Here is a close–down to the individual–look I did at the changing economy, roles, and demographics of Ypsilanti’s live-in servants and part-time domestic workers. What makes Ypsilanti somewhat exceptional was its large pre-Great Migration Black community, by far the largest in Michigan by percentage at the time, and near total lack of European immigration during the early 20th century. While mainly an industrial town with early foundries taking advantage of the city’s Black labor, aside from a few isolated activists, Ypsilanti did not have an appreciable left or industrial union movement until the U.A.W. of the late 30’s. As late as 1910, nearly two million workers (over 91% of them women) were employed in domestic service. Constituting 8.5% percent of the workforce, and 2% of the entire population. With immigrants and Black women over-represented and therefor under-counted, those numbers are certainly higher. Dismissal of homework, Black and immigrant women, and women in general by the labor movement left these millions of proletarians ignored and unorganized by the official labor movement. Given that employment was often lone and for disparate private families, conditions were agreed upon individually, and masters were notoriously arbitrary, plus other issues made organization of domestic workers rare and difficult.

‘The Help: A Social History of Ypsilanti’s Live-in Domestic Workers, 1900-1910’ by Revolutions Newsstand (Matt Siegfried).

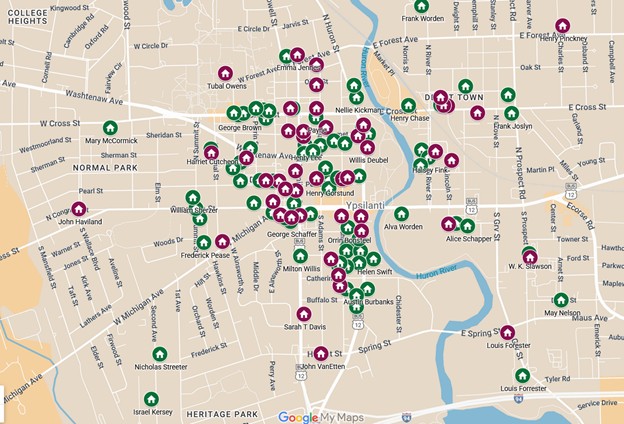

This map relies on the 1900 and 1910 Censuses and is only the briefest of local snapshots of that moment in our history when domestic workers in this country numbered in their millions. And Downton Abbey was not.

In an attempt to rescue from anonymity those thousands of working-class Ypsilanti women (and a few men) who worked as live-in domestics in the early twentieth century, I have created a map giving them names and looking at the homes Ypsilanti homes in which they worked and lived between 1900 and 1910.

The locations, labelled by the name of the head of household (owner), as recorded by the United States Census. Each location includes an address, name, gender, race, age, place of birth and title, if applicable, of live-in workers and can be accessed by clicking on the house icons. There are two layers, 1900 (green) and 1910 (purple) which can be viewed separately or simultaneously.

Click on the map for names and locations of domestic workers:

—

Everyone in Ypsilanti has seen the lovely Victorian-era houses, and one or two bona fide mansions, which populate the city. Ypsilanti spends a lot of time promoting that image and maintains large historic districts to protect that character. The families that lived in those homes are well-known, even now, to many in town. They were city founders and city fathers. They were rich. They were mayors. They have streets and buildings named after them. They have places in the histories we tell about Ypsilanti’s past. I must confess to, frankly, having extraordinarily little interest in them and their lives.

However, I also know that every one of those homes and families was cared for by others. By those who went to work because they had to, and doffed their cap when they needed to. Some of them were immigrants, but most were local. They appear in no history books, but were a part of, and made, history just the same. For them, I have great interest.

The vast majority of those who worked in Ypsilanti domestic service were white, as was the area at the time, women. However, and increasingly so, Black women worked not just at piecemeal domestic work, but as live-in servants and maids until Jim Crow and the general move away from domestic servants changed that.

—

Many Ypsi workers relied on the odd jobs and occasional tip by the extra work wealthier Ypsilantians sometimes employed them for. And often the rent went straight back to the man who hired them. They were people like my own ancestors, more than a few of which were such domestic workers.

The work done in service was mainly cooking, laundry, and cleaning, with some acting as nurse, childminder, or personal servants. Ypsilanti’s wealthy were rich by local standards, but not rich enough to afford the butlers, chauffeurs, gardeners, tutors, and handymen that were routinely employed by the wealthiest families in this country during that era–so we see little of that locally. (Ann Arbor on the other hand…)

All employment of live-in workers was, in part, a status symbol and fads always play a part in such symbols. To have a butler, valet, or live-in gardener was the height of status in the late 19th and especially early 20th centuries. Sometimes, as confirmation of one’s Americanism and prosperity, first generation immigrants hired the next wave of immigrants as domestic servants. It was not unusual for first generation Ypsilanti Germans of means to hire Irish women and girls as domestics.

