Much of this chapter is devoted to Haywood’s observations, interactions, and empathy with the high desert West’s indigenous people of the 1880s. That Bill Haywood, born in 1869 to a hardscrabble existence of white settlers in s still contested West, grew up to become a tough and imposing man is not surprising. That this giant of a hard rock miner became a deeply empathetic and kind, indomitable warrior for all of the oppressed, is. One of the great figures of the U.S. and international workers’ movement, Haywood’s life story complicates many of the myths and realities of American history. In this, the second chapter of his autobiography, Haywood picks up the story at age 15 as he goes to live with his stepfather in Nevada and describes his first mining job. There he begins his real political education and Haywood spends time on the 1865 massacre of Paiute by U.S. soldiers at Thacker Pass–still contested land–learning of it from a perpetrator and survivor; he speaks of his introduction to the Knights of Labor and the impact of the Haymarket affair; and relates how he got married, lost his first child, and details his work as a cowboy on a Nevada ranch. As entertaining and illuminating a read as you will have all week. First chapter here.

‘Miners, Cowboys, and Indians’ by William D. Haywood from The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood. International Publishers, New York, 1929.

This was my first long journey. We passed through Ogden, going around Great Salt Lake, as the Luzon cut-off had not then been built. I was on the lookout for Corinne and Promontory, as I knew that these places had at one time been the stamping ground of my father and uncle. Promontory was the station where the golden spike was driven when the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific Railroads met from the east and the west. The iron horse, as the Indians called the railroad, had overtaken the covered wagons and ox teams.

For many miles after we left the lake, the lowland was covered with a crust of salt. Then we came to the sage-brush flats of Nevada, which seemed endless. As far as the eye could reach there was nothing but the long stretches of the gray-green shrub. The stations were few and the towns were small. We passed Elko, Battle Mountain and then the Humboldt River came into view on the right. On the morning of the second day I arrived at Winnemucca, went to the hotel, and immediately after dinner took the four-horse stage for Rebel Creek. The stage line extended in those days to Fort McDermitt, an army post. The stage was loaded with freight; I was the only passenger. Inside was a big buffalo coat and a buffalo robe; I thought there would be no chance to get cold. From Winnemucca past the Toll-house was a road through sand hills, which was built of sage-brush laid the width of the wagon track. When tramped down it was for a short time serviceable, but the sands were ever shifting, so that new roads were continually in the process of being built.

We arrived at Kane Springs for supper. It was already dark and getting very cold. When we went to the station, the driver got a drink of whisky. I felt warmer after a cup of hot coffee. After the horses had been changed for a new team, the driver said: “We are ready; let’s go!” I piled into the coach. The buffalo robe and the coat were gone; they belonged to the driver. It was a cold, clear night. In front of us and a little to the right we could see the majestic outline of Granite Peak, in the shelter of which the winter snows were stored, furnishing some water to the flats below. This was my first view of the Santa Rosa range.

When we reached Rebel Creek it was late at night. I had been thinking about unrolling my blankets for a bed. I climbed down from the stage, cold and shivering, and found that supper had been prepared and a clean white bed was awaiting me.

A spring wagon was provided, into which I threw my roll of blankets and my valise, and we drove to Eagle Canyon, two miles up which the Ohio mine was located. There was not a tree in sight; nothing but the scrubby willows that grew along the little stream that flowed down the canyon. There was but one house. It was built of lumber and was about twenty-eight feet long, fourteen feet wide, divided in two by a partition. In the front room bunks were ranged ; double length and three high. In this room there were no chairs, no tables, no furniture of any kind other than a desk and the stuff belonging to the men, consisting almost entirely of blankets and clothing, and a few suitcases and bags thrown under the lower bunks.

The second room had a big cook-stove in the corner, a kitchen table and a cupboard along one wall. Along the other wall, where there was a window, was a long table covered with brown flowerpatterned oil-cloth, with benches running the full length on either side. Overhead on the beams were piled the groceries and other supplies and the bunk of the Chinese cook, which was reached by a ladder. Charley Sing was a good cook, and kept his part of the house scrupulously clean. The other room was also clean, as far as being free from vermin was concerned, but the lumber was without paint and had never seen a plane. There was a little porch in front, a bench over which hung a looking-glass, washpans, a water-bucket alongside the bench, and towels hung against the side of the house. The well was near the creek, in the bottom of the gully. Below the house stood an old stone cabin, half dug-out, with logs, brush, and dirt for a roof. One corner of this was fixed up for use as an assay office. The rest was used for storing cases of canned foods, vegetables, and other supplies.

