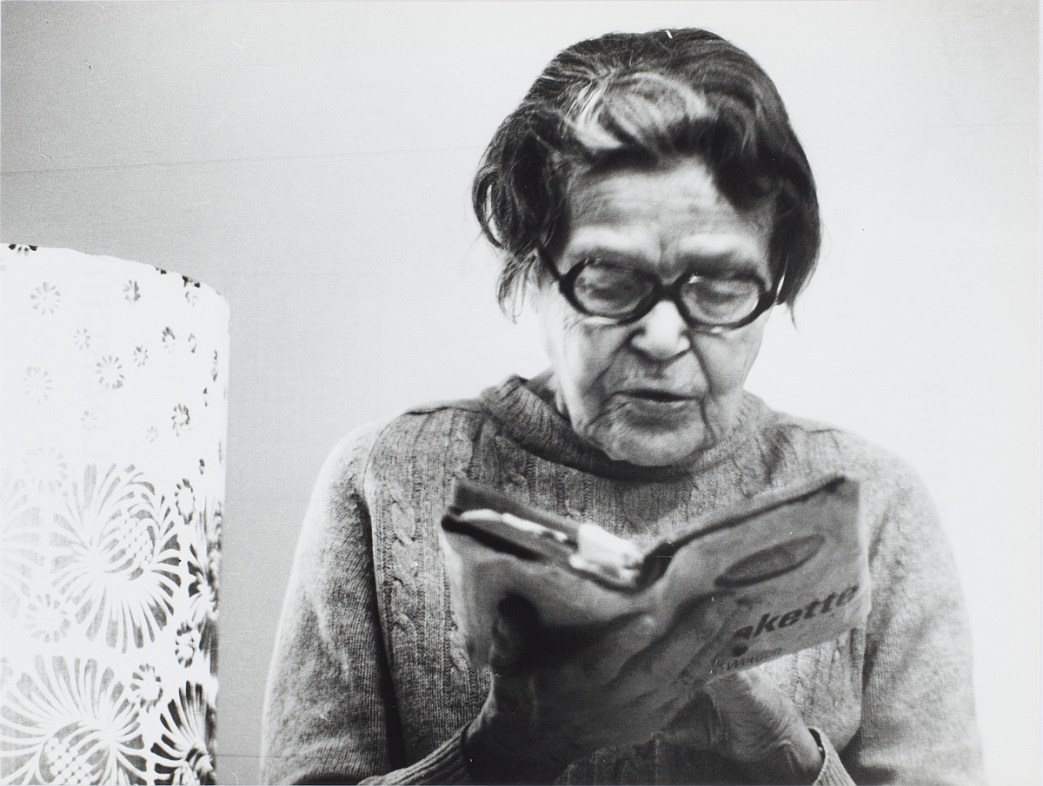

A fascinating, and frighteningly familiar, look at the anti-intellectual language of emotional obfuscation employed by the Nazis from Marxist linguist Trude Richter. With a dramatic and fascinating biography, Richter was a teacher and literary critic who became secretary of the German Association of Proletarian-Revolutionary Authors in 1931. An active Communist, after a year of underground work escaped to the Soviet Union in 1934 where she finished her post-doctoral work and taught linguistics. Arrested with her husband during the Purges in November, 1936 she would spend almost two decades in Siberian labor camps, where her husband died of typhus in 1938. Remaining a committed anti-fascist and Communist, after her final release in 1953 and ‘rehabilitation’ in 1956, she returned to the German Democratic Republic as a member of the ruling Socialist Unity Party. Living in Leipzig she became a leading figure in the Johannes R. Becher-Institut (today’s German Institute for Literature) and wrote extensively, including her memoirs which were published posthumously after her 1989 death. The article below makes for an important read in light of today’s language of a rising right.

‘Fascism and Language’ by Trude Richter from International Literature. No. 4. April, 1935.

