The ‘Lenin of Leavenworth’ on the extraordinary strike organized by political prisoners of inmates at Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary.

‘The Fort Leavenworth General Strike of Prisoners’ by Carl Haessler from Labor Defender. Vol. 2 No. 1. January, 1927.

An Experiment in the Radical Guidance of Mass Discontent

The 3,700 men constituting the prison population of Ft. Leavenworth in January 1918 will probably remember that month as one of the most profoundly stirring of their lives. Far more than Woodrow Wilson’s hollow call to youth to save a democracy owned body and soul by the Morgan bankers, more even than the spectacle of the world at war, did the almost unanimous mass rising in America’s largest military prison make clear to its participants the meaning of unified joint action. Not every convict took part in the general strike that brought the war department of the strongest nation on earth to its knees. But those who scabbed will also remember the surging of overwhelming cooperative action that all but engulfed them too.

Perhaps 500 men, mostly white-collar jobholders and short timers, continued at their desks and flunkey tasks or volunteered to man the engine room, the ice machine and some of the essential services. These men feared to return at night to their cells where the strikers were awaiting them. They were housed in the prison auditorium on emergency beds or on the floor with a couple of blankets apiece in the dead of the Kansas winter. One was so cold that he slept in the sacramental robes which the Roman Catholic priest stored in a closet between his Sunday visits from town. The sacrilege was discovered but forgiven. Even the church did its bit toward strikebreaking.

