Marx’s knowledge and appreciation of Shakespeare’s plays was unbounded, with the whole Marx clan deeply immersed in the world of his stories. Jenny Marx wrote reviews of Shakespeare productions, all the children learned them, Eleanor acted in them, the whole family spoke to each other in reference to his words, even took on nicknames of characters. Along with a look at Shakespeare in Marx’s Capital, Nechinka also introduces other authors in Marx’s vast literary allusions to appear in his writings.

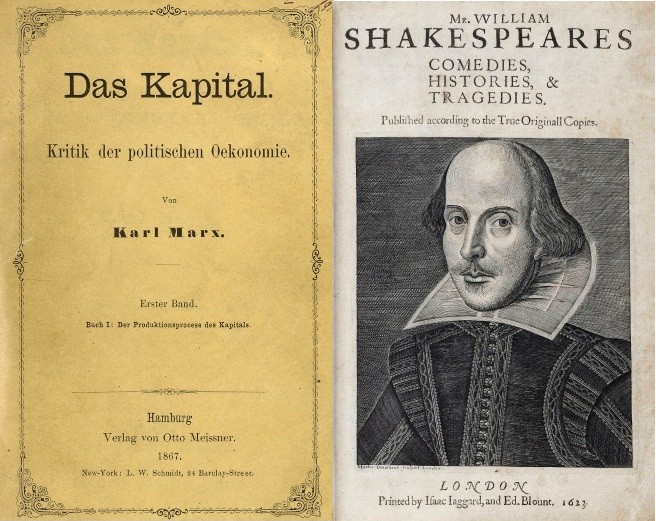

‘Shakespeare in Marx’s ‘Capital’’ by M. Nechkina from International Literature. No. 3. 1935.

Shakespeare does not appear very often in Capital but the relative rareness of the occasions on which he does appear emphasizes their significance.

Marx counted Shakespeare among his strongest literary attachments. He had a thorough knowledge of him and had several times read his works completely: Shakespeare was equally loved in Marx’s family. “The children are always reading Shakespeare,” Marx wrote to Engels in a letter of April 10, 1856. Shakespeare’s characters had made such a thorough impression on him that they came easily to his mind and it came natural for him to use them as illustrations. Marx’s daughters used to give their acquaintances nicknames using the names of Shakespeare’s heroes. Marx himself did the same, using chiefly the names of the comic type of hero. Marx’s use of the character of Falstaff is extremely interesting. It is safe to say that the analysis of this character in Marxist literary research cannot but lose a great deal if the corresponding places in Marx’s works are overlooked. Falstaff for Marx was a kind of “personified capital” of the epoch of the dawn of capitalism, which gave birth to the bourgeois of the epoch of primitive accumulation. An unpardonable liar, a narrow pleasure seeker, thinking only of his own material interests, a dissolute rake openly showing his contempt for all the religious mummery of feudalism, a highwayman and yet at the same time an arrant coward, a swindler and merry wine-bibber, readily to sell all his knightly virtues for a pound note—Falstaff is a clearcut type of the epoch of primitive accumulation. The fragments of feudal ideas are merely the building material for his new bourgeois morality. Saving his own skin by wile in the middle of the battle, (Falstaff, one will remember, threw his sword on the ground at the first advance of the enemy and pretended to be dead, he argues that to save one’s own life is the first knightly virtue. Plundering, seizing, stealing, borrowing without repaying while swearing to the contrary, calling upon the Virgin Mary and all the mediaeval saints are amongst Falstaff’s favorite tricks, Shakespeare, regretfully watching the downfall of the feudal world, showed his rejection of the coming bourgeois world in the comic character of Falstaff.1

