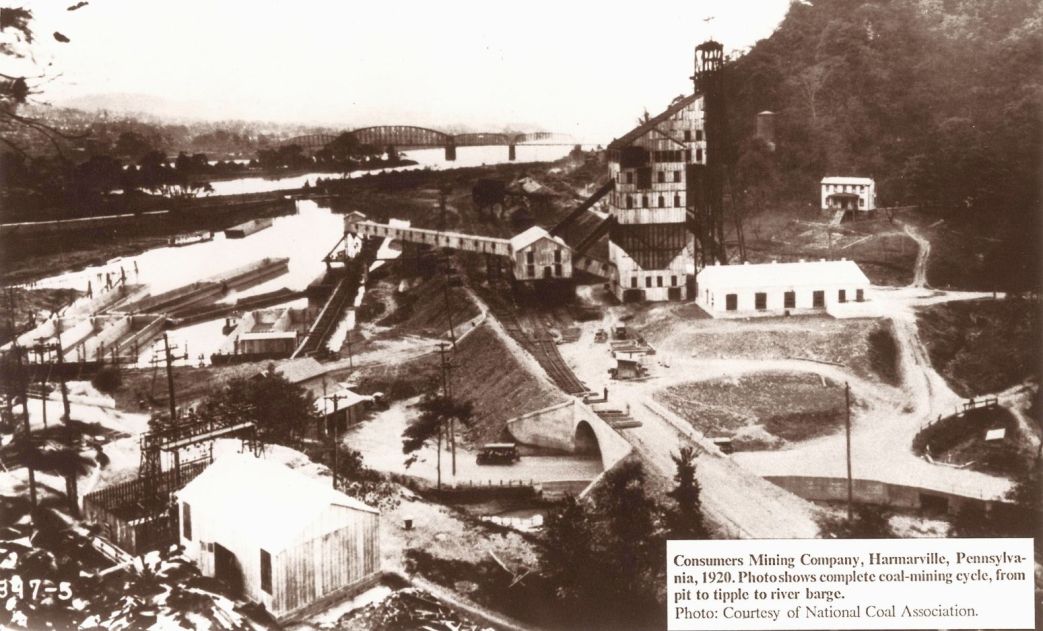

Every comrade who has been out too early on a morning picket line will feel this scene as Don Brown reports from Harmarville, Pennsylvania during the massive, insurgent strikes of union and non-union miners beginning in 1927 with the expiration of the Jacksonville Agreement. The strike would shatter the U.M.W.A. as John L. Lewis’ machine sold out the miners, consolidated power over regions and expelled political opponents, leading to a multiplicity of new miners’ unions in the late 1920s.

‘On the Pennsylvania Front’ by Don Brown from New Masses. Vol. Vol. 3 No. 8. December, 1927.

(Don Brown has just returned from Pennsylvania, where the miners are fighting a life and death struggle with the Mellon owned Pittsburgh Coal company and the Pittsburgh Terminal Coal company. Justice Schoonmaker, at the request of the latter company, has issued a smashing injunction against union picketing, on the grounds that the union is conspiring to prevent the shipment of non-union mined coal in interstate commerce.)

I staid with a family of mine people at Harmarville one night. We got up at 4:30 o’clock in the morning to go on the picket line. The wife of the miner had been up for some time. She gave us big cups of black coffee and lots of hot milk to go in it. We went down to the picket headquarters in the dark with the fog so thick and cold I could feel it crawling up my pants legs and sliding in under my collar. It was so thick you couldn’t see the headlight of a locomotive or as it roared along the tracks fifty feet away.

We joined the other pickets there. They let me have a U.M.W.A. badge and with seven “other” miners I went up to the picket posts. It felt like going on guard in the army. It was cold and miserable enough to be a wartime winter in France. Picketing starts at 5 o’clock. They put me on a post where a tunnel has been made under the raised road so the scabs can get into the mine without the pickets being able to get very near to them. You stand on the road just over the entrance of the tunnel and stare into the thick fog. After a while you hear men stumbling along in the dark in single file in groups of two or three or more. Just as they get directly under you to disappear into the dark tunnel, you can see them dimly for a second only.

Next to you stands a company guard with a polished club nearly three feet long. Impolite words to the scabs will bring it slashing down on your skull. Around a fire across the road you see the shadowy forms of other guards with other clubs protruding. With them are two state troopers whose snappy uniforms give a fine military appearance, even in a foggy silhouette.

Waiting for the first scabs to appear, everyone is silent, hunched up and shivering and regretting warm and comfortable beds in relatively safe places. The figures across the road are grim and so are the figures of the pickets.

