As is the case today, in the early 1900s the existing labor movement was completely unprepared for the momentous changes happening in production. The rule of large-scale finance capital wrought took decades for unions to come to organizational and political terms with. Henry Ford’s vertical and horizontal production and distribution model was as much of a challenge as his vehement anti-union policies. Stanley Boone reports for the T.U.E.L. on Ford’s growing empire. It would be almost two decades after this that Ford signed, under great duress, his first union contract.

‘The Ford Industries’ by Stanley Boone from Labor Herald. Vol. 2 No. 4. June, 1923.

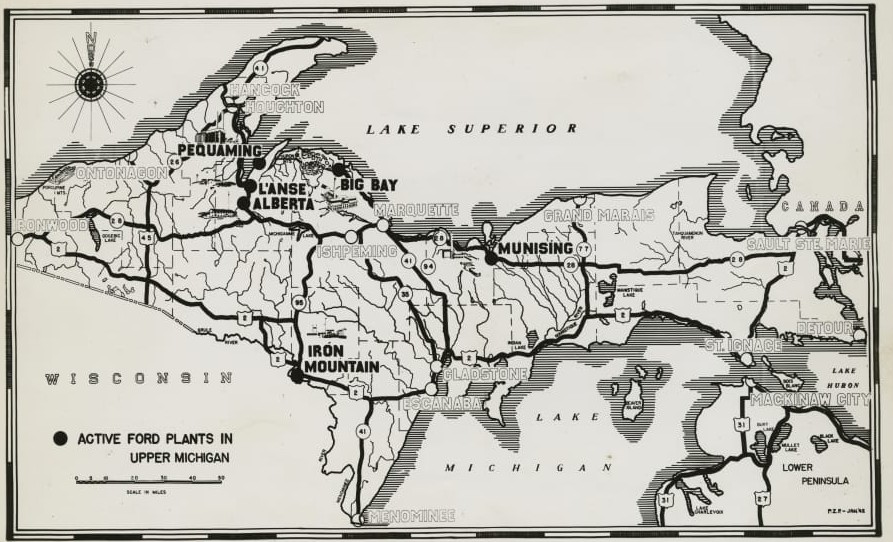

SHIPMENT southward of iron ore will soon begin, ore taken from a small mine at Michigamme, in the Northern Peninsula of Michigan. This used to belong to the Cleveland-Cliffs Company, but had not been operated for years. Its reopening marks a new advance of one of the most significant industrial experiments ever carried on in the capitalist system. The mine at Michigamme belongs to Henry Ford.

The significance of the Ford industries, for the purpose of this study, is that this capitalist is building, against the combined opposition of some of the most powerful financial and industrial interests in the United States, the frame-work of an industrial community the aim of which is to be completely self-supporting. He is coordinating land, coal, iron and the manufacture of machinery, with the accessories of an industrial colony, on a scale of the first magnitude. The Ford industries are peculiarly significant in connection with the movement toward trade union amalgamation, in which more and more thousands of workers are enrolling.

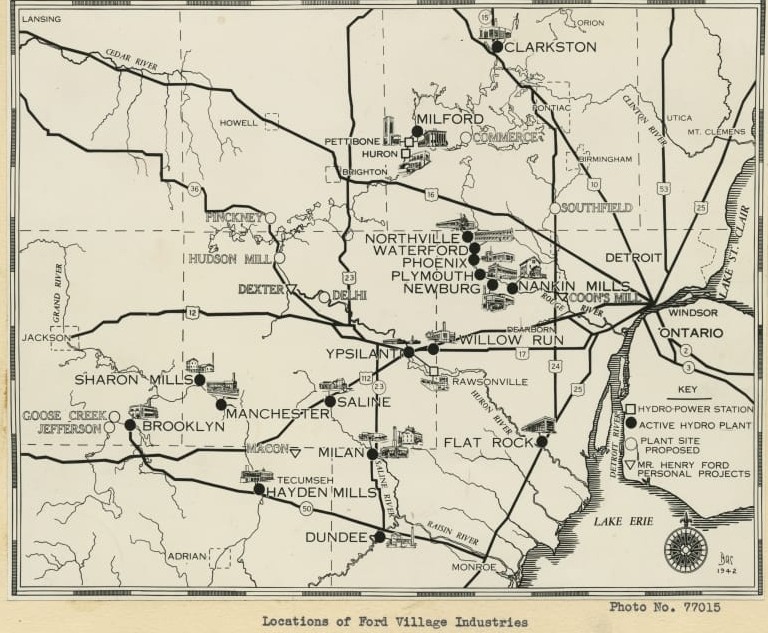

Ford’s Northern Peninsula holdings total, it is reported, 400,000 acres and contain rich iron deposits. The ore from the Michigamme mine will be shipped by rail to Escanaba, and from there by boat, a three days’ trip through upper Lake Michigan, the Straits of Mackinac, Lake Huron, the St. Clair River, Lake St. Clair, and the Detroit River, to the blast furnaces in Springwells, a suburb of Detroit. There the ore is converted into steel by a Ford process. The steel is used for the manufacture of tractors at Dearborn, a second suburb of Detroit, and of automobiles at Highland Park, a third suburb.

