A joy to read. Two letters of Engels on addressing literature full of his knowledge, insight and diplomacy. The first, and richest, to Ferdinand Lassalle from 1858 with a critique of Lassalle’s play ‘Sickengin,’ and to Minna Kautsky from 1885 on her works ‘Stefan,’ and ‘The Old and the New.’

‘Two Letters by Frederick Engels on Literature’ from International Literature. No. 11-12. November-December, 1940.

We have already had occasion to draw the attention of our readers to the fact that Marx’s and Engels’ literary heritage contains many observations on various problems of literature and art. (See International Literature No. 12, 1939, p. 84.)

Special and well deserved attention has been drawn by a letter addressed by Engels to the German authoress Minna Kautsky. In it Engels defined with remarkable precision and clarity the role and task of tendentious literature in the history of man.

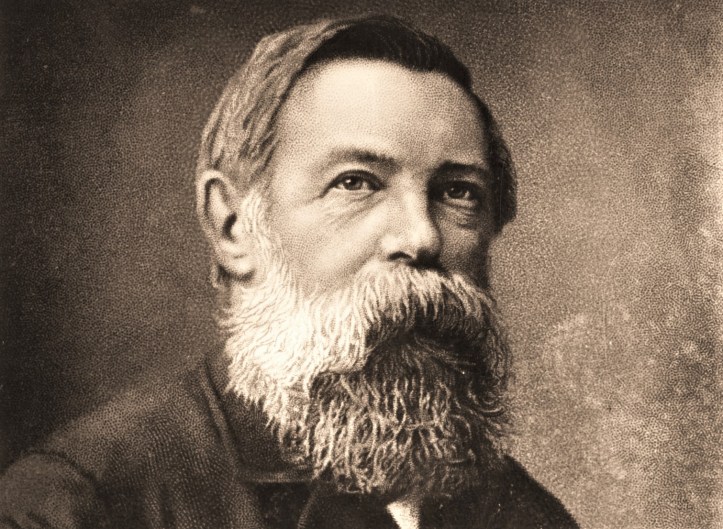

On the occasion of the 120th anniversary of Engels’ birth, we print this letter, as well as one addressed to Lassalle, discussing vital problems facing playwriting. They are translated from the German. The value of his observations is enhanced by the fact that they outline the path along which dramaturgy will inevitably develop in the future. The eighty years which have elapsed since that letter was written have fully confirmed the ideas expressed by Engels.

The letter to Lassalle discloses the great importance Engels attached to literary problems. This is evident from the very fact that he had read Lassalle’s play four times before pronouncing judgment.

The reader, of course, must bear in mind that these letters were not intended for publication. While expressing on the whole a favorable opinion of the works by Minna Kautsky and Ferdinand Lassalle, in which he saw first shoots of Socialist literature, Engels carefully and tactfully pointed out to them the basic weaknesses of their works.

A number of other statements and observations on literary problems by Marx and Engels which hitherto have not been translated into English, will be printed in International Literature in 1941.

LETTER TO MINNA KAUTSKY

London, November 26, 1885.

Dear Mrs. Kautsky:

(Permit me to use this simple form of address—why should two people like ourselves indulge in pomposities?)

First of all, hearty thanks for your kindness in remembering me. I am very sorry I did not have the opportunity to spend more time with you here; I assure you I was infinitely pleased for once to make the acquaintance of a German authoress who has not given up being a plain woman—I had been unfortunate in this respect, since | had known only those affected “educated” Berlin ladies whom you would not send back to their pots and pans for the only reason that they would make even a worse mess of it than with their pens. And so I hope that you will soon cross the Channel again, and I’ll have a chance to take you on some rambles about London and environs, and we shall tell each other all sorts of yarns, so that the conversation doesn’t get too serious.

I believe you readily when you say that you don’t like London. Years ago I felt the same way. It is rather hard for one to get used to the sullen air and the mostly sullen people, to the spirit of aloofness, the class divisions in social life, and life behind closed doors as prescribed by the climate. One must keep down somewhat the animal spirits one acquires on the Continent, one must let the barometer of his joy of life drop from about 760 to 750 milimeters, until one gets gradually accustomed to it. Then, little by little, as one begins to feel at home, one finds that the place has its good sides, too, that the people are, on the whole, more straightforward and reliable than in other places, that no city is better suited than London for scientific research, and that the absence of police chicaneries is also worth something. I know and love Paris but if I were to make a choice, I would prefer to live in London. To really enjoy Paris one must be a Parisian himself, with all the prejudices of the Parisian, with interest primarily in things Parisian, with the conviction that Paris is the center of the world, that it is everything in everything. London is uglier, but still it is more magnificent than Paris; it is the real center of world commerce, and there is also more variety in it than in Paris. At the same time, London allows one to assume an attitude of absolute neutrality to one’s surroundings—which is indispensable for scientific, and even artistic, objectivity. One admires Paris and Vienna, one hates Berlin; with regard to London, however, one maintains an attitude of neutral indifference and objectivity. That also is worth something.

