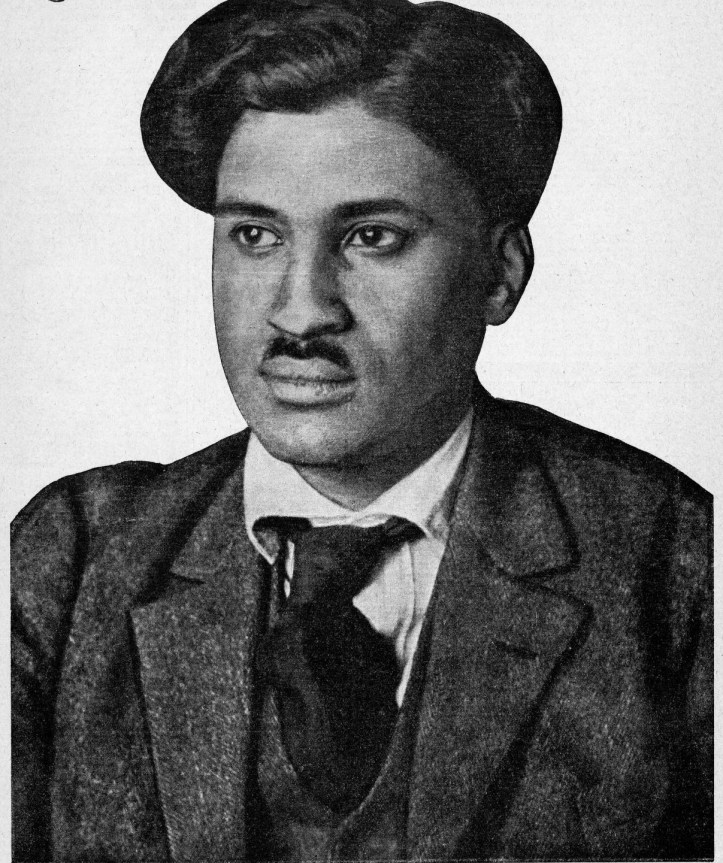

A fantastic essay in which Roy describes the British Labour Party as ‘neo-Liberal’ in 1928, examining the political and social roots of the party for which Keir Starmer was a natural to lead.

‘The Metamorphosis of the British Labor Party’ by M.N. Roy from The Communist. Vol. 8 No. 1. January-February, 1929.

The policy of a bloc with the Liberals in the coming general election as advocated by the extreme right wing, led by Philip Snowden and desired by a considerable section of the Liberal Party, has been rejected formally by the British Labor Party. None but the most naive Labor enthusiasts believe that in the next election the Labor Party will be returned with such an enlarged number as will give it a parliamentary majority required to form an independent government. Nevertheless, the leaders of the party confidently prepare themselves for office, and this being the case, the resolution of the Birmingham Conference is by no means a repudiation of the policy of coalition; for, under given conditions, the next “Labor Government” cannot be anything different from that of 1924—Labor in name, coalition in fact. Indeed, the possibility of an open Labor-Liberal Coalition Government is not altogether excluded by the refusal to form an election bloc. The result of the election will be the decisive factor in determining the tactics of the Labor Party.

Considering its tacit readiness to form a coalition government and the complete right swing of its general policy, the insistence of the Labor Party not to enter an electoral bloc with the Liberals becomes somewhat paradoxical. By this insistence it might drive the Liberals into a bloc with the Conservatives. As a matter of fact, such an anti-labor bloc has already been formed in a number of constituencies. This election agreement might develop into a government by a bourgeois bloc after the election. The leaders of the Labor Party must have taken this possibility into consideration before deciding to contest the coming election independently. Evidently their decision has been influenced by the consideration of other possibilities. Besides, the Labor Party will contest the coming elections not in coalition with the Liberals, but as the exponents of true liberalism. This is the key to the situation.

