It is entirely true to say that the labor movement in the country has failed the ‘test’ of race; it is also true to say that the labor movement is the ONLY site where it has even attempted to be ‘solved.’ When William D. Haywood lent his hand during the Brotherhood of Timber Workers strikes of 1912-13 he noticed that Black and white workers in the same union met separately, and demanded that if they worked together, they meet together. The I.W.W. made it a point of their organizing, despite the resistance of some white members, and breaking to color line in jim-crow Louisiana and Texas was no small feat, or humble endeavor. It was conscious and it cost workers’ lives. Here, E.F. Doree speaks to the workers’ need of the union of a union.

‘Stomach Equality’ by E.F. Doree from The Lumberjack. Vol. 1 No. 5. February 6, 1913.

Perhaps the greatest question confronting the industrial unionist today is the foreigner and race question. In each section of the country we find the American born shouting himself hoarse against the Italian, Greek, Sweed, Russian, Jew, Jap, Chinese or Negro. That the writer was American born he does not deny, but that it was due to his good judgment prior to birth he takes this occasion to deny. So if some of us were born here it was because our fathers and mothers came here and were damn foreigners in our stead. But in the South the great issue is not “the dago,” “hunkie,” “slant-eye,” “round head,” or “blue nose”–it’s the “n***r.”

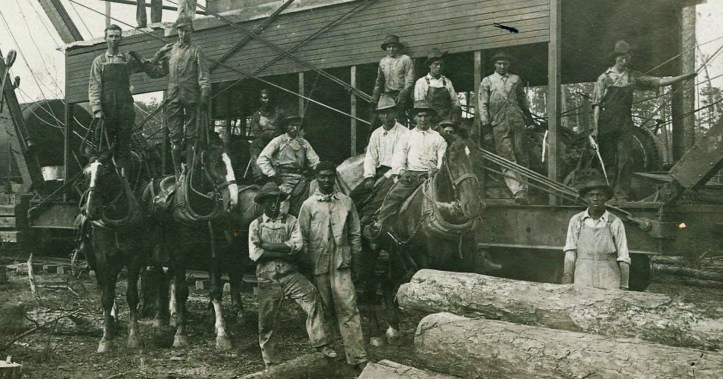

What are we going to do with him? He saws logs, he works in the mill, he piles lumber, produces turpentine– well, in fact, in and on almost every job you find him working side by side with a white man. You must admit that he is a wealth producer and as such deserves recognition.

The working conditions of the South are in a terrible shape. Long hours, short wages, hospital, insurance, and doctor fees, two roomed shacks set in a swamp to live in, unprotected machinery to work around, in the winter the rain and mud, and the summer hot and dusty, with its mosquitos and fevers. The working conditions of the Southern Lumber Operators Association is Hell. The object of the I.W.W. is to change these conditions and in order to get the economic power necessary to force this change it is incumbent upon us to organize the negro.

But some say, “I won’t belong to a union that takes in ‘n***s.’” I should like to ask what good a union would be in the South that didn’t take him in. With the negro in one union and the whites in another, all you would have accomplished would have been to create race wars, after which your wages would not be raised one cent, but, instead, in all likelihood, if you fight one another hard enough, the boss will cut your wages and make you like it. Your forces are divided.

There is one thing self-evident: Labor must be organized as compactly as possible. The American, the foreigner, Jap, and the Negro must be organized in the Union as they work. If they work together, organize together.

You ask, “Shall we meet in the same hall at the same time?” Do you meet in the same mill at the same time? If so. “Yes.”

But, even at that, the I.W.W. has made provisions for branch locals whereby one race or nationality can meet at one time and place and the other race or nationality at another place and time. But this is not so concrete as meeting together. You may not like it at first, but if you can work with a negro for ten and eleven hours a day, you can surely meet with him one hour a work to make plans by which to get more wages or fewer hours of labor or other concessions from a common master. You may call this “social equality,” but we call it “stomach equality.” If the I.W.W., which is the result of 5,000 years of triumphs and failures in the labor world, will not take the unqualified stand for the solid organization of all races, there will appear, as surely as the sun shall rise in the morning, another organization that will and it will supersede the unions of today, because of our failure to unite all of the workers together.

Call this anything you like, but this is what labor must do to win. Now all you workers, white and colored, get into the One Big Union, the I.W.W. See your closest Union Secretary or write Jay Smith, P. O. Box 78. Alexandria. La. The initiation is $1.00: dues are 50 per month. Kick in–be one thing, a man, a union man, an I.W.W.

The Voice of the People continued The Lumberjack. The Lumberjack began in January 1913 as the weekly voice of the Brotherhood of Timber Workers strike in Merryville, Louisiana. Published by the Southern District of the National Industrial Union of Forest and Lumber Workers, affiliated with the Industrial Workers of the World, the weekly paper was edited by Covington Hall of the Socialist Party in New Orleans. In July, 1913 the name was changed to Voice of the People and the printing home briefly moved to Portland, Oregon. It ran until late 1914.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/lumberjack/No.05.pdf