Apropos of Berlin. I am glad that this ill-starred town is finally succeeding in becoming a metropolis. But already Rahel Varnhagen said seventy years ago that in Berlin everything is shabby, and so it seems that Berlin wants to show the world how shabby a metropolis can be. You must send all the Berlinians to their forefathers, conjure up more or less tolerable surroundings and rebuild the place from top to bottom; then you may, perhaps, make something decent out of it. You will hardly succeed, however, as long as that dialect is spoken there.

I have now read The Old and the New,1 for which I send you my hearty thanks. The life of the salt miners is depicted as masterfully as that of the peasants in Stefan.2 Your descriptions of the life of Viennese society are also very fine for the most part. Vienna is indeed the only German city with society; Berlin has only “well-known circles,” and even more unknown ones. That is why Berlin provides material only for novels dealing with literary people, officials and actors. I wonder whether the motivation of the action in this part of your work is not too hasty in parts—you can judge better than I; many things which seem that way to me, may happen quite naturally in a city like Vienna, with its peculiar international character combining the elements of Southern and Eastern Europe. I also find in both parts the usual distinct individualization of the characters: each is a type, but at the same time also a definite individual—a “This One,” as old Hegel would say; and that is as it should be. Still, for the sake of objectivity, I must also find something to object to, and so I come to Arnold. He is really too brave, and when in the end he perishes in a landslide one can associate this with poetic justice, for one is tempted to say: he was too good for this world. It is always bad, however, for the writer to admire his own hero, and it seems to me that toa certain extent you are guilty of this very mistake. In the case of Elsa, there is a certain amount of individuality, although her character is rather idealized; but in the case of Arnold the person is still more submerged in the principle.

The roots for this defect is evident from the novel itself. You obviously felt the need, in writing this book, to take sides openly, to profess your convictions for the whole world to hear. This you have done; it is something you have now left behind and you need not return to this form. I am by no means opposed to tendentious poetry as such. The father of the tragedy, Aeschylus, and the father of the comedy, Aristophanes, were both of them pronouncedly tendentious poets; the same may be said of Dante and Cervantes, and the best feature of Schiller’s Intrigue and Love is that it is the first German tendentious drama. The modern Russians and Norwegians, who produce excellent novels, are all tendentious writers. But in my opinion the tendency must emanate from the situations and actions, without it being stated in so many words; and it is not the writer’s duty to give the reader the future historical solution of the social conflicts which he describes. Moreover, under the present circumstances the novel reaches primarily bourgeois readers, people who do not directly belong to our circles; and in my opinion the Socialist novel fully serves its purpose if, by giving a true portrayal of conditions as they actually are, it shatters the prevailing conventional illusions, shakes the optimism of the bourgeois world and inevitably raises doubts as to the permanence of what exists. The novel thus fulfils its mission even when it does not offer any solution and even, under certain circumstances, when the author ostensibly takes no sides. Your profound knowledge and wonderfully fresh and lively depiction both of the Austrian peasants and of Vienna “society” will find full scope in this kind of novel; and you have already shown in your Stefan that you can treat your heroes with a subtle irony which testifies to the writer’s mastery over his own creation.

Now, I must close with this, for otherwise you may become bored with me. Here everything goes on according to the usual routine…I am busy with my work; Lenchen, Pumps and her husband are going to see a sensational play in the theater tonight; and in the meantime old Europe is getting ready to stir somewhat again, for which the time is gradually arriving. I should but like to hope that it leaves me time to finish the work on Volume III of Capital. After that let it start!

With warm friendship and sincere admiration,

Yours, F. Engels.

LETTER TO FERDINAND LASSALLE

6 Thorncliffe Grove, Manchester May 18, 1858.

Dear Lassalle:

You must have thought it strange that I did not write to you so long, and all the more so since I owed you an answer stating my opinion about your Sickingen. But that is just the reason that has kept me so long from writing. In the present dearth of fine literature I seldom have a chance to read a work like that, and it is years since I have read anything that would induce me to make a detailed analysis and to form a definite and fixed opinion. The trash we get is not worth the trouble. Even the few better English novels which I still get to read from time to time—Thackeray, for instance—could not evoke this kind of interest in me, despite their undeniable literary, cultural and historical significance. Owing to this protracted idleness, my judgment has become blunted, and it would require a long time before I permitted myself to express a definite opinion. Your Sickingen, however, deserves different treatment, and that is why I have taken that time. The first and second readings of your drama, which is, in every sense, as regards material and treatment, a national German drama, stirred me so much that I had to put it away for some time; all the more so since my taste which has grown coarse during these lean years has reduced me to such a state—I must admit it, to my shame—that sometimes even works of slight merit produce a certain effect upon me during the first reading. In order to be quite objective, quite “critical,” I put Sickingen aside, i.e., I let some acquaintances (there still. remain here a few Germans with a literary education, more or less) borrow it from me. Habens sua fata libelli (each book has its fate)—if you let people borrow them, you seldom see the books again, and so it was with difficulty that I recovered my copy of Sickingen. I must tell you that the impression at the third and fourth read ings was the same as at the first; and seeing that your Sickingen can stand criticism, I am giving you my opinion.