My stepfather came down from the mine a few minutes ahead of the other men who were working there. He was glad to see me. After meeting the men and having dinner, I unrolled my blankets and spread them on some hay in the bunk over the desk. I put on my overalls and jumper and digging boots that same afternoon and went to work in the mine. My first job was wheeling rock from a shaft that was being sunk at the end of an open cut. I soon found that a wheelbarrow loaded with rock was more than I could handle, so I made the loads lighter and took more trips. I was glad enough when quitting time came.

When we got down to the house it was already dark. The usual mining camp meal was ready, and every one pitched in with a hearty appetite. It was but a few minutes afterward, when the dishes were cleared away, that the men gathered around the table again, reading, playing cards or chess as best they could by flickering candle-light. Others were stretched out in their bunks, or sitting on the edges of them, and so the winter evenings were passed. There was no place to go. The closest town was Winnemucca, sixty miles away. There was one saloon at Willow Creek, the post office, four miles away, but this was seldom patronized, though occasionally some of the men who went to the station brought back a couple of bottles of whisky.

Though miners situated as we were could not keep in close touch with current events, we were all great readers. I remember the second Christmas I was there, one of my relatives sent me a book on baseball. This would have been interesting enough some years before but I was now in a place where one side of a baseball team could not be scratched up in a long day’s ride.

I did not have many books of my own, but the miners all had some. One had a volume of Darwin; others had Voltaire, Shakespeare, Byron, Burns and Milton. These poets were great favorites of my stepfather. We all exchanged books, and quite a valuable library could have been collected among these few men. Some received magazines, and there were four or five daily papers that came to the camp. That they were a week old made little difference to us.

I had a friend about whom I have not yet spoken. This was Tim. He was much more than the ordinary dog one usually meets. A shepherd type, as large as a good-sized collie, his coat was black with brown points and a white patch at his throat. He was quick and strong and had limpid brown eyes, He did not speak my language, but I could understand his tail-wagging, his joyful bark, fierce growl, pathetic whine, and low, peculiar croon. There was something about Tim that always made me think of him as a real person. It was as though the personality of some lovable human had found a place in his being. Instinct was not the only attribute that actuated Tim, although perhaps for scientific reasons I should not venture to assert that Tim could think. Anyway, you know him now well enough to understand the kind of companion such a dog could be to a boy at a mine sixty miles from a railroad, with the nearest neighbor four miles away. The one boy in that section of the country I saw only occasionally, but Tim was with me all the time. He and I had heaps of fun. I helped him out in many a desperate fight we had with lynx, wild-cat and badger.

John Kane was the assayer and ore-sorter at the mine. He took a great liking to me and taught me assaying. He was a big, heavyset, good-natured Irishman with a heavy black mustache and pleasant eyes. When I went to work with him I helped him prepare the samples that were to be assayed. No work I ever did in my life was as fascinating as assaying. These first small ventures into the realm of chemistry led me to feel that I would like to become a mining engineer. I made up my mind to learn this profession and wrote to the Houghton School of Mines and the Columbia School of Mines to learn their requirements for entrance. I secured some books on assaying and surveying and devoted much time to study. But I never entered either of these colleges. I found myself with other responsibilities and my further education was secured in the school of experience.

I took a shotgun one day and started up the canyon looking for grouse or sage-hen, when I ran across a Basque sheep-herder who suggested, “Maybe you want deer?” I told him that would be fine. We went together to his camp on the ridge that divided Eagle Creek from Rebel Creek, where he got his rifle and we started around the summit toward a clump of scraggly poplar trees. There was a thick undergrowth of manzanita. Pointing to a big flat rock on one side of the wood, he handed me his rifle and said, “You go there. I stay here few minutes. Then I go through, maybe deer come out.” I walked over and climbed up to the flat rock, from which I had a clear view of all that side of the woods. Presently I heard the crash of undergrowth, and out burst a beautiful big stag with splendid antlers. I stared at him amazed, when he turned and bounded down toward the bed of the creek, heading into the brush again. In a short time the Basque came plodding through the manzanita over to where I was sitting and asked me: “Did you see deer?” I told him that I had and started to explain what a big buck it was. He interrupted me by asking, “Why you no shoot?” Only then the thought struck me what a splendid shot I could have had at that buck! I tried to tell the Basque that I had forgotten to shoot, but he took his rifle and marched off without a word. I must have had an attack of the “buck-ague.” If I had scared up the deer and left the Basque to do the shooting we would have had venison for supper.

