A valuable look at the proletarian theater movement in Japan during the 1920s and early 30s.

‘The Revolutionary Theatre in Fascist Japan’ by Seki Sano from Literature of the World Revolution. Vol. 1 No. 5. 1931.

The first workers’ theatres in Japan were organized by the dock strikers of Nobe (1921) and by the printers of Tokio (1925). These theatrical groups soon made room for the “Trunk Theatre,” so called because the entire stage properties could be packed in a small trunk.

The Trunk Theatre was formed by radical intellectual elements who had taken part in the revolutionary proletarian movement almost from its very beginning.

Five years have elapsed since the formation of the Trunk Theatre, five years of stubborn struggle against opportunism, eclecticism, and social-fascism.

One typical example of the influence of the revolutionary theatrical movement on the Japanese theatre is the case of a few young actors of the classical school of Kabuki, a theatre with a past history of three centuries and now one of the most powerful weapons of the ruling class in Japan. In June, 1931, these young actors revolted against the Kabuki traditions and organized the Dzen Sin Dza (progressive theatre) in which left tendencies predominate.

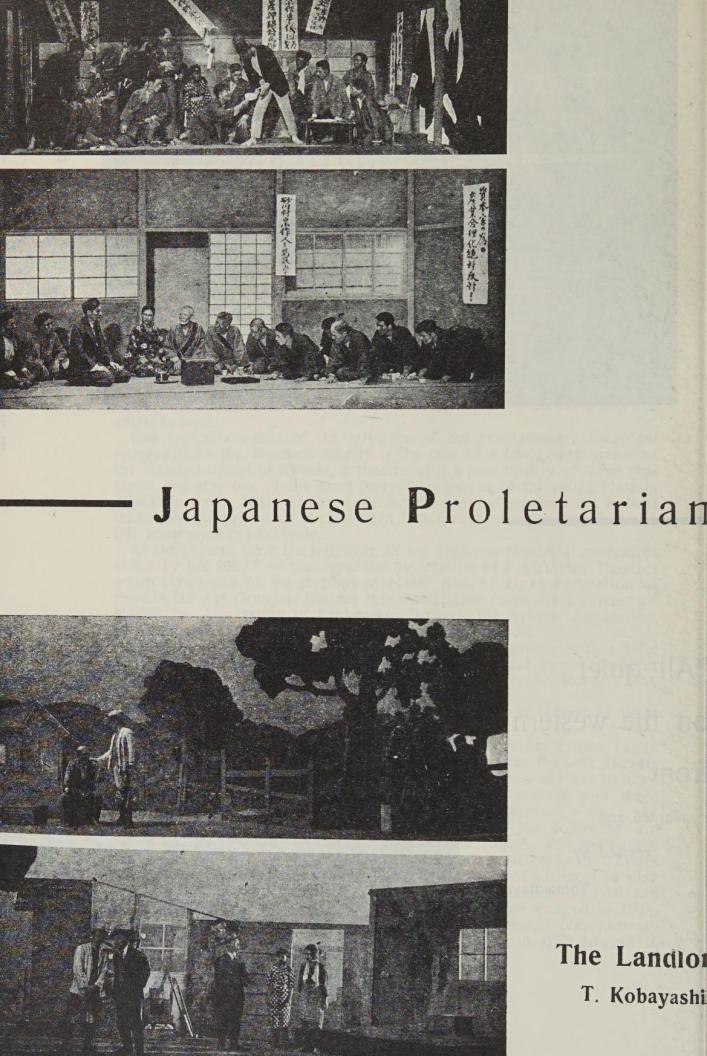

At the present time the left wing of the Japanese theatrical movement is led by the PROT—the Japanese Association of Proletarian Theatres which forms one of the sections of NAPF (the All-Japan Federation of Proletarian Art Groups). Besides this Association there are affiliated to NAPF: the Association of Proletarian Writers, the Artists’ Association, the Cinema Association, and the Musicians’ Association.

PROT comprises at the present time 12 theatrical groups with a total of about three hundred members scattered throughout Japan (three at Tokio, and one each at Nisuoka, Nagoya, Osaka, Kyoto, Kobe, Kochi, Matsue, Kanasava, and Matsumoto).

The Left Theatre of Tokio is one of the oldest and largest of these groups.

The “Trunk Theatre,” out of which the Left Theatre has grown, began its activity with five or six workers. At the present time the Left Theatre embraces about 80 members working in seven sections and has its own producers, actors, electricians, decorators, costume makers and stage setters, all of whom give their services without payment.