I know that I am not complimenting you any too much when I say that none of Germany’s present official poets could write anything like your drama. This is a fact, and one that is but too characteristic of our literature to be overlooked. To turn to the formal side now, I admired the ingenious way in which you develop the plot, and I was pleasantly surprised at the thoroughly dramatic quality of the play. To be sure, you have taken many liberties with the verse; these, however, are more disturbing in reading than they would be on the stage. I should have liked to read the stage version; it is certain that the play in its present form cannot be produced. I discussed it here with a young German poet , (Karl Siebel), who is a countryman and distant relative of mine and knows quite a lot about the stage. He belongs to the Prussian Guard-Reserves, and as such may come to Berlin, for which eventuality I may perhaps take the liberty of giving him a few lines to deliver to you. He liked your drama a great deal, but he thinks that it cannot be produced on account of the long speeches during which only one actor would be busy while the others would have to go through all their gestures two or three times in order not to stand there just as extras. The last two acts prove conclusively that it is not difficult for you to make the dialogue racy and lively; and since it seems to me that, with the exception of a few scenes (which happens in every play), the same could be done in the first two acts too, I have no doubt that in doing the stage version you will give this circumstance proper consideration. The contents and ideas will necessarily suffer thereby, but that is unavoidable; and the complete fusion of the greater profundity and conscious historical content, which you justly attribute to the German drama, with Shakespeare’s vitality and exuberance of action will be achieved only in the future, and perhaps not even by Germans. In that, at all events, I see the future of the drama. Your Sickingen is certainly on the right path; the principal characters are representative of definite classes and trends, and, consequently, represent definite ideas of their times; they are not motivated by petty personal desires, their motives lie in the historical currents by which they are carried along. But you would have achieved greater progress if these motives had been brought out in the course of the action itself, naturally, so to speak, in a living and active manner, so as to obviate more and more the recourse to argued debate (which, incidentally, I read with pleasure, for I found in it your old eloquence displayed before the Assizes or in the Popular Assembly). You yourself seem to make this ideal your goal, for you differentiate between the stage drama and the literary drama; I think that Sickingen could be converted, even though with difficulty (for it is certainly no mean task to achieve) into a stage drama in the indicated sense. Connected with this is the question of character delineation. You are quite right in coming out against the bad individualization prevailing at present, which is confined to smart trivialities and is an essential feature of the vanishing literature of the epigoni. Still, it seems to me that a person is characterized not only by what he does, but also by how he does it. And from this standpoint I believe that no harm would be done to the underlying idea of the drama if the individual characters were more sharply delineated and a clearer line of distinction were drawn between them. The characterization of the Old Man is no longer adequate in our days, and in this respect, I think, you would have profited if you had taken more cognizance of Shakespeare’s contribution to the development of the drama. But these are minor details, which I am mentioning only to show you that I have given thought also to the formal aspects of your drama.