One morning as I came out of the dry gulch on my way to the station I saw a bunch of saddle horses and a crowd of men in front of Andy Kinniger’s place at the mouth of Willow Creek. I hurried on, and heard that Kinniger had been shot and the surgeon from Fort McDermitt was then trying to find the bullet. It was somewhere in the dead man’s skull. I marveled at the skill with which the surgeon had removed the top of the skull to probe down the spinal column where the bullet had lodged. Kinniger had been shot some time the previous evening while he was seated in a chair leaning back against a clump of willows. Later it was proved that Kinniger was killed by One Arm Jim, a Piute Indian, who was arrested, tried, and sentenced to hang. No one could find any motive for the Indian’s action, and every one believed that he was an accessory. A petition was circulated and the sentence of One Arm Jim was commuted to life imprisonment in the Carson Penitentiary. I saw him there many years afterward, when I visited the pen to see Preston and Smith, who were serving life sentences. These were two miners from Goldfield whose story I will tell later. I recall an interesting feature about the penitentiary yard, which had been made by excavating into the mountain side. A rough half circle was dug out, leaving sheer walls, in places sixty to eighty feet high. On the floor of the yard were the imprints of what must have been an elephant or mastodon of prehistoric times, also the footprints of a man which were half again as large as an ordinary man’s footprints. These impressions were made in mud apparently, but had hardened to solid rock. Involuntarily one followed the footprints as they led to the wall. There one-half of the animal’s track was left exposed, the other half was covered by eighty feet of solid rock and alluvial soil. One realized that it was just a little too late; the animal had passed by, perhaps two hundred thousand years before. The wall of time had arisen to prevent our following.

People were sociable in the frontier country. A dance was quite an event. It would be planned some weeks ahead, and people would gather from thirty to forty miles around. It was not unusual for some of the ranchers with their families to drive forty miles to a dance, dance all night and all next day, then drive home. As for dancing partners, there were girls and old women from the ranches, and sometimes Indian squaws would take part. At an impromptu dance at Kinniger’s place Mrs. Snapp from the station at Rebel Creek played the dance music on a three-stringed fiddle, accompanied by Tom Melody, who had contrived a tambourine by putting beans in an empty cigar box.

But more interesting were the Indian dances, where, in a circle cleared on the sage-brush flat, the Indians would gather for their pow-wow and dance sometimes the snake-dance, the ghost-dance, the sun-dance, or some other just as mysterious. Their only music was the drums and the lilt of the squaws. The tunes were plaintive and fantastic, and sounded much alike to me. In the night when the fires were lighted, the hypnotic rhythm of the drums and the springy furtive dance steps of the Indians, accompanied by the low crooning song, were thrillingly weird.

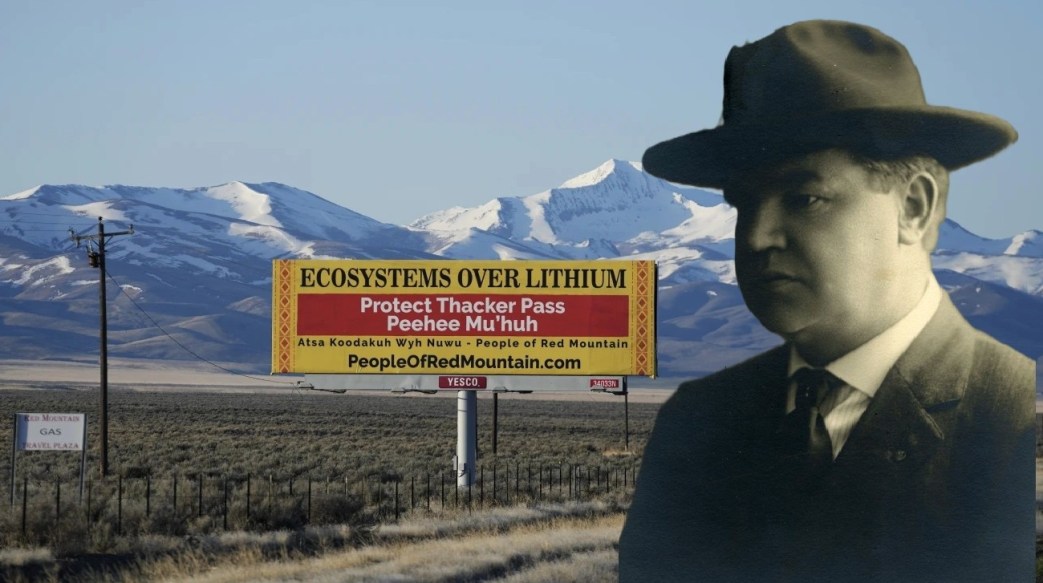

The story of the massacre of the Piute Indians at Thacker Pass was told to me first by Jim Sackett, one of the volunteers who took part in the killing. I also heard the story from Ox Sam, a Piute who had made his escape, one of the only three survivors.

I first heard this hair-raising narrative when old Sackett happened co be a chance visitor at the Ohio mine. It began with an explanation of the many depredations on the part of the Indians throughout southern Oregon and northern Nevada, which caused the white men to organize a volunteer company which, he said, was for mutual protection. This company had been famous as the crack Indian fighters of that section. Their quarters were at Fort McDermitt; from this base they scoured the country looking for Indians. McDermitt was on the western slope of the Santa Rosa range, in the mouth of a branch of the Quin River.

Sackett was an old pensioner who roamed about the country doing little, as he was then too old to work much. There were only a few of his type left. He was at home in the mountains at the cabins of the prospectors or at the ranches along the river in the valley. He wore his hair and his beard long, both grizzled gray. His eyes were weak and looked as though they were sore from alkali dust. As he talked he would squirt tobacco juice at an object he had located as a target, and hit it with remarkable precision. His story started:

“That day we had camped at the mouth of Willow Creek, just above where Andy Kinniger’s house stands now. We were settling down for a good night’s sleep when the call came for boots and saddles. Now what’s up? The outfit was ready to move in a very short time, mules packed and horses saddled. The captain coming up pointed across the valley in the direction of what is now called Thacker Pass, saying, ‘If you look close you can see a fire there. Before dusk I thought I could see smoke but now I see the fire. It is an Indian camp. We’ve got to get there by daylight. We’ll start when it gets a little darker.’ It was a long ride across the sagebrush flat and through the meadows as we got close to the river, which we had to swim. More meadows and then the sage-brush again. One of the horses stepped into a badger hole and broke his leg. We couldn’t kill him until next day. They might have heard the shot and we did not want to alarm them. Here the company divided; part were sent ahead to ride down the pass to the camp, a small detachment was left with the pack animals and extra saddle horses, the rest of us rode up the pass.

“Daylight was just breaking when we came in sight of the Indian camp. All were asleep. We unslung our carbines, loosened our sixshooters, and started into that camp of savages at a gallop, shooting through their wickiups as we came. Ina second, sleepy-eyed squaws and bucks and little children were darting about, dazed with the sudden onslaught, but they were shot down before they came to their waking senses. The other detachment came rushing in but did no shooting until they were close up. From one wickiup to another we went, pouring in our bullets. Then we dismounted to make a closer examination. In one wickiup we found two little papooses still alive. One soldier said, ‘Make a clean-up. Nits make lice.’ When Charley Thacker spoke up, saying, ‘I’d like to keep those two if there ain’t no serious objection.’ Before it was decided, some one sang out, ‘There’s one gettin’ away!’ He was already a mile off on a big gray horse going like the wind. Some of us began to shoot, several got on their horses and started after him. But it was too late, he escaped. They soon returned. Those of the Indians who were only wounded we put out of their misery, and then mounted and rode away, Charley Thacker carrying his two papooses behind him.”

These young ones grew to manhood and were known as Jimmy and Charley Thacker. When I knew them they had gone back to the nomadic life of the Indians. Both were fine, stalwart men; as men, I imagine, much better than those who had helped kill their fathers and mothers, relatives and friends.

Old Sackett’s tale seemed to pull a lot of the fringe off the buckskin clothes of the alluring Indian fighters I had read about in dime novels. There was nothing I had ever read about, with heart palpitating, of killing women and little children while they were asleep. The old volunteer’s exploits were at a discount with me after that, and declined even more when Ox Sam, some months later, told me in his pidgin English what had happened at Thacker Pass. He made no additions to the story, but it was the feeling in the things he said that Sackett did not possess. The old Indian buck was one day sitting on a sack of charcoal at the door of the half dug-out cabin which we used as an assay office. I went out and sat down beside him, asking him how his squaw Maggie and his papooses were. “Pretty good,” he answered. I said, “Sam, tell me about Thacker Pass.” He glanced up with a distant look in his eyes, murmuring, “Long time ago. No much talk about now.” But I said, “Sam, I would like to know why the white men kill Indians. Do you know?” Sam’s eyes narrowed. “Yes, I sabe. You no sabe?” I told him that I did not. Sam began:

“Long time ago same time I born, maybe before, no white man stay in Nevada. That time Piute live pretty good. In spring, catch em plenty fish, dry em, smoke em. Lots duck, lotsa goose, smoke em, too. In the fall, kill em deer, jerk em meat. First time frost come, catch em plenty pine-nut. All time lotsa rabbit, lotsa sagehen. Piute no sabe big ranch, no make em farm, all same live pretty good. Some time Bannock, some time Shoshone man steal em Piute squaw. We make em fight. Some time Piute steal Shoshone, Bannock squaw; make em pretty good fight. Some time make em big gamble; some time big dance; some time big pow-wow. Hot, cold, all same. Piute live. When him die, make up big pile rock, him stay inside. Got bow and arrow, good knife, kill em good pony, Piute go happy hunting ground. Everything good.

“White man, he come. He make em little farm, some time marry Piute squaw. That’s pretty good. Mix em blood all same like Bannock, Shoshone. Pretty soon come more white man. Him prospector; him pretty good. I no sabe, all time dig hole, make em big pile rock, dig em more hole. He no stay long one place. Soldier man come. No sabe soldier. He no got em farm, he no dig em hole, he no do nothing; say all time ‘Uncle Sam.’ He all live one house, no woman. Ino sabe. All time talk em ‘squaw, squaw.’ He got fire-water, give em Piute, make em crazy all same white man. All Indians have big pow-wow. Big Chief say, what matter now? Too much trouble all time. Indian like em fire-water, fire-water he no good. Soldier give Indian fire-water. No like fire-water. Indian sell em mink-skin, badger-skin, all kind of skin to soldier. Sell em squaw, too, for fire-water. By and by Indian he crazy. No more fire-water, all same crazy. Chief say soldier not much good. Indian say all white men not much good. Pretty soon white man kill em Piute. Indian no much sabe, he kill em white man. That’s pretty bade time. Soldier hunt Piute all same coyote. That’s time Thacker Pass. Lots of Indians going Quin River sink to get ducks, goose. That morning soldier come quick, shoot, shoot. I cut wickiup skin behind, go quick and get on big white horse, ride fast; soldier no catch em, no shoot em. I ride Disaster Peak. Long time hide. My father, my mother, my sisters, my brothers, I no see no more. Long time ago. Not much talk about now.”

Old Sam ended with a tremor in his voice and moisture in his eyes. “Yes, I sabe, I sabe.” Grasping his hand, I said, “You stay a little while; Sam. We’ll have dinner pretty soon.”

There was a wide historical meaning in the brief story that Ox Sam, the Piute Indian, told me. It began when the earliest settlers stole Manhattan Island. It continued across the continent. The ruling class with glass beads, bad whisky, Bibles and rifles continued the massacre from Astor Place to Astoria.

Half-way between the camp and the mouth of the canyon there was a big ledge of quartz, the outcropping of which stood high, cleaving the mountain from base to summit. Charley Day, who was then working in the Ohio mine, had located this cropping, but said that he never intended to do the assessment work on it. One night he said, “I’ll give you the Caledonia mine if you want it.” With the thought of being a mine owner, I accepted from him the quitclaim deed, to make which binding I gave him the legally required sum of one dollar. I used to pass this claim with the idea of working it some time, but having come into possession of it so cheaply, I ignored its possible value. Some years later I worked in it as a miner, after Doctor Hanson of Winnemucca had relocated it, organized a company and erected a quartz mill. I had neglected the assessment work and my right had long before expired. It came into the possession of the Caledonia Mining and Milling Company. When the first lot of ore was run through the mill every one was excited as to what the returns were going to be. We had heard different reports as to how the assays were running and that some nuggets had been caught in the battery or ore-crusher. But we never knew the returns, as a nephew of the doctor ran away with the entire output, and as far as I knew was never caught. After this episode there was an air of discouragement and pessimism about the mine. The men did not know whether they were going to get their pay or not, and shortly afterward I quit.

Coming down the trail from the mine one day, John Kane and I were skylarking and I jumped on his back. He fell and broke his leg. The other men helped carry him down to the bunk-house; I started off to Rebel Creek to get a team and spring wagon to take John to the hospital at Fort McDermitt. We put a mattress in the wagon, got John in and started on the thirty-mile drive to the surgeon. It must have been a painful trip for him, but the surgeon did a good job and six weeks later John was back at work. That is, he was working in the assay office hobbling about on a crutch.

Men situated as we were sometimes form close friendships. This was true of Pat Reynolds and myself. Pat was the oldest man on the job, tall, raw-boned, with a red chin-whisker, bushy eyebrows and a strawberry mark on the outer corner of his left eye. It was this old Irishman who gave me my first lessons in unionism. Pat was a member of the Knights of Labor, and some of the things he told me about this organization I could not well understand at the time. I had never heard of the need of workingmen organizing for mutual protection. In that part of the country there did not seem to be a wide division between the boss and the men. The old man who was the boss slept in the same room and ate at the same table and appeared the same as the rest of the men. But Pat explained that he was not the real boss; that none of us knew the owner of the mine. Mentioning the large ranches in the vicinity, he said, “The owners live in California, while the men who do all the work and make the ranches and mines of value are here in Nevada.” He told me about the unions he had belonged to, the miners’ union in Bodie, California, and the Virginia City Miners’ Union in Nevada, organized in 1867, the first miners’ union in America. These two unions were among the first that formed the Western Federation of Miners. It was some time before I got the full significance of a remark that he made, that if the working class was to be emancipated, the workers themselves must accomplish it. Early in May, 1886, this thought was driven more deeply into my mind by reading in the newspapers the details of the Haymarket Riot, and later the speeches that were made by the men who were put to trial. The facts and details I talked over every day with Pat Reynolds. I was trying to fathom in my own mind the reason for the explosion. Were the strikers responsible for it? Was it the men who were their spokesmen? Why were the policemen in Haymarket Square? Who threw the bomb? It was not Albert Parsons or any one that he knew; if it had been, why did Albert Parsons walk into court and surrender himself? Who were those who were so anxious to hang these men they called anarchists? Were they of the same capitalist class that Pat Reynolds was always talking to me about? The last words of August Spies kept running through my mind: “There will come a time when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you are strangling to-day.” It was a turning point in my life.

I told Pat that I would like to join the Knights of Labor. From this time, although there was never an opportunity to join, I was a member in the making.

Soon after this I made my first visit home since I had begun to work in the mine. After a few weeks I returned to Nevada. The next year was a year of financial crisis, and panics of this kind affect the miner as well as the workers in other industries. The Ohio mine was closed down, and I was left in charge. I lived alone at the camp with my dogs for company, and did my own cooking.

Some time later I returned to Utah and went to work in the Brooklyn mine. My first job there was firing the boilers and running the top car, taking away the waste and ore that were sent to the surface. The Brooklyn was an inclined shaft fourteen hundred feet deep, in which there was a skip that was hauled up by the engine for which I was firing the boilers. For a while I worked in what was called the Mormon stope; it had been given this name because several of the men employed there were from the San Pete valley, a strictly Mormon section. I worked in several different places in this mine, which was producing lead. There were men going to and coming from the hospital all the time, suffering from lead poisoning. This is one of the serious vocational diseases with which the workers have to contend, but there was no provision made for them. In that part of the country the miners were sent to hospitals in Salt Lake City which they themselves maintained. Every miner had one dollar a month taken out of his wages by the company for hospital services. Their transportation to and from the hospital the workers had to pay themselves. A crowd of lead miners presents a ghastly appearance, as their faces are ashen pale.

There are many dangers to which a miner is exposed besides rheumatism, consumption, lead poisoning, and other diseases. One of these is the constant danger of falling rock when a mine is not kept closely timbered. I was working but a short distance from Louis Fontaine when he was killed by a slab of rock from the roof that crushed his head on the drill that he was holding. We got the body out of the stope on a timber truck, ran it to the station, and put all that was left of Louis in the skip. We rang three bells for the surface. Some of us laid off to go to the funeral.

The men rode on the skip coming up to dinner at quitting time. Four could sit in the skip on either side, two on the crossbar, and one on the angle to which the steel cable was fastened. One day I got on the cable behind the man on the angle and rode all the way to the top. It was one of the most hair-raising experiences of my life. The cable was whipping the timbers at the top and the rollers on which the skip ran up the steep incline. I was afraid every second that my hands would be caught as I held on to the cable behind my head, and I gripped the man in front of me with both legs to keep from turning on the rope.

While at the Brooklyn mine, I sent to Nevada for my sweetheart, Nevada, Jane Minor. We were married and went to live in Salt Lake City, where our first child was born, a boy who died at birth: Shortly afterward we returned to Nevada, where I spent some time doing assessment work for Thad Hoppin, and prospecting, I later went to work on the Hoppin ranch.

