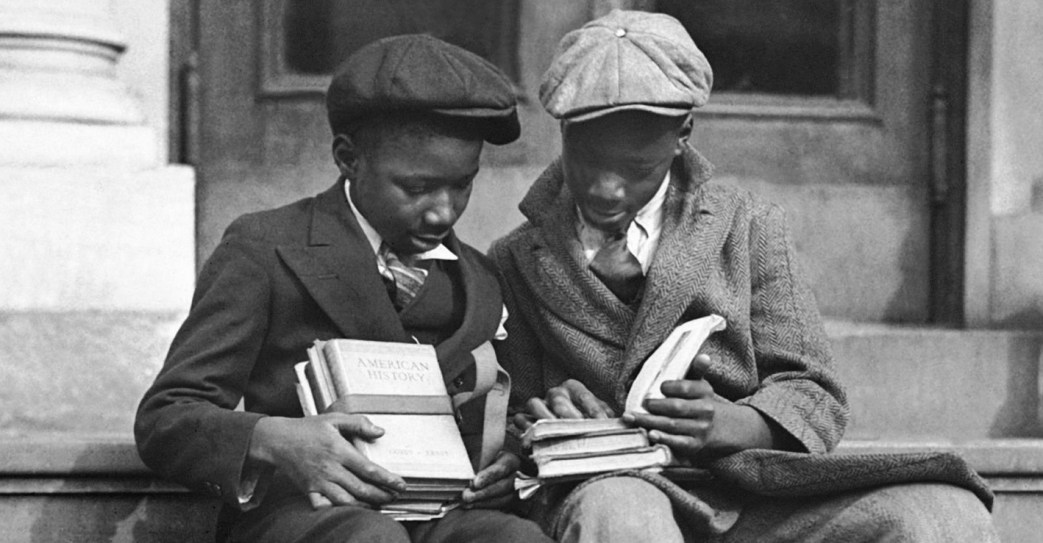

A survey of the anti-Black text books students were made to read in the New York City Public Schools in the 1930s.

‘High School Texts and the Negro’ by Aaron T. Schneider from Student Review (N.S.L.). Vol. 4 No. 4. April, 1935.

The textbooks used in New York City High Schools reflect the deep-rooted discrimination against the Negro people which has shown sharper and more spectacular form in our campus struggles against “Jim-Crowism” in the schools. Even a cursory study of these texts teach us to be alert and critical of the material offered for study in our classrooms,

Bourne and Benton’s text, “A History of the United States” treats the education of the Negro as a problem which can be solved by a Jim Crow policy; they speak of industrial schools for Negroes to be farmers, workers, and teachers of their own race. On page 480, they recommend Hampton and Tuskegee, and beyond that they have nothing to say of education for the Negro. Bryce’s “Modern Democracies,” Volume II, pages 546-547, attacks the giving of the suffrage to the Negro in the Black Belt:

“In the Southern States of the Northern American Union, the extinction of negro slavery was followed by the overhasty grant of full political as well as private civil rights to the emancipated slaves. The suffrage has been gradually withdrawn from the large majority of the colored people of the South but a minority are still permitted to vote, and much controversy has arisen to their moral claim and their fitness.”

Even a McKnight or a Huey Long couldn’t do better!

Cornish and Hughes, “History of the United States for Schools,” repeat the usual lies about the Reconstruction period with such phrases as, “In the South the negroes who had so suddenly gained their freedom did not know what to do with it”; or, “sole legislatures were made up of a few dishonest white men and several negroes, many too ignorant to know anything about lawmaking.” Another important statement in this book is significant since it has been leveled against both Negro and white relief workers of the present day, “The relief in the form of food and clothing made some of the Negroes think there was no settling down and going to work.” (page 346.)

The great historian, John Fiske, in his “A History of the United States,” also repeats the lies of the slanderers of the Negroes of the Reconstruction period. Emerson David Fite, author of the text, “The United States,” may also be placed among these enemies of the Negro people. On page 37, he says of the Reconstruction period, “Foolish laws were passed by the black lawmakers, the public money was wasted terribly and thousands of dollars were stolen outright. Self-respecting Southerners chafed under the horrible regime.” He does not see fit to mention any of the constructive laws or progressive measures taken by the Negro. He omits all the Negro anti-slavery uprisings, the importance of the Negro in the Civil War, and, of course, the development of the Negro since the Civil War.

Mr. S.E. Forman, who is enjoying the royalties from three books in use in the high schools of New York City, is certainly not without guilt in his treatment of the Negro question. In his “Advanced American History,” he repeats all the slanders in connection with the Reconstruction period. Of course, he does not mention the contribution of the Negro to education, to art, to literature, etc. In his “Rise of American Commerce and Industry,” he likewise leaves out the contribution of the Negro. In his book on civics, “American Democracy,” there is no mention of the Negro question either in the Black Belt or in the North.

In Gautteau’s, “The History of the United States,” we find on page 484, the typical Reconstruction lies. R.O. Hughes’, “Economic Civics” does not see fit to even mention the Negro. Now we come to an old friend of the American student, Professor David Saville Muzzey. He, in both his books, “An American History” and “History of the American People,” attacks the Negro race of the Reconstruction period violently and leaves out entirely the progress they have made since their freedom from slavery.

Arthur Meier Schlesinger’s “Political and Social History of the United States” devotes a great deal of space to the Negro question, and often gives a great deal of valuable information, but this book, too, repeats the stories of the Reconstruction period. Professor Tryon and Lingley’s book, “The American People and Nation,” also gives the usual Reconstruction story, and in their chapter on “Discoveries and Inventions” leave out entirely the role played by Negroes in the field of science and invention. Ruth and Willis Mason West in their book “The Story of Our Country” follow the Jim Crow line of the Negro reformists and Uncle Toms. On page 405, they say:

“His education, his rights, his relations to white men is still unsolved. Only the first steps have been taken. The Negroes of the new generation are self-supporting; thousands of them are in professions, a lawyers, doctors, editors and ministers, negro leaders have arisen like the late Booker T. Washington and his successor, Robert Moton, who have spent their lives in helping the people of their race “find themselves.” By their efforts, industrial schools have been founded to train the negroes in farming and various trades.”

On page 406, they come clearly to the point with their advice to the Negro people:

“Most negro leaders feel with the white men of the South that the two races are better apart—for the present at least. But they do not wish their people to be treated as inferiors. They insist that the ‘Jim Crow’ car shall be fitted up as well and kept as clean as the white man’s; and that the schools to which the negro sends his children shall have their proper share of public money so that they may have as good teachers and good equipment as the schools for white children. This kind of equality has—not yet been fully secured. For this reason, many negroes are leaving the South for other parts of the country where they hope for wider opportunity.”

Their solicitude for the Negro people, however, does not prevent them from giving currency to the usual stories of the Reconstruction.

These are a few of the type textbooks which students must be wary of. The fight for Negro rights, as the fight for all the demands of the student body, must be fought on all fronts.

Emerging from the 1931 free speech struggle at City College of New York, the National Student League was founded in early 1932 during a rising student movement by Communist Party activists. The N.S.L. organized from High School on and would be the main C.P.-led student organization through the early 1930s. Publishing ‘Student Review’, the League grew to thousands of members and had a focus on anti-imperialism/anti-militarism, student welfare, workers’ organizing, and free speech. Eventually with the Popular Front the N.S.L. would merge with its main competitor, the Socialist Party’s Student League for Industrial Democracy in 1935 to form the American Student Union.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/student-review_1935-04_4_4/student-review_1935-04_4_4.pdf