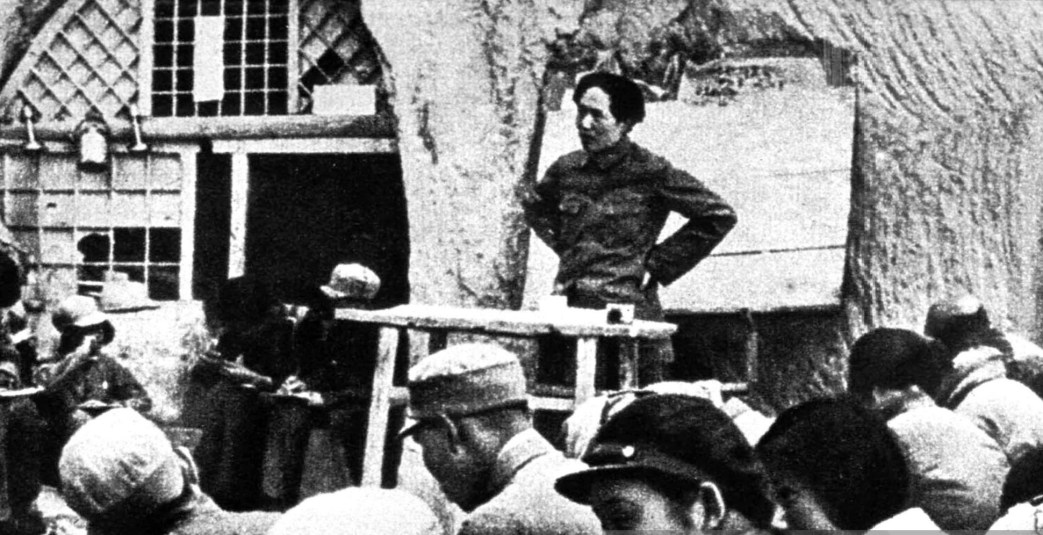

A defining text for what would become known as Maoism, this is one of–if not the first–works by Mao translated into English and widely published outside of China. So early in fact that Mao’s authorship is not stated in this, foremost magazine of the Comintern. Written while the KMT-CP alliance was still intact, if very shaky, Mao was dispatched to investigate the state of peasant populations and their anti-landlord, anti-warlord actions that broke out in the wake of the southern-based National Revolutionary Army under Chiang-Kai-Shek’s Northern Expedition against the comprador General’s regime of Beiyang. That year saw urban Communist strongholds and mass, well-established, working-class organizations annihilated in blood-soaked counter-revolutions in the most important cities. Many surviving activists were forced into the countryside, helping to reinforce Mao’s emerging peasant-based political and organizational strategy and his own rising position in the Chinese Communist Party’s leadership.

‘The Peasant Movement in Hunan’ by Mao Zedong from The Communist International. Vol. 4 No. 9. June 15, 1927

(A Report published in the central organ of the Communist Party of China, “The Weekly Guide,” 12th March, 1927.)

ON my return to China I made a tour from January 4 to February 5, through five districts of Hunan (*Hunan is a province more than twice the size of Ireland, lying between Canton and Hankow, and is not to be confused with Honan, further north) Tsiengsu, Siansian, Chunshan, Tsienlin and Changsha. I called meetings of comrades working among the peasants, heard their reports and discussions and in this manner received a good deal of material. I have seen things such as were never seen or heard of before. Since a similar state of affairs apparently exists in all provinces, the mistakes made there must be set right as soon as possible, and the sooner the better.

The rising surge of the peasant movement now constitutes an extremely vital problem. Before very long millions of peasants in Central, North and South China will rise and their force will be more terrible than that of a hurricane. No matter what force tries to stop it, it will have to give way before their onslaught in the struggle for freedom. The imperialists, the militarists, the old government officials, the gentry and the rich peasants will be swept off their feet. The question now arises; should we take the lead in this movement, or should we hang on at its tail and merely criticise? Everyone of us must make this choice, and be quick in doing so, too.

I shall now give an outline of my observations and ideas and let comrades judge for themselves.

They Begin to Organise

The peasant movement in Hunan province, extending from the south and central part of the province to all districts, can be divided approximately into two periods.

