On the Gestapo’s ‘most wanted’ list, the great German photomontage and anti-fascist, James Heartfield’s work adorned hundreds of Communist publications of the 1930s, among the most recognizable artistic statements of the era.

‘John Heartfield’ by Alfred Durus from International Literature. No. 3. 1935.

About a Noted German Revolutionary Artist

In 1841, the following “criticism” appeared in the Leipziger Anzeiger on the subject of Dauguerrotype, that early stage in photography:

“The desire to retain fleeting pictures as they pass is blasphemy, since man is made after the image of God, and God’s likeness should not be recorded by any man-made machine.”

In 1934, the German and Austrian Embassies in Prague, united in wailing against Heartfield’s photomontage which was on show as part of an international exhibition of caricatures organized by the “Anes,” association of artists.

On one side in Germany, Heartfield was reproached with disparagement of Hitler, and on the other, in Austria, with insulting the representatives of the Austrian emblem. It infuriated the representatives of these two countries to see how the artist portrayed, with such aptitude, the executioner’s axe of Germany and the hangman’s noose of Austria.

1841-1934—blasphemy, executioner’s axe and hangman’s noose: similar anti-cultural expressions of reaction.

John Heartfield, a splendid artist, is at the same time a fighter of significance, struggling, persevering, straining every nerve against reaction, fascism and war. Today, among German emigrants, his work is of prime importance for the struggle against fascism.

His first photomontage work was born of a militant hatred of imperialist war. During the World War, the German military censorship suppressed every semblance of freedom of opinion. But Heartfield outwitted the censorship, by sending letters made up of newspaper clippings, photographs and drawings, arranged, of course, so as to be absolutely meaningless to the censorship officials.

He has retained the original political aggressiveness of his early letter-montage. He has since developed to a higher level both artistically and politically.

An Artist to The Masses

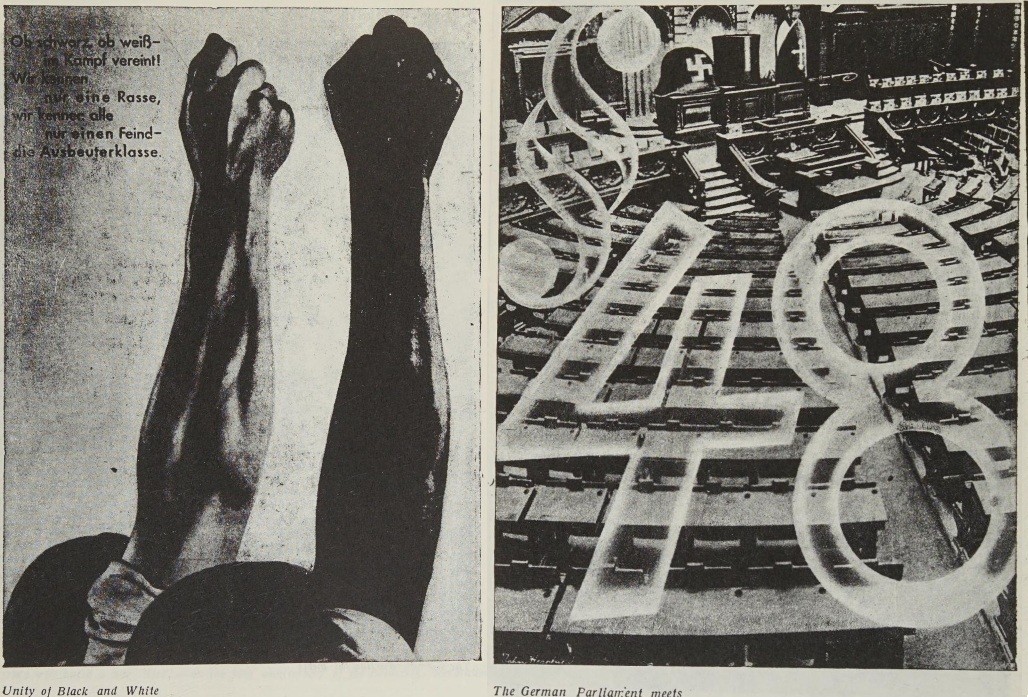

Heartfield is one of the most popular revolutionary artists of Germany. His greatest merit lies in his capacity of impressing the masses. He is always endeavoring to raise the political effect of his work by the use of bold, unusual, surprising and striking elements in artistic forms.