A big miner of about twenty- our years whose name is Zeke begins to sing in the dark. He has a fine deep bass voice and he knows some swell songs. He must have worked further south than Pennsylvania because a lot of his songs are southern negro ones.

“Oh fetch me down my bottle of corn,

Oh fetch me down my bottle of corn,

Oh fetch me down my bottle of corn,

I’m going git drunk just as shore as you born!”

he roars and then

“Oh Mama come on and go my bail

And git me outa this lousy jail!”

Zeke has been in the mines since he was sixteen he told me later. He said he had wanted to be a miner ever since he could walk and it was a proud day for him when they let him go down with the other men. Zeke was a master of irony in talking to the scabs.

“Fine, big-hearted boys!” he would roar at the miserable sleepy scabs stumbling along in the dark. “Fine, big-hearted boys. They love the boss so well they load four tons of coal for a dollar and a quarter. You won’t buy no steaks with what you get outa this mine!”

Zeke sings some more songs.

“Hey Zeke, if you’re singing that song in parts you kin leave my part!” one of the guards calls out.

The picket on the other side has an approach very different from Zeke’s. He is friendly and gentle and persuasive–in his audible remarks. Under his breath he curses the scabs.

He calls out “Come on boys, what do you want to go down in the dark hole for? Just to help the boss? That’s all you’re doing. You’re helping him against us and yourselves too. You can’t live on what you get scabbing and you know it. Come on out of the mine and help us and we’ll all be better off!”

Under his breath he whispers,

“You dirty, lousy scabs. You’re all yellow or you wouldn’t be scabs!”

Mostly the scabs bow their heads and make no reply as they move along into the tunnel.

When he called out to one and said “Don’t you know you oughta be ashamed to go down there?” the man answered “Yes, I know it” and slouched on into the dark without looking up.

Another scab yelled, “Get rid of Lewis and I’ll come back into the Union with a lot more ‘like me!”

This picket detail goes off at 7 o’clock when the pickets go back to the Union hall where two of the women bring a basket of big sandwiches and a bucket of hot coffee. You eat the sandwiches and drink the coffee while it is still dark and cold and they taste good.

George and His Dog

GEORGE BINGULA is a Union miner out on strike. He lives at Harmarville, Pennsylvania and worked in the big coal mine there. He is a powerful guy, over six feet tall with broad shoulders, strong arms and a face small in proportion to his body. He looks a little like Bob Minor and a little like Honore Daumier. He comes from somewhere in middle Europe. He’s a good musician and is considered a necessity at the dances the mine people have in their Union hall so often. He has a wife and a little girl. He and the wife don’t speak English so very well but the little girl speaks it very well. She has a much better accent and speaks more distinctly than we middle westerners. She helps George and her mother tell things.

George has been arrested a few times by the coal and iron police or deputies at Harmarville. He has a bad name among them. He spit in a deputy’s eye one day during an argument on the picket line. They put him in jail but the mine people raised some money and bailed him right out because there was going to be a dance that night and they had to have George to play for it.

The other day one of the deputies filled up on raw liquor and got abusive when he met some of the strikers’ wives and children on the road. George came along and remonstrated and the deputy jerked out a pistol and shot George through the leg. The drunken deputy ran and George walked on up to his house. The bullet had missed the bone. The blood sloshing around in his shoe bothered him when he was walking, he said. When I saw him he didn’t seem to be downhearted about it. With some pride, he took off his shoe and sock and rolled up his trouser leg to show me the healing wound. He didn’t seem to have any personal feelings about the deputy who had shot him. Although he did refer to him as a son-of-a-bitch, he said it without venom, using it the same as the word “scab” or “yellow-dog.” He was irritated though at the actions of a doctor who had treated the wound and made him stay in bed several days when he wasn’t sick at all.

George has a funny looking black dog with strong traces of dachshund ancestry and a grey-whiskered thoughtfully humorous face. One day the dog went across from the picket headquarters at the Red Raven store in Harmarville and started playing with a coal and iron deputy. George called his dog back and beat him up good and proper. He beat the dog up so bad he had to take it in his arms and carry it back to the road half a mile to his house. “Don’t never go scabbin’ again!” he told the dog as he beat it up and the deputies and pickets looked on. The dog got the idea all right and won’t go near a deputy now. He strolls down to the union head-quarters every morning and plays with the miners. They laugh and say, “There’s the dog that went scabbing but he don’t no more.”

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1927/v03n08-dec-1927-New-Masses.pdf