A cowboy’s life is not the joyous, adventurous existence shown in the moving pictures, read about in cheap novels, or to be seen in World’s Exhibitions. The cowboy’s work begins at daybreak. If he is on the ranch he rolls out of bed, slips on his pants, boots and hat and goes to the barn to feed his saddle horses. It is his greatest pride that he does not work on foot. Coming back, he washes his face and hands at the pump, and takes his place at the long table; the Chinese cook brings in piles of beefsteaks, potatoes, hot cakes, and “long butter,” as the flour-gravy is called, because on a big cattle ranch where there are thousands of cows, ofttimes there will be not one milk cow, and no butter but what is hauled many miles from town to the ranch.

There are various kinds of work for the cowboy to do during the different seasons on a cow ranch. The cattle are not pastured or herded, but run wild on the mountains and sage-brush flats. They are rounded up in the Spring and Fall, the round-up being called the “rodeo.” This and other words commonly used in the southwest come down to us from the days when this part of the country was a Spanish colony, and Spanish was the usual language. The foreman, who was called major-domo, of the biggest ranch in the neighborhood issued the call for the rodeo. Cowboys from all the ranches in a radius of a hundred miles or more came with their saddle horses, each bringing three or four. The bedding consisted of a couple of blankets and a bed-canvas. When traveling with the rodeo, the men rolled up their bedding and put it in the chuck wagon which also carried the cooking utensils and the grub. Starting from the home ranch the outfit would camp on the banks of a stream or near a spring or sometimes would be compelled to make a dry camp, in which case they hauled along barrels of water for the emergency. After supper we stretched our beds on the ground, gambled and otherwise amused ourselves, telling stories of past experience and singing lilting and rollicking songs. A horse-wrangler or two guarded the paratha, the herd of saddle horses. We all went to sleep as soon as night fell. At the first break of day, the cook was up getting breakfast. The wranglers brought the horses. The cowboys went to the corral. Each roped his horse out of the band, saddled and bridled it and then went to the chuck wagon for breakfast.

After eating we rolled cigarettes, mounted our horses and started for the mountains, some going up one canyon, some up another. We rode to the highest summits. Turning, we drove before us all the cattle on that part of the range. The round-up took place in the valley below, where the cattle were brought together. The cowboys formed a circle around them, fifty or a hundred cowboys spaced out around several hundred head of cattle. Two or four cowboys from the biggest ranch rode among the herd and drove out the cows and young calves; they were able to recognize their own by the brands and earmarks on the cows. The task was then for the cowboys from each ranch to brand and earmark the calves that belonged to the ranch they were working for. The parting out continued until all the cows and young calves were separated from the herd. The other cattle were started back to the mountains. Two or three small fires were lit in the corral and the first bunch of cows was driven in; the other bunches were held to await their turn. We roped the calves by the hind legs and dragged them near the fire by taking a turn with the rope around the horns of our saddles. We cut the ears of the calves with our own peculiar marks, crop, underbit, swallow-fork or other designs. The brand of the ranch was burnt into hip or shoulder. This proceeded until all the calves were branded and earmarked, the males gelded, leaving one out of every twenty-five or fifty for breeding purposes, selecting those which in the opinion of the cowboys would make big, strong animals. Outside of the bawling and bellowing of the calves and cows, there was silence; we had little to say while at work, as we were nearly choked with dust.

Meanwhile the chuck wagon had moved on to the next camping ground. If the horses had not had a hard day’s work we would start for our supper at a long, swinging lope, singing ribald songs at the top of our voices. Unsaddling the horses where we were going to make our beds for the night, we washed up and were ready with ravenous appetites for grub. The day’s work was done. The roundup took several weeks; we went up one side of the valley and down the other side.

Another round-up took place every fall, when beef steers were gathered for the market. It was carried on in much the same way though we used to take more care not to drive the animals fast because of the weight that would be lost from marketable steers.

When beef was needed for the camp, a young heifer or steer was killed. The cowboys as a rule used to barbecue the head and other parts of the animal. This was done by heating rocks which were put into a hole that had been prepared, the head and pieces of meat being wrapped in pieces of wet canvas, put on top of the hot rocks and covered with dirt. In the morning we would dig it out, remove the canvas and the hide, and with a little pepper and salt the main part of our breakfast was ready.

Wild horses are more fleet-footed than cattle and more difficult to handle. After the round-up of horses, those that were wanted for harness and saddle were kept in field or corral until the slack season of fall and winter, when they were broken to work or ride. This was the most exhilarating part of a cowboy’s life. There was much excitement in riding wild horses as well as in handling them, not only for the rider but for the onlookers. Some horses were extremely vicious, biting, striking and kicking fiercely, to say nothing of their bucking propensities.

