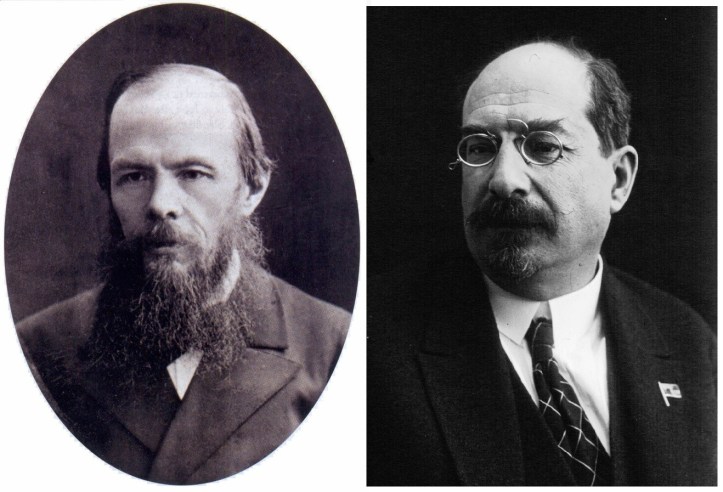

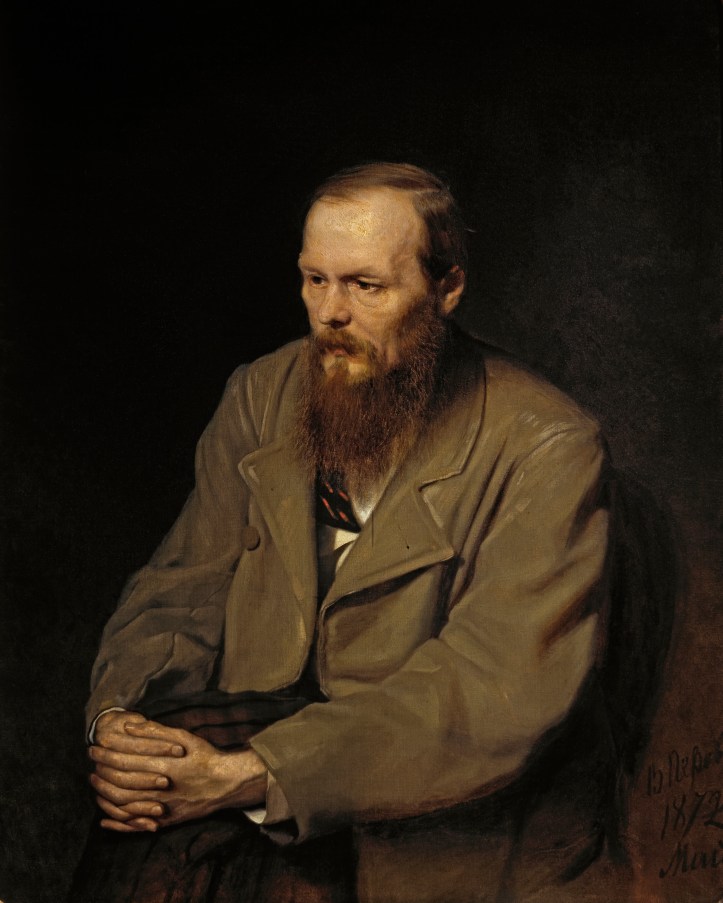

Dostoyevsky’s impact on literature, Russian and world, is incalculable. Lunacharsky speaks to that which is specific and general to the class-position of the great 19th century Russian novelist.

‘On Dostoyevsky’ by Anatoly Lunacharksy from International Literature. No. 5. 1933-34.

Marxian criticism, which occupies itself considerably with Dostoyevsky, has taken up the question of the class genesis of his work. On the one hand the opinion is expressed that Dostoyevsky, in distinction to the writers of the aristocracy, is the first great writer of the middle class, the poet primarily, of the unfortunates of the city, their sufferings and strivings. On the other hand, there are many indications and expressions of Dostoyevsky himself, that would place him as a representative of the decadent aristocracy. From this point of view Dostoyevsky is brother to Pushkin, who was also the representative of the aristocracy decadent in its time, although not so impoverished yet and discouraged as the aristocracy of the period and the circles that interested Dostoyevsky, and Turgenyev, who reflected the displacement of the aristocracy, and Tolstoy, who experienced the storm of protest against advancing capitalism, that raged in the stable, rural Russia of the country gentleman. On closer scrutiny however, it must be admitted that this question is by no means of great importance. Dostoyevsky’s first works are undoubtedly devoted to the small man of St. Petersburg, and the nobility plays no role there whatever. In the novels there are many hints at the former greatness of this or that hero or personage in these philosophical works, however, each time we find we have to do with a nobleman unprooted, turned into a city tramp, a government official, an undefined city pauper, or at times, an adventurer. How far Dostoyevsky himself saw that this kind of nobleman had merged with a new class of society, the new middle class which was made up of the old middle classes, ruined merchants, ordinary citizens and denobled noblemen can be seen from the fact that in a letter to Katkov he speaks, for instance, definitely of him several times as the descendant of a once noble family.