The first period, from January to September of last year, was a period of organisation. Between January and July it passed through an illegal period, and from July to September (with the arrival of the revolutionary armies), a period of open work. At that time there were about 300,000 to 400,000 members in the Peasant Leagues, which had direct leadership over one million people. There were at that time no struggles in process in the rural districts, and consequently there was no criticism. As the members of the Peasant Leagues worked for the armies as spies and guides, the military authorities thought highly of them.

The second period–from October, 1926 to January, 1927–was a revolutionary period. The number of members of the Peasant Leagues increased to two millions, and the number of people under their direct leadership to over 10,000,000 (at least one member of each peasant family belongs to a League).

About one-half of the peasantry of the Hunan province is organised in the Peasant Leagues; in the districts of Sianchu, Siansian, Luian, Changsha, Tsuilin, Ninsian, Pintsian, Sianin, Chunshan, Chunian, Mayan, Liansian, Anhui, etc., almost all the peasants belong to the Leagues and carry out their instructions.

The peasants have already strong organisations and have started to be active. We may say that during the four months, from October of last year to January of the current year, a great rural revolution has taken place.

Down with the “Gentry”

The main objects of the peasants’ attack are the gentry, rich peasants, the nobility, rural clergy, the old officials, the urban bureaucracy, and the rural money-lenders. The force of their attacks is “like that of a hurricane”; those who submit survive and those who resist perish. As a result, the ancient rights of the feudal lords and the nobility have been brushed aside and abolished. They “sweep the ground like the wind.” The power of the gentry is declining and the Peasant Leagues have become powerful organs, which carry into effect the slogan “All Power to the Peasant Leagues.” Even petty family quarrels are brought before the Peasant Leagues for settlement; and whatever the Peasant Leagues decide is law.

The Peasant Leagues carry on their activities in the rural districts according to the dictum “no sooner said than done,” and even outsiders say that the Peasant Leagues are all right. They cannot say otherwise. The gentry, rich peasants and the landlords are crushed; they dare not say anything against the Leagues. Some of them flew to Shanghai, Hanchow, Changsha, and other towns–those who remained in the villages join the Peasant Leagues.

Here are ten dollars–please accept me as a member of the Peasant League”–entreat the poor gentry. The peasants reply:

“Hm!!…Who wants your dirty money?”

A section of the middle and small landowners and middle peasants, at first opposed to the peasant unions, now want to join them. I went about a great deal and everywhere I met people who said to me:

“We should like the delegate who has come from the province to do us a favour and not enter us on the ‘special register.'”

(Under the former Tsin Dynasty (Manchu) two registers were kept of the population; the ordinary register and a special register. All decent people were entered on the “ordinary register,” whereas robbers, pillagers, and such like people were entered on the special registers.” This method is applied now in some places by the peasantry, who enter all those who are against the peasant unions on the “special register.”)

These people, of course, do not want to be entered on the “special register” and use every possible means for getting admission into the peasant union. They do not rest content until their names appear on the register of the peasant union, because the latter inflict severe punishment and do not give any peace to those whose name does not appear on the union register.

In the villages the peasants have disturbed the peace of the gentry. Village news goes from mouth to mouth and reaches the towns, and the urban gentry have also become alarmed.

When I got to Chansha, I met people there from various places, and listened to many conversations in the streets between middle and upper class people, including right wing Kuomintangers. In all these conversations, the expression “it is bad” or “it is very bad,” cropped up. And even progressive people say:

“Of course, all this cannot be otherwise in time of revolution, but nevertheless it is bad.”

It seems that it is impossible to avoid the expression “it is bad.” But is it really true?

Very Good and Very Bad

If we compare the present with the past, we see that the peasant masses have begun to fulfil their historical mission. The democratic forces of the countryside have begun to overthrow the feudal forces. And this overthrow of feudalism is precisely the real aim of revolution. Sun Yat Sen worked 40 years for the national revolution, and did not accomplish it; the peasantry have accomplished it in the course of a few months. They overthrew the patriarchal and feudal gentry, the rich farmers and big landowners, who held political sway for ages and who were the mainstay of imperialism, militarism and bureaucracy. Such a thing has not been heard of for thousands of years, but it has happened now and it is “very good”–not at all “bad” and certainly not “very bad.”