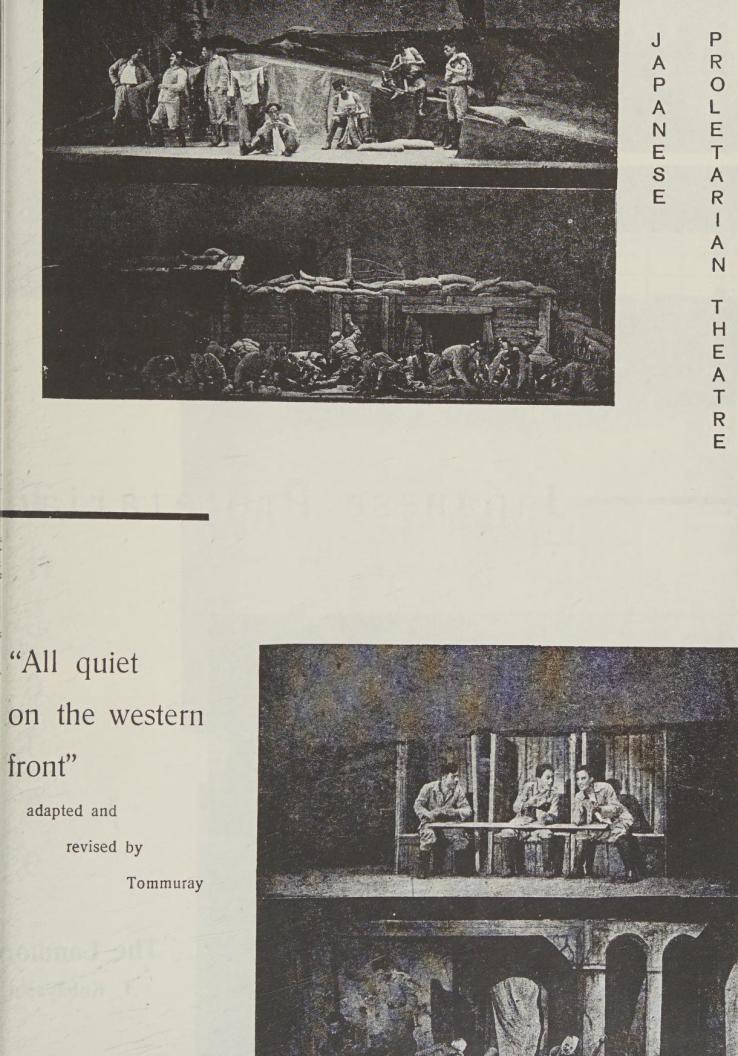

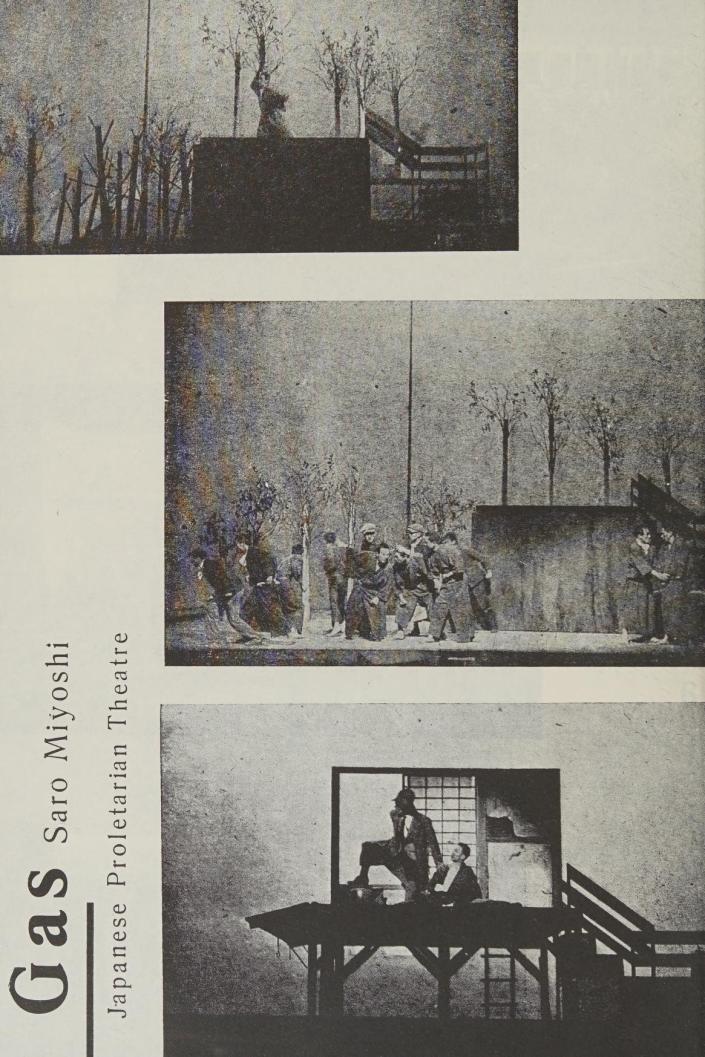

Among the plays produced in the Left Theatre the following are worth mentioning: “Emancipated Don Quixote” by A.V. Lunacharsky (staged by the “Vanguard Theatre,” the new name assumed by the “Trunk Theatre” since 1926); “Crucified Modzaemon,” by S. Fudzimori, a play depicting the peasant riots of the Tokugawa period (staged in 1928 and banned by the censor); “The Debacle,” by B. Lavrenev (staged in 1928, also banned); “All Along the Line,” by Toma Muroyama, a play portraying the big strike on the Peking—Hankow railway in 1923 (staged in 1919); “The Sunless Street,” by Tokunagi Naoshi, a play showing the printers’ strike at Tokyo in 1926 (staged in 1930); Remarque’s “All quiet on Western Front,” adapted by Toma Muroyama (staged in 1931), and “Victory,” by Toma Muroyama, depicting the revolutionary May Day demonstrations of the Chinese proletariat in 1930 (staged in 1931).

Besides the Left Theatre, mention ought to be made of “Sin Tsukidgi Hekigan” (the new Tsukidgi troupe). It is a petty-bourgeois dramatic group known also under the name of the “Little Tsukidgi Theatre,” founded at Tokio in 1925. Ideologically it resembles the “Theatre Guild” of New York, or the “Theatre du Vieux Colombier” of Paris.

In 1929 the majority of this group formed the new theatre “Sin Tsukidgi” which affiliated to the Left Theatre, and in May 1930 joined the PROT. Its best productions were the following: “Mother,” by Maxim Gorky; “Uprising,” by Fudzimora; “Roar China,” by Tretyakov; “Armored Train,” by Ivanov (banned by the censor); “Echo,” by Bill-Belotserkovsky; “A Descendant of Genghis Khan,” (adapted from the original), and “Oriental Carriage Works,” by Toma Muroyama.

Besides these “big” productions, which usually run for two or three weeks continuously, there are the so-called “small” and “medium” productions. The latter consist of one or two-act playlets that are staged in working class quarters in connection with some revolutionary events (e.g. the campaigns dealing with the brutal police raids on homes of Japanese communists in 1928 and 1929, on May Day, on the anniversary of the October Revolution, etc.)