“Language is the proximate reality of thought.” (Marx, Deutsche Ideologie)

Investigating the language trends of fascism is as illuminating as it is important. Illuminating, because the contradictory ideologies of the Nazis find their formal precipitate in language. Important because the German language is one of the cultural values that the victorious proletariat will inherit, or has already inherited. The German language—the language of Goethe, Hegel, and Heine, and above all, the language in which Capital and The Communist Manifesto were written—is a highly developed cultural instrument, whose maintenance, enrichment, or decay is closely related to general cultural and political conditions.

To begin with, profound changes in the basic structure of a language: phonetic as well as etymological “linguistic revolutions,” can occur only as a sequel to social revolutions. The rise of feudalism around the year 1200 and the rise of the bourgeoisie in the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries were accompanied by tremendous linguistic changes, even though the latter do not always reach full maturity, as was the case in Germany. With the consolidation of new ruling class, a thoroughly refurnished language comes to the fore, reflecting the advance in the economic as well as the cultural field. Since fascism leaves capitalist class relationships untouched, and since it represents merely the final stage of declining bourgeois class rule, its linguistic consequences are confined to the promotion or suppression of already existent trends in style.

The language of imperialist Germany is a far from homogenous formation, corresponding to the complicated social structure of the country. Feudal reaction was never completely silenced in Germany; neither the Junker nor his petty bourgeois counterpart, the guild craftsman, vanished from the sociological scene. On the other hand, a powerful imperialist bourgeoisie and a strong proletariat grew into decisive political factors as the nineteenth century drew to a close. An army of millions of officials and office workers, the widely ramified stratum of small investors, arose for the first time an the cities, while peasant landed property, both rich and poor, persisted in various areas.

No less multicolored is the confusion of various ideologies, since numerous half-reactionary or wholly reactionary concepts have survived alongside progressive bourgeois thought and the revolutionary proletarian Weltanschauung. Style and language trends also differ, according to the differences in ideals and educational traditions of the several classes and sections of the population. It was from this abundant reservoir that the national socialists drew their language “program.” Depending upon the immediate end in view, one tendency or another is diverted into the channel of the fascist movement. However boundless its eclecticism, its goal has always been unchanging: barbaric reaction.

“National Rejuvenation”

This is the official slogan of fascist language policy. As in most other fields, national socialism is here, too, merely continuing what reactionary bourgeois circles began long ago. Adolf Bartels, the senile literary pope of the Nazis, embodies in his aged person the adoption of the old Nationalist language aims. He and his ilk have been combatting every borrowed word; what is more, they want to purify the German language of “destructive intellectualism” in which they always sniff the Marxist, and usually, the Jewish element. They preach the style of the “clod,” i.e. the return to a primitive peasant language. They are as little interested in the living, realist peasant language as in the actual interests of the peasants. For behind these purist demands there are concealed the reactionary anti-capitalist desires of the German Junkers, who long for the vanished blessings of feudalism.

It is characteristic of the intellectual and political degeneracy of the German petty bourgeoisie that it has always been ready to make propaganda for feudal ideologies. The fight against the enlightened intelligentsia of the big cities—left bourgeois as well as proletarian—was romantically clothed as a fight against “intellectualism and asphalt literature,” while the backward, miserable existence of the impoverished small peasants and farm laborers was hypocritically glorified in bombastic, primitive language. These tendencies, more than a century old, have come to life again in the national socialist “blood mysticism” and “contact with the soil.” Today they are to serve as propaganda among the thousands of unemployed, who are compelled to work for the big agrarians for a plate of soup; in addition, they are to act as stupefying drugs for all the discontented and enlightened among the propertyless classes.