In his letters Marx makes a comparison between Falstaff and Herr Vogt, Napoleon III’s agent, whom he shows up and ridicules in a famous pamphlet. Falstaff also appears in Capital, but about that later. Falstaff figures not only in Marx’s correspondence and in Capital but also in other works. In his article “Moralising Critique and Critical Morality” directed against the philistine Karl Heinsen, Marx ridicules the latter’s assertion that monarchies are the chief cause of misfortune and poverty. Making fun of Heinsen’s arguments, he remarks that the slavery of the Southern States of the American Republic, which flourishes without any monarchic forms, might agree with Falstaff in wishing that such arguments were as cheap as blackberries. We frequently come across other Shakespearian imagery. In his Eighteenth Brumaire Marx speaks of his “hero” in the following words: “An old and crafty roué he regards the historical life of the nations as a comedy in the most ordinary sense of the term, looks upon their most important activities, their actions of State, as a masquerade in which the fine costumes, the high sounding words, and the dignified postures are nothing but a mask for trifling. Thus it was in the Strassburg affair (1836) when a tame Swiss vulture impersonated the Napoleonic eagle. When he raided Boulogne (1840) he had some London footmen decked out in French uniforms; they represented the army. In his Society of December the Tenth, he got together about ten thousand loafers and tatterdemalions to play the people, as Snug the joiner played the Lion.” The same lion, on another occasion is referred to by Marx in a similar illustration. In his Critique of Philosophy criticising Hegel’s conception of governmental authority Marx likens the different aspects of the Hegelian conception to the lion in A Midsummer Night’s Dream when it cries out:

Then know that I one Snug the joiner am

A lion fell, nor else no lion’s dam

For, if I should as lion come in strife

Into this place, it were pity on my life.

and he points out that you either have here the lion of contrast or the Snug of misrepresentation.

In the same article Marx invites Heineen to look closer at the type of Ajax in Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida and quotes the long dialogue between Achilles and Thersites. Marx alluded to this dialogue in 1864 when he was so disgusted with Garibaldi for fraternizing with Palmerston at the very moment when the congress of revolutionaries in Brussels was putting its hopes on him as leader of the revolution and quoted the words of Thersites at the end of the dialogue: “I had rather be a tick in a sheep than such a valiant ignorance.” (Troilus and Cressida, Act III, Scene III)

Marx made an interesting remark about Shakespeare as a historian. In 1861 Marx “as a holiday” read through in the Greek original The Civil Wars in Rome by the ancient historian Appian, and in a letter to Engels dated February 27, expressed the view that Appian tries to dig down to the material basis of the civil wars. This historian awarded the laurel to Pompey as a military strategist, and Marx agreeing with this view, says in his letter that he thought Shakespeare must have had some idea in his mind of what Pompey was actually like when he wrote his comedy Love’s Labour Lost.

We may add here that Engels also was a great admirer and student of Shakespeare. In one of his early works, for instance, in an article entitled “Landschaften,” published in 1840 in the Telegraph fur Deutschland, he wrote the following lines: “What marvelous poesy is hidden in the provinces of Britain. It often seems as though one were living in the golden age of Merry England, and that you have only to look round and you will see Shakespeare with a gun over his shoulder, hiding in the bushes while out for other people’s game, or you are surprised that on that green meadow there is not being enacted in flesh and blood one of his divine comedies. For wherever the scene of his plays is laid, in Italy, in France, in Navarre—it is really all the time Merry England that we see before us, the homeland of his delightful common people, his philosophizing school teachers, his charming and strange women. In every instance one realises that the action could only take place under English skies, for instance in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, one feels the influence of the South and its climate in the characters of the play as strongly as one does in Romeo and Juliet.”

And in a letter written on September 26, 1847 Engels advises Marx to read an article by O’Connor, which he says reminds one of Shakespeare.

It is a very great thing to be able to make use of the artistic imagery of world literature in a scientific work. If we follow in what way and on what occasions Shakespeare appears in Capital, we shall see the significance of the explanatory Shakespearian allusions in the surrounding economic context.

The first Shakespearian character that appears in Capital is a comic one, Widow Quickly, Falstaff’s friend, appears in the first chapter dealing with value. Mistress Quickly, as everyone knows, the landlady of a tavern and very fond of drinking, is an exceedingly merry widow. Mistress Quickly is a frequently recurring figure in Shakespeare’s works; she appears in both parts of Henry IV, in Henry V (1st part) and in the Merry Wives of Windsor. She is everywhere game for a fight, she is a gossip, a shameless hussy and ready chatterbox with a keen sense of the value of money, ready to do anything she is asked to do, for a price.