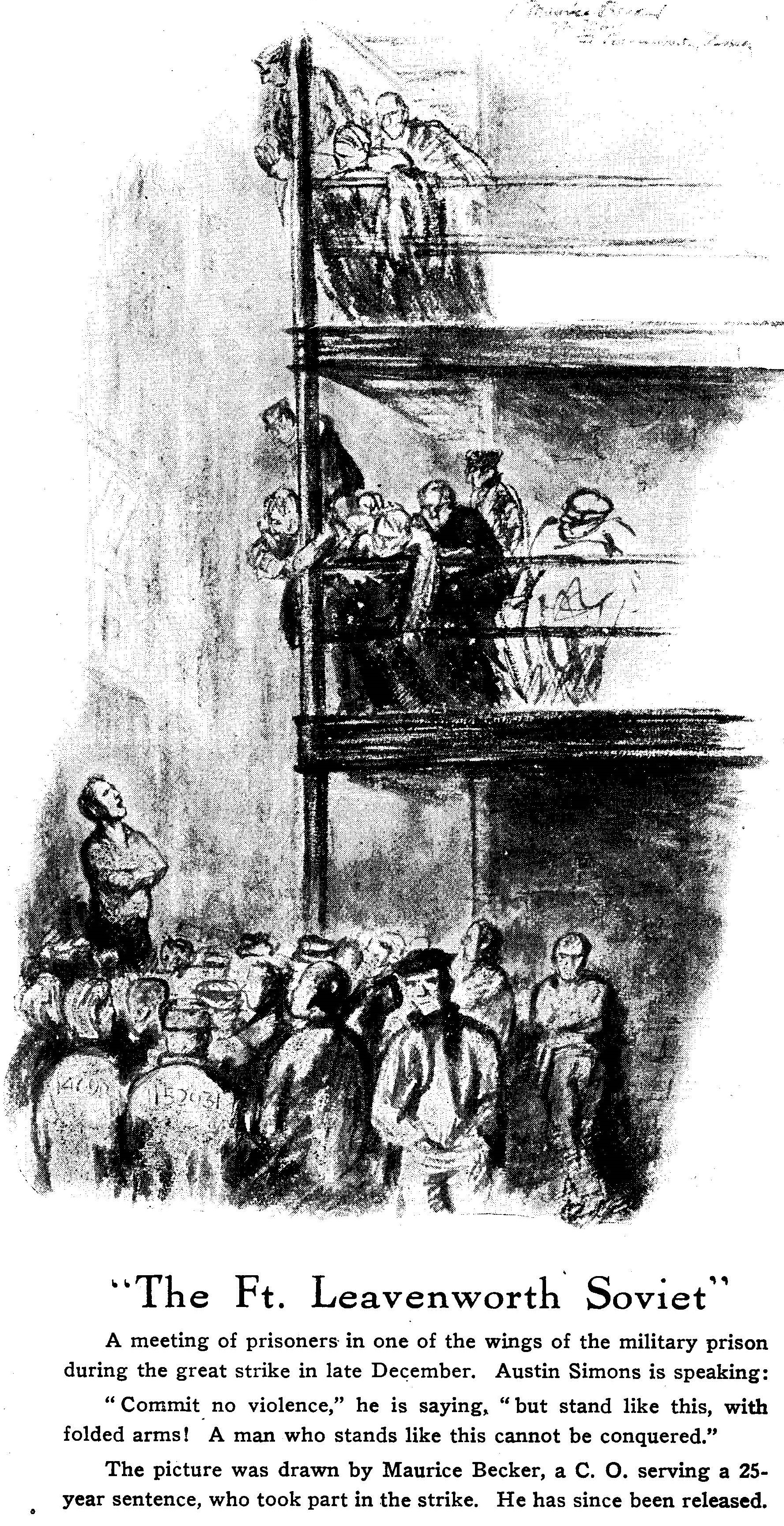

The 3,200 men on strike remained in the cell houses except those elected to the strike committee that conferred with the commandant at his request. The strikers amused themselves for the three or four days of the strike by chess and checker games, wrestling matches, swapping stories, listening to the reports of their committeemen and debating them, improvising lecture courses and in sleep. Meals were served regularly by the prison administration. The food was of better quality than before the outbreak of the strike and there was more of it. High spirits were the rule. The prisoners felt that they were on the way to victory just as the administration knew it had been beaten.

How was this feeling brought about?

It is an interesting experiment in the solidarity of mobilizing and directing mass discontent. A small but highly organized and highly conscious body of prisoners led the great majority almost without the knowledge of anybody but the leaders and their opponents, the military command of the prison. This small body of leaders were the political objectors to the Wilson war, the few score men of draft age who had gone through all the stages of the conscription process with- out being either bullied, bribed or bamboozled into becoming some part of the war machine. They had comparative freedom for their purpose after they arrived in Ft. Leavenworth from 1917 on to serve sentences of three years to 99 years or life. Their purpose was general revolutionary propaganda and, if the occasion proved favorable, revolutionary action. They had a taste of both but on so small a scale, viewed from the national perspective, that their accomplishment was only a tiny experimental one.

The political objectors found after armistice of November 1918 that they had as comrades a somewhat larger group of religious and pacifist objectors, commonly known as conscientious objectors. The politicals as a rule had no conscience so far as means of furthering their main purpose was concerned. They deemed socialism, or Communism as many of them began to call it after the Russian revolution, as more important than any specially ordained way of achieving it. So they were prepared to fight the conscience-less authorities with their own weapons. Where the commandant used spies and propaganda, the politicals did likewise and with better effect. In a few months they had the roughneck ordinary military convict tattooing red flags instead of the national emblem on their arms and chests. In some weeks more they had them rejecting every chance to shorten their terms. by applying for reinstatement with the colors.

This could not have been done, the politicals clearly recognized, without the help of favoring circumstances. The war had ended, yet the ferocious sentences imposed by stupid and brutal court martials went on unrevised. The prison kitchen, designed for feeding 1,200 inmates, creaked and strained to care for 3,700. Food became universal grouch. Cells were packed with two to 16 men. Guards were in considerable part the unconvicted dregs of the army. They had not been wanted in the combat or training units of the war machine. Officers practically likewise- arbitrary, cruel, dishonest, callous. The growing symptoms of revolt cried for leadership and the radical agitators, the political objectors, were there to supply it.