When the big bourgeoisie also demands this pure German language today through its political organs, the fascists, it champions its own interests, of course. It is interested in replacing internationalism within the proletariat by reactionary, chauvinist nationalism, which makes patient cannon-fodder out of revolutionary class fighters. It wants to prepare the workers’ brains in such a way that they are no longer equal to Marxist concepts, so that Marxism becomes simply “inconceivable.” The weapon employed for this purpose is the systematic use of a definitely non-conceptual, primitive language. This is quite frankly proclaimed by the leader of the fascist writers, Hans Freidrich Blunck, President of the Reich Chamber of Literature. He writes as follows in his programmatic article “The Right of the German Language” (Voelkischer Beobachter, Sept. 24, 1934):

“During the past few decades an effort has been made to establish equal rights in language usage by stuffing the so-called uneducated with borrowed words and foreign concepts [this is the stumbling-block!—T.R.], the belief that this meant elevating them. The endeavor failed. In the future we shall have to follow the other path, and find our way back to pure German word formations intelligible to everyone, which are to aid, and can decisively aid in preventing the renewed production of a proletariat in later generations.”

What he means is the mew formation of a class-conscious proletariat. The class of the exploited “in itself” remains; but it should not be raised to the status of a class “for itself.” Blunck also reveals the roads that are to lead to this goal:

“In order to form mew words, easily understandable and intelligible, we shall delve more boldly than before into the boundless wealth of German root-words. We shall preserve fortunate new word formations in a new German Language Office, and insist that they be used…We shall not confine ourselves to clearing out the scientists’ gibberish, but shall go after everyday matters as well.” The conclusion of the article glorifies this obviously reactionary-dictatorial language policy in the following characteristic sentence: “Language and word, whose roots have flowed to us from four or five Ewen, must be kept pure and holy by us!”

This sentence is typical of the “nationally renewed” language, both in the impossible metaphor of the roots that “flow” and in the arbitrarily employed word Ewen, obsolete for the past 400 years, as well as in the illogical juxtaposition of “language and word.” (Logically, it should read: sentence structure and word.) It is this very inability to write a precise German that has gained for Blunck, formerly a quite unnoticed poetaster, his present high post. In one respect that bold-face concluding slogan of his is really a language masterpiece: it has made the social, class background of its theme vanish completely, impressing the naive reader by a robust phrase.

Griese, Billinger, and all the other “countryside poets” write this kind of deliberately primitive German. The content of their writing is directly and consciously aimed against everything progressive, against Marxism, above all, of course. Since it is impossible to get anywhere in this respect by subtle logical argumentation—it might even stimulate the reader to do some thinking of his own—these writers resort to a purposely clumsy, meagre language, try to paste up the cracks in their logical structure with this formless mass.

Let us take as an example Rosse (Horses), a drama by Billinger, one of the plays produced most often during the past year. The title itself is an extinct word. It too demonstrates the spuriousness of the “folk” language. In this fascist piece of hack work, the fact of mass unemployment is expressed thus: “My three sons’re back home again, the factory hasn’t any use for them; the machine’s already eaten up all the work in town.”

The language is neither pure German nor a dialect, least of all the ee of a rich peasant with a well-stocked stable of horses, whose sons don’t have to go to work in a factory in town at all! The ancient threadbare argument against technology cannot stand any sensible dialogue— let’s not start any debates!—that is why the complicated capitalist economic system is portrayed by the primitive image of a gluttonous cow. On this language level discussion is indeed impossible! Another reason for this speciously simple language is the hypocrisy of anti-technicism. Whereas in the play the “horse” is pictured as a holy thing in contrast to the devilish tractor, the parvenu postaster does not think of giving up his elegant auto. The big agrarians and the bourgeoisie keep on introducing the new machines wherever it increases their profits.

