The ruling class knows that history is a weapon, capable of bringing enormous forces shaping perceptions and granting legitimacy on to today’s battlefields; it has done everything it could to prevent our class knowing about our own past. Which is precisely why stories like the one below, of intense battles fought by a militant, progressive, multi-national labor movement, remain unknown. On July 17, 1922, during the nation-wide U.M.W.A. strike, the town of Ciftonville, West Virginia saw armed combat between strikers and scab-herders. Seven union workers, twelve gun-thugs, and the county sheriff were killed. In the aftermath hundreds were rounded up and dozens sent to federal prison. Art Shields with the dramatic story and the plight of those class fighters still in jail.

‘The Battle of Cliftonville’ by Art Shields from Labor Defender. Vol. 1 No. 10. October, 1926.

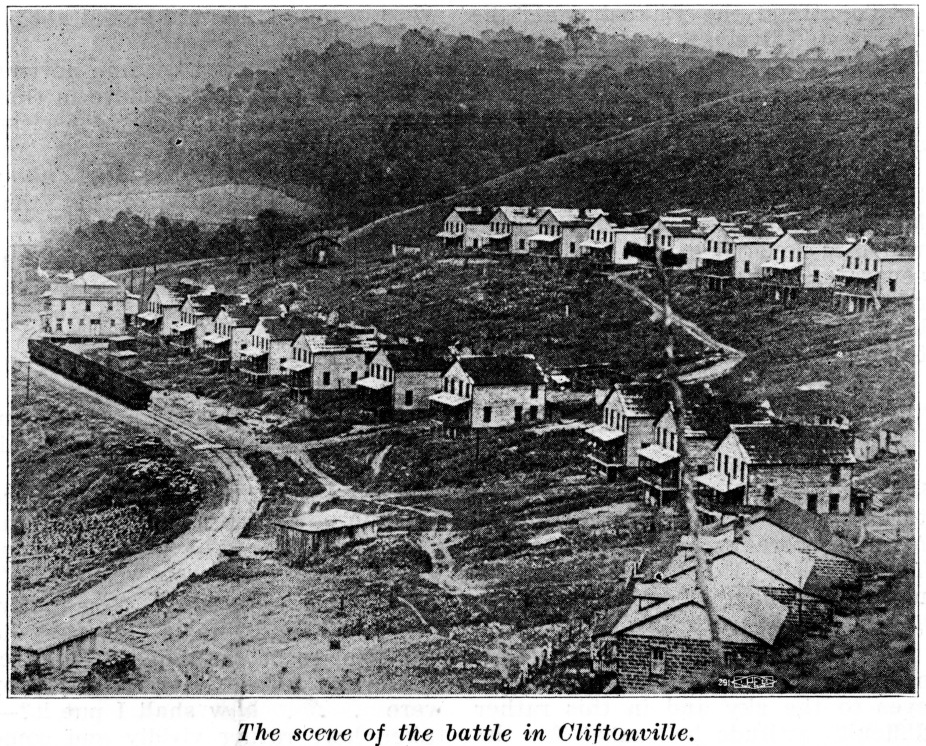

CLIFTONVILLE is a little non-union coal town on the steep slope of a hill in the panhandle region of West Virginia near the Pennsylvania border. It looks like hundreds of other soft coal towns, with rows of ragged company houses, a company store, and a long steel tipple on the hillside.

The town is very quiet now. The Richland Coal Co. mine shut down this summer and the company tenements look more ragged than ever, with window panes missing here and there.

No one would think, to look at it, that this drab, idle town was the scene of the bloodiest episode of the great 1922 strike. Yet four years ago flying lead swept the hillside for hours and the old wooden tipple that used to stand there went up in flames. Seven miners were killed in that battle and twelve company guards and the Brook County sheriff. Hundreds of union men were arrested and 43 went to Moundsville penitentiary. Six still remain there.

