The husband and comrade of Mary E. Marcy, Leslie H. Marcy, was also a fine revolutionary journalist and writer for ISR. Here he is with the story of thousands of largely Polish workers, doing 6-day, 84-hour weeks for $2.50 a day, and without a union, in a desperate strike against John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil and Tidewater Petroleum. Intense violence between local police, security guards, ‘deputies’ and strikers with their supporters lasted 8 days, with several refineries burnt to the ground. Eight-six workers wounded, and five killed. The strike ended with the Governor ordering mass arrests of strikers and security guards, while refusing to call out the National Guard. The workers won an 8-hour day and a small increase in pay. The following October, the strike was on again and for two weeks riots raged, with four workers dead and hundreds injured. This time, with no concessions.

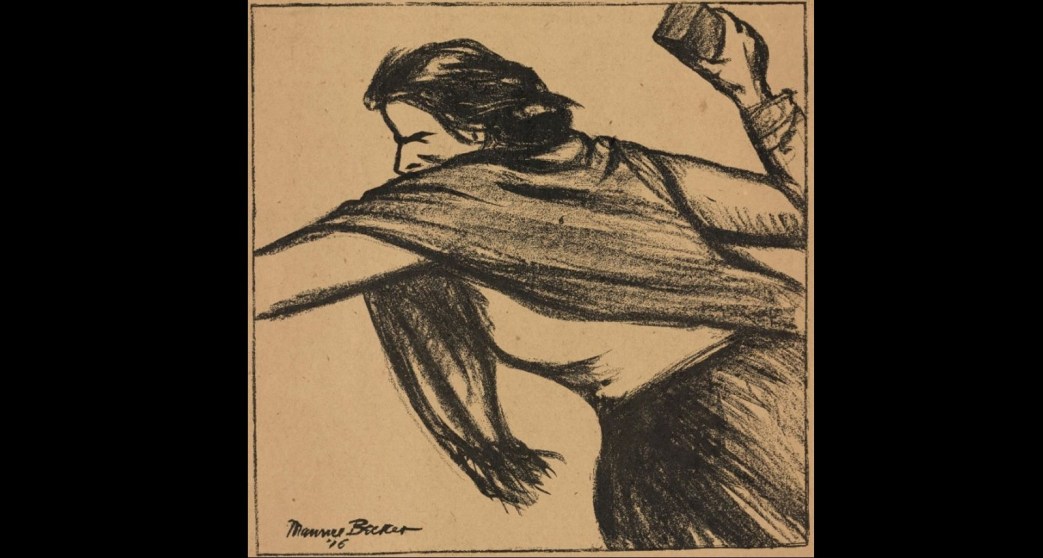

‘The Battle of Bayonne’ by Leslie H. Marcy from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 16 No. 3. September, 1915.

FIVE THOUSAND oil workers in Bayonne, New Jersey, are taking more money home in their pay envelopes on Saturday nights as the result of their spontaneous strike against the Standard Oil Company on July 14th.

They were not “free American citizens,” but mostly foreign-born Poles and Lithuanians, known on the payroll by the numbers on their brass checks.

But their splendid solidarity overwhelmed all odds; lack of organization and language differences, a double-crossing sheriff and 500 Waddell thugs armed with Standard Oil repeating rifles. Solidarity won and always will.

Chairman Frank P. Walsh of the U.S. Industrial Relations Committee sent two of his ablest investigators to Bayonne, who have reported in part as viz.:

“The Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, although conducting an enormously profitable enterprise, pays wages too low to maintain a family on a comfortable, healthful and decent basis. In Bayonne it paid common laborers at a lower rate than those of two companies whose plants adjoin its refinery. This is in direct contradiction to the claims of the company in a statement issued at 26 Broadway, New York, that it always has paid the prevailing wage or better.”

The still-cleaners, 100 strong, started the strike by asking a 15 per cent raise, which was promptly turned down and their committee fired. Their wage was $2.45 for working long hours in a temperature of from 200 to 300 degrees — scraping tar.

The barrel makers demanded 10 per cent and quit work. The strike spread until every man was out. Box and can workers, pipefitters and boilermakers, case makers and yard laborers.

The Industrial Commission report continues:

“On Wednesday, July 21, the Standard Oil Company began the importation of strike- breakers and ordered a large number of armed guards from Berghoff Bros. & Waddell, a strikebreaking and detective agency, of 120 Liberty street, New York City. As the strike-breakers were proceeding up Twenty-second street, on their way to the plant, they passed through a crowd of about 300 strikers.

Trouble immediately ensued and the strikers were rapidly reinforced. A detachment of police immediately charged the strikers. Some of these police were mounted, some on foot. The charge, however, was ineffectual, as the strikers’ rocks proved more effective than the clubs and revolvers of the police. Guards of the Standard Oil Company came out with their nightsticks to help the police, but they, too, were forced to retreat. Some of the police and company’s guards were forced into a fire engine house for refuge, and others surrendered to the strikers. One of the strikers, a boy 19 years of age, was shot through the head and killed. This was known as the “Battle of the Black Ditch.”

In Harper’s Weekly for August 7, while the strike of the Standard Oil employees was still young, Amos Pinchot said:

“Last Wednesday the strikers stood around the streets. There had been no fighting till then.

Then armed guards came in. They were not police, not deputies, but simply private individuals recruited by the company in anticipation of trouble. But they did not stay on the company’s property. They marched the streets and dispersed the crowd, shoving the men along, and telling the women to go home.