The prescribed purification of the language is being carried out with extreme rigor in the schools, editorial offices, and government institutions. It is primarily aimed against words borrowed from other languages. This fight against the borrowed word has direct economic causes, in addition to the political ones. Every borrowed word that really penetrates into popular usage is tangible evidence of the intensive, fruitful contact of the country with other highly civilized peoples. These expressions thus taken over do not remain linguistic foreign bodies for a long time. They fuse with the language of the people absorbing them to the extent that the things they denote really become part of the daily life of the mass of the population. The greatest example of this role of borrowed words as a manifestation of mass cultural progress is offered by the Soviet Union. If hundreds of English, German and other expressions are enriching the language of the Russian workers and peasants today, it simply means that the victorious proletariat has taken over the latest, highest achievements of technology, science, and a cultural standard of living from other peoples and is using them in socialist construction to raise the cultural level of the whole working population. Fascism, on the other hand, systematically impairs the living standard of the proletarians, peasants, and petty bourgeoisie. For in the epoch of the general crisis the German capitalists, as well as the backward landed proprietors, can sell their goods in the domestic market at profitable prices only if they close their borders to cheaper foreign products. This monopoly policy not only raises the cost of living for the masses; it also lowers their living standard directly. Inferior domestic substitutes are used in place of the good imported raw materials. There is no longer any technical or scientific progress that helps the masses in any way. (At most, advances in fields that are aimed against the masses: the armaments industry, etc.) That is why there is no real incentive in fascist Germany for enriching the language with new, borrowed expressions. This economic state of affairs also plays a part in the demand for radical cultural autarchy, as is in combatting the use of foreign words.

“Steely Romanticism”

National traits are by no means the sole linguistic register played on by national socialism. It plays other tunes too, depending upon the given situation and the class composition of its listeners and readers. Let us examine, for instance, the following poem from the standpoint of its language type:

SWORDS By Peter Hagen

[From the play Lichtnacht der Wende (Light Night of Change)]

Swords sing in the night

Thrown in a clashing heap

Sparkling with flashing splendor

Songs of imperious might.

Here we stand under proud flesh

Healing wounds of the fray

Hurling the swords on high

Steely victory choir.

Slender as flames of fire

Is the sheen of our blades

Sparks over country asleep

Flash like awakening lightning.

Swords sing in the night

Steel is—cruel and sublime—

Always as weapon and shield

Answer to insolent greed.

Which we under the proudflesh

Healing wounds of the fight

Throw in a clashing heap

Swords sing in the night.

Here the primitive language is deliberately avoided. Sentence structure and choice of words are extremely affected, even new words are coined, such as Geglitz (rendered as sheen, stanza 3). The purpose of the form is disclosed only through the content: the swords praised in the poem serve of course in 1934 merely as a symbol of modern military technique, (tanks, gas bombs, etc.). In other words, the poet glorifies the rearmament of present-day Germany. But not by portraying it realistically! On the contrary, an abstraction is made of everything concrete: all spatial, temporal, and specific circumstances are left out. Most important of all, not a syllable mentions the social basis and function of these armaments. What remains is a wholly isolated, wholly general concept, inconceivable in point of time and void of content: the weapon is praised—the “pure phenomenon” of steel is celebrated. But “there are no ‘pure’ phenomena, and there can be none, either in nature or in society” (Lenin, “Collapse of the Second International,” Collected Works, Vol. XVIII, P. 300). Such abstractions, hostile to reality, pale and void of content, cam never furnish the meaningful structure for a poem, for the latter is bound up with the portrayal of some sequence of images or thoughts, the reproduction of concrete definitions and connections. That is why stanzas or limes can be shifted about at will in the poem we have taken as an ex-ample without the change being noticeable—the poem’s chief artistic feature is its extreme poverty of content.

For this nothingness to appear as a grandiloquent something, aye, as “eternal truth,” it must be clothed in a language that is also as far removed as possible from the tangibility of objective reality both in imagery and choice of words. Its tinny pathos and its affected language thus arise as the formal counterpart of its antirealist content.

We should not have discussed this pitiable hack work in such detail if it were not characteristic of the fascist endeavors to revive expressionism in style. All the poem’s features of form and content resemble the expressionist. Around 1920 the perplexed petty-bourgeois intelligentsia tried to find a way out of the chaos of war, revolution, and inflation (impenetrable for them) by tearing the phenomena of social life out of their casual concrete relationship, and proclaiming the meaningless . abstraction thus obtained as the “pure essence” of things. Doing this, they were necessarily compelled to use unrelated hysterical outcries, exaggerations, choppy sentences and cramped pathos.

