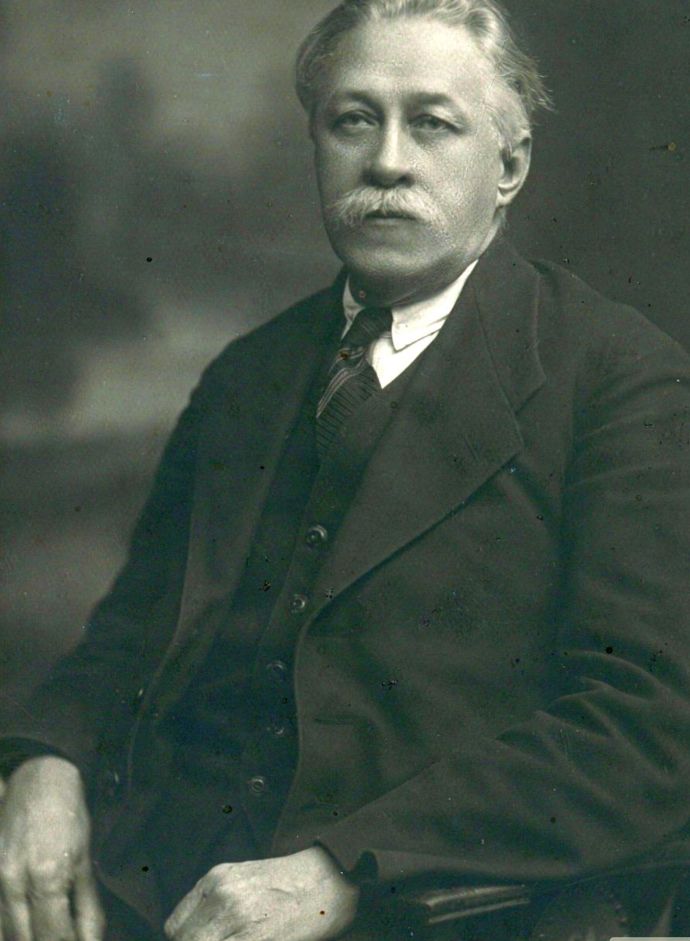

An important statement on how the early Soviets viewed the work of justice from one of its legal architects. A leading figure of the early Soviets, Stučka, born in 1865 became a lawyer in 1888 when he also entered active revolutionary politics. A central figure of the Latvian workers movement for two decades, who helped organize the crack Latvian Rifleman in the seizure of power in October, 1917 then became the Chairman of People’s Commissars for the short-lived Latvian Soviet Republic of 1918-1919, then the lead jurist of the early Soviet Union as People’s Commissar of Justice, helping to write the new legal Civil Code before becoming President of the Supreme Court of the RSFSR from 1923 until his natural death in 1932.

‘Proletarian Class Justice’ by Pēteris Stučka from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 2 No. 65. August 5, 1922.

We often find even in Communist papers, protests against class justice in general, and not against bourgeois or feudal class-justice. And we often speak of Right in general instead of speaking of Class Right. “Advance, you who honor Right and Truth”, we hear enthusiastically sung without properly considering what this Right actually means.

It required a political trial to bring all these questions to the fore. I refer to the trial of the Social Revolutionaries. A Tribunal whose president openly declared that it exercised class justice, proletarian class justice! A tribunal before which deputations of revolutionary workers appeared and pronounced their opinion, not upon the defendants as persons but upon the political party seated in the dock, upon the party calling itself Socialist! An undisguised class justice whose class character was further intensified by the direct pressure of the proletarian masses. One group of defenders after the other forsook their posts; first the “Socialists” (Vandervelde and Co.), then the one-time Socialists, Muravyev and his like.

From the lawyers nothing else was to be expected. Legal ideology is bourgeois ideology par excellence. This has been clearly demonstrated by no one less than Fr. Engels (in 1887 in the Neue Zeit in a joint article with K. Kautsky: “When the Christian Weltanschaung was obliged to depart, the legal or bourgeois Weltanschaung stepped into its place. And this Weltanschaung dominates not only the lawyers, Socialists and even Communists not excepted, it prevails also in the heads of laymen and even of broad proletarian masses.

