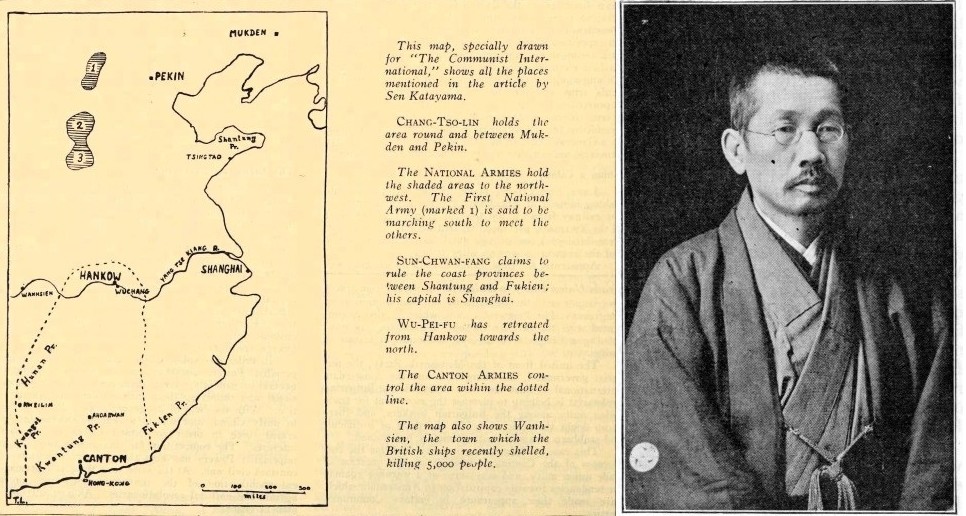

Sen Katayama on the consequences of the Koumintang’s First Northern Expedition in 1926.

‘The World Conflict in China’ by Sen Katayama from Communist International. Vol. 3 No. 1. October 15, 1926.

THE Canton expedition against the North has so far been successful. The expeditionary force has captured Wuchang and Hankow.

But this will not as yet prove to be a decisive victory for the Canton army, as it will have to look after its rear and flanks before making any further advance.

Chen-Chiung-ming is trying to get a chance to attack Canton from Fukien province, while Sun-Chwan-fang’s position remains one of hostile waiting. A firm grip on the province of Hunan is certain to strengthen the influence of the Canton government in South China. And if only the Canton expeditionary force under General Chiang-Kai-shek avoids making a hasty advance without first consolidating its base of operations, and above all keeps Canton and the Kwantung province safe from any attack by Chen-Chiung-ming, the Canton army is sure to reap the full fruits of its victory.

Although an expedition against the North has often been discussed by the Canton Government, it has never hitherto come to anything. When Sun-Yat-sen was President of the Canton Government in 1922, he attempted an expedition to the North, establishing his headquarters at Kweilin, in Kwangsi province, but one of his generals, Li-Lieh-chun, opposed the plan. When General Chen-Chiung-ming, then Commander-in-Chief of Sun-Yat-sen’s army and now one of Canton’s opponents, disappeared and resigned, discontent spread through the army. Chen seized Canton, and Sun-Yat-sen had to flee for his life. Another unsuccessful attempt was made by a General Tan-Yen-kai, the former war lord of Hunan province, and another of Sun’s one-time subordinates.

China a Colony

Later Sun-Yat-sen made another attempt, establishing himself at Ahoakwan, the northern terminus of the railway from Canton towards Hankow in the north of the Kwantung province, but that was all. A few shots were fired and one or two small skirmishes occurred, but the expedition was an utter failure.

Apparently, the time for the expedition has been well chosen. The First National Army, although it has retreated, has remained quite intact, and is spoken of with admiration even by its enemies; and the Second National Army, though also defeated, is now reported to be well organised and ready at any moment to strike. But it has proved to be impossible for either of these two armies co-support the Cantonese, as their bases are too far north.

Sun-Chwan-fang at Shanghai holds the key to the situation just at present. We do not know what he means to do. Lake all the other generals in China (excepting those of the Canton Government and People’s Armies) he has no freedom of choice; he must move according to the wishes of his foreign imperialist supporters. A correct estimation of each foreign imperialist Power and its influence is absolutely necessary if we want to judge the situation in China correctly.

China is an international capitalist colony, a dumping ground for the goods of capitalist countries. In order to keep her as a profitable market, the imperialist countries are struggling to keep her under their control. By dumping cheap goods from the industrially advanced countries into China, they make it impossible for her to start her own industries to supply her home market. In order to crush China’s industries the imperialists use the “unequal treaties” which deprive China of economic freedom.

Moreover, the foreign capitalist powers are destroying the old home industries. The handicraft men, in debt, lose their tools and soon are unemployed; the peasant proprietors lose their land and also became unemployed or dispossessed—inevitable consequences of the industrial revolution in China.

The Industrial Revolution

An industrial revolution due to the inroads of foreign capital always causes misery and unemployment, but in China poverty and misery are more terrible than in any other country. The industrial revolution in China is not like what it was in England or even in Japan. Both countries were able to re-employ in their developing industries those who were thrown out of work by the change in industrial methods. In China the unfair and oppressive treaties imposed by the foreign capitalist Powers make it impossible to build up new industries in place of the old-fashioned handicraft industries. Furthermore, China’s restricted income from the customs duties and salt tax is robbed from her by her foreign creditors.