Mistress Quickly appears in the first chapter of Capital which deals with the analysis of commodities. Marx speaks of the substance of value and leads the reader to his famous conclusion about not a single atom of the natural substance of a commodity entering into the substance of its value. Leading up to this extremely important and difficult conclusion, Marx amuses the reader with the remark “the reality of the value of commodities differs in this respect from Dame Quickly, that we don’t know ‘where to have it.’ The value of commodities is the very opposite to the coarse materiality of their substance, not an atom of matter enters into its composition.” This could hardly have been said of Mistress Quickly, about whom one could say that she was “to be had” in London, in Eastcheap at the Boars’ Head Tavern, and moreover that she was to be found in extremely close association with Falstaff to whom she cries, after one of their regular drinking bouts:

“Well, fare thee well; I have known thee these twenty nine years come peascod time; but an honester and truer hearted man, well fare thee well.”

In the first chapter of Capital, the chapter on commodities, the analysis of the commodity form is brought to an end with a very important question, that of the interrelation of the material properties of a commodity, the use value and the exchange value. At the moment where the explanation is given Shakespeare again makes his appearance.”

“So far no chemist ‘has ever discovered exchange value either in a pearl or a diamond. The economical discoverers of this chemical element, who by-the-bye lay special claim to critical acumen, find however that the use-value of objects belongs to them independently of their material properties, while their value, on the other hand, forms a part of them as objects. What confirms them in this view, is the peculiar circumstances that the use value of objects is realised without exchange, by means of a direct relation between the objects and man, while on the other hand, their value is realised only by exchange, that is by means of a social process. Who fails here to call to mind good friend Dogberry, who informs neighbour Seacoal that ‘To be a well favoured man is the gift of fortune but reading and writing comes by nature.’”

The conversation between the watchmen in Much Ado About Nothing, it may be here remarked is one of Shakespeare’s most successful comic scenes. It has an important place in the composition of the play. Just before it a tense and tragic scene has come to an end: Don Juan comes into Leonato’s room and tells Claudius about his sweetheart Hero’s unfaithfulness. This false news underlies the intrigue of the comedy. Claudius is in despair, Don Juan undertakes to prove to him the truth of the terrible news. After this the third scene of the third act gives comic relief: The good-natured Dogberry is giving the night watchmen instructions, advising them not to have anything to do with thieves, and therefore not hold up or detain suspicious characters without first obtaining the latters’ permission, in other words giving them to understand by his explanations, that there is nothing really for watchmen to do at all.

It is in the same dialogue between the watchmen that Dogberry’s saying quoted by Marx about good looks and the ability to read and write occurs.

After twice resorting to Shakespeare for an explanation of the theory of value, Marx also has recourse to him in the second chapter, the one on Exchange. And here Shakespeare is called upon for the explanation of a very important proposition concerning a factor in the historical development of the importance of money.

“With the expansion of commodity circulation there is an increase in the power of money, that absolute social form of wealth, always ready at beck and call. Everything becomes saleable and buyable. Circulation becomes the great social retort, into which everything is drawn, to come out again as a gold crystal.”

This idea is illustrated by a passage from Shakespeare’s famous tragedy Timon of Athens, one of his essentially philosophical works. The tragedy deals with the power of gold over men. Both Coleridge and Schiller were very keen on it and thought it ought to be adapted for the German stage. In Act IV Scene III Shakespeare puts into the mouth of Timon of Athens the famous monologue about the power of gold. The dramatic situation is as follows: Abandoned and ridiculed by his friends who had had benefits heaped upon them while he had been wealthy, but who hand him over to ridicule now that his wealth has been exhausted, Timon shakes the dust of Athens from his feet and seeks refuge in a cave in the forest near the sea. In order to stay his hunger he seeks roots for food and begins digging the ground. Suddenly he comes upon a treasure, whereupon he speaks the following monologue. The passages omitted by Marx are put in brackets:

(What is here?)

Gold? yellow, glittering, precious gold? (No gods

I am no idle votarist. Roots, you clear heaven.)

Thus much of this will make black white: foul—fair;

Wrong—right; base—noble; old—young; coward—valiant.

Ha, you gods. Why this? What this, you gods? Why this

Will lug your priests and servants from your sides;

Pluck stout men’s pillows from below their heads

This yellow slave

Will knit and break religions; bless the accurs’d

Make the hoar leprosy adored; place thieves

And give them title, knee, and approbation,

With senators of the bench; this is it

That makes the wappened widow wed again;

(She whom the spital-house and ulcerous sores

Would cast the gorge at, this embalms and spices

To the April day again.) Come, damned earth,

Thou common whore of mankind…

The origin of surplus value is shown, the predatory nature of wages under capitalism disclosed,—and in the chapter about the working day, in dealing with the exploitation of children, Marx again has recourse to Shakespeare. The proletariat protested against the “Law” of the exploiters, whereby eight to thirteen year old children worked to breaking point on an equal footing with adult workers. But “capital” answered

My deeds upon my head! I crave the law

The penalty and forfeit of my bond.