The “small” productions are given by a cast of three or four actors. The plays are of propaganda character, and are naturally banned by the censorship. One of the most efficient among these little troupes is the “Itinerant Proletarian Actor Troupe” of Tokio. Moreover, most of the proletarian theatres are now taking up banned and mutilated plays.

Although the big and medium productions are considered legal, they are nevertheless frequently so mutilated by the sundry censoring organs (the “Law and Order Section,” the “Red Brigade,” the “Gendarme Corpus,” and the police) as to be rendered almost entirely worthless. This is partly combatted by the Dramatic League which has its nuclei almost in every factory, and which prints and circulates illegally the passages deleted by the censors.

The same organization distributes cheap tickets among working people from 15 to 30 cents and from 71/2 to 15 cents each), and explains the real aims of the plays, thus carrying on agitation among the masses.

The “Left Theatre Dramatic League” is the largest illegal organization of this kind in Japan. It publishes a monthly review “Dohsi” (Comrade) in which the 3,500 members of the League exchange views and suggestions on the work of the theatre. It should be noted that the proportion of worker playgoers has steadily grown since 1929. Thus, in Tokio it has reached 78 per cent.

The plays are created either collectively or by improvisation. The first method is employed by the “Association of Proletarian Playwrights” in Tokio which has about twenty members. The improvisation method is naturally more suitable for the itinerant “agitprop” troupes. All the members of the theatre analyze and alter the play, working out the details of its production to suit the purposes of the class struggle.