The battle began with the murder in cold blood of a gray-haired union picket. He was shot dead in the early dawn of July 17, 1922, when he asked a group of strikebreakers to quit scabbing. The old man with eight hundred other marchers had come from over the Pennsylvania line that morning.

To understand the spirit of 1922 it is necessary to put oneself back in that stirring year. The great coal walkout of four years ago was the finest mass movement the American working class has undertaken, with the exception of the steel strike of 1919. It began with a half million union miners and as the strike rolled over the landscape it sucked out non-unionism like a gigantic vacuum cleaner. All Somerset County to the East in Pennsylvania came out and the coke fields further west and the non-union camps of Westmoreland and Green Counties. For the first time in history the Pennsylvania coal miners presented an almost solid front of revolt. And the miners of the rest of the nation were cheered.

All out: the problem was to keep the ranks unbroken.

One morning the news reached the miners of Avella, Pa., along the Pittsburgh & West Virginia R.R. that the Richland Coal Co. over the border was scabbing. The Richland mine—though in another state—was on the same branch railroad line and its workers were neighbors and buddies of the Avella miners. They took part in union picnics and demonstrations together.

More bad news followed. The company began evicting its old employes and importing strikebreakers. The evicted families were given tent homes by the union a half mile away but the company followed them up and harassed them. Gunmen insulted the women and shoved the men off the public highway that workers had helped to build. Shots whistled by the ears of several strikers. The company hoped to break the strikers’ spirit and drive them back to the job, for the imported strikebreakers were too few and too untrained to get out much coal.

Anger and alarm shot through the 13 local unions about Avella. Anger that friends and brothers were being hounded; alarm that what one operator was getting away with on the Pittsburgh & West Virginia line might be tried out by others in the same field across the state border The night of July 16 the march began. The program was to ask the strikebreakers to stop work and the guards to desist from their persecutions, but some of the marchers armed themselves for emergency defense purposes. They covered the ten miles to Cliftonville before dawn and posted themselves in the darkness on the ridge above the scab town.

As the sky began to gray the dim outlines of tipple and houses appeared below. A scout reported guards were hidden in several long low shacks alongside the tipple.

Next a file of a half a dozen scabs appeared on the way up the hill to the tipple. To the more cautious miners it looked as though the scabs had been sent out as a decoy to bring the strikers out from cover. And so it turned out later.

A bunch of pickets started recklessly forth to appeal to the scabs.

Their comrades begged them to come back, fearing a death trap. But the pickets went on, the old grayhaired miner in the lead. He met the scabs and spoke to them.

A volley from the shacks was the answer. The old man spun around and fell dead. The other pickets ran back. Their comrades above began firing and the battle was on.

Pierce fighting lasted several hours. The gunmen were driven with losses from the shacks and from house to house in the town. The fight raged on when reinforcements came from Wellsburg, the county seat, attacking the miners from the rear side of the hill.

Sheriff H.H. Duval led a sortie and was killed. Many conflicting stories have been told of how he met his death but the pro-employer Gazette Times of Pittsburgh admits: “Sheriff Duval was killed by a bullet fired from a miner’s rifle when he attempted to rally his forces for an attack against the miners.”