The following are the other considerations that evidently have influenced the determination of the electoral policy of the Labor Party. First, there is a possibility of a split in the Conservative Party on the question of protection. On the other hand, open coalition with the conservatives is very likely to hasten the decomposition of the already depleted liberal forces, in which case the left wing will join the Labor Party as some of its most advanced members have already done.

As a result of this likely dual-split, the bourgeois bloc in the new parliament will be without a substantial majority, if the labor forces are fairly increased in the next election, as they are sure to be. Thus, after all, a minority Labor government might again be the way out of the parliamentary crisis as it was in 1924. Second, an electoral bloc and then a governmental coalition with the conservatives will so discredit the Liberal Party that it will wipe out the political scene. Not particularly anxious to commit suicide, the liberals are not very likely to follow up the electoral bloc by entering a coalition government with the conservatives. So, in view of the certainty that more Labor candidates will be returned in the coming election, there again is the chance of Labor getting into office, owing to the inability of the bourgeois parties to unite or to command a working majority separately.

Thus, in any case, the chance of the Labor Party getting into office is not seriously prejudiced by the rejection of the policy of an electoral bloc with the liberals. And, in either case, in office or in opposition, the Labor Party will make a considerable advance towards its goal, namely, to take the place of the defunct Liberal Party and hold high its traditions of bourgeois radicalism. When this goal is realized, the Labor Party will be in a position to have a parliamentary majority, not representing the working class, but on the strength of having captured the votes that, today, are cast for the Liberal Party. The Labor Party refuses to make an electoral bloc with the liberals, because it wants itself to be the Liberal Party. Its new program and the Birmingham Conference have removed any doubt that might have been there as regards the direction of development of the Labor Party. The leaders of the Labor Party are well acquainted with the British Constitution and how it works. They know that under the given electoral system the Labor Party can never have a majority in the parliament by only counting upon the working class vote. So, they must angle for the vote of others, and the Labor Party must undergo a process of metamorphosis in order to win the confidence of and conciliate these latter. The coalition and bloc are taking place but not between the Labor Party and the Liberal Party. The process is much more deep-seated. It is taking place inside the Labor Party. The social basis of the Labor Party is changing. From the party of the working class, it is becoming the party of the liberal bourgeoisie plus the working class. This was what the Liberal Party was in the hey-days of Gladstonianism.

It is not correct to characterize the British Labor Party as a Social Democratic Party. It has never been one, nor is it developing into one. In its fight against Communism it adopts certain organizational features of the Social Democratic Party. But in stark opposition to the majority of its social composition (which is working class), ideologically and politically it has become a party of the liberal bourgeoisie. The traditions of Victorian radicalism, which for a considerable time hindered the birth of the Labor Party, and then essentially influenced its growth, has reasserted itself, as it were, with vengeance, in the new program of the Labor Party.

Apart from other considerations indicated above, the fear for the revolt of the masses does not allow the leaders of the Labor Party to enter into an organizational understanding with the Liberal Party, as a party. (The understanding with the social elements represented by this party is maturing every day.) But the new program testifies to complete harmony ideologically. Indeed, MacDonald & Co. gleefully greet the eclipse of the Liberal Party, and proudly present themselves before the “bereaved Nation” as the new standard-bearers of true liberalism. (This is actually stated in so many words in the new program, and repeated on innumerable occasions!) That is, what has happened is much worse than a Labor-Liberal electoral bloc or governmental coalition. The Labor Party is transformed into a neo-Liberal Party.

Although a working class party by social composition, the British Labor Party never committed itself fully and frankly to Socialism or accented Marxism for its guiding principles, as all the Social Democratic Parties of the Continent did in the earliest stages of their existence. Indeed, Fabianism, which constituted the ideological foundation of the Labor Party, developed as a negation of the basic principles of Marxism. Ambiguity has all along been the main feature of the program of the British Labor Party, and its social orientation always super-class. But whatever doubt there might have been as regards the tendencies of the Labor Party, has now been definitely removed. The new program of the Labor Party, which is significantly titled “Labor and the Nation,” is free from all Socialist blemish, except in meaningless phrases used in peroration and with an eye to the galleries. It is admittedly not a program of the working class. According to this document, the Labor Party “speaks, not as the agent of this class or that” and reassures the Nation against the “bogey of Socialism.” The new program is a plan of how the Labor Party in office will administer the affairs of the nation and of the empire, both of which, it says, have been driven to the verge of ruin by the mismanagement of the present government.