“That started things.”

“We went up in the air,’ one of the strikers told me. ‘They’d a right to stay on the company’s grounds. Why did they come right out in the town and club us off the sidewalks? They didn’t own the streets, did they?’ Fist fights started, clubs rose and fell, stones flew, pistols were drawn, and the 44 calibre Winchesters of the mine guards barked while the crowd surged toward the company’s gates.”

“A reporter said to me, ‘I have never seen anything like it—the sheer grit of these men. Twice, practically unarmed, they charged the ten-foot stockade from behind which the guards were picking them off with Winchesters. About a hundred actually scaled it, swinging and pulling each other up, while the women and children cheered them. It was like one of those cavalry drills at Madison Square Garden. Only the difference was that a quarter of them were shot down before they reached the ground on the other side. If the guards had shot better they’d have got all of them. Even the kids are in this strike. They gathered stones and sailed in with the men. A bunch of little chaps from ten to fifteen years old sneaked up to the fence and lighted a fire to burn it down. They wanted to make a hole for their fathers and big brothers to go through. I saw one youngster catch a loose police horse, crawl on its back and ride up to the stockade, swinging his cap and yelling while the men charged.”

“Now for the cause of the strike. Contrary to my preconceived idea, the Rockefeller employees at Bayonne are not well treated. They are underpaid and live in greater poverty and squalor than even the workers of the fertilizer companies who struck last winter at Roosevelt. A school teacher who seemed to know what he was talking about said that from six to ten families often live in a two or three story frame house. Among the lower paid men it is a steady struggle against want. Here are some of the wage scales told me by strikers who gathered around us at the bullet scarred shanty which is used for headquarters.

“Another grievance was what they called the new management. Under the old management a list of names went into headquarters three times a year of men recommended for increased pay. Since the new manager came, no such lists have gone in. Again, for the work of dumping the wax presses, Hennessy, the new manager, reduced the number of gangs from fourteen to ten. Thus about a quarter of the dumpers were laid off, and the men left on the job claimed the work was too hard. One of them told me that a man often worked 168 hours in two weeks, with one twenty-four hour shift when the night shift is changed and becomes the day shift.

“These are some of the causes of the strike — there are others—which rose first to the strikers’ minds, as they talked; and then there was the feeling that the company, which they believed to be making big money just now, could especially well afford to raise wages to a living scale.”

In the report made by Messrs. West and Chenery to Mr. Walsh we read that on

“Thursday afternoon guards from the Ascher agency, of New York, reached the property of the Tidewater Company, and that evening took charge of the patrolling of the works. These men had evidently been hastily picked up, for they showed no familiarity with firearms or knowledge of discipline. In fact, so awkward were they with the rifles that one guard accidentally shot one of his fellows in the ankle, necessitating amputation of the leg. The men were utterly irresponsible and kept on firing indiscriminately during the night, either to test their weapons or through sheer nervousness. This continual firing, of course, enraged the strikers and kept things in a ferment.

“The commander of the Ascher men had been one of those in charge of the guards at Roosevelt in January, when these guards killed or wounded twenty strikers. The company was so alarmed by the conduct of these men that the next day at noon they summarily discharged them and substituted men from the Berghoff agency in their place. These Berghoff men were also hastily recruited and were characterized by the Berghoff attorney as a lot of irresponsible thugs. The organization of the Berghoff Company, though, was far superior to the Ascher guards. After their substitution there were no casualties.

“Thursday, July 22, at noon, saw the last serious clash. During that night, however, there was occasionally an exchange of shots between the company guards and the strikers, who were on roofs of houses taking pot shots at the guards.

“The leader of the strike had been a young Elizabeth City Socialist by the name of Jeremiah Baly. He was a salesman employed by the Singer Sewing Machine Company, and had come to Bayonne at the commencement of the trouble. He had taken part in several discussions of the situation and had at several times addressed the crowd of strikers. Sheriff Kinkead was impressed with this young man and suggested to the strikers that they select him as a member of the Strike Committee. This the strikers did and he represented them in their committees which went to see the company officials and in negotiations with the city authorities.

“The men all had back pay coming and after much dispute it was finally decided that they should go in groups inside the Standard Oil stockade and get their pay at the window. The sheriff insisted that Baly go in with the first number, as he alleges that he was not aware that Baly was not an employee of the Standard Oil Company. Baly entered with those men and then, in the presence of the armed guards and deputies, the sheriff ordered Baly to go to the window and get his money, and Baly refused. The sheriff then assaulted him, knocked him down and beat him viciously. He placed Baly under arrest and put him in the Bayonne jail.

“Frank Tannenbaum, an I.W.W. leader, who was at Bayonne in the interest of the strikers, was also arrested Monday. By Tuesday many of the strikers were willing to return to work and the sheriff, who by this time had 500 deputies and 140 uniformed police, stationed them at intervals along the route to the plant, and about 1,500 strikers returned to work. The company then began to discharge their guards, and by Wednesday morning practically the entire force was back at work and during the day all of the armed guards had left for New York, with the exception of 100 at the plant of Tidewater, whom Sheriff Kinkead had arrested on the charge of inciting to riot. These men were all given a hearing before Police Recorder Kain, of Bayonne. All but ten of them were discharged. These men are out on a $1,000 bail each.”

“Two days after the men had returned to work the Standard Oil Company announced increases in the wages of its common laborers and proportionate increases for other groups’

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v16n03-sep-1915-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf