A fantastic history and analysis of the historic Black U.S. press from former ‘Crusader’ editor Cyril V. Briggs.

‘The Negro Press as a Class Weapon’ by Cyril V. Briggs from The Communist. Vol. 8 No. 8. August, 1929.

In our general underestimation of the revolutionary role of the Negro workers, we are inclined to overlook the importance of the Negro press. This would be one of the worst blunders we could commit.

In order to win the Negro masses for the revolutionary overthrow of the vicious system under which they are lynched and jim-crowed and victimized in a thousand ways, it is necessary that the Communist Party should have a full appreciation and understanding of the various factors influencing the Negro masses today. Some of these influences, like religion, we will have to fight without quarter. Others, like the Negro press, we will be able to utilize in our campaigns against lynching and other forms of white ruling class terrorism, segregation and high rents, disfranchisement, discrimination in the A.F. of L. unions and on the jobs, and for the full political, social and racial equality of the Negro.

Until recently the existence of an influential Negro press was virtually unknown to both the white ruling class and the white masses. Manifestly the existence of a powerful Negro press, uninfluenced and uncensored, unknown to the capitalist class, was of the utmost danger to that class and Ray Stannard Baker, writing in World’s Work some years ago, obligingly warned of this danger:

“Few people realize that there are more than 450 newspapers and other publications in America devoted exclusively to the interests of the colored people, nearly all edited by Negroes…The utter ignorance of the great mass of white Americans as to what is really going on among the colored people of the country is appalling—and dangerous,.”

These periodicals are published throughout the country—nearly every Negro urban center has one or more. Of the 450, 83 are religious, official organs of some denomination, or private organs of ambitious peddlers of religious bunk, 45 are accredited as journals of fraternal orders; 80 are school and college periodicals, 31 are magazines, and something like 250 are general newspapers Most of the newspapers are weekly. There are no dailies, although there have been some attempts to publish daily papers. Marcus Garvey a few years ago tried publishing a daily. There was also a more ambitious attempt in Baltimore where a daily paper, the Daily Herald, was actually published for over two years. The Negro press has an estimated circulation of over 1,500,000. As each copy of a newspaper or magazine is read by more than one person the influence of the Negro Press is greater than indicated by mere figures of circulation. In some parts of the South and the West Indies, the more militant papers and magazines published in the North are passed around until each copy is read by twenty or more persons. Especially is this so where the paper in question has been barred by the local authorities and has to be smuggled in. In one instance on record, one copy had been read by over one hundred workers.

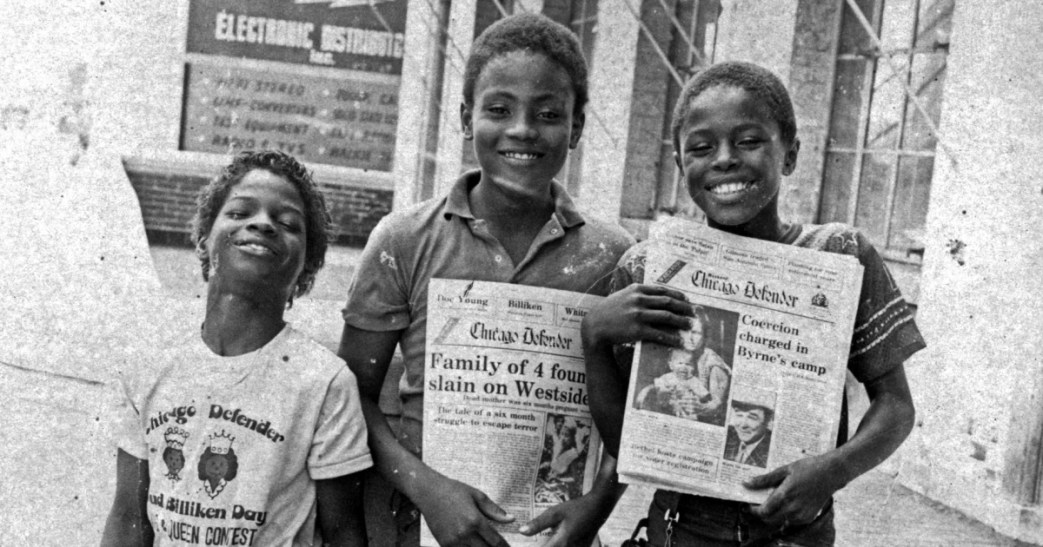

In seeking to evaluate the circulation and influence of the Negro press it would be useless to make comparisons with any other section of the American press, although the language press would come nearest to affording a comparison, but even here it would not be altogether fair, since the latter has a monopoly in its field not enjoyed by the Negro press. Moreover, it must be remembered the foreign-born groups are large, compact masses of city dwellers while the Negroes are distributed over a wide geographical area, and are handicapped by poverty, rural isolation and illiteracy. Com- pared with the press of a minority group, however, the result is illuminating—the Negro press must, as a rule, get along without being subsidized. It is only recently that national advertisers have begun to use its columns and this only to a small extent since, significantly, the Negro press is still regarded by the capitalists as too much of a class press. Recently, too, the power of the rising Negro bourgeoisie has begun to make itself felt in the policies and management of the Negro press. So far, this latter influence is mostly confined to the papers in such large cities as New York, Chicago, Pittsburgh. It is no accident that such papers as the Chicago Defender, the New York Amsterdam News, the New York Age, the Pittsburgh Courier, the Baltimore Afro-American, the Atlanta Independent, etc., are the first to give expression to the growing power of the Negro bourgeoisie. ‘These papers are published in the big industrial and mercantile centers where the Negro bourgeoisie is concentrated. However, while tending toward economic conservatism these papers, with the exception of the New York Age, and the Atlanta, Independent, which are hopelessly reactionary, still retain a large measure of militancy on racial demands. Of this group, which accounts for probably one-third of the circulation of the Negro press and is the most powerful, the Baltimore Afro-American is the least reactionary Less important in power and influence is the numerically larger group of small town papers scattered throughout the country, especially throughout the South. This group carries on a precarious existence and its editors are closer to the economic struggles of the masses. While not clearly realizing the class implications of the Negro liberation struggle, the editors of this group are much more open to revolutionary ideas than are those of the first group. They also reach a larger mass of readers. However, it is the first and smaller group that reaches and influences the Negro proletariat in the large northern industrial centers, and therein lies its importance for us.

That the white ruling class of the South fears the influence of the Negro press on the oppressed Negro masses is evident by its bitter hostility to Negro newspapers, and particularly to those published in the North. In many sections of the South, the harshest measures have been adopted against Negro papers and those who circulate them. Negroes known to be agents of Northern Negro papers have been actually lynched in many parts of the South. The more outspoken periodicals are heartily execrated among the white ruling class.

In 1919 the same fear gripped the Federal Department of Justice when the Attorney-General included the Negro magazines and newspapers in his investigation. “Neither is the influence of the Negro Press in general to be reckoned with lightly,” he warned the Senate.

Phenomenal progress in news getting, in make-up, in quality of articles and editorials, has featured the history of the Negro press within recent years. From a group of poorly made-up, atrociously edited periodicals, the Negro press has improved so greatly that today it stands comparison with any other group of periodicals. It is served by several efficient news services, including the Associated Negro Press, the Preston News, the Capital News Service, and the radical Crusader News Service. In addition, several of the bigger papers have their own correspondents in the large cities. Articles range from local to national politics, and frequently there are articles on Africa, the West Indies, Brazil, etc. Occasionally there is a good cartoon, though generally the Negro press lags in this department. An analysis of forty typical periodicals revealed that three-fifths of the articles are devoted to the characteristic struggles of the race, the fight against lynching, against disfranchisement, segregation, etc. The space devoted to news and opinion approximated 60 per cent., with only those papers published in the big cities carrying sport and theatrical departments and magazine features.

While the tone of the Negro press in general is one of struggle, there exists great confusion as to the methods of prosecuting that struggle, arising out of the failure to understand the class basis of Negro oppression. Take for instance the following example of failure to understand the role of the capitalist state as an instrument of oppression against both the white and the black workers. It is from the Mobile Weekly Press:

“…and we reassert that the government is all right, but the people are wrong, and cause the world ofttimes to denounce our form of government for its failure to protect its citizens at home…Our government is all right, but the people are wrong, and we speak of the people and not of the government.”

This quotation is typical of the confused attitude of the bulk of the Negro press on the source and causes of Negro oppression in America and elsewhere. Of the several hundred newspapers only one, the Negro Champion, correctly points out the source and causes of Negro oppression and militantly calls the Negro workers to effective means of struggle. Of the several news services, the Crusader News Service is the only one interested in presenting the news from a labor point of view and in educating the Negro masses on the source of their oppression. The Crusader News Service has a wide influence, particularly among the small town newspapers.

