A report on the reversed situation of women in Ireland, who played such central roles in the pre-war labor movement and Revolution, and were now languishing under reaction in the new ‘Free State.’

‘Working Women in Ireland’ by Anne Curran from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 6 No. 15. February 25, 1926.

Ireland is an agricultural country. It is well to bear this in mind when dealing with the relationship of women towards the revolutionary movement in Ireland. The population of Ireland is approximately four and a half millions, equally divided between the sexes.

The classification of women engaged in earning their own living is as follows:

Professional (approximate): 28,000.

Domestic service: 144,918.

Industrial: 178,698.

Agriculture: 59,198.

Commercial: 9,747.

The professional section includes teachers, civil service, nurses and midwives. Domestic service includes the usual type of domestic workers. Agriculture deals with women employed on or around farms. Commercial includes working in offices. The Industrial section deals with women employed mainly in the large cities, such as Belfast, Dublin, Cork etc. There are 50,000 women workers employed in millinery, dressmaking and staymaking. Over thirty thousand are also employed in the manufacture of shirts and nearly thirteen thousand are employed in the various shops. There are many more engaged in undefined work, mainly those who have no fixed occupation. The above classification is sufficient to show the distribution of women workers in Irish industry.

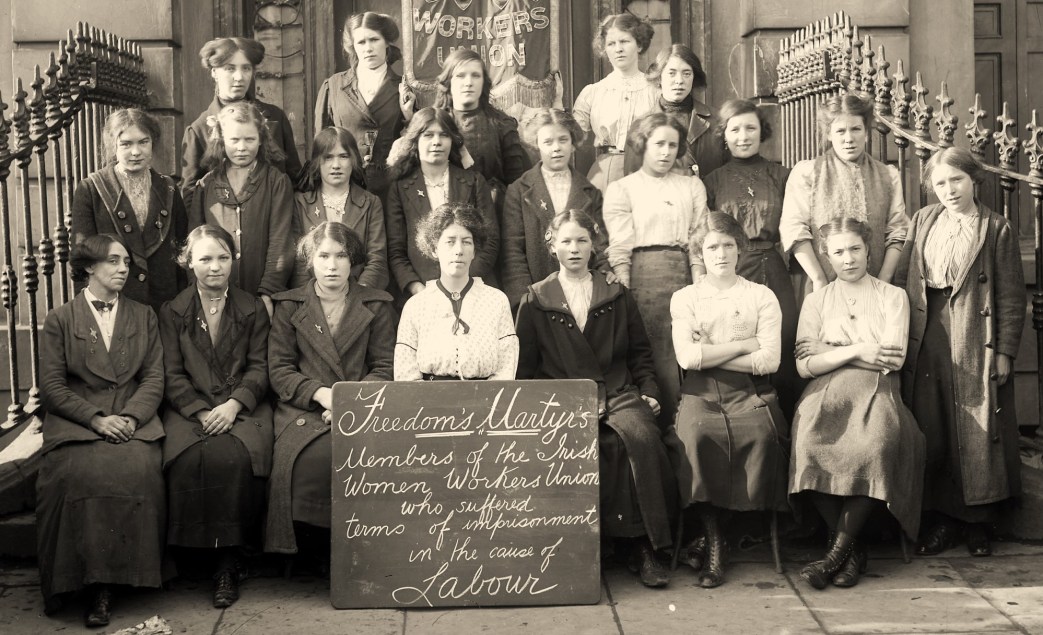

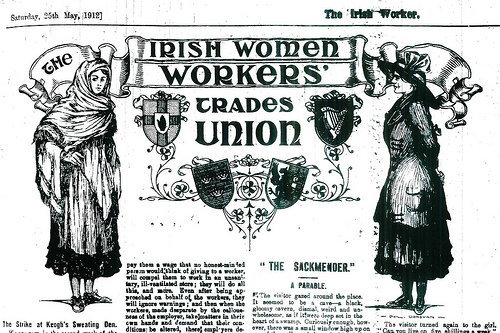

There is very little organisation among these women workers. In the pre-war days and during the war the women of the linen industry were fairly well organised, but the decline in this particular industry reflected itself in the women’s trade unions. There are 3,000 women organised in the Irish Women Workers’ Union. This organisation caters for all classes of women workers and is confined to the Irish Free State. It includes the Irish Nurses’ Union. There are two or three thousand women organised in the Irish Teachers’ Union and the Irish Union of Distributive Workers and Clerks. It is safe to say that there are not more than 10,000 organised women workers in Ireland.