“I’m going to ride that roan colt to-day,” said Tom Minor, my brother-in-law, as we were rolling out of bed in the bunk-house of Hoppin’s ranch.

“I bet he’ll pitch some,” remarked John White.

“Oh, I don’t know,” said Tom, “I think he’ll be as easy as a rockin’ chair.”

After breakfast six or eight cowboys went out to the corral. It was a bright, sparkling morning, the air was clean with a light frost. John White had a lasso on his arm and moved toward the horses, saying, “They’re full of ginger this morning, Tom,” as he threw his rope around the neck of a rangy roan colt, and sat back on the rope. Two of the boys ran up to help him, and Minor started toward the horse, his hands slipping along the taut lasso.

“Whoa, Rockin’-chair,” he purred, reaching out his-hand to the colt, which was used neither to its new name nor to the smell of human beings. The horse reared and struck out with both fore feet. After repeated efforts and much stroking, a halter was finally slipped over its head, and a leather blindfold was pulled down over its eyes. The lasso was taken off and the colt stood quivering in every nerve. Tom kept murmuring, “Whoa, Rockin’-chair.” With sidewise and forward motions, they got the horse near the fence and tied him to a post. Tom tossed a blanket on him, but he kicked, snorted and bucked until he got it off. This was repeated until the colt came to the conclusion that he was not being hurt. He was led out to the open field, where, with much careful persuasion, he was hackamored and saddled. Minor, fastening on his big roweled spurs, with a quirt on his right wrist and reins in the left hand, which was on the horn of the saddle, placed his left foot in the stirrup and was on. He reached over and pulled up the blindfold, hit the colt on the shoulder with his quirt, and Rockin’-chair began to buck, all four feet bunched, his head down between his forelegs. His back bulged up like a camel’s hump, while Minor was gouging him with his spurs and whipping him with his quirt. White sang out, “Lovely Jesus! but can’t he buck? Some Rockin’-chair!”

The horse twisted, corkscrewed, cavorted and did everything a horse could do except roll. When he was completely exhausted Tom rode him back to the corral and got down. Then one of the boys took Rockin’-chair and unsaddled him. Minor said to the group who had come to shake hands with him, “He’s a tough gazabo. We’ll save him for the Pendleton round-up.”

The cowboys and miners of the West led dreary and lonesome lives. They had drifted westward from points of civilization, losing contact with social life. Young and vigorous, they were bursting with enthusiasm which occasionally broke out in wild drinking sprees and shooting scrapes. They were deprived of the friendship of women, as the country was not yet settled, and when they visited the small towns on the railroad they gave vent to their exuberant feelings.

We saw dust coming up the valley road one day and wondered who it might be. Looking again a little later, we could see a sorrel team and a light buggy, but we did not recognize the occupant even when he pulled into the yard. We went out and asked him to unhitch and have supper. He told us that his name was Henry Miller. We had never seen him before, but knew him as one of the biggest ranch owners of the West. Putting his team in the barn after watering the horses and giving them a feed of hay, we took Miller to the house and seated him in the kitchen while we set about preparing supper. One of us—there were only two men on the ranch at that time—reached up and took down a package of coffee from the shelf, when Miller broke in: “Now I see why Hoppin goes broke. He feeds de ranch-hands Arpuckle’s coffee! No vunder he goes broke; I vould go broke, too, if I gif my men Arpuckle’s coffee!” We did not comment on this outburst, as the coffee seemed cheap enough to us. In the course of the evening Henry Miller told us how he had made his tremendous fortune. He said: “I starts out mit a basket of meat on my arm; I peddles it from house to house. I make me not vun fortune, but tree fortunes; I make vun fortune for Lux, vun for de goddam lawyers and tieves, and vun for mineself. If it vas not for de goddam lawyers and tieves, I own now de whole dam state of California. Anyhow, I got it some land; I can travel from mine wheat ranch in Modesto to de Whitehorse ranch in Oregon mit a team and stop on mine own land every night.” Lux was his business partner; Miller and Lux was a powerful firm of meat-raisers and wheat-growers in California, which exploited the state in the early days.

We were always busy on the Hoppin ranch. According to the season, sheep-shearing, breaking horses, handling the cattle, or haying kept us on the go. There were three hay ranches, one alone of which was three thousand acres.

At this time Fort McDermitt was abandoned by the army. There was no industrial center anywhere near, and the Indians were practically all exterminated. My father-in-law was appointed custodian of the government property. My wife and I went to live alone at the old deserted army post until the family could arrange to move there from Willow Creek.

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/download/autobiographyofw0000hayw/autobiographyofw0000hayw.pdf