Tolstoy reflected the disintegration of the old order in the country, among the landed gentry. Dostoyevsky reflected the same process in the city. That is his chief significance as a writer. In this reflection, what came to the front was naturally, as might be expected for that time, not the proletarian and capitalist, but the figures that stood closest to the typical intelligentsia, the city’s poor on one hand and the professional intelligentsia on the other. These are the strata of the middle class whether descended from a lord of the manor or retaining some of the traits of a nobleman.

The whole of this city population, created to a great extent by capitalism (at first by the growth of mercantile, then industrial capital) suffered or at any rate was tossed about in the atmosphere of the advancing capitalist order or, to be more exact, capitalist disorder. Great writers are generally born in the wombs of great crises; they reflect all the colorfulness and all the restless dynamics of the crisis, and the mainspring of their work is their anxiety to find some kind of solution, a consoling answer to the burning questions of life.

Discussions are also taking place as to the kind of middle class that Dostoyevsky represents; was it a decadent middle class, i.e., a class without perspective–then its exponent should of course be a dark pessimist. It is obvious that the representative of such a class can seek escape from his pessimism only in bitter cynicism or in mysticism. But can the middle class of the seventies-eighties (in Russia-trans.) be considered decadent? Did not capitalists rise from its ranks, was not this middle class goaded by a thirst for profit, by wild careerism, by a passionate desire to live like the rich, by readiness to do anything and everything in order to achieve success, in a word, imbued with the lust of life? Such a class can not be called decadent, a growing bourgeoisie is not decadent; we may not sympathize with its aims, its course, but we must admit that in the beginning of its reign it is a powerful and even peculiarly creative class. And finally, everyone knows that the middle class of the period gave birth to a group of populists including such real figures as Chernishevsky and Dobrolubov. Yes, and Pisarev can hardly be called a decadent.

The fact of the matter is that all these three varieties of middle class existed at once, as one class, and at times the frame of mind of all three could be contained in one breast, in a single person. A successful member of the middle class created a cynical philosophy for himself, decided that everything is permissible, became a man of affairs, a merciless profiteer. Dostoyevsky knew this, portrayed these people and detested them. Not only that, but even the desire for happiness generally which lived mightily in even such a person’s heart, Dostoyevsky tried to besmirch, claiming this desire to be part and parcel of the inhuman egoism of these detested rising or risen bourgeois. This desire for a fuller happiness, this lust of a new class for life, particularly strong in the ordinary citizen of the time, might lead not to the pursuit of personal profit, but to struggle with the general chaos, by organizing an orderly society, by struggle against rising capitalism by becoming a weapon of socialism. It was thus that a sympathy for Utopian Socialism arose in the best of the bourgeoisie and the most energetic in mind and will became revolutionists of the type of Chernishevsky, whom we gladly recognize as the direct and worthy predecessors of our great revolution.

Dostoyevsky knew about this too. People of this type attracted him powerfully. In the beginning of his career he joined the circle of Petrashevsky and not only was he captivated by Utopian Socialism (Fourierism) but developed truly revolutionary enthusiasm and declared himself several times that the existing barbarous order should be forcibly overthrown. But even if Chernishevsky at times spoke bitterly of the fact that at that period this road was bound to lead to defeat, and at the end of his life after imprisonment and exile told the sombre story of the sheep who wanted to become a goat a hint at the tragic prematureness of the revolutionary movement of the time–Dostoyevsky, in face of the furious attacks of the black forces, was unable to defend these advance posts with that unexampled dignity which we find in Chernishevsky and Nechaev. Dostoyevsky after being sentenced to death and then, the sentence commuted at the very point of execution, subjected to the tortures of hard labor and exile, was broken, or rather bowed. After a tremendous inner struggle while retaining his hatred of the bourgeois spirit he inflamed himself with a hatred of the revolutionary spirit. He tried to combine them, tried to see in the revolutionist only the haughtiness of a mind that has renounced life, only lust, attempting by crime to achieve success, in a word “godlessness” to use his terminology, the lack of conscience, love. By such an operation the revolutionist became a devil; Dostoyevsky had to throw together and condemn both the bourgeois and socialist courses in order to justify his choice of the third course, of which he was the greatest exponent.