The Irish Labour Party and Trade Union Congress, which is a combination of the political and industrial sections of the working class movement, has not made any real effort towards organising the women or even giving them an opportunity to take their real place in the movement. It is true that candidates have been run in local elections, but they have not been real working class women, rather of the pseudo-intellectual type, “educated” women so to speak. The leaders of the labour movement create the impression that their attitude towards women is purely one of lip-service and the feeling remains that they consider women more of a nuisance than an asset.

Women played a great part in the life of the Irish Labour movement. In the early days, 1911-13, in Belfast and Dublin women did good work in strikes. Their conditions of employment, especially in the city of Belfast, are very badly accentuated by serious unemployment. Prior to the war there was an agitation which led to an investigation of the conditions of employment of the women engaged in the linen industry. It was disclosed that women were embroidering over 300 dots on handkerchiefs and in return were paid the small sum of one penny. Some found that after a hard day’s work they were only able to earn sixpence. The conditions under which they worked found many of them victims of tuberculosis. In order that the flax might not get too dry and snap, steam is injected into the linen factories so that the heat is wellnigh unbearable, the result being that when the women step out into the cold atmosphere they soon, together with lack of real nourishment, contract tuberculosis. Some idea, of the housing conditions may be gained from the fact that despite the terrible conditions under which women worked, the chances of contracting tuberculosis were greater in the home than in the factory. An inquiry into the tuberculosis evil disclosed the following information:

“…the class of persons most attacked were housewives (280), the next in order being labourers (179), mill workers (162), children (117), warehouse workers (107), factory workers (59), and clerks. (54).”

There is a great deal of work done by women in their homes. A pre-war investigation brought out the terrible conditions under which these women worked. They worked from the early hours of the morning until late at night. Their wages were as follows: finishing one dozen shirts, sixpence; women s chemises, 7 ½ d. per dozen. These conditions, due to the war, were remedied a little, but unemployment following the conclusion of the war found these women workers drifting back to the old pre-war standards.

The lot of the woman engaged in agriculture is the lot of the “slave of slaves”. As has been humorously said, they have an eight-hour job twice a day. Their hours of labour are not regulated. They work from early morning until late at night. They rise before the animals and go to bed after the animals are asleep. In some cases marriage offers a little relief for some women, but to these women marriage means only the addition of caring for a family. It was because of these conditions that many emigrated to America and other places. Now that the immigration to America is restricted even that avenue of escape is closed to them.

These women workers’ have made no protest. They have been forever counselled to accept their lot without question. The Church plays its part in the subjection of these women. Any sign of protest or attempt to escape from the drudgery and aero of their existence meets with the strong opposition of the Church. Possibly the Church feels that if women engage in too much pleasure they might in time demand more time to play and less to work.

During the recent revolutions in Ireland women played an heroic part. Their deeds of heroism, in face of a brutal military power, did much to frustrate many of the plans of the British Government. Many times, under a hail of bullets, they stood and placarded their protests against imperialistic rule. They also took part in the actual fighting. It seemed as if the oppression of the years had at last flared into revolt as these women were so passionately devoted to the ideals of the revolution. Home ties were smashed, friendship broken, when these women sallied forth to smash the power that held the country in subjection. It is to be regretted that the movement that produced such women has only created an organisation of women who lack the necessary political intelligence to translate their heroic spirit into a well-organised political and industrial campaign against the powers-that-be. The leadership of these women, organised in the Irish Republican movement, is deplorably weak. It engages in negative attacks on the government but fails to understand that political freedom is but the outside shell with economic freedom the kernel. Republican women like Mary MacSwiney even go out of their way to laud Mussolini, thus finding a common ground with the ruling class of Ireland. This state of affairs will not last forever. Already there is a growing move within the ranks of the Irish Republicans for a more concrete programme and less flowery speeches.

The future of the working of Ireland is one that offers much promise. Within the immediate future a Workers’ and Peasants’ Party will be organised under the leadership of Comrade James Larkin. This party will make a direct appeal to the women, not alone to those engaged direct in industry, but to housewives and domestics. The women of Ireland will be given their place in the sun and in the unity of the sexes there will be created a virile labour movement.

International Women’s Day will not mean much to the Irish women in these days. That is to be regretted, but out of the chaos and uncertainty of to-day there will come a movement that will find the women of Ireland marching beneath the banner of the Communist International and celebrating International Women’s Day with the women workers of the world.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. The ECCI also published the glossy magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 monthly in German, French, Russian, and English. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1926/v06n15-feb-25-1926-Inprecor.pdf