—

It was of status in the United States if your butler was a white man, and for a while a Japanese man. A white man’s authority over women, immigrants, and Black people in this country is a given. But to have authority over another white man was, and is, a sign of extraordinary power. In the early part of the 1800’s it was highly unusual to have a native-born white person working as a domestic servant, which was seen as the work of immigrants and Black people.

That changed throughout the century as more white people ended up in certain services and service trades, often at the expense of Black workers and other groups (Black barbers and Asian laundry workers were pushed out of the few professions afforded to them).

As physical racial segregation became more rigid and severe, it became considered unseemly by many whites for a white family to have Black people living in their home, or even being in close proximity, and there was a turn by the wealthy to employ Asian immigrants and Latin Americans as well as whites for domestic work.

As the working class grew along with their aspirations, domestic work again became seen as both unworthy and a sign of a rejected class distinction for many. Changes and slowing of immigration also changed the character of those in domestic service. By the Great Depression, the world of live-in domestic workers, already in long decline, ended for all but the wealthiest Americans. And in that world, domestic work reverted almost entirely to Black people and immigrants of color.

In 1900, there was only one butler employed in Ypsilanti. A Black man, Lorenzo Pierce, served the Ainsworth family home. In 1910, there were two, both white men and aged. There were no valets or drivers employed in 1900. In 1910 there was one, Manchester Roper for the Quirk family. Manchester was a Black man in his fifties at the time and was a stalwart in the struggle to desegregate local theaters, often going to court in the matter. His wealthy boss, Daniel Quirk, was also into theater, but as a purveyor of blackface and minstrelsy. A microcosm of many of society’s divisions under one roof.

—

Many, many more people than shown here were employed to do piecemeal work, and much of this fell to Black women. Both white and Black women were door-to-door laundry workers, maids, servers, cleaners, cooks, wet nurses, and childcare workers for many Ypsilanti families in these years, with Black women confined to such work. Men, Black and white, were hired for lawn maintenance, repair work, as waiters, to accompany men on trips, to function as attendants and drivers, etc.

These relationships were not just those of informal family employer-employee; many leading Ypsilanti families also functioned as the biggest industrial employers in town, as well as the landlord, and often an Ypsilanti political leader too. Ypsilanti was an extremely close-knit, patriarchal community whose ruling families exercised their authority for generations.

In 1900, a working class Ypsilantian would have worked for the same family their parents did, even grandparents, and they expected their children would do the same. These workers often lived in a home owned by their employers, went to church where that family led, put money in their bank, and voted for them at election time. Generation after generation.

—

Here are a few facts I compiled in this process. In 1900, 87 Ypsilanti households employed 107 live-in domestic workers. Ten years later that number fell to forty-seven households and fifty-one live-in workers. The vast majority employed one servant, a few two, and the largest employer, Mary Savory, had three.

The vast majority of those workers were women. In 1900, of the 107 domestic workers 86% were white women, 11% Black women, and 2% Black men. There were no white men working as live-in domestics that year.

Fifty-five percent of those workers were born in Michigan (though a closer look reveals that a majority of those are children of immigrants), and 17% born in other states. By far, Canada was the largest foreign-born birthplace at 16%, with 5% from Germany, and the remaining 6% scattered between a half dozen northern European countries. In 1900, the average age of a live-in domestic in Ypsilanti was 25.4, the oldest was 67 (Harriet O. Culver, New York-born housekeeper for Mary Tucker) and the youngest fourteen.

In 1910, 47 households employed fifty-one live-in domestic workers. A dramatic decline from the previous decade. In part this is explained by a severe economic downturn that hit the city in the early 1900s, but primarily it is indicative of the larger trend away from domestic live-in help across the country.

Also noticeable are several other changes. White women’s share of the workforce has declined to 74%, while Black women’s rose to over 17%. Black men at 4%, and for the first-time white men show up as domestic workers, also at 4%.

Fifty-one percent of the workers were born in Michigan, over 17% in Canada, 23% were from other states, and reflecting Ypsilanti and Washtenaw’s noticeable (unlike nearby Detroit) lack of immigration in those years, only 8% were foreign-born (outside of Canada). The average age was also older, 33.27 years old with the youngest domestic worker being fifteen and the oldest 77 (white male, New York-born butler for Merlin Webb).