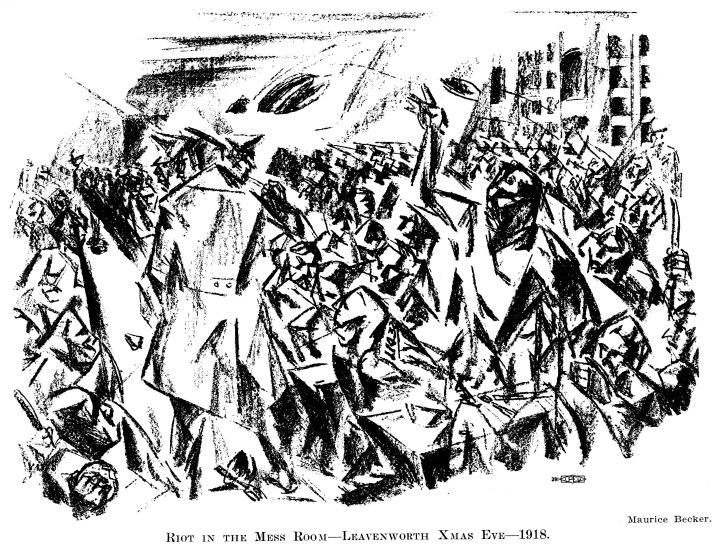

Trouble began Christmas eve, 1918. The supply of bread from the overtaxed prison bakery ran out at supper time. Prisoners who complained were hectored by a brainless captain. Soon the entire room was a chaos of yells, songs, anger and laughter. The laughter rose when officers who tried to bully the mob into silence were hit by flying raw onions and baked potatoes. The prisoners were finally led out of the mess hall two at a time and locked safely into their cell wings while soldiers with shotguns and machine guns stood guard from the gallery above.

A gorgeous Christmas dinner surprised the mob the next day. But it was interpreted as a sign of weakness in the prison regime. And disorder continued to increase.

Race riots broke out with the several hundred Negroes the victims of terrible assaults by the white “hard guys” who broke arms, knocked out teeth and bruised their helpless prey into jelly. The objectors realized that they, as the next most conspicuous minority in jail would be the next target for the spontaneous and misdirected mutinous energy of the prison roughs.

In a council of war the politicians therefore determined to supply the mutineers with a better policy and program. The general strike, with its three demands of amnesty, better jail conditions and release from solitary cells of some of the gangsters, resulted. The new policy was accepted by the gangsters, who were glad to have the help of the politicals’ intelligence and, as they believed, social and political pull outside the walls. They were glad also to find in the authorities a more worthy object of their rage.

The politicals and the gangsters working unitedly constituted practically the entire articulate and conscious elements in the prison. What they agreed on was certain to be followed by almost every one else. As a result, the military was surprised, one Friday toward the end of January, to have the prisoners stand at a unit in refusing to turn out for work. They remained in the prison yard with folded arms until they were ordered back to their cells. No attempt was made to call them to work in the afternoon. That night committees were hastily elected and secret communication established from wing to wing. Saturday morning the mutineers met the commandant. They were fully organized and conscious of their aims. There was no work that morning and the afternoon was a holiday as the prison worked on a 44-hour week.

That night the commandant surrendered. He agreed to go to Washington to present the amnesty demands, he agreed to improve the food, to reduce the number of men per cell, to increase the letter-writing privileges, to enlarge the visiting hours and rights to play or walk in the prison yard, to exterminate the bedbugs and to meet any other reasonable requests. The gangsters in the hole were brought back to daylight. He left for Washington that night.

Sunday passed quietly. On Monday the officers tried to get the men back to work but they refused to budge until a wire was received from Washington stating that all cases would be reviewed and that material reductions in sentence would be made except in cases of civil felonies, of which there were less than a dozen in the prison population. Many would be freed as soon as the papers could be put through, the commandant telegraphed. The men then returned to work.

Their strike had been successful beyond their dreams. A mere headless destructive mob had been turned into an organized, disciplined and completely unified body of men whose insistence on a single comprehensive program had been carried to victory. The political prisoners had not produced the mob but they had supplied the direction for it. The two factors cooperated in a neat little revolutionary experiment behind the walls and under the guns of Ft. Leavenworth. When the tide of events produces similar conditions on a national scale, it may be that men of national caliber will be ready to carry out a similar experiment on national, and international lines.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Not only were these among the most successful campaigns by Communists, they were among the most important of the period and the urgency and activity is duly reflected in its pages. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1927/v02n01-jan-1927-LD.pdf