The creative method of expressionism and its language tendencies offer much that is attractive to the fascist esthetes. “Expressionism had healthy roots,” was Goebbels’ praise; he set it up as a model of a genuine trend in style. The very thing that characterizes expressionism as a symptom of the imperialist bourgeoisie’s decay—its irrationalism, its rejection of causality, its pronounced anti-realism—all that is praised by the Nazis as great art, since it serves as a pattern for their own aims in art: the absolute avoidance of any portrayal of social reality.

Only in this way can fascist themes be worked into “sublime works of art.” The heroic “attitude” that the Nazis demand of their followers, the “roaring enthusiasm” for death as cannon-fodder, would reveal its true character at once if it were pictured in a concrete, realistic language, ie. in its social context. Obfuscation and warlike ecstasy are produced rather by a cramped, pathetic speech, or as Goebbels phrases. it: by “steely romanticism.” Moreover, the continuation of certain expressionist language trends is the only cultural bait that the Nazis can offer the educated bourgeoisie. Such “sublime works of art” are the highest formal achievements of which fascist literature is capable.

“The Standard-Bearers of the German Revolution!”

Hitler would never have gotten his mass following among the peasant and the petty bourgeoisie, which helped him to power, if he had not stupefied the masses with his unscrupulous agitation. This was done deliberately and methodically. With all their contempt of the “spiritless mass,” the fascists knew how to pose as the friends of the exploited and oppressed. With cynical frankness, Goebbels subsequently disclosed the tricks that helped him and his ilk into the saddle. His propaganda did not try to convince the masses, but to “sweep over them like a fluid, to which everyone finally falls victim whether he wants to or not” (Angriff, May 9, 1933). The truth—for Marxism the chief argument —plays no part at all here. Lies, slander, betrayal, swindle—all of them are sanctified by success:

“It is just as naive to reject a certain kind of propaganda because of its methods. Propaganda is not an end in itself; it is merely a means to an end. If it attains its goal, it is good. If it doesn’t attain its goal, it is bad. How it attains its goal is immaterial…for propaganda is a matter of the possibility of success” (Goebbels in the Angriff, May 9, 1933).

What is the language of these clever deceivers of the people, when they court the favor of millions? The answer is easy enough: plain speech for the plain man! The “plain man of the people,” this principal addressee of fascist demagogy, is the impoverished artisan, peasant, small tradesman. The Nazis use his language and his limited reactionary views in their mass speeches. In terse, brusque sentences the most meaningless statements are proclaimed as if they were unshakeable natural laws: “Woman belongs in the home! The peasant is the vital source of the Nordic race! The Jew is to blame for everything! Marxists are subhumans!” This canon of Nazi wisdom is repeated untiringly until the brain reproduces it in sleep, like the Bible sayings that are drilled into children. That is how “faith” is bred.

Simplicity is aided by imagery. The untrained person does not think in concepts, but in images. How easily remembered was the 1932 promise of revenge: “Heads will roll!” How skillfully the agents of mass impoverishment select the tone to conjure up before the unemployed a community of interest with the parasites: “We shall restore the good old pea soup to its place of honor!” With this appetizing image the impairment of the people’s nutrition, the monotonous mass feeding in the labor camps, are portrayed as achievements.

And then the genuine colloquialness! Even a speech most hostile to the people’s interests wins the naive listeners when it is studded with unconventional idioms taken from colloquial speech, when it leaves the rut of official and literary speech and adapts itself to the level of the uneducated listener. Goebbels is a master of the Pied Piper method: speeches interlarded with Berlin slang, jokes, etc. And the other Nazis have learned from him.