These were the words of Shylock in The Merchant of Venice. Shylock had the right to cut from Antonio’s breast a pound of flesh in the event of the latter being unable to pay his debt. The words quoted by Marx were spoken by Shylock in answer to the reminder given by Portia, the judge, that the usurer, as a human being, should show mercy.

Portia:…I have spoke thus much

To mitigate the justice of thy plea,

Which if thou follow, this strict court of Venice

Must needs give sentence ’gainst the merchant there.

Shylock: My deeds upon my head! I crave the law

The penalty and forfeit of my bond.

Continuing in a tense court scene, when the judges have been convinced that nothing will move Shylock, Portia, dressed as a judge, pronounces sentence:

Portia: Why then thus it is:—

You must prepare your bosom for his knife.

Shylock: O noble judge: O excellent young man!

Portia: For the intent and purpose of the law

Hath full relation to the penalty,

Which here appeareth due upon the bond.

Shylock: ’Tis very true. O wise and upright judge!

How much more elder art thou than thy looks!

Portia: Therefore lay bare your bosom.

Shylock: Ay his breast;

So says the bond: doth it not, noble judge?

Nearest his heart: those are the very words.

Marx in continuing his account of the exploitation of children, recalls the words of Shylock. He writes:

“the lynx eye of capital discovered that the law of 1844 did not allow five hours’ work before midday without a pause of at least 30 minutes for refreshment, but prescribed nothing of the kind for work after mid-day. Therefore, it claimed and obtained the enjoyment not only of making children of eight drudge without intermission from 2 to 8:30 p.m. but also of making them hunger during that time;

Aye his heart

So says the bond.

“This Shylock-clinging to the letter of the law of 1844, so far as it regulated children’s labour, was but to lead up to an open revolt against the same law as far as it regulated the labour of ‘young persons and women.’”

Goethe, another poet beloved by Marx, is also quoted a number of times in Capital. He appears in the first chapter (On Commodities). Incidentally the fact is interesting that while Marx borrows vivid imagery from Shakespeare, from Goethe in most cases he takes philosophical generalisations which have been compressed into verse by the poet. Marx criticises the petty bourgeois attempt to remove the inconveniences resulting from this character of commodities not being directly exchangeable and then goes on to say: “Proudhon’s socialism is a working out of this Philistine Utopia, a form of socialism, which, as I have elsewhere shown, does not possess even the merit of originality. Long before his time the task was attempted with much better success by Gray, Bray and others. But for all that wisdom of this kind flourishes even now in certain circles under the name of ‘science.’ Never, has any school played more tricks with the word science than that of Proudhon, for

“Wo die Begriffe fehlen

Da stellt zur rechten Zeit ein Wort sich ein’

(When concepts flag,

In nick of time come words to fill the gap.)

“These words of Faust’s do certainly very aptly apply to the Proudhon school. Faust also figures in the part about the process of exchange, with his exclamation Im Anfang war der Tat.” (In the beginning was the deed.)”

In the chapter on so-called primitive accumulation Marx says, criticising Thiers’ attacks on socialism:

“But as soon as the question of property crops up, it becomes a sacred duty to proclaim the intellectual food of the infant as the one thing fit for all ages find for all states of development.”

And here he appeals further to Goethe where the latter ridicules the same attitude in the following dialogue:—

Teacher: Think child where do all these riches come from. Out of itself nothing can ‘come.

Child: Yes I got everything from father.

Teacher: But where did father get them from?

Child: From grandfather.

Teacher: No that can’t be. Otherwise where did grandfather get them from.

Child: He just took them.

The same quotation occurs in Engels “German Socialism in Poetry and Prose.”

Tracing the conversion of surplus value into capital, Marx says: “While the capitalist of the classical type brands individual consumption as a sin against his function, and as ‘abstinence’ from accumulating, the modernized capitalist is capable of looking upon accumulation as ‘abstinence’ from pleasure.”

Here again he quotes Goethe:—

Two souls, alas, do dwell within his breast

The one is ever parting from the other.

substituting the word “his” for “the” of the original.

