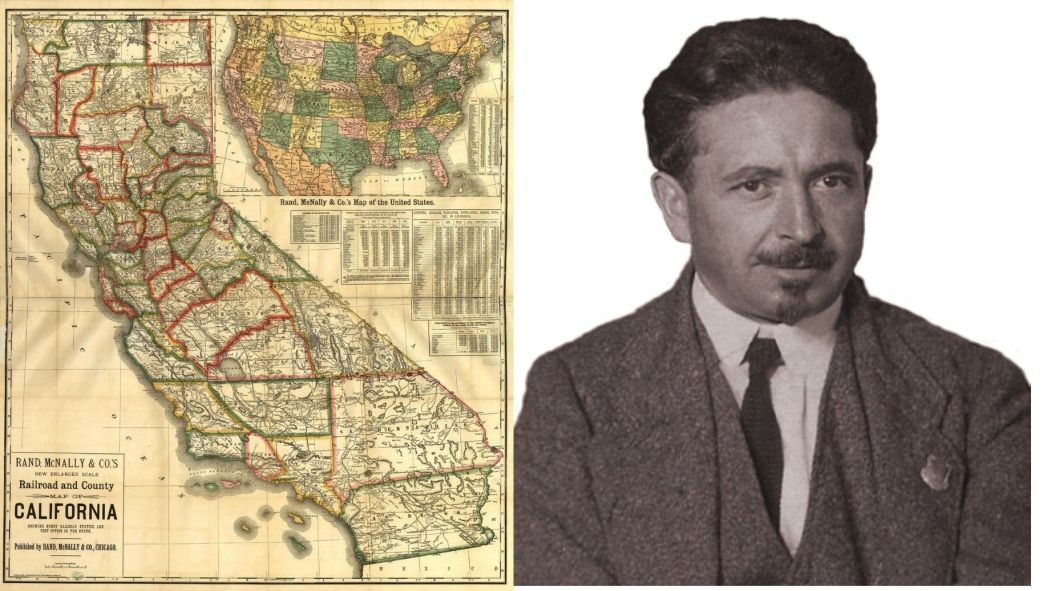

Bedacht was a German-born Marxist barber, Swiss labor leader, who later moved to the U.S. where he was a central figure of the German-speaking Socialist movement, and on the Left Wing. Moving to the Bay Area in 1913, Bedacht became editor of Vorwärts der Pacific Küste. Influenced by the I.W.W. and the specific politics of California, Bedacht was a California delegate to the 1919 Emergency Convention and a founding member of the Communist Labor Party. Written at that time, Bedacht gives a report on California”s Socialist movement, which was known for both is very middle class Los Angeles-based opportunist wing, and its impossibilist and Industrialist wing, centered in the Bay.

‘Radicalism in California’ by Max Bedacht from Class Struggle. Vol. 3 No. 3. August, 1919.

California is a comparatively young member of the family of the United States. Its development in the direction toward capitalism began only with the downfall of the Spanish colonial regime, the end of the Mexican period, and the accession of the rule of the United States. Its political life at first was dominated by the interests and the spirit of the frontiersman and the adventurer, of the men and women that pushed across the endless plains of the North American continent, conquered the snowheads of the Rockies and passed over the Sierra, challenging the forces of nature and the hostile tribes of the natives. The mixture produced by the gold fever, moreover, was hardly to the best advantage of the race. Thousands of adventurers of doubtful character followed the trail to the goldfields of California, and many a fortune of today has its foundation not in the honest toil of the men that wrested gold from the bosom of Mother Earth, but in ill-gotten gains won out of the pockets of the miners and prospectors.

During all that period there was little that resembled modern political institutions. When at length order came out of chaos, it was an order dominated and controlled by the unspeakable corruption of railroad capital. The fact that this capitalism was not a natural outgrowth of economic conditions, but was grafted upon the State, still industrially and politically unprepared for a capitalistic order, made the situation still more untenable. The rule of the six-shooter, modified by the conception of honor and morals of the frontiersman and adventurer, was replaced by the dictatorship of the Huntingtons, the Stanfords and the Hopkins. On the whole this was a transformation in name only. The six-shooter still ruled, but as a powerful instrument in the hands of an unprincipled element that was willing to do the bidding of the railroad interests and that, therefore, was invested with the powers of the state.

Slowly but surely railroad capital replaced the rule of the six-shooter by the rule of the law, devised and executed exclusively in the interest of the magnates. But in its own laboratories of profit-making the railroad interests produced the forces that were destined to break its undisputed political rule as far as this could’ be accomplished.

The colossal land grabs of the Southern Pacific could only bring the desired profits if the value of the land were tremendously increased by intensive colonization. Incidentally the increased population and products necessary for their sustenance furnished increase of the traffic to the roads. The settlers, thus imported, naturally became the enemies of the political system of the railroads. For the railroads the settlers and the farmers were simply another source of profit, while the settlers, on the other hand, considered the railroad rather as a public utility created for their convenience in marketing their products. This contradiction of interests fostered a political radicalism in the California farmer that expressed itself in the Johnsonian progressivism, woman suffrage, initiative, referendum and recall. As far as a defeat of its own objects is possible within the bounds of the capitalist political state, it suffered these defeats in California. The whole structure of the capitalist state, however, has only one object, that of serving capitalism in the pursuit of its object, profit-making. Therefore even these defeats of the railroad capital were not defeats of capitalism itself, but the establishment of a system favorable to a group of capitalist interests other than the railroads. The latter could well suffer this defeat with equanimity, for in the meantime its specific local interests were well taken care of by its local enemies. The bulk of interests lay in the field of national politics.