What is Right? Consult the maze of legal writings, search the dictionaries, etc., and you will find the short and concise answer, that there is as yet no general conception of Right, that the legal authorities seek for it in vain. And I tell you that there cannot be such a conception as long as jurisprudence prates of eternal right and eternal justice, instead of accepting the class standpoint and recognizing Class Right, “a system, an order of social relations which correspond to the interests of the ruling class and will therefore be maintained by the organized power of this class, the state.” Can bourgeois society openly acknowledge this class right? No, it cannot do it, for it would be a recognition, a legalization of the proletarian revolution. The working-class and its ideologists must openly proclaim this, for that is their vital interest.

From this, and from this standpoint only, can we comprehend how it comes that the bourgeois lawyers glorify the murder of Liebknecht, Luxemburg and other Comrades, or are able to treat even the murderers of Ministers, as for instance of Erzberger or Rathenau, with great indulgence, and on the other hand speak of judicial murder when the Soviet government brings to trial the political assassins who kill proletarian leaders and proletarian state functionaries. And we will then be able to appreciate the same views within the ranks of the social-treacherous defenders or perverters of Right.

In one of his early writings, Karl Marx proves that it would be a logical absurdity to speak of impartial judges, because right and law are themselves partial. To the opposing class all class justice will appear unjust; there is no common understanding. And it is mere hypocrisy to estimate the justice of a sentence according to the outward formalities of the trial. But the whole of bourgeois justice swears by these formalities. These formalities are even in the best instances technical regulations for getting at the evidence and clearing up the question of guilt.

It is not these formalities which will determine whether a sentence is just or unjust, but the true facts and the class conception of Right. And particularly in the case of the trial of the Russian Social Revolutionaries it is not a question of such formalities. It is an unprecedented historical trial, in which it is not a question of persons but of classes and class groups.

Revolutionary proletarian class justice is not to be comprehended from the bourgeois conception of Right. But that does not by any means imply that this justice is quite undefined, that no law exists for it, but only personal arbitrariness. No, like every right, proletarian right also finds expression in law, in revolutionary decrees. It is true that the proletarian revolution abolishes all previous laws so far as they are not embodied in the new decrees. But that does not mean a sudden revolution of the consciousness of right in the people. This revolution is a protracted and difficult process. The retreat to the new economic policy which is naturally also a retreat on the legal field, has hampered it very considerably.

Proletarian class justice also means lawfulness, but only revolutionary lawfulness. It will hear nothing of formal objections on the part of juridical representatives who appeal to the law books of the overthrown bourgeois government and to the bourgeois legal authorities. And if (what has occurred nowhere else) foreign lawyers as Vandervelde and Liebknecht conferred in French or maintained silence in German, it was not because of linguistic reasons that they failed to be understood, but because they used the language of another class, the bourgeoisie. It was not class justice that was the objection here, but the fact that so-called proletarian representatives defended anti-proletarian class interests. It is not a question of a simple legal trial, but of a class struggle before the eyes of the working class of the whole world. And these labor leaders lend themselves, not to clearing the minds of the workers but to befogging them with bourgeois legal trickery.

Apart from the great importance of this trial for the cause of the world revolution, it will play an important part in enlightening the working class on the question of class right and class justice. Up to now we had no Marxist revolutionary conception of right and justice, and jurists, and non-jurists repeated the same old wisdoms of lawyer Socialists, which Engels censured as early as 1887. With us in Russia, the revolution introduced a certain change in this respect, but it would have been very desirable if this breach should have occurred outside of Russia before the revolution. The proletarian slogan is not “against class right and class justice”, but for proletarian right and proletarian justice! It would be more correct perhaps if the working class of Germany would oppose the bourgeois Supreme Court for the protection of the republic, with the slogan of a Workers’ Tribunal.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecor” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecor’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecor, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1922/v02n065-aug-05-1922-Inprecor.pdf