jury she refused to be sworn. She was threatened, but with no success. promised pardon and protection, the judges attempted to bribe her, showing her the money. She spat on their money, showing an independence and strength that won the admiration even of the white jury.

Finally she was ordered back to jail. Terrified, she consented to be sworn. After taking the oath she refused to say anything about the fires. The judges appealed to her, they painted the terrors of final judgment and the torments of Hell; with unctuous voices they played upon the ignorance and superstition. they had inculcated into this brave young Negress. They beat in on her insistently, painting picture after picture, each more terrifying than the one that had preceded it. Finally, half-hysterical, she spoke.

She told of slave meetings at the tavern; of plans to make a “country of their own.” It was the plot of 1712 again.

May 11, the executions began. Caesar and Prince, two Negroes that Mary Burton had implicated, were hanged in chains. The bodies were left on the scaffold as a lesson to others.

Quack and Cuffee, two others, were the first to be burnt at the stake. Curious crowds gathered to see the building of the stakes, stared at the wagon loads of wood drawn through the streets, watched the men pile the faggots under the blue Spring sky. The mob faggots under the blue Spring sky. The mob lingered till the curling smoke hid the two black bodies, they hung delightedly on every scream and shriek till the fires screamed no more.

Through Mary Burton’s confession 154 Negroes were jailed. Two by two, on the scaffold, at the stake, they were murdered because they dared dream of freedom, of “a country of their own.” “Some died laughing,” the records say, “mocking the crowds that came to watch.”

The bodies swung in the June air, in full view of the fishermen lounging on the bay. Through three weeks of sunshine and storm the bodies dangled and twirled like limp censers. Under the heat of the sun they bloated and decomposed; they began to drip. The stench of rotting flesh, the drip, drip, drip of decaying bodies–flesh and blood of workingmen–was soaking into American soil, becoming American soil. America had been baptized.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1934/v10n10-mar-06-1934-NM.pdf