In order to exploit China each of the foreign imperialist Powers supports one or another militarist general or generals, giving them cash (for rich concessions) and supplying them with artillery and ammunition. With the help of its generals, each Power hopes to unify China, and set up a central government by armed force in order to exploit China in its own interests. The competition for this among the foreign imperialist Powers has kept the country in a state of constant civil war. At the same time there is a permanent mobilisation of the counter-revolutionary forces against the national revolutionaries. As a result—permanent chaos.

Workers and Nationalism

All this brings the handicraftsmen to increasing ruin, and the middle classes lose their economic independence. The number of unemployed and paupers among the handicraftsmen and middle classes is continually increasing. The direct result is an enormous increase in the number of mercenary soldiers, bandits, prostitutes and beggars. It is estimated by the highest authority in China that there are some thirty million paupers. A mere sign put up at a factory gate, “Workers wanted,” will usually collect five or six times more people than is needed. A cotton factory announced it needed working girls, and within two hours, two thousand had arrived. The number needed was only three hundred.

The fact that the great Chinese factories are under foreign control, gives every labour dispute or strike the tone and feeling of the nationalist movement. But this struggle does not fall into narrow nationalism; the Chinese workers, the poor peasants and coolies have grown to be a people entirely dispossessed of nationality by their traditions and environment. The Chinese governments of the past have never show any sign of wanting to help or protect the lower classes. To the Chinese officials and bureaucrats the workers and the poor peasants are only objects of exploitation, nothing else. The bureaucrats and the rulers are all exploiters, oppressors of the masses; and the intelligentsia have also co-operated with the bureaucrats in exploitation. Thus the workers as well as the ruling class dislike the intelligentsia: it was only an incident, or rather the influence of the “Zeit-geist” that the workers came out to support the demonstration on May 4, 19109, against the Peace Treaty. (The Treaty of Versailles gave Shangtung province and Tsingtao to Japan.) The support of the workers gave a decisive victory to the movement. The Pekin students started: these anti-Japanese demonstrations, and also the movement against the Chinese diplomats who signed the Treaty. This took the form of a student’s strike lasting a month, and obtained support from the Pekin merchants, who closed their shops for a week. But until the workers came out on strike the movement did not achieve a complete victory. The non-nationalist mood of the Chinese masses has developed into a sort of primitive Communism. The self-governing guilds of handicraftsmen and traders are strong. Among the lower masses these organisations have acquired in many cases very great strength and stability; all disputes and quarrels are settled within them, and they even administer death sentences. The secret societies have become a nation; within them the most rigid discipline prevails. Local organisations are federated according to the provinces.

These guilds have played and still play a big role in the people’s economic life. They should be very carefully and extensively studied, in order to understand properly the economic and social life of China.

Remember the solidarity and compactness of the labour unions, and more particularly their strength in the Shanghai general strike, which developed into a national movement. The solidarity of the workers in unions formed very recently cannot be understood unless the antecedent life of the workers themselves is made clear. The Chinese workers, down to the coolies, are accustomed to secret organisational work, and have formed by long usage and custom an ineradicable habit of obedience to their organisation. This makes them very good and capable union members during strikes or persecution by the exploiters. They have been taught to be ready to make the greatest possible sacrifices for their organisation. They obey eagerly, even at the cost of their lives. They are trained in underground work, and government oppression and persecution does not make them timid or discouraged at all. For them there is no authority or State but their own organisations, which are the nation and the government to them.

There is another fact that we must not ignore, if we want to understand life and conditions in China. That is the village militia and “citizen army” organisation. Each village is usually enclosed by walls. The village forms a long street, and at each end of the street there are iron gates that can be closed to prevent attacks by bandits. Each village has its militia, armed more or less effectively, to protect it from bandits. The city merchants have also their own militia, organised by themselves to protect the city.

Ripe for Revolution

The guild system in some places is still in full force. But it is rapidly being destroyed by the influx of foreign goods as the transport system develops. The unemployed handicraftsmen and middle class peasants in many cases become bandits, soldiers, thieves, vagabonds, prostitutes and beggars; these are a menace to the peaceful people in the farms, villages and towns. The destructive work of the industrial revolution is felt keenly throughout China. Among the masses discontent is growing, and they are awakening to a new life.

The Chinese masses, living in general chaos and disturbance, are ripe for the revolutionary movement everywhere. Irrespective of the immediate outcome of the militarists’ struggles or the outcome of the Canton expedition, China’s revolutionary movement will go forward.

What is most needed in China to-day is the organisation and unification of the revolutionary forces. The Labour movement is comparatively young, and not at all well organised on a national scale. The Communist Party is very young and inexperienced.

China will inevitably become the very centre of the world conflict between capitalism and Communism. Capitalism is represented there by the imperialist countries, Communism, of course, by the Soviet Union. The militarist generals will be utilised by the foreign imperialists, more and more, to crush the revolutionary movement, including the Labour and peasant unions. To counteract the combined attacks by the imperialists and the native reactionary generals, we must consolidate the revolutionary forces. The present chaotic warfare will also continue until the revolutionary forces become strong enough to annihilate the reactionary militarists, and establish a stable revolutionary government, based on a strengthened Kuomintang Party and defended by re-organised National Armies, combined with the Canton Red Army into one strong revolutionary fighting force.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-3/v03-n01-oct-15-1926-CI-grn-riaz.pdf