In the new program, Socialism has been substituted by a scheme of “enlightened” capitalism which admits reformist social legislation. To deceive the working class it is actually stated in the program that the liberals have adopted a Socialist policy! The reverse, of course, is the true picture of the situation. The Labor Party has adopted the principles and program of bourgeois radicalism, and seeks to pass them on as “Socialist policy.” It is further admitted in the program that “some among the principles for which labor has long stood are endorsed by the Liberals.” The author of the program, Mr. MacDonald and his colleagues find this triumph of theirs “gratifying to observe.” Here again, of course, the reverse is the truth. But provided that it is so, then, there must have been something seriously amiss with “those principles,” if they could be accepted by the bourgeoisie. In any case, the evidence adduced to prove the success of the policy, shows that it could not have been a policy defending the interests of the working class.

The fact, that the “principles for which the British Labor Party has stood” ever since its birth are as much Socialistic as can be endorsed by Lloyd George, explains how a great working class party can so completely degenerate into bourgeois liberalism. The causes of the present degeneration of the British Labor Party are to be found in the history of its birth and growth, and the conditions under which it was born and thrived. Proletarian thinkers of Britain contributed much to the pre-Marxian theories of Socialism. The experience of the British proletariat is a bitter experience of fierce class-struggle. Nevertheless, the modern labor movement in no other European country was so much corrupted by bourgeois liberalism as in Britain. History explains this paradox.

The collapse of the Chartist revolt was followed by a prolonged period of depression in the British labor movement. That depression coincided with continuous prosperity of capitalism. Taking advantage of these twin factors the bourgeoisie succeeded in permeating the upper strata of the working class with the belief in political democracy, economic liberalism and social reform. While in most of the continental countries the proletariat remained largely deprived of the rights of citizenship, political democracy forged ahead in Britain. All the adult male members of the working class were enfranchised by the Reforms Act of 1867. In the ‘seventies the Liberal regime introduced a whole series of progressive social legislations which were hailed by the working class as the realization of the Chartist program. Fabulous accumulation of capital in consequence of gigantic development of industries at home, monopoly of the world trade and plunder of the colonies, enabled the British bourgeoisie to create a labor aristocracy completely wedded to Gladstonian liberalism, and hostile to the Socialist propaganda of class-struggle. Under the leadership of that corrupt labor aristocracy, the working class discountenanced politics, leaving the Parliamentary Committee of the Trade Union Congress to act as an agency of the Liberal Party.

In the eighties, Gladstone was the most popular man among the British workers. He had a very keen eye on organized labor, and was successful in tying it to the apron-strings of his liberalism. For the time being he did prevent organized labor in Britain from moving in the direction of the class-struggle and Socialism. What could not be accomplished on the continent by violent and coercive measures, was done in Britain by Gladstonian liberalism. While, for example, in spite of the anti-Socialist law of Bismark, Socialism found a firm rooting among the German proletariat, the labor movement in Britain generally kept clear of the Socialist path, thanks to Gladstonian liberalism. Revolutionary workingmen and intellectuals, exiled from the continental countries, found asylum in Britain; but their propaganda, which influenced the labor movement on the continent, in spite of all obstacles, failed to make any lasting impression upon the working class in the “land of freedom.” In those days, Socialism was combatted in Britain not by persecution, as on the continent, but by political bribery and ideological corruption. Incipient Socialists and prominent trade union leaders were often raised to places of “honor and distinction” in Britain. In 1834, the anarcho-communist thinker and writer, William Goodwin, was made a “Gentleman Usher” of the Royal Palace. Samuel Bamford, a working man who took a leading part in the Peterloo demonstration, was given a Court appointment in 1849. Later, Gladstone admitted into his cabinet trade union leaders for meritorious services rendered to liberalism. In 1886, Henry Broadhurst became an under-secretary of state. The process of bribery and corruption culminated in the veteran labor leader John Burns becoming a member of the liberal cabinet of Campbell-Bannerman in 1906.