Now, as regards the historical content, you have brought out very graphically the two sides of the movement of those days with which you were directly concerned, and you did it with justified reference to their future development: the national movement of the nobility as represented by Sickingen, and. the humanistic theoretical movement and its further development in the sphere of theology and the Church—namely, the Reformation. In this respect I liked most the scenes between Sickingen and the Emperor, and the one between the legate and the Archbishop of Trier (here you have also succeeded by showing the contrast between the urban legate, with his esthetic and classical education and political and theoretical farsightedness, and the bigoted German clerical prince—in giving strictly individual characterizations, which at the same time follow directly from the representative nature of each of the characters); there is some striking character portrayal also in the scene between Sickingen and Karl. As for Hutten’s autobiography, you are right in describing its contents as essential, but it was certainly a risky thing on your part to incorporate those contents in your drama. I also consider very important the interview in the fifth act between Balthasar and Franz, in which the former explains to his master the really revolutionary policy he should have pursued. It is then that the truly tragic element comes to the fore; and just because this element is so important, it seems to me that you should have indicated it somewhat more strongly in the third act where there are many opportunities for this. But I am again slipping into minor details. The stand taken by the towns and the princes of those times is also depicted in many places with great clarity; thus you practically cover the official elements of the movement of those times. But, it seems to me, you have not sufficiently emphasized the unofficial, the plebeian and peasant elements, as well as their ideological expression. In its own way, the peasant movement was also a national movement, also a movement directed against the princes, just as that of the nobility; and the gigantic dimensions of the struggle which attended it presented a striking contrast to the ease with which the nobility left Sickingen in the lurch, and reverted to its historic vocation of cringing. I therefore think that even with your conception of the drama, which, in my opinion, as you have seen, is somewhat too abstract and not sufficiently realistic, you should have paid closer attention to the peasant movement. The peasant scene with Jost Fritz is indeed characteristic, and the individuality of this “firebrand” is very correctly shown, even though it does not represent with sufficient force the then already rising tide of peasant agitation, as compared with the movement of the nobility. According to my conception of the drama, which insists that one must not forget the realistic because of the ideal, one must not forget Shakespeare because of Schiller, the introduction of the wonderfully colorful plebeian social sphere of those times would have supplied additional material—material of an entirely different kind—to enliven the drama; it would have supplied an inestimable background for the national movement of the nobility which is enacted in the foreground; moreover, it would have placed that movement in its proper light. What an amazing variety of characteristic pictures is provided by this period, which marked the dissolution of the feudal ties among the beggar kings, destitute mercenaries and adventurers of every description—a Falstaffian background which, in this kind of historical drama, would have produced even a greater effect than in Shakespeare’s plays! Apart from this, it seems to me that it is as a result of this very disregard of the peasant movement, that you have been led in a way to misrepresent the national movement of the nobility as well, and at the same time to let the really tragic element of Sickingen’s fate escape you. In my opinion, the mass of the unattached nobility of those times did not think of forming an alliance with the peasants; their dependence on the income derived from the oppression of the peasants would not permit that. An alliance with the cities would have been more of a possibility, but such an alliance did not materialize, or it materialized only partly. The accomplishment of the national revolution of the nobility, however, was possible only in an alliance with the cities and the peasants, especially with the latter; and that, in my opinion, was precisely ‘what constituted the tragic element—the fact that this fundamental condition, an alliance with the peasants, was impossible; that the policy of the nobility necessarily had to be a narrow one; that at the very moment it was prepared to assume the leadership in the national movement, the bulk of the nation— the peasants—protested against its leadership, and as a result, it was doomed to failure. I cannot judge to what extent your assumption that Sickingen actually maintained some contact with the peasants is historically correct. But that is not the point. Hutten’s writings, as far as I can remember, touch but lightly on the ticklish point of the nobility, and they seek to direct the anger of the peasants primarily against the priests. But I do not want by any means to dispute your right to conceive of Sickingen and Hutten as of men who intended to emancipate the peasants. At the same time, however, you also had before you the tragic contradiction in the position of these two men, placed as they were, on the one hand, between the nobility which was decidedly opposed to the emancipation of the peasants, and the peasants themselves, on the other hand. Here, in my opinion, lay the source of the tragic collision between the historically necessary postulate and the impossibility of accomplishing it in practice. By leaving out that factor, you have reduced the scope of the tragic conflict to the fact that instead of dealing directly with the emperor and his functionaries, Sickingen dealt only with one prince (although here, too, you show proper tact in introducing the peasants), and you let him perish merely on account of the cowardice of the nobility. This cowardice, however, would have been more fully motivated if there had been more stress on the rumblings of the peasant movement and on the fact that the sentiments of the nobility had grown conservative as a result of the previous peasant rebellions and the “Poor Conrad” movement. In point of fact, this is but one way through which the peasant and plebeian movement could be introduced into the drama, and there are at least ten other possible ways which are just as good or better.

As you see, I am judging your work, both from the esthetic and from the historical aspect, by a very high standard—namely, the highest; and the fact that I must do so in order to offer an objection here and there, is the best proof of my high opinion of your work. It has been many years that, in the interests of the Party itself, criticism among us is necessarily expressed as frankly as possible; for all that, however, it is a cause for rejoicing to me and to all of us when we have additional proof of the fact that, whatever the sphere of endeavor, our Party always shows its capacity for penetration. That is what you have done in this case, too.

NOTES

1. Minna Kautsky’s novel Die Alten und die Neuen appeared in the social-democratic magazine Neue Welt in 1884.—Ed.

2. Stefan von Grillenhof, a novel by the same writer.—Ed.

Literature of the World Revolution/International Literature was the journal of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers, founded in 1927, that began publishing in the aftermath of 1931’s international conference of revolutionary writers held in Kharkov, Ukraine. Produced in Moscow in Russian, German, English, and French, the name changed to International Literature in 1932. In 1935 and the Popular Front, the Writers for the Defense of Culture became the sponsoring organization. It published until 1945 and hosted the most important Communist writers and critics of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/literature/international-literature/1940-n11-12-IL.pdf