If we consider the whole question of the democratic revolution as a whole, the share of the urban population and of the army in it is 30 per cent. and the share of the peasantry 70 per cent. The expression “very bad” voices the views of the big landowners who attack the peasantry, it shows that these landowners do not want to part with the old feudal order. These views are an obstacle to the establishment of a new democratic order–they are counter-revolutionary views. Revolutionary comrades should not make use of this expression you are a person holding really revolutionary views, you should feel as you get into the rural districts that something extraordinary has happened: innumerable masses of peasant slaves have overthrown their exploiters, and this is “very good.”

“Very good” expresses the opinion of the peasantry and of all revolutionary parties. All revolutionary comrades should know that in a national revolution, big changes must take place among the peasantry. There were no such changes in 1911 and the revolution was defeated: now we have these changes, which is a fact of the utmost importance. All revolutionary comrades should defend and protect these changes, and if they do not do so, they are counter-revolutionaries.

“Going Too Far.”

Some people say:

“There must be peasant unions, but at present they go too far in their actions”.

This is the opinion of the “Centre Party.” But is it true to fact? There is certainly a certain amount of “disorder” in the villages. The peasant unions are very strong; they do not allow the big landowners to express their views, they have destroyed their forces, they have overthrown them and are treading them under foot. Sometimes it is said: if you have land of your own, you are a landowner. In some places peasants owning 50 mows of land are called “gentry” and those who wear a long gown are called “de-sheng” (nobles), and the cry is raised: “Enter them on the special register”. The gentry and the “de-sheng” are fined and punished; if they resist, their houses are raided, their pigs are killed, their corn is taken away and even the sisters and wives of the gentry and the “de-sheng” are kicked. If anyone goes out wearing a tall hat, he is put down as a “de-sheng.”

The views of the “Centre Party” have some justification, but in substance they are erroneous. First of all everything that has just been mentioned is applied only against the gentry, the “de-sheng” and the big landowners. Formerly they exploited the peasants, and now the peasants are paying them back. Wherever the gentry, the “de-sheng” and the big landowners exploited the peasants most, the reaction to this is strongest. The de-sheng” peasants are quick in recognising who is a and who is not, who is to be punished severely and who is to be treated leniently. That is why Tan Ming Yan said: “In nine cases out of ten, the peasants are doing the right thing when they attack the gentry and the ‘de-sheng.”

No Parlour Manners

Secondly, revolution cannot be carried on with drawing room manners; it is not like painting pictures or writing books–it is not as aesthetic as all that. Revolution is the rising of one class to overthrow another class. The peasant revolution is a revolution in which peasants overthrow the power of the feudal landowners. If the peasants do not make use of their full power, they will not be able to overthrow the power of the feudal landlords whom they have maintained for thousands of years. There must be a strong revolutionary spirit in the villages, for otherwise the peasantry cannot become a big revolutionary factor. All the above-mentioned actions, spoken of as “going too far,” originate in the strong revolutionary surge in the villages, in the national revolution, and this is absolutely necessary in the second period (the revolutionary period) of the peasant movement. In the course of the second period, it is essential to make the power of the peasantry absolute, it is essential not to allow others to criticise the peasant unions, it is essential to overthrow and trample underfoot the power of the “de-sheng.” Therefore all these actions spoken of as “going too far” have a revolutionary meaning in this second period.

In fact, it is essential to have a temporary reign of terror in the villages, otherwise it will not be possible to crush the activity of the counter-revolutionary parties there. It will be impossible to overthrow the “de-sheng.”

Contrary views impede the development of the peasant movement, they could undo the revolution. It is impossible for us not to be against them.

The “Riff-Raff” Movement

The right wing of the Kuomintang says: “The peasant movement is a movement of the peasant ‘riff-raff,’ it is a movement of the lazy peasants. This opinion particularly prevails in Changsha. When I travelled through the country, the gentry said:

“The peasant leagues can act, but it is necessary to change their leaders.

