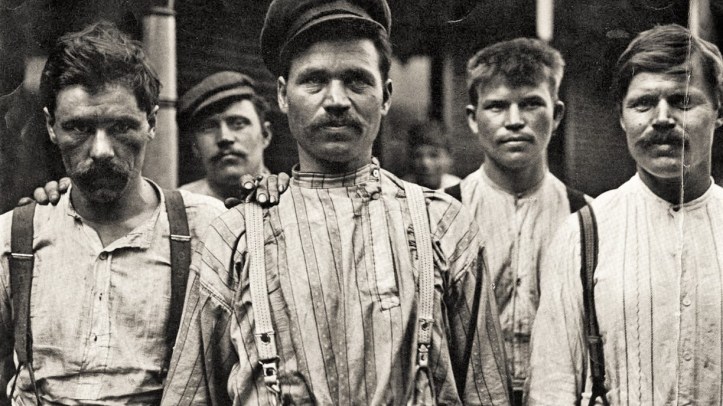

The capitalists’ imported a labor commodity, derisively called ‘hunkies’ (later morphing into the epithet ‘honky’), Eastern European workers, for the steel mills of western Pennsylvania whose lives were non-nonchalantly dismissed by both bosses and labor ‘leaders.’

“Only Hunkies” by Louis Duchez from Solidarity. Vol. 1 No. 39. September 10, 1910.

Hunkeytown belonged to the Steel Trust. For years the slaves of its mills were quiet and submissive. Long, dreary hours of toil and starvation wages–that was their lot. The increasing profits of the Steel Trust meant nothing to their miserable lives–nothing but fewer jobs and often lower wages.

But there was a limit to their endurance. Mass feeling grew; the spirit of revolt gripped the lives of the 3,000 slaves of that great concern. The sleeping giant–LABOR–awoke, rubbed its eyes, and arose.

One morning in early spring the entire scene changed. As usual, each of the 3,000 men and boys employed in the great mills went to work. At the gates of the plant they gathered. All was silent, save the whispering mumbling voices occasionally heard in the various groups of that vast assemblage.

Ten different tongues were represented, yet it seemed that every one knew the reason for this gathering: understood why on this particular morning each man and boy did not pass through the gate and punch the clock, which registered whether he, was on time or not.

“What does all this mean?” thundered the superintendent of the mills in arrogant tones.

The committee representing the 3,000 men, standing at the main entrance, replied: “Two dollars a day; eight hours; or no work.”

This stirred the ire of the head of the mill; he was dumfounded at such action. He said: “Are you men crazy?”

“Two dollars a day; eight hours; or no work!” The committee knew they had the mass behind them and they did not argue with the superintendent. And in the face of his abuse they stood indifferent–but determined.

Realizing they could not be bluffed, he rushed into the mill office, telephoned to the city police and the sheriff and ordered cops and deputies at once.

Three hours later they came, five, hundred of them and armed to the teeth. Seeing this the mill men passed on in through the gate and took their places as if nothing out of the ordinary had happened. The Steel Trust bosses were relieved: the slaves have been bluffed out, they thought.

But the next morning the same thing happened. The men gathered at the same place everyone of them, with their dinner pails with them. And the committee was in its place and made the same demands as the morning previous. This was something new to the superintendent. He became more arrogant than ever. The cops and deputies were again ordered. They came–and the men passed on in as they had done the morning before.

Three days in succession the mill men did the same thing. They stood at the gates en masse and made their demands. Company “bulls” tried to get them to talk, but the “bulls” were told that they had a committee to present their grievances and make demands for them.

The next morning the superintendent, realizing that he was up against something that he had never met before, asked the governor for the militia. They came during the night, and were in camp at the gates of the mill when the men arrived.

Without a word of instructions, apparently, each man passed on into the mill without stopping as the gates. Work went on in the plant as it had gone on for years before. The hours were still long, and the wages poor.

For two weeks the militia stayed in Hunkeytown and camped at the gates of the steel mills. And for two weeks the men in the mills went to work as usual.

“We have them bluffed for good this time,” said the superintendent to his associates. “They needed this lesson. Damn them, if they open their mouths we’ll shoot them down like dogs.”

But it cost the Steel Trust 85,000 a day to keep the militia and its own increased force of police at the mills. And appeals by the thousands were sent to the governor to take away the soldiers. Preachers howled that the soldiers were drunkards and that they were “ruining” the girls of the town.

The soldiers packed up and went. The next morning the 3,000 men again gather at the gates of the mill, and again made the same demands.

And they won. The bosses of the Steel Trust learned that they had men to deal with that would stick together. They recognized power and solidarity.

And this is the way the “hunkies” beat the Steel Trust and won its “recognition” and respect.

The most widely read of I.W.W. newspapers, Solidarity was published by the Industrial Workers of the World from 1909 until 1917. First produced in New Castle, Pennsylvania, and born during the McKees Rocks strike, Solidarity later moved to Cleveland, Ohio until 1917 then spent its last months in Chicago. With a circulation of around 12,000 and a readership many times that, Solidarity was instrumental in defining the Wobbly world-view at the height of their influence in the working class. It was edited over its life by A.M. Stirton, H.A. Goff, Ben H. Williams, Ralph Chaplin who also provided much of the paper’s color, and others. Like nearly all the left press it fell victim to federal repression in 1917.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/solidarity-iww/1909-1910/v01n39-sep-10-1910-Solidarity-San-Diego.pdf