What was this third course? This is really the course of the decadent middle class. Of tens and hundreds of thousands of tortured people, people who have touched bottom, lack any means whatever of struggle, with no hope of bettering their lot; with their only escape in suicide or a life of darkness, drunkenness, debauchery or finally in making religious peace with the world, supported by belief in another better world where they will be compensated for the injustices suffered in this.

It is among such classes that the doctrines of humility, and non-resistance thrive. Dostoyevsky tried to build a similar philosophy out of patriotic pride, pronouncing Russia a land of special atonement and suffering, and out of christianity, which had its origin in similar social circumstances, and principles like: “all are guilty,” “love is the only reaction to any evil,” “penitence is the only atonement for sin,” etc., etc. From this point of view the struggle against the autocracy could be abandoned, it could be recognized as the lawful expression of divinity, the old order that was receding, could be pronounced a blessing, and a merciless struggle declared against both capitalism and more particularly socialism as devilish temptations.

This Dostoyevsky actually did. He was not, however, inwardly certain of the final triumph of his Christian humility, theories and feelings. Quite the contrary, the revolutionist within him continued to live and from the cellar into which he had been driven, shook the walls of Dostoyevsky’s chapel with his protests. Hence the partners of “Satan”–Ivan Karamazov, Stavrogin, Raskolnikov–however he tried to libel them–came out interesting, extremely significant figures, triumphant tirades were put into their mouths (for instance the conversation between Ivan Karamazov and his brother Alexey and the famous legend about the inquisitor); while on the contrary, the proponents of love–the Sonyas, Aleshas, and Myshkins–in spite of all his efforts to lend them holiness and depth, seem rather flat, boring figures and their preachings lack all novelty or strength. Dostoyevsky himself admitted this in The Brothers Karamazov. He gave great battle to his own doubts, his own protests against his surroundings, against the whole “world” and wrote his friends that he failed to conquer these opponents of his own imagination. And besides this, in a conversation with Suvorin, Dostoyevsky admits that he is dreaming of a final part to Brothers Karamazov–the novel is far from finished: in this last part Alesha “of course” turns revolutionist.

The fundamental problem of middle class morals–shall one adopt the ways of humility or egoism, or the ways of revolution and socialism–tortured Dostoyevsky all his life. And this is characteristic of a representative of a class in which all three tendencies prevailed. With unequaled mastery Dostoyevsky portrays the intolerable conflict which arose in the people of this class as a result of the shattering of the old ties, the extreme uncertainty of the future and the extremely difficult present.

All Dostoyevsky’s work, his whole being teaches us that the only way out of the chaos of his time was through revolution and socialism. It is true that were he to have persisted on the road chosen in his youth the autocracy would undoubtedly have destroyed him as utterly as it did Chernishevsky. To a great extent it was an instinct of self-preservation that threw Dostoyevsky finally from the camp of the advance posts of the peasantry and, indirectly, the future proletariat, into the camp of the decadent middle class, which stood close in its creed to the black hundreds.

The government always had its doubts of Dostoyevsky, it understood the tremendous complexity of his psychology and philosophy. Society also, has all along understood that beneath the sombre exterior of the apostle of renunciation, the preacher of the orthodox faith and civil obedience, a martyr was hidden and a rebel who though half stifled in this atmosphere filled the works of Dostoyevsky with elements that boil with revolution, who though held fearfully in check, nevertheless succeeded in making his voice heard.

Today that part of the intelligentsia can love Dostoyevsky as their own writer, that has not accepted the revolution and tosses about feverishly under the advance of socialism, as it once did before the onset of capitalism. For the healthy part of our society, the proletarian primarily, Dostoyevsky is interesting as a colossal monument of a very important period in history, as an original and great master of emotional writing and keen analysis, and finally as the expression of those moods of disintegration and doubt to which these sound elements must not close their eyes inasmuch as they still have in their midst side by side with their Dostoyevsky–similar fellow travelers. It must be remembered that Dostoyevsky became exceedingly famous in Western Europe; at present, during the crisis this fame has still further spread. This is because the middle classes there are living through a period of tremendous disintegration. Thus we must know and understand Dostoyevsky, because the spirit of Dostoyevsky is still alive, is still developing in the consciousness of the intermediate classes.

Literature of the World Revolution/International Literature was the journal of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers, founded in 1927, that began publishing in the aftermath of 1931’s international conference of revolutionary writers held in Kharkov, Ukraine. Produced in Moscow in Russian, German, English, and French, the name changed to International Literature in 1932. In 1935 and the Popular Front, the Writers for the Defense of Culture became the sponsoring organization. It published until 1945 and hosted the most important Communist writers and critics of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/literature/international-literature/1933-34-n05-IL.pdf