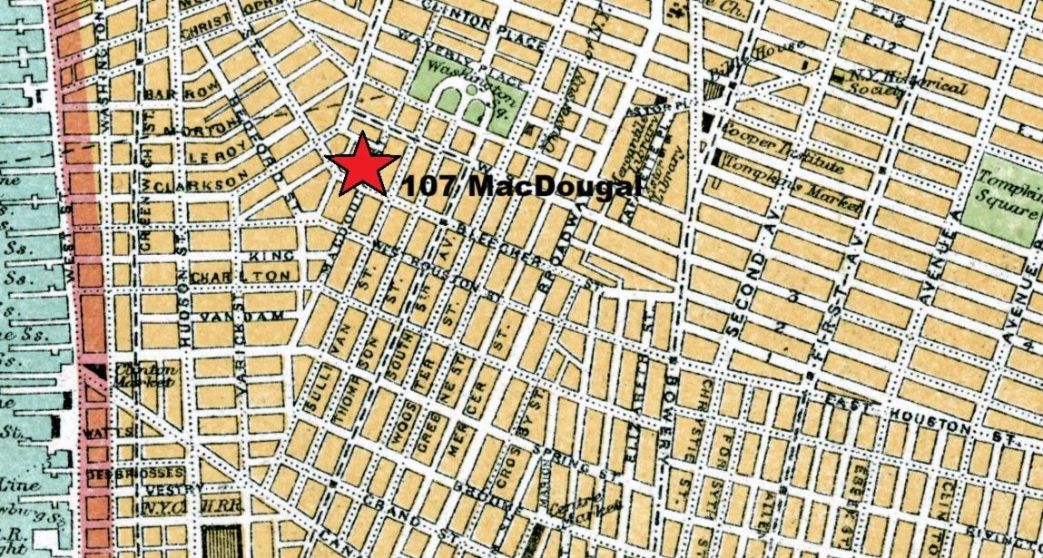

With nearly 400 members centered on Manhattan’s Little Italy Neighborhood, an internal report on reversing the stagnation of Communist Party’s Lower West Side unit, with headquarters at the Workers Center at 107 MacDougal St.

‘Little Italy: The Life of a New York Unit’ by Unit Organizer from Party Organizer. Vol. 8 No. 4. April, 1935.

Unit 32, Section 1

ON THE BASIS of seven months’ experience as a unit organizer, I wish to give the following discussion on unit life for the purpose of exchange of experience with other unit organizers:

Unit 32 had done some very good work in its concentration task, unemployment work in Little Italy. It had established a workers’ club and an Unemployment Council Local.

But at the time I became organizer, the unit was in a rather bad condition. Our best forces had been taken out to form a waterfront concentration unit. A short time before that, there had been a bad inner situation which had left unhealthy after-effects, and the comrades were quite demoralized. Out of a membership of 385, only 8 showed up at a unit meeting the first week. The club meeting scheduled for that week did not take place, nor did the Unemployment Council meeting, because the attendance was so poor. In general, there was a slump in all the activity in the neighborhood.

In analyzing the situation we concluded that the general activity in the neighborhood had fallen down due to the demoralized condition of the unit which should be the driving force in the neighborhood activity. Our first task therefore was to consolidate the forces and the work of the unit. For this we needed, first, a full bureau composed of active, responsible comrades. We therefore called an “enlarged” bureau meeting with several of the more responsible comrades present. Together we discussed the situation and put these comrades on the bureau.

Our Shortcomings

We found that our chief defects were:

1. Lack of systematic planning. The bureau meetings were neither thorough nor frequent enough. Assignments were made haphazardly without picking the best-suited person for each job. One week’s work seemed to have little to do with the previous or following week’s work.

2. Lack of political clarity. The comrades did not understand the importance of their assignments, and the work seemed mechanical and meaningless. For these reasons, too, unit meetings were long and boring.

What Kind of a Unit Do We Want?

After determining the defects of our unit, we discussed what a unit should be and these are the conclusions we came to: A unit should be:

1. The organizational center of activity in the concentration territory; the place where you get assignments and instructions.

2. A class-room where you get organizational information and political guidance; the place where you learn the historical function of the movement in general and your unit in particular.

3. A source of enthusiasm.

How did we go about accomplishing these aims?

To make the unit the organizational center of the neighborhood activity, we assigned certain comrades to have the Club as their main work, and others to have the Unemployment Council Local as their main work. This was done with the cooperation of the Italian District Bureau and the Section Bureau. They helped us both in selecting comrades and in laying down the policy. In this way the two mass organizations built up by our unit were getting Party guidance through the unit and yet the whole unit was not acting as the fraction of both organizations as it had been doing. This left the unit time and forces to carry through other activities.

As for making the unit a class-room, here we are just beginning to make headway. Agitprop work as we see it, consists of the following:

1. Political discussions in the unit. Through these discussions we can broaden and extend the political vision of our Party members so that they can see their day-to-day work as part of a tremendous world historic movement.

2. Politicalizing assignments. No matter what assignment is given, whether it is visiting a Socialist Party branch for the united front, or distributing leaflets for a mass meeting, the significance of the task is pointed out. Therefore, the comrades feel that they have a responsible task to carry out instead of feeling that they are doing something because they must.