Ford’s railroad, the Detroit, Toledo, and Iron-ton, thus far runs only southward from Detroit. It connects his blast furnaces and shops with his own coal deposits in Kentucky. There is still a short link missing in this chain, where another line has to be used for a few miles. But Ford will no doubt not rest content until his own rail roads connect all of his plants and sources of supply.

Ford began business not many years ago as an automobile manufacturer on a very small scale. Today he has the Ford Motor Co., at Highland Park; the Ford blast furnaces at Springwells; the Fordson tractor plant at Dearborn; the Ford farm at the same place, with the Ford grain elevator; the Dearborn Independent, a weekly newspaper; the Ford Hospital at Detroit, the largest for hundreds of miles around; the iron ore beds in the North; the coal fields in the South; the timber; the D.T. & I. Railroad; and the possible nitrate and hydro-electric power at Muscle Shoals which he seeks by concession from the Government.

If Henry Ford extends his railroad, as is expected, his own rails plus his boats will connect the blast furnaces with iron and coal. These furnaces, situated midway between the two basic minerals, are virtually on the site of the automobile and tractor plants. His tractor plant is in the center of his productive land, where the tractors cultivate grain and fruit, and haul it to market and elevator. Timber and dairy products are the next development here. There is the possibility that his railroad will connect the Michigan land with Muscle Shoals fertilizer, with the added feature of railroad electrification and barge communication with the Gulf.

All of this is but the broad outline of a picture which is already being filled in with a thousand and one details. Ford’s industries manufacture coke, gas, tar oil, and other by-products, and benzol for fuel in tractors and automobiles. Ammonia nitrate is produced from his coal also, which is used as fertilizer. He builds houses for his workmen, and conducts paternalistic general stores. Water works, hydro-electric power, and other utilities are provided for “his communities.” Centralization of the entire system will be obtained through one huge office building which is to be erected at Dearborn this summer.

Much has been said about the speed-up system used upon the workers in the Ford Industries. A great deal of this is no doubt true. With the high degree of standardization of the industry, and the gearing of the whole process to a machine-like precision, the Ford system gets a maximum of production from each worker. In this matter the Ford industries are like all others in forcing the workers to produce to the point of fatigue. Its greater production is largely, however, the result of the system.

Where the Ford factories do differ from others is in the conditions under which the men work. They are cleaner and lighter than almost any others. The hazards are fewer. There are better facilities for medical and surgical aid. At the little mine in Michigamme, it is reported, the workers have shower baths, steel lockers, and a clean place to eat. Ford has found that it is profitable to make the workers a bit more comfortable.

The establishment of such conditions by Ford, on the basis of successfully continuing his great profits, is a demonstration that there is no excuse whatever for the intolerable conditions found elsewhere throughout the American industries. The capitalists of the country have not even the excuse that they are protecting their profits by continuing the terrible conditions that exist in the coal mines of America and in the mills of the Steel Trust.

All that has been said is merely an introduction to another study still to be made. The development of the Ford industries places many grave problems before the labor movement. The trade unions have been almost completely excluded from Ford’s plants. The automobile industry as a whole is almost entirely non-union. Along with the Steel Trust, it is one of the strongholds of the “open shop” forces of America. Like the steel industry, it will be organized only by new and modern methods. The labor movement must seriously face and understand the tremendous forces against them.

The further additional problem presented by the Ford industries is the overlapping and consolidation under one management of various industrial fields. This indicates that in order to handle the automobile industry, not only it is necessary for Labor to be organized industrially, but it will even be necessary to have a complete co-ordination of the forces of Labor over the several industries which, in the case of Henry Ford, have been completely brought under the domination and control on the side of Capital into one of the most gigantic Trusts that has ever been seen. And it is also a promise to the workers, of the wonders that technical advancement in industry can be made to perform in relieving the conditions of labor when finally the workers have taken over the ownership and control of the instruments of production.

The Labor Herald was the monthly publication of the Trade Union Educational League (TUEL), in immensely important link between the IWW of the 1910s and the CIO of the 1930s. It was begun by veteran labor organizer and Communist leader William Z. Foster in 1920 as an attempt to unite militants within various unions while continuing the industrial unionism tradition of the IWW, though it was opposed to “dual unionism” and favored the formation of a Labor Party. Although it would become financially supported by the Communist International and Communist Party of America, it remained autonomous, was a network and not a membership organization, and included many radicals outside the Communist Party. In 1924 Labor Herald was folded into Workers Monthly, an explicitly Party organ and in 1927 ‘Labor Unity’ became the organ of a now CP dominated TUEL. In 1929 and the turn towards Red Unions in the Third Period, TUEL was wound up and replaced by the Trade Union Unity League, a section of the Red International of Labor Unions (Profitern) and continued to publish Labor Unity until 1935. Labor Herald remains an important labor-orientated journal by revolutionaries in US left history and would be referenced by activists, along with TUEL, along after it’s heyday.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborherald/v2n04-jun-1923.pdf