Above all, the language must be emotionally stressed! Exuberant emotionalism serves to blur lying false conclusions and poverty of thought. In his big Sportpalast speeches Hitler cries at certain points or gnashes his teeth with anger. Emotional anger. Emotional outpourings in language have just as suggestive an effect as this pantomime. The superlatives of emotionalism dominate. When an officially recommended book bears the brilliant title Germany, Germany, nothing but Germany, and when the Storm Troopers must sing We fight for Germany, for Adolf Hitler we die—these are the highest stages of chauvinist and “Fuhrer” psychosis. They alternate with outbreaks of mortal hatred of Marxists and Jews.

Just as important a factor is the deliberately (one might say: emphasized) sloppy sentence structure. Contempt for reason, for the simplest laws of logical thinking, is implied in the neglect of any sort of sentence construction. The frequency of these offences proves to be symptomatic. Let us take at random one speech out of many. The Bavarian Minister of Education, Schemn, emphatically proclaims: “We are on the road to aggregate the German people into one closed community of will, and now that we have fortunately eliminated (!) professions, castes, classes, parties, opinions, economic and other divisions, and are about to eliminate the last vestiges, we shall not let this community be separated again by anything, not even by religious beliefs!” (National-Zeitung, Essen, Oct. 23, 1934). Such nonsense, which any schoolboy could refute, is the substance of most of the ministerial speeches.

But language demagogy can take an altogether different turn. Let us not forget that socialist ideas have been diffused in Germany for decades, nor that the Communist Party of Germany had a following of millions. For all the clear or unclear revolutionary circles the fascists speak the language of the Rote Fahne. Thus Goebbels chose the following for his Angriff: “For the exploited, against the exploiters!” Thus they coined the slogan: “Down with the money bag dictatorship!” Pseudo-revolutionary phrases such as the following characterization of a speculator, who “relying most shamelessly upon his well-stuffed moneybag, insults working fellow-Germans in a disgraceful manner, derides the toiling population, which alone makes possible all of his luxury,” are scattered throughout the Nazi newspapers. Nor do the fascists shrink from direct plagiarism of Bolshevik quotations. Who does not know Stalin’s saying: “The foreign worker and specialist must understand that work in the Soviet Union is something else than under capitalism, that it is not only a source of existence, but to a far greater degree is a matter of honor, of fame and of heroism.” And in the Voelkischer Beobachter of April 11, 1934 we read: “The National Socialist sees in work not solely a means of earning money. For him work is first of all an obligation of honor towards his people.”

The menace inherent in revolutionary language was clear to the men behind the Nazis, the big industrialists. Since the 30th of June such phrases are passing into the background more and more, but they haven’t disappeared entirely. The Nazis, like so many others, have learned from the social democratic leaders that revolutionary speeches now and then can be extremely useful without imposing any obligations. But the situation is growing more and more acute. The more clearly the fascist deeds expose their socialist speeches, the more desperately must the Nazis hold fast to their phrases of “making the people happy.” They must, and they will, be shipwrecked on this contradiction.

Trash is Trumps!

Who could have expected anything else! All the writers who are really masters of the German language are either refugees abroad or imprisoned in the concentration camps and jails. The best works of German literature were burnt on book-pyres. The road is now open for all the incompetents and sycophants. During the first year of fascist rule a flood of “national” novels, as Shallow as it was broad, swamped the book market, so that the Nazis themselves were compelled to admit the shamefully low level of these productions. The books follow the well-worn track of dime-novel literature. Uncritical glorification of the existing state of affairs; no realistic description of all. The mendacious, stenciled portrayal corresponds to a faded, hackneyed language. It is a matter of course that the heroes in the latest, officially recommended novels are all called “Egon vom Steiffeneck” or “Rideger von Riedwege,” all sons of the landed nobility. They all have “beautiful, slender, strong hands.” The sole innovation, compared with the novels of Courths-Maler and Co., is the “coordination” of the costumes and the stenciled transference of the action to the present. The language of the lyric poets is worse, if that is possible. What is printed as poetry in magazines or book in Germany today—these hackneyed paens of war and horrible patriotic rhymes—represents a seriously low level of German language usage, because this alone is considered exemplary literary speech in present-day Germany, because there is no positive counterweight.