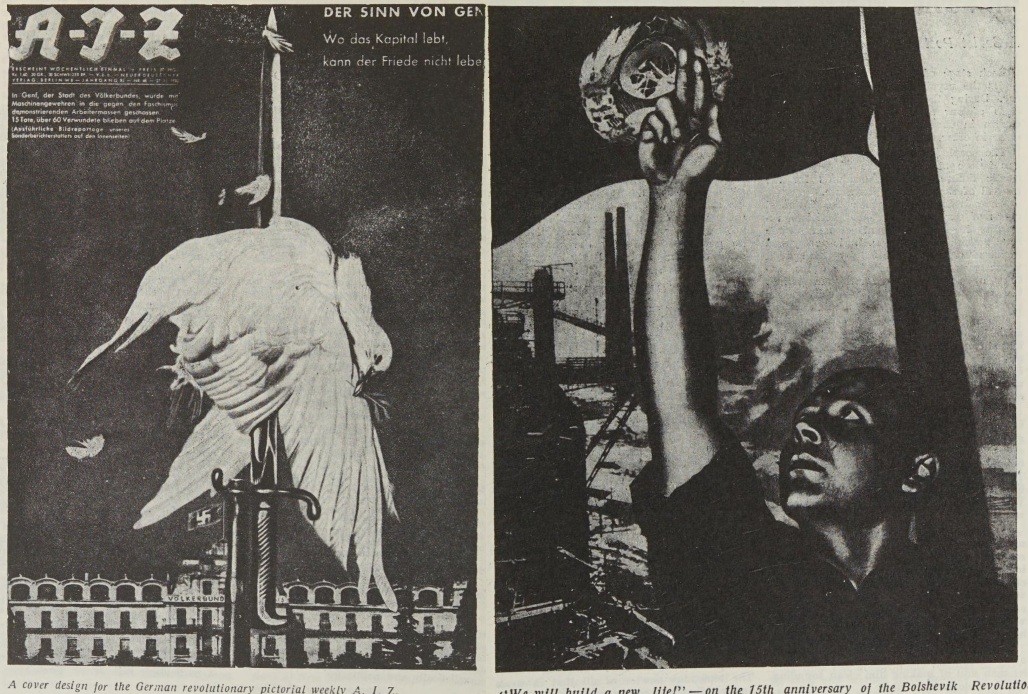

What German worker does not know this one or that photomontage by Heartfield—the “Cabbagetop,” the elegant gentleman with the stand-up collar and tiger head, the war hyena with the order “Pour le Profit,” or the arrest of Karl Marx by the former Berlin chief of police Dorgiebel? All these pictures have appeared in AIZ, illustrated weekly of the German proletariat.

Heartfield won great merit also as a pioneer of his own kind of book-jackets for the “Malik” publishing house, as a designer of very effective revolutionary pamphlet covers, as scenic artist, etc.

With the simplest methods, he was able to produce tremendous effects. This “simplicity” was always an artistic richness, it was never meager in idea or artistic quality.

Could there be a more appropriate emblem of fascism than his well-known swastika, a “simple” mounting made of executioners’ axes, of “blood and iron?”

Or the gifted revelation of social-fascist pacifism as shown in “Dalliance of a Pacifist Angel.” The “winged” social-democrat Breitscheid, fixes a cannon with a dog muzzle and says: “Now go on, shoot.”

Heartfield’s satirical photomontage is always born of authentic political incidents and these are shown with truthful reality. There are few satirical artists today whose work can vie with the political aptness, the abundancy of theme, and the deep content of Heartfield’s photomontage. In his art, he continues the creative inheritance of such great satirical artists as Hogarth, Goya and Daumier.

What is most exceptional in Heartfield’s work is that he has raised photography to a particularly high artistic level.

Literature of the World Revolution/International Literature was the journal of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers, founded in 1927, that began publishing in the aftermath of 1931’s international conference of revolutionary writers held in Kharkov, Ukraine. Produced in Moscow in Russian, German, English, and French, the name changed to International Literature in 1932. In 1935 and the Popular Front, the Writers for the Defense of Culture became the sponsoring organization. It published until 1945 and hosted the most important Communist writers and critics of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/literature/international-literature/1935-n03-IL.pdf