Associated with the Left Theatre of Tokio is the “Proletarian Theatre Institute” which trains future theatrical workers. The Institute has about forty members; it conducts half-yearly courses in dramatic theory and practice.

Alongside of the revolutionary organization of NAPF there are also social-democratic art groups, like the “Rono Geijutsuka Renmei” (several splits have occurred in this group). Since the last split in May, 1931 the group is entirely ignored by the masses. It publishes an official organ “Bunge-Sensen” (Literary Front) on whose editorial staff are some of the decadent exponents of social-democracy (Koitchiro Mayedako—a Japanese “Upton Sinclair,” Suyakchi Aono, Jobun Kaneko, loshiki Hayama, etc.). It was this group that sent the open letter of protest to the Japanese Commission of the 2nd World Congress of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers. The reply of the Kharkov Conference, showing up the demagogical character of this group, was published in the October issue of “New Masses.” At the same time it ought to be mentioned that the majority of the members of this theatre have since joined the Left Theatre of Tokio.

NAPF is the only proletarian art federation in Japan that is working under the distinct influence of the Communist Party of Japan. The official organ of NAPF, published under the same title, carries on in spite of cruel persecution by the ruling class of Japan.

In an article by Comrade Furukawa in the June, 1931 number of “NAPF” the following is said among other things:

“The Japanese proletarian culture movement has made considerable progress in the field of art. Nevertheless, other important branches (anti-religions Propaganda, sport, radio, educational-scientific, Esperanto movement) have been largely neglected. The sport, science, educational, Esperanto and anti-religious movements have already their own organizations, Dut they have not yet been drawn properly into line with NAPF. In order to be really active as one of the elements of the communists movement in Japan, all the proletarian culture organizations, including NAPF, should be centralized into one federation on all-Japan scale. The five associations composing the NAPF should form part of this all-Japan federation. The leading workers of this new federation should interchange delegates with the Communist Party, in order to ensure the proper political development of the federation. At the same time the associations that are going to make up the new federation (the Associations of writers, theatrical workers, artists, sports, antireligion, radio, cultural-educational and Esperanto) should affiliate to the corresponding international organizations…At the conference of the five associations of NAPF held last year, steps were taken for directing the entire revolutionary art movement along definite communists lines. This year we ought to reorganize all the associations of NAPF, incorporating in them the hitherto neglected workers’ and peasants’ art groupings, in accordance with the criticisms given by the masses of our last year’s activities in the factories. In this manner we shall prepare ourselves for the forthcoming stage in our movement…”

The 3rd Congress of PROT, despite provocation and repression by the authorities, was held in Tokio on May 17 last.

One of the most important resolutions adopted by the Congress in connection with the Profintern Theses on revolutionary cultural and educational activities and the decisions of the 1st Congress of the International Workers Theatrical Movement stressed the necessity for increased initiative of workers in the theatrical movement. Concretely, it urged the necessity:

1. To organize and strengthen the dramatic troupes in the factories.

2. To increase the proportion of workers in the theatres now comprising the PROT.

3. To work out repertoires through collaboration of the theatres with the proletarian spectators.

Further, the Congress outlined the following tasks: to extend the PROT organizations among all important urban and rural centres of the population; to strengthen the Dramatic League under worker and peasant leadership; to combat the bourgeois and social-fascist theatrical movement; to put an end to the persecution of the proletarian theatrical movement through the support of the masses, and to form fraternal alliances with our brothers by class in China, Korea, and Formosa.

The Japanese revolutionary culture movement has succeeded in establishing a firm position for itself in spite of bitter persecution by the forces of fascism. Nevertheless, in order to ensure further development of the revolutionary culture movement in China, India, USA, Mexico and other Latin-American countries, as well as in Japan itself, it is essential to establish closer ties with these countries. With this purpose in view, steps have been taken for the creation of the first Pan-Pacific Secretariat of the Proletarian Culture Movement.

Literature of the World Revolution/International Literature was the journal of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers, founded in 1927, that began publishing in the aftermath of 1931’s international conference of revolutionary writers held in Kharkov, Ukraine. Produced in Moscow in Russian, German, English, and French, the name changed to International Literature in 1932. In 1935 and the Popular Front, the Writers for the Defense of Culture became the sponsoring organization. It published until 1945 and hosted the most important Communist writers and critics of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/literature/international-literature/1931-n05-LWR.pdf