The pernicious effect of this policy of bribery and corruption could not last forever; but it did influence the British labor movement so profoundly as to distort its subsequent development. For example, even today, when the British bourgeoisie have completely discarded the mask of liberalism (the economic foundation having been eliminated), and the working class is slowly but steadily moving in the unavoidable path of revolution, when class-war rages in fierce nakedness throughout the country, we find J.H. Thomas eulogizing the political institutions of Britain, under which he could “become a cabinet minister from a humble engine-cleaner.”

In course of time, the factors that enabled the British bourgeoisie to bribe the thin stratum of labor aristocracy, and through it corrupt the entire labor movement ideologically, began to lose their force. Britain’s monopoly of the world market was threatened by the growth of industry in other countries. The successful competition of the American and German industries thriving behind tariff walls, caused doubt about the doctrine of free trade. In the middle of the eighties there began a serious depression of trade. In spite of the trade union leaders, who still believed in liberalism and opposed Socialism, class-struggles began to develop. Great strikes took place. In 1887, there were nearly a million workers unemployed. Liberalism had not given the working class anything more substantial than formal political rights, and a glowing promise of heaven on earth as regards economic and social conditions. The promise remained still a promise unfulfilled. Dissatisfaction grew everywhere. Finally there was demand for “independent labor politics.”

The propaganda of Marxian Socialism had begun in Britain with the foundation of the Social Democratic Federation in 1881. But it had not made any headway. In the Trade Union Congress of 1887 Keir Hardie openly condemned the liberalism of the labor leaders, and proposed that labor should be independently represented in parliament. Thus began the process of freeing the working class from the influence and control of the bourgeoisie. But what Keir Hardie and his followers desired was mere organizational freedom. The attempt to break the much stronger and more harmful ideological bondage was still to be made, and the success of the attempt was a very far cry. The conditions favorable for the attempt were maturing. Despite the corrupt trade union leaders, Socialist propaganda, carried on by small bodies of advanced workers and de-classed intellectuals, slowly but steadily penetrated the proletarian ranks. Liberalism had signally failed to give anything to the working class. Unemployment became a permanent feature of social conditions. Strikes were frequently taking place to defend the interests of the workers. Flouting openly the doctrines of Mill, which had previously blinded the working class by their glamor, the bourgeoisie ruthlessly crushed the efforts of the workers to improve their conditions. Even the Trade Union Acts of the ’seventies, which had so thoroughly won organized labor for liberalism, were attacked.

Such an atmosphere of maturing class-struggle, naturally, was favorable to the growth of organizations having for their object the liberation of labor from liberalism, and the inauguration of independent labor politics, which, if anything, could only be the struggle of the proletariat for Socialism. Indeed, all the organizations advocating independent labor politics were under Socialist leadership, and more or less committed to the program of Marxian Socialism. It was at that juncture that the Fabian Society came into existence. While the modern labor movement in Britain was showing the first signs of class-consciousness, and beginning the striving towards the path of Socialism, there appeared on the scene a group of bourgeois intellectuals with doctrines of pseudo-socialism. The objective role of the Fabian Society was to divert the British working class from the revolutionary way. Its doctrines were a representation of the exploded principles of bourgeois social reform, dressed up in socialist garb. Class antagonism had developed to such a pitch that the more advanced sections of the proletariat could no longer be kept away from Socialism with the deceptive lure of liberalism. So, a fraudulent version of Socialism was created. Fabianism was nothing but liberalism reborn.