The Negro press has a revolutionary past which still, in large measure, motivates its present. Taking its start from a situation of conflict, it has carried through its entire history the motive of the fight for liberation.

Even while sunk in slavery the Negro realized the need for a press to agitate his wrongs. That militant and fearless opponent of the slave power, Frederick Douglas, with other free Negroes responded to this need—Douglas with the North Star, later changed to Frederick Douglas Paper; Samuel Cornish and John B. Russwun with Freedom’s Journal. This latter was the first Negro periodical to appear in the United States. Its name was later changed to Rights to All. Then there were others, their titles expressive for the most part of the struggle they waged against the monstrous system of chattel slavery; Mirror of Liberty, the Elevator, the Clarion, the Genius of Freedom, the Alienated American, the Ram’s Horn, the Colored American, etc.

That even in those dark days of human slavery the influence of the reformist was present in the ranks of the oppressed is gathered from the declaration of objects of the Colored American:

“Its objects are . . . the moral, social and political elevation and improvement of the free colored people; and the peaceful emancipation of the enslaved.”

On the other hand, it was the Negro press of that period which paved the way for the bold attempts of Nat Turner, Denmark Vesey and other Negro revolutionaries who, inspired by the daring deeds of Toussaint L’Ouverture and the revolutionary ideas of the French Revolution, organized the many slave insurrections which gave so much concern to the slave power, several times bringing it to the verge of complete demoralization.

The reaction of the slave-holding South to the influence of the Negro press was one of brutal terrorism against any person caught with copies of these papers. Even in the North there was brutal hounding and repression of Negro editors. Douglas’ home was burned to the ground, following the suggestion by the New York Herald that that fearless Negro agitator should be exiled to Canada and his printing presses dumped in the lake.

However, no Negro publication in those dark days of slavery came in for so much execration on the part of the slave-holding South and its sympathizers in the North as Walker’s famous Appeal —not a newspaper but a pamphlet that appeared in several editions. Walker was a free Negro from North Carolina, who, in 1827, opened a second-hand clothing store in Boston which he used as a blind for his revolutionary activities. The reaction of the slave holders to Walker’s pamphlet is the best tribute to the ability and fearlessness of the writer. As far South as Louisiana men were imprisoned for having it in their possession; the mayor of Savannah demanded of the Mayor of Boston that he punish the author, to which the latter flunky replied expressing regret and disapproval of the work.

The close of the Civil War saw a flood of pamphlet literature and new newspapers.

That the Negro press has brought down to the present period its tradition of struggle is seen in the demand, almost general up to a few years ago and still sufficiently widespread to be of tremendous import, for armed resistance to lynching.

The Negro press was a constant source of annoyance and concern to the white ruling class during the World War. Bearing in mind the brutal system of exploitation and terrorism to which this class has submitted the Negro masses it was no wonder that the white ruling class saw the specter of revolution lurking behind the demands of the Negro press for the abolition of lynching, discrimination, etc. The usual trick of buying up the leaders was resorted to. Emmet J. Scott was made special assistant to the secretary of War in “the matter of the welfare and morale of the colored people”, conferences of editors were held in Washington; war propaganda was mailed regularly to the Negro press; a Speakers Committee of one hundred was organized; Du Bois, until then one of the most outspoken critics of America’s treatment of the Negro, was promised a captaincy and betrayed the Negro masses with his infamous “Close Ranks” editorial, in which he called upon the Negroes to forget their grievances, and unite with their oppressors against the latter’s enemies. Scott, later had the temerity to boast of his work in lining up the Negro editors for the betrayal of their race:

“Our editors were conservative on all current questions, at no sacrifice of courage (sic) and absolute frankness in the upholding of principles….’

That there were editors who found it impossible to be “conservative on current questions,” in which was included the burning question of the lynching of black men and women (during the war there was one particularly revolting case of the lynching of a pregnant woman and the ripping from her womb of the unborn babe which was immediately stamped to death under the feet of her brutal murderers) by the bestial southern white ruling class at the very moment when black soldiers were fighting on the western front, that there were such editors is evident from the proposal of the Attorney-General to suppress the Chicago Defender, and the Crusader—a proposal which was abandoned by reason of the fear of the reaction of the Negro masses. There were other papers, too, that caused grave concern to the government.

The Amsterdam News of February 27, 1918, commenting editorially on the lynching by a Tennessee mob of Jim MclIlherron on February 22, for the “crime” of self-defense, said in part.

“And ’tis to protect these fiends of hell that thousands of our best blood have been sent to France! This is our reward! Our taste of democracy! Relic of the Past and earnest of the Future!”