Our agitprop work on the whole is not very good. Our more advanced comrades have not yet reached the point where they can help the more backward comrades in their development. The result is that discussions are usually left to a few comrades. This is bad, first, because we are not developing new forces to take initiative, and second, because even our more advanced comrades are not sufficiently developed to lead a really good discussion. This lack of theoretical development is at the basis of every weakness in all our work.

What are we doing to remedy this situation?

1. Three of our comrades attended the last term of the Section functionaries’ class.

2. This term we plan to send two comrades to the Section functionaries’ class, and two rank-and-file comrades to a beginners’ class at the Workers School.

3. In the unit we hold political discussions every week, calling in comrades from the outside when advisable. For example, we had a comrade from the Italian Bureau discuss Italian fascism at one unit meeting. Another time we had a comrade from a shop unit in our territory discuss shop work. Another time we plan to have a comrade from a waterfront concentration unit lead a discussion on marine concentration.

4. We are establishing the practice of holding political discussions not only in the unit, but at the bureau meetings. The second half of each bureau meeting is a study circle.

Now as for making the unit a source of enthusiasm—this is very important. Too often our comrades take their assignments, carry them out most of the time, do their work dutifully but with no enthusiasm. They seem to understand the necessity for Party work, but they are not aware of the power that belongs to them as organized, class-conscious workers. And here, we, the unit functionaries, must understand that it is not enough to make the comrades understand the necessity for everyday routine work, not enough even to make them realize the political significance of this work, but we must dramatize this work so that the comrades will not carry out their work mechanically, but like proud leaders heading for victory.

We must make the comrades see the colorful, dramatic aspects of their routine duties. For example, not long ago we elected a new bureau. Instead of going about it in a matter-of-fact way, we spoke of it for two weeks in advance, regarding the matter of elections as a rallying point for future work. When the election meeting came, the bureau did not simply bring in its proposals, but came prepared with an analytical report of the unit’s work for the past six months, pointed out the shortcomings and the lessons, and discussed the perspectives for the next six months’ work. We endeavored to make the comrades see that the work of our unit is important work, and to make them approach it as seriously as the leading comrades approach the preparations for a Party Convention or a Plenum. In this way everything we undertake can be dramatized. The workers in every unit, in everything they do should be made to realize that when they are doing routine duties, they are making history.

Our Accomplishments and Methods of Work

In this manner we have tried to work. It goes without saying that we have made many mistakes, but we are learning from them. These are our accomplishments:

1. We have organized a youth club of some 35 members.

2. We are in the process of organizing a children’s group. We now have about 16 youngsters who come every Saturday.

3. We have drawn a large number of Italian women into the Unemployment Council.

4. We are publishing a street paper, with some articles in Italian.

5. We carried through an active election campaign, where in spite of the many shortcomings, we more than doubled the Red vote in our district.

6. We recruited about 20 workers in the last two weeks of the Drive.

Now, what are the specific methods we used in tackling our organizational problems?

1. A well organized, loyal, conscientious bureau that meets regularly and takes up unit problems in detail, plans assignments in advance, selecting the proper comrade for each assignment, instead of depending on volunteers and wasting time at unit meetings.

2. A knowledge of the unit membership. A new member is asked to remain after his first meeting in the unit, the organizer interviews him, finds out what his occupation is, what are his inclinations, his mass organization activities, how much time he can give to unit work, etc.

3. Systematic planning. This means not only planned unit meetings, but also a complete plan of work with control tasks for every campaign; an analysis of the work after the campaign is ended; and a careful check on the plan of work during the course of the campaign.

4. Attention to the comrades active in mass organizations. In every unit there are several comrades whose main work is in mass organizations outside the unit territory. Because these comrades usually take very few unit assignments, the other comrades are inclined to feel hostile toward them. And the mass organization comrades, for their part, are practically divorced from the life of the unit and do not feel themselves part of it. We are remedying this situation to some extent by calling these comrades into the bureau, discussing their work with them, and having them report at the unit meeting on their mass organization work. By doing this we accomplish the following: a. We check up on these comrades. b. We break down the antagonistic feeling because we all realize that these comrades are doing Party work, even though not directly through the unit. c. We broaden the political understanding of the comrades by this exchange of experience.

We consider this very important because we understand the importance of healthy fractions in mass organizations, and we as the organizational and political leaders of our unit know that it is up to us to help these comrades to coordinate their activities rather than to load them with extra assignments that they cannot adequately carry out.

The Party Organizer was the internal bulletin of the Communist Party published by its Central Committee beginning in 1927. First published irregularly, than bi-monthly, and then monthly, the Organizer was primarily meant for the Party’s unit, district, and shop organizers. The Organizer offers a much different view of the CP than the Daily Worker, including a much higher proportion of women writers than almost any other CP publication. Its pages are often full of the mundane problems of Party organizing, complaints about resources, debates over policy and personalities, as well as official numbers and information on Party campaigns, locals, organizations, and periodicals making the Party Organizer an important resource for the study and understanding of the Party in its most important years.

PDF of issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/party-organizer/v08n04-apr-1935-Party%20Organizer.pdf