The gentry as well as the right wing of the Kuomintang say that the peasant movement must exist (as the peasant movement already exists and no one will attempt to say that it ought not to exist) but that the leaders of the movement must be changed. In speaking of the leaders of the lower organisation of the Peasant Leagues, they refer to them as the “riff-raff.” These are the people about whom they used to say that they are possessed of four of the greatest evils; then they were exploited but now they have raised their heads. Not only have they raised their heads; they have taken power into their hands. The Peasant Leagues have become sharp instruments in their hands. They tie their “de-shengs” with cords, put high hats on their heads and lead them through the villages (in the districts of Sianchu and Siansian this is known as “walking in a circle”; in the district of Tsyulin this is known as coming in crowds”). These gross acts reach the ears of the “de-shengs” daily.

The people who formerly stood above all are now classed as the lowest. That is why this is called “revolution.”

The Revolutionary Vanguard

We can regard any man or any object from two opposite points of views. As an example, we can take such conceptions as “very good” and “very bad”—as “riff-raff” and as the “revolutionary vanguard.

It has been stated above that the peasants have accomplished very great unprecedented revolutionary deeds; the peasants have done the most important work of the nationalist revolution. But did all peasants participate in that great revolution, in that vital revolutionary work? No.

The peasants are divided into three classes: the rich, the middle and poor peasants, and the attitude of the three classes to the revolution is not the same, just as their economic position is not the same.

During the first period the rich peasants (those who have a surplus of money or grain are classed as the rich) spoke only about the defeats in Kiangsi.

Chiang Kai Shek has been wounded in the leg; he took an aeroplane and flew to Kwantung”; “Wu Pei Fu has retaken Yuchow”; “The three democratic principles can never be realised because they have never been in force hitherto.”

The leaders of the Peasant Leagues (largely the “riff-raff”) showing their League lists would say: “Please join our League.”

The rich peasants would reply:

“Peasant Leagues! I have lived here many years; many years have I cultivated my land; and I never saw a Peasant League. Yet I was never hungry. Better forget about it!”

The best of the rich peasants would say:

“What kind of Peasant Leagues are you talking about? Is it a league for chopping off human heads? We must not hurt the people.”

And the “de-shengs” would say:

“It is very strange that the Peasant Leagues have been in existence only a few months; and already they have the audacity to stand up to the gentry.”

But when the Peasant Leagues began to lead the gentry who refused to discard their opium and pipe, through the streets, when they began to kill the richer gentry in the towns (for instance in the town of Anjun, Sianhu district, in the town Tanchi of the Nilsyain district), when the Society of the October Revolution, the anti-British League, and the victorious Northern Expedition Fraternity brought hundreds of thousands of people into the streets with large and small banners and iron spades on their shoulders, demonstrating their power, the rich peasants became frightened.

Victory–and Some Changes

The Northern Expedition scored one victory after another, rumours were now spread that Kiukiang was taken, that Wu Pei Fu was definitely smashed; they now displayed red posters with the inscriptions:

“Long live the three democratic principles!” “Long live the Peasant League!”

The rich peasants were in a frightful rage. “Long live the Peasant League” meant to them “Long live these people.”

The Peasant Leagues were jubilant; the members of the Leagues would say to the rich peasants. “Should we put you on our lists?”

“Within a month entrance fee will be ten dollars.” Under such circumstances, the rich peasants, gradually started to join the Peasant Leagues. Some of them paid 50 cents to a dollar entrance fee (originally the entrance fee was 100 coppers) but some of them were exempted from entrance fees altogether. Some of them, the “Die-hards,” have not joined the League as yet.

As the rich peasants were afraid to come to Leagues in person, they would send 60 or 70-year-old peasants to intercede for them.

The middle peasants (who have no surplus money and live on their harvest) hesitated. They had never thought of revolutionary organisations and were satisfied if they had enough rice and no one came to their doors to settle account with them. Originally, they had no ideas of their own, whatever. They would enquire:

“But will Peasant Leagues be organised?” “Will the three democratic principles be realised?” They were of the opinion that these things had nothing to do with the weather.

“Wili the leaders of the Peasant Leagues be able to forecast the weather?”

In the new period, the members of the Peasant Leagues would go to the middle class peasants with their lists and would say:

“Please join the Peasant League.”