During the period of struggle between the settlers and farmers on the one hand, and the railroad interests on the other, the Socialist movement was introduced into California. It did not find an industrial proletariat, not even in the cities. Los Angeles is the city of retired petit bourgeois, while San Francisco is the city of the active petit bourgeois, though the latter is being pushed more and more into the background by the growing financial and commercial interests of this ideal outlet of American goods to the Asiatic world.

Thus from its very inception the Socialist movement in California was not a working-class movement, but a characteristic petit bourgeois movement. It represented not the exploited class in a struggle against exploitation, but an exploiting class against the particular form of exploitation by which it, in turn, was being victimized. It represented that portion of the petit bourgeois who saw that the evil is not so much political as economic in its nature, and that political reforms, such as woman suffrage, initiative, referendum and recall, at their best, cannot bring relief, being, at best, not more than a means by which relief may be gotten. Socialism, that is the socialization of industries by means of an intelligent use of the ballot box, therefore appealed to them. But it was a kind of post-office Socialism which was to replace the individual capitalist by the state, which the petit bourgeois hopes to control with the help of the proletariat.

The petit bourgeois character of the Socialist Movement in California was evidenced by its painstaking effort to preserve its respectability. Upon the altar of that sickening petit bourgeois respectability principle after principle was sacrificed. Not Socialist principles, but consideration of public opinion and respectability determined the course of action taken by the party. Protests against this policy were met by the argument that one must consider the psychology of the American public. They could not and would not understand that what they actually meant was not American, but petit bourgeois psychology, and that a revolutionary movement cannot make concessions even to such a formidable god as psychology. Such concessions may be made in the form of propaganda but not in the substance propagated. Any victory won at the price of a concession of the substance is not a victory, but a defeat. In California we did not conquer, we have been conquered.

The largely agricultural character of the State of California forced the Socialist movement to deal with the agricultural problem. Here again the petit bourgeois character of this movement came out. For a Socialist the agricultural problem is one that concerns the people as a whole. It is the question how the agricultural production may be organized to feed all the people. Agricultural production is not only the means of livelihood for those directly employed in it, but of vital interest to the whole population. In a Socialist state of society the problem presents itself to this point of view. But under a capitalist system of society, as a part of the great class struggle between the classes, the agricultural question concerns itself chiefly with the agricultural labor, the farm hands and the migratory laborer.

The petit bourgeois Socialist movement of California never could see it from that point of view. For them the agricultural problem was always a problem of the farmers, in most cases the owners of the farms, the agricultural petit bourgeois. The most radical expression of its agricultural program may be summed up in the program of the Non-Partisan League. Townley was their ideal of a practical Socialist.

Such policy could not be pursued without creating its natural reaction, alienation of the agricultural laborer and the migratory laborer. Instead of basing their activity upon the class struggle between exploited and exploiter, it was based on petit bourgeois reforms. The farm hand and the migratory laborer could not find in the Socialist movement the expression of their struggle but that of the struggle of their masters.

The Socialist movement in California was the first to recognize the fallacy of the ballot box as the only means of emancipation of the working-class. The migratory laborer has no political rights. He does not live in one place long enough to establish a residence, and therefore is deprived of his right to vote. The Socialist movement, if it is to be a revolutionary working-class movement, must comprise all workers regardless of their political rights, must use the political and economic power of the masses instead of relying on the voting power of the few whom the capitalist state permits to vote.

The petit bourgeois policies of the Socialist movement in California created, as a natural reaction, the anti-political-action attitude of the masses of the migratory laborers. Instead of uniting the working class it succeeded in splitting it by harnessing and hitching up that portion of the workers that possessed political rights, before the load of petit bourgeois politics, and by repudiating the many workers who are penalized by capitalist society for the crime of being compelled to travel from country to country, from state to state, in search of work, by political emasculation.

The historical events of the last two years will help to make out of the Socialist movement in California what it ought to be. Shipbuilding has been introduced as a new and ever growing industry and has created the only foundation upon which a healthy Socialist movement may be built, an industrial proletariat. These workers will gradually dominate the movement, hopelessly damaging its petit bourgeois respectability and creating in its stead the spirit of working-class solidarity. The more this spirit will crowd out petit bourgeois policies, reforms, and, last but not least, members, the more will our movement conform to the actual requirements of revolutionary activities of the working class. The movement will be built upon the organization of all workers, regardless of their political rights; it will exercise its activities in the actual class struggle for the exploited against the exploiter; and it will see its aim no more in State Socialism, but in Communism, the organization of production by all the people and for all the people.

The Class Struggle and The Socialist Publication Society produced some of the earliest US versions of the revolutionary texts of First World War and the upheavals that followed. A project of Louis Fraina’s, the Society also published The Class Struggle. The Class Struggle is considered the first pro-Bolshevik journal in the United States and began in the aftermath of Russia’s February Revolution. A bi-monthly published between May 1917 and November 1919 in New York City by the Socialist Publication Society, its original editors were Ludwig Lore, Louis B. Boudin, and Louis C. Fraina. The Class Struggle became the primary English-language paper of the Socialist Party’s left wing and emerging Communist movement. Its last issue was published by the Communist Labor Party of America. ‘In the two years of its existence thus far, this magazine has presented the best interpretations of world events from the pens of American and Foreign Socialists. Among those who have contributed articles to its pages are: Nikolai Lenin, Leon Trotzky, Franz Mehring, Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, Lunacharsky, Bukharin, Hoglund, Karl Island, Friedrich Adler, and many others. The pages of this magazine will continue to print only the best and most class-conscious socialist material, and should be read by all who wish to be in contact with the living thought of the most uncompromising section of the Socialist Party.’

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/class-struggle/v3n3aug1919.pdf