The aims of the Fabian Society as stated in its report to the International Socialist and Trade Union Congress held in London in 1896, was “to persuade the nation to make its political constitution thoroughly democratic, and so to socialize its industries to make the livelihood of the people entirely independent of the capitalist.” Admittedly, the Fabian Society was not a working class organization. It did not recognize the basic fact that capitalist society is divided into antagonistic classes. It directed its appeals “to the men and women of all classes who saw the evils of society and desired to remedy them.” These sentences written thirty-two years ago laid the ideological foundation of the British Labor Party which was subsequently formed. The Labor Party never freed itself from the Fabian Social reformist outlook. The liberal social reformist ideology, with which it came into existence, is the key-note of the new program of today. Strictly speaking one cannot accuse the British Labor Party of having betrayed Socialism; it never really accepted Socialism. The new program makes this clear. It is the “return of the native” to the pristine purity of his spiritual home.

Indeed, the ideological foundation of the British Labor Party was laid by those whose declared mission was to refute the revolutionary theories of Karl Marx. The ideologist and founder of the Fabian Society, Sidney Webb, was the first “socialist” who set himself the task of revising the epoch-making findings of Karl Marx. So, the British Labor Party was not corrupted by revisionism. It was born under the shadow of revisionism. This is the fundamental difference between it and the Social Democratic Parties of the continent. Sidney Webb, assisted by Bernard Shaw, pointed out the political changes that had taken place in Britain since the enactment of the Reform Bill of 1867, to prove that Marxian theories of class struggle and revolution were not applicable to the new situation. Whig individualism had given way to the liberal doctrines of collectivism and social reform. This together with the political rights and economic gains made by the working class, in the opinion of the Fabian ideologists, refuted the theory of irreconcilable class antagonism, and eliminated the necessity of revolution. They argued that theories constructed on the basis of conditions prevailing in pre-democratic days, could not be applicable in a democratic country where the state had undertaken the task of social reform. An examination of the basic principles of Fabianism does not leave room for any doubt as regards its historic role which was to revive decayed bourgeois liberalism with a fraudulent new label—that of Socialism. Just when the bourgeoisie were discarding the philosophical radicalism of Bentham and political liberalism of Mill, the Fabians began their futile fight against the Marxian theories of class struggle and revolution precisely with these discredited and discarded weapons. Admittedly, Sidney Webb was an opponent of Marx. But he was not even a progeny of pre-Marxian British Socialists. He was the disciple of John Stuart Mill, and spiritual grand-child of Jeremiah Bentham. His mission was to smuggle into the working class movement the capitalist doctrine of utilitarianism with the fraudulent label of Socialism. Webb continued the services of Mill to the bourgeoisie—to construct a comprehensive system of the collectivist theory of social reform, as against the unrestricted individualism of the days of primitive accumulation, which would take off the unbearably sharp edges of capitalist exploitation, and lull the proletariat into a deceptive conception of bourgeois democracy.

The Fabians not only rejected the Marxian theories of class struggle and revolution; their “Socialism,” which the British Labor Party eventually accepted under the pressure of the masses, even did not countenance the abolition of the wage system. It was, of course, logical that the wage system cannot be abolished, so long as society remains split up into classes. Fabian Socialism “by no means involved abolition of wages.”1 The Fabians also maintained that the demand that the workers should be the owners of the whole product of their labor, was impractical. In view of these fundamental principles of their theoretical system, the “socialization” of industries advocated by the Fabians essentially did not imply anything more radical than state or municipal administration. This was an elaboration of the collectivist theory of state evolved by bourgeois political philosophers upon the breakdown of unrestricted individualism. Indeed in the program of the Fabian Society it is stated that it “aims at the reorganization of society by the emancipation of land and industrial capital from individual and class ownership.” The attainment of this aim will be the transformation of the bourgeois democratic state into a huge, all-absorbing, monopolist capitalist trust. For the democratic state is the corner-stone upon which the Fabian Socialist castle will be built. Granted that the aim is the abolition of capitalist exploitation and overthrow of the bourgeois state, it can never be realized by the methods recommended. It is taken for granted by the Fabians that everybody is interested in the social transformation pleaded by them, or can be persuaded to be interested. With this supposition belied innumerable times before and since their theories were constructed, the Fabians emasculated Socialism by disassociating it from the class struggle, and the revolutionary overthrow of the capitalist state.