The middle peasants would reply: “There is no hurry.”

In the second period, when the Peasant Leagues became stronger, the middle peasants began to join them. And although they behaved better in the Leagues than the rich peasants, they were nevertheless vacillating and unreliable.

The only ones who carried on the fight were the poor peasants. They fought from the time of their illegal existence down to the moment of open activities for their leagues. The organisations were their organisations; and the revolution became their revolution.

They alone fought against the gentry and against the “de-sheng. They were the ones who did all the destructive work.

They used to say to the right and middle peasants: “We have already joined the Peasant League, what are you hanging about the tail for “

The rich and middle peasants would reply smiling: “You have no roof to cover you, you have not even got a piece of ground to stand on, why should you not join the League?”

The poor peasants really had nothing to lose. They possessed nothing. It was a fact that they had no roof over their heads and no land to stand on.

And why should they not join the Leagues?

Poor Peasants in Control

From the report of the League of Changsha, we learn that 70 per cent. of the members are poor peasants, 20 per cent. middle peasants, and 10 per cent. rich peasants. The 70 per cent. poor peasants are sub-divided into those who possess nothing and those who have some property.

Among those who possess nothing are classed the people who have no occupation, no land, and no money, but who must either become soldiers, or find other employment or they are obliged to become tramps or bandits. They are one-fifth of the 70 per cent. of poor peasants.

Those who do have some possessions, have either a small strip of land or a little money; they work all their lives as artisans, till their own land, etc. They are half of the 70 per cent. (there are not as many poor peasants in other districts, but the difference is not great).

This mass of poor peasants constitutes the main support of the Peasant Leagues; they are the vanguard who break up the feudal regime, and do the work of the great revolution, which was unknown in the past.

Had there been no poor peasants (“riff-raff” according to the gentry), there would, of course, be no rural revolution and, of course, it would be impossible to overthrow the gentry and the “de-shengs” and to accomplish a democratic revolution.

As the poor peasants (particularly those who possess nothing) were extremely revolutionary, they took the leadership of the Peasant Leagues. In Chunchan the poorest peasants occupy 60 per cent. of all offices of the rural leagues; those who have some possessions hold 40 per cent. of the positions.

Some Blunders

The leadership of the poor peasants is extremely important. Had there been no poor peasants, there would be no revolution. To remove them from these positions would be tantamount to nullifying the revolution. To break them up would mean to destroy the revolution. Their revolutionary sentiment is not mistaken. They dealt the gentry and nobility a severe blow and now trample them under foot. They were guilty of many “excesses” during the revolutionary period, but those acts were a revolutionary necessity.

Some district governments, Party committees and Peasant Leagues to the south of Hunan made some blunders; they requested that soldiers be sent to defend the landlords and arrested the leaders of the lower peasant leagues.

In two districts, Chunshang and Tsiansian, some of the best members and the chairmen of the Leagues were put in prison. That was a very great mistake; such acts unconsciously support the reactionary party. When the leaders of the Peasant Leagues were arrested, the landlords rejoice; they know whether that is a mistake or not. We must combat the reactionary slogans of the “riff-raff” movement, and the movement of the “lazy peasants,” but at the same time we must not help the gentry and “de-shengs” to crush the leaders of the poor peasants.

Gambling and “Bad Men”

Although the leaders of the poor peasants were formerly “possessed of four evils,” they have now changed for the better. They themselves combat gambling and banditry: and in those places where the influence of the Peasant Leagues is great, gambling has disappeared and banditry has been eradicated. In many places there is no need any longer to lock one’s door at night.

A report from the Chunshang district says that of 100 Door peasant leaders, 85 changed for the better. The remaining 15 have not acquired any good attributes; they constitute a “bad minority”; the existence of a “had minority” of course, does not prove that what the gentry and “de-shengs” say about them is true. In connection with these “bad minorities,” there must be established a strict discipline in the Peasant Leagues which must be explained to them, but we must not send any soldiers, we must not undermine the confidence of the poor peasants, nor help the gentry and the “de-shengs.” That is what matters to us now.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-4/v04-n09-jun-15-1927-CI-grn-riaz.pdf