One could give a very great many instances of Marx’s use of world literature in Capital. Marx quotes Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Dante’s Divine Comedy, Maliére, his beloved Heine and ancient writers, all of whom Marx knew in the original; Sophocles, Homer, Aeschylus and Horace. He also makes use of the art of the people in the form of sayings and legends and in particular the legend of the pied piper.

Sophocles, like Shakespeare, is called upon by Marx not only as a literary helpmeet but also as a witness of his age. His words not only illustrate but also are evidence in support of the proposition which is being demonstrated:

“But money itself is a commodity, an external object, capable of becoming the private property of any individual. This social power becomes the private power of private persons. The ancients therefore denounced money as subversive of the economical and moral order of things.”

In support of this he quotes Antigone:—

“Money is an evil for mortal men. For money cities are doomed to fall. For money the exile leaves his father’s roof. Money it is that corrupts innocent hearts, turns them to evil ways, deceitful wiles and ail dishonesty.”

In the chapter on the general law of capitalist accumulation, a chapter which is fraught with bitter class indignation, the mighty figure of Prometheus is borrowed from Aeschylus. The worker is bound to Capital just as Prometheus is bound to the rock by Vulcan:—

“The law, finally, that always equilibrates the relative surplus-population, or industrial reserve army, to the extent and energy of accumulation, this law rivets the labourer to Capital more firmly than the wedges of Vulcan did Prometheus to the rock. It establishes an accumulation of capital. Accumulation of wealth at one pole is, therefore, at the same time, accumulation of misery, corresponding with accumulation of capital. Accumulation of wealth at one pole is, therefore, at the same time accumulation of misery, agony of toil, slavery, ignorance, brutality, mental degradation, at the opposite pole, i.e., on the side of the class that produces its own product in the form of capital.”

The ancient Homer and his poetical imagery appear on the pages of the chapter about the working day. The victims of capitalist exploitation rise up before Marx like live people. They walk out of the pages of the papers he has just been reading, the stories he has just heard, the grim every day realities of capitalist Europe of the sixties. Their images stand before Marx with hallucinatory clearness when he writes this chapter; they pass before his sight, they hold blue books under their arms, the books in which are expressed the laws of capitalism which are leading them to their death.

The Cyclops iron Foundries—this by association brings to mind the famous monsters of the Odyssey and Marx makes a play upon the words, saying that to forbid the working of children during the night time was beyond “the powers of Messrs. Cyclops.

One last example. On the pages of Capital interlaced with complicated theoretical conclusions, more familiar figures appear; the bony Rossinani, carrying his tall emaciated knight with the fat round Sancho Panza beside them. Don Quixote is introduced by Marx in explaining an important point in his theory of scientific socialism, the question of the historicity of social economic formations, the question of the complex ideological superstructures inherent in any given formation and bound up with definite social relationships. In this connection he remarks that Don Quixote had to pay dear for his error in thinking that knight errancy was equally compatible with all economic forms of society.

Translated from the Russian by N. Goold-Verschoyle

1. The editors consider this statement quite incorrect. Shakespeare was an artist not of the feudal aristocracy but of the aristocracy that was becoming capitalist. He tried to take all that was best in the bourgeoisie for his class (the characters of Portia and Antonio in The Merchant of Venice). In a number of plays he critised feudalism very severely (Romeo and Juliet, King Lear and others).

His Merry Wives of Windsor makes fun of Falstaff, shutting him up in a basket with a lot of dirty linen, he is thrown into a foul reach of the Thames. Falstaff is struck in the mouth when he dresses up as a fat godmother. Falstaff is as fat as a tub, his belly prevents him from seeing his own knees. Finally in Henry V he dies ignominiously in Mistress Quickly’s arms. But in spite of this the historic future is with Falstaff. The Falstaffs of industrial capital have only become slightly thinner, have put what they have plundered into circulation, have learnt better how to calculate and squeeze out surplus value.

Literature of the World Revolution/International Literature was the journal of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers, founded in 1927, that began publishing in the aftermath of 1931’s international conference of revolutionary writers held in Kharkov, Ukraine. Produced in Moscow in Russian, German, English, and French, the name changed to International Literature in 1932. In 1935 and the Popular Front, the Writers for the Defense of Culture became the sponsoring organization. It published until 1945 and hosted the most important Communist writers and critics of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/literature/international-literature/1935-n03-IL.pdf