The assertion in the new program of the Labor Party that a section of the British bourgeoisie has adopted “some of the principles for which labor has long stood,” and the reiteration in the same document that the Labor Party would attain its goal “by peaceful means, without disorder or confusion, with the consent of the majority of the electors and by the use of the ordinary machinery of democratic government,” are in strict conformity with the neoliberal ideology with which the Labor Party was born. These are a re-vindication of the Fabian anti-socialist theories.

* * * *

The events leading up to the formation of the Labor Party were marked by a struggle between revolutionary Socialism and camouflaged liberalism for the ideological control of the nascent organization. The revolt of Keir Hardie culminated in the foundation of the Independent Labor Party in 1893. Nearly all of the 120 delegates present at the inaugural conference professed Socialism; but the declared object of the new party was not to propagate “doctrinaire socialism,” but to promote the formation of an independent political party of the working class. In 1900 a conference, representing over half a million organized workers, was held in London as a result of the activities of the Independent Labor Party. The conference decided to put up independent labor candidates in the parliamentary elections, and set up the Labor Representation Committee to enlist the sympathy and support of organized labor for the new movement, Three years later the Labor Representation Committee assumed the name of Labor Party. It should be noted that the characteristic feature of that first period of organizing activities was the discount placed upon Socialist propaganda even by those who called themselves Socialists.

The debate in the London Conference over the aim of the prospective Labor Party was very significant. It indicated that even the so-called “advanced men” headed by Keir Hardie, advocated but organizational separation of labor from the bourgeois Liberal Party. They were not yet free from the traditions of liberalism, under the dark shadow of which the Labor Party came into existence.2 The conference rejected the old policy of collaboration with the liberals. John Burns defended the old policy. Disgusted by the atmosphere of the conference he exclaimed:

“I am getting tired of working class boots, working class trains, working class houses and working class margarine. We should not be prisoners to class prejudice, but should consider parties and policies apart from all class organization.”

John Burns was defeated in the London Conference; but his spirit lived through the years of storm and stress to be welcomed by the Labor Party twenty-seven years later in the form of the new program adopted at Birmingham. In 1928, Ramsey MacDonald avenged John Burns by making the Labor Party declare at the Birmingham Conference:

“The Labor Party speaks, not as the organ of this class or that, but as the political organ created to express the needs and voice the aspirations of all who share in the labor which is the lot of mankind.” (New Program.)

How did this happen? How could the Labor Party revert to the traditions of anti-proletarian liberalism, the revolt against which marked its birth? The Labor Party has relapsed into the flagrantly anti-working class view and policy, which it condemned at its birth, because, at the same time, it refused to take its stand on a clearly defined Socialist policy, and began its career under ambiguous colors. Together with the liberalism of John Burns the London Conference also discarded the point of view that, in order to be really a party of the working class, the Labor Party must unequivocally subscribe to the principles of revolutionary Socialism, and lead the proletariat in the class struggle. The London Conference rejected a resolution which contained the following statement:

“That the representatives of the working class in the House of Commons shall form there a distinct party based upon a recognition of a class struggle, and having for its ultimate object the socialization of the means of production, distribution and exchange.”

This was not a comprehensive statement of the principles of revolutionary Socialism, free from the germs of opportunism and reformism. Nevertheless, the London Conference rejected it in favor of the following clearly opportunist formula proposed by Keir Hardie:

“That this conference is in favor of establishing a distinct Labor group in Parliament, who shall agree upon its own policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interest of labor.”