Is there really no such counterweight? Aren’t there any educated, talented fascists? Haven’t they also coordinated a few noted writers? Isn’t there a possibility of maintaining a high language level? There is no such possibility, or if there is, only to a negligible degree. It is not by chance that the greatest and best stylists of an epoch always play the role of its most incisive accusers, whether we take the young Luther, Lessing, Voltaire, Marx or Ossietzky. Striking, living language is bound up with the proximately social content that corresponds to objective reality. The clarity of sentences reflects the clarity of thought.

But wherever it is a matter of precisely not portraying reality, not speaking the truth, but avoiding and preventing thinking, as in fascist Germany, even the most brilliant pens must grow rusty. A few examples of this necessary decay of language, which is the sequel to cowardly political turncoating, can be found as early as 1933. Say, Erik Reger, who critically portrayed the trust policy of heavy industry in sober, precise language in 1929, and who scribbles Rhine romanticism in 1933, with aphorisms and stylistic pearls such as the following: “Whoever doesn’t come from the Rhine, is only half a man,” or “This unrequited love of the landscapes (!) gave him food for thought.” (Since when can landscapes love in vain?) Or, “Along the Rhine characteristics are always inherited from one’s father,” and the like folk language. Here the “national rejuvenation” has already borne fruit! The sudden drop in language level is a typical phenomenon in German literature and the German press today. Since content is the ultimately determining factor in the mutual interrelation of form and content, the development of literary language must finally lead to inflated pathos, false primitiveness, or colorless trash even in the talented coordinated writers.

Colloquial Language

For lack of space we shall confine ourselves to the barest outlines. Whereas cursing and coarse language are combatted in the factories of the Soviet Union, thus systematically raising the level of the proletarians’ and peasants’ colloquial speech, the fascist mass organizations are actually aiding in the spreading brutalization of the people. Take for example, the realistic reproduction of typical conversations in Storm Troop barracks and nationalist terror organizations to be found in revolutionary proletarian literature, as in Ernst Ottwalt, Walter Schonstedt, and others. The world of the trenches comes to life again or is taken for granted in this coarse army speech. The militarization of colloquial speech has become so widespread that it is even too much for the stomachs of old professional soldiers by now. A section chief of the Reichswehr Ministry, Major Foertsch, writes disapprovingly in the Hamburg Fremdenblatt of Nov. 12, 1934:

“The soldier sees with uneasy feelings how military terms, formulas and concepts are being more and more used in the speech and written language of the civilian, even where they are unsuited to the matter in hand. They ‘exercise’ what they can practise and train. They ‘advance’ and ‘break in’ where they aim at success. They see ‘breaks in the front’ where they recognize defects. They ‘put in shock troops’ where they want to eliminate mistakes. They make ‘training grounds’ out of their field of activity…”

A few dozen unpleasant curse words play a major part, alongside the slogans of the day, in the miserable vocabulary of the brown hordes. There are numerous expressions for murder—for very good reasons: “knock cold,” “lay flat,” etc. This language betrays the degeneracy of emotional life, as well as the incapacity for logical thinking and objective discussion.

The barbarism that fascism has brought with it in all fields of cultural life, also takes possession of its most elementary expression, language. The significance of antifascist literature is therefore still greater—here alone is the heritage of the highly developed, rich German language conserved, until the time when there will again be a language culture in Germany as well.

Translated from the German by Leonard E. Mins

Literature of the World Revolution/International Literature was the journal of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers, founded in 1927, that began publishing in the aftermath of 1931’s international conference of revolutionary writers held in Kharkov, Ukraine. Produced in Moscow in Russian, German, English, and French, the name changed to International Literature in 1932. In 1935 and the Popular Front, the Writers for the Defense of Culture became the sponsoring organization. It published until 1945 and hosted the most important Communist writers and critics of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/literature/international-literature/1935-n04-IL.pdf