The question of self-determination for the American Negro raised by this paper during the World War:

“…have we not as much right as the Poles and Slavs to aspire to a free independent existence under which can be guaranteed and enjoyed ‘security of life,’ equal opportunities and unhampered development. And where are our leaders? Are their mouths stopped with the white man’s gold that they can do nothing but mumble out advice to be patient and await a crazily conceived, absolutely unprecedented ‘peaceful solution.’…? Are they traitors or fools? Bought or untaught?

And again on January 2, 1918, in an editorial “Democracy and the Colored Race: the Case for Autonomy”, this paper agitated for a free Africa and for self-determination in the Southern United States, pointedly asking:

“Can America demand that Germany give up her Poles, and Austria her slavs, while America still holds in the harshest possible bondage a nation of over ten million people, who occupy in the majority several of the Southern States and to whose industry is solely due the prosperity of the Gulf States and the fact that they are today prosperous and productive communities and not roaring wildernesses.”

With the return of the Negro soldiers and the occurrence of race riots in Washington, in Chicago, in Knoxville, etc., the attitude of the Negro press became so aggressive and potentially revolutionary that the government again experienced serious concern, and at least one Congressman voiced the opinion that certain Negro editors should be hung because of the open encouragement they gave to the spirit of armed resistance with which the Negro soldiers returned to their homes. Not only radical publications like the Crusader and the Messenger gave open encouragement to this spirit of armed resistance, but papers like the Cleveland Gazette carried articles with headlines like the following (from the Cleveland Gazette): Springfield Riot Truth—the first time given to the Public by any Publication—Veterans of the World War were on the Job and Our People Were Ready—Chicago and Washington Their Precedent.”

As and when the Communist Party of the U.S.A. carries out the decisions of the Comintern in reference to leading the struggles of the Negro masses against lynching and other forms of white ruling class terrorism, against jim-crowism, against segregation and its resultant high rents, against discrimination in the old trade unions, etc., we will find very little difficulty in getting our activities chronicled in the columns of the majority of Negro periodicals, providing, of course, we have an alert and up-to-date press service. As the Sixth World Congress Resolution on the Negro Question points out the oppressed, Negro masses are naturally skeptical of all white people. It is the task of the Communist Party of the U.S.A. to prove effectively to the Negro masses that the Communist Party is the party of all the workers, of black and white alike. This we can do only by increasingly participating in the racial struggles of the Negro masses as well as in their economic struggles, and by obeying the decisions of the Comintern to push the Negro workers forward, both in the Party and in the unions we control.

In our work among the Negro masses, we must at all times have effective contact with the Negro press, which, by the nature of its own struggle must be more or less sympathetic to us. For this purpose we need an up-to-date press service. The present press service, while exercising a wide influence, is not good enough. We are under the necessity of working fast, as with the growth of the Negro bourgeoisie more and more papers will come under its control with the result that their columns will be closed to our propaganda. We must immediately increase the effectiveness of our press service. At present, the work of preparing the weekly releases is left to one comrade, who has many other duties, and is forced to handle the service as a mere side issue. The Negro comrades and such white comrades as are familiar with Negro work must be drawn into this work. At present, the service not only sends out news on Party and auxiliary activities, but handles general news as well. This is necessary, but such general news should carry our point of view. Under the present conditions this is not always possible. There should also be more feature articles. In this respect, the Negro students in Russia have greatly helped, but very little aid has been given one way or the other by most of the Negro comrades on the American scene.

It has been pointed out in this article that the very papers to which we have least access are the ones covering the industrial centers and influencing the thoughts and reactions of the Negro proletariat. This means that the Party must make every effort to revive the Negro Champion and to establish that paper as a regular weekly whereby to combat the reactionary influences of the Negro bourgeois press. At the same time we must seek to extend the influence of the Daily Worker among the Negro masses by making that paper a real leader in the fight of the Negro masses against the influence of the ideology of imperialism which expresses itself, in white chauvinism, in terroristic acts against the Negro workers and farmers, in discrimination, in jim-crowism, in racial hostility and separation, etc. The Daily Worker and the rest of the Party press must carry on a persistent campaign against white chauvinism. Only by convincing the Negro masses that we are in earnest will we win their confidence. But we must not only be active in the Negro struggle against white ruling class terrorism, which is part of the world-wide struggle of the proletariat; we must have means of broadcasting to the Negro masses the news of our activities.

There were a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘The Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March, 1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v08n08-aug-1929-communist.pdf