This loose formulation of the aim and policy of the party gave it a free hand to develop into anything but a revolutionary Socialist Party fighting consistently and resolutely for one object, namely the defense and promotion of the immediate and ultimate interests of the working class. No policy was fixed, and the “readiness to cooperate with any party” kept the way open for the resurrection of Liberal-Labor collaboration (or coalition) under changed conditions in the future. As nothing about the ultimate goal of the working class movement was mentioned, tacitly the new party was committed to reformism from its very birth. It was to be a political replica of the trade unions carrying on collective bargaining inside the parliament. From the opportunist course taken at the very beginning it can be logically inferred that what was desired by the promoters and founders of the Labor Party was that organized labor should have independent political organization with the object of holding high the banner of the traditions of philosophical radicalism, political democracy and social reform, betrayed by the bourgeoisie. This being the case, when today the leaders of the Labor Party proudly declare themselves as the defenders of true liberalism, they speak the historical truth and speak in the spirit with which the party came into existence. These opportunist traditions made it possible for the Fabian theorists, bourgeois radicals and trade union bureaucrats to combat successfully the penetration of the Labor Party by Socialism.

The proletariat, however, cannot for ever be kept away from the path of Socialism. Their very existence is a testimony for class struggle, which grows sharper simultaneously with the development of capitalist production. And the sharpening of the class struggle drives the proletariat toward the fight for Socialism. In spite of all obstacles, class-consciousness developed among the British proletariat. Finally, in the latter years of the World War, class-struggle became a reality of every day life, and Socialism was a practical question for the working class. Fabianism again came to the rescue. Indeed, it was for such emergencies that it had kept itself in readiness. Under the pressure of sharpening class struggle and growing revolutionary class-consciousness of the proletariat the Labor Party was obliged to accept Socialism as its goal. The fraudulent Fabian variety was useful to placate the masses without essentially altering the liberal ideology and outlook of the Labor Party.

In the new Constitution adopted in 1918 the aim of the party was stated as “to secure for the producers by hand and brain the full fruits of their industry, and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of common ownership of the means of production, etc.”

Under the pressure of the masses, actually engaged in class struggle, the Labor Party came to the verge of breaking away from the ideology of bourgeois liberalism. The Socialism falteringly accepted in 1918 exceeded the limits of Fabianism. For, by the resolution of 1918 the Labor Party admitted the right of the workers to the full fruit of their labor, which Fabian social engineering had declared impractical. The high priest of Fabianism, Sidney Webb, himself began singing the song of the “New Social Order” which it was Labor’s mission to create. The struggle between Socialism and Liberalism, which had gone on inside the Labor Party ever since its foundation, reached a critical stage. The forces of Socialism had gathered strength, and threatened to overwhelm those of Liberalism. The latter were obliged to manoeuvre for position. They decided to beat a strategic retreat which was a camouflaged attack. They saved the Labor Party for bourgeois liberalism by hoisting false colors. The move of the bourgeois liberal and conservative trade union leaders was successful. It sabotaged the development of the labor movement consciously towards the struggle for Socialism, and diverted it temporarily from the road of revolution. The masses were once again deceived. They were told that the Labor Party would take up the fight for Socialism, in accordance with their demand. But such a promise from the leaders, traditionally wedded to the anti-socialist doctrines of bourgeois democracy and social reform, was but an empty phrase, as it has been demonstrated now, after ten years.

Finally, the historic struggle inside the British Labor Party has ended in a complete victory of bourgeois liberalism. Therefore the task of the vanguard of the British proletariat is no longer the struggle for the capture of the British Labor Party, in order to transform it into a formidable weapon in the fight against capitalism; but to expose it and attack it as a political organ of the bourgeoisie endeavoring to induce the working class to help the reconstruction of the shaken structure of capitalist society.

NOTES

1. Report to the International S. and T.U. Congress of London in 1896.

2. The present policy of no election bloc, but government coalition essentially on the basis of bourgeois democracy and enlightened capitalism, is completely in accord with the spirit of the London Conference.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This Communist was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March, 1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v08n01-02-jan-feb-1929-communist.pdf