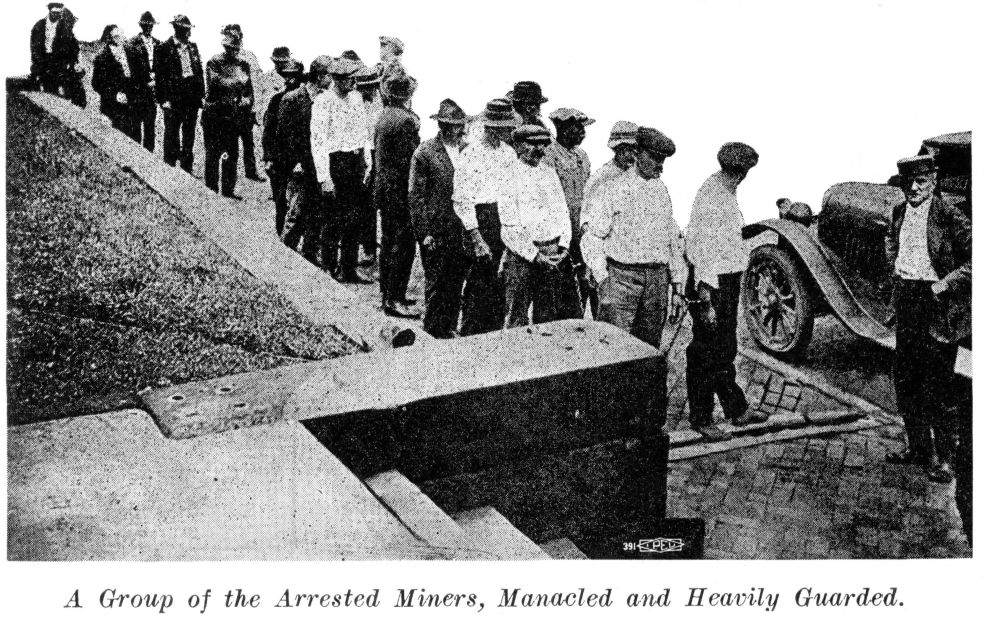

Eventually the miners retired. There would be no scabbing in Cliftonville for some time. But the forces of government had not retired and group arrests began the next day. And group convictions followed, for the Avella miners, tried in West Virginia, did not have the opportunities that the Herrin men had to get a break with the juries.

But the men were not sent up on murder charges. The facts of the killing of the picket that started the battle were too glaring. An attempt to pin a murder charge against John Kaminsky, one of the men now in Moundsville, failed. The district attorney fell back on the old vague charge of “conspiracy.”

Prisoner statistics run as follows:

Two hundred and ten men were held in Wellsburg for a month and then released.

Thirty miners got three years in Moundsville—out now.

Seven men got four to seven years—out now.

Six were given eight to ten years—still there.

These large figures show that the Cliftonville case was the biggest, in point of numbers sent to the penitentiary, of any working-class case since the war persecutions.

The six men still in the shirt and broom convict shops in Moundsville are:

John Kaminsky, single—10-year term; Joseph Tracz, wife and five children—8 years; Teddy Arunsky, wife and four children—10 years; Pete Radocowich, wife and one child—10 years; Charles Cialia, wife and six children—10 years; Frank Bodo, one child—10 years.

The legal defense of the Cliftonville men was conducted by District No. 5, U.M.W. of A. The relief is in the hands of the local unions about Avella who have a Cliftonville Relief Committee, Fred Siders, chairman. Siders, whose address is Avella, Pa., is president of the Duquesne local union. The committee furnishes each woman with ten dollars a month for herself and six dollars for each child. So a mother with five children gets forty dollars a month. Additional relief formerly came from the district union office before union finances tightened. The committee gives each prisoner directly a few dollars a month for personal expenses, whatever it can afford and all the prisoners are on the list of the International Labor Defense for the regular allowance of five dollars a month.

The loyalty of the Avella men shows all the brighter in view of the fact that only four local unions there are from working mines. And the same class conscious men hold picnics for Sacco and Vanzetti and other class war prisoners.

The Cliftonville men need more aid from the rest of the working-class and the rest of the working class needs them—on the outside. The United Mine Workers’ Union is today more desperately pressed than in 1922. It has lost half its membership in the bituminous fields. Pennsylvania and the panhandle are especially under fire and the union may be wiped out in those fields at the expiration of the 1924 agreement unless it can win by a herculean effort. Preparation for that coming battle is probably the biggest immediate issue before the American working-class. It calls for tremendous energy and class loyalty from every part of the movement, in and out of the miners’ union. And as a part of the preparation for this fight the remaining Cliftonville men must be freed—not only to get them back into the labor army but to show the world that the working-class looks out for its own and rescues its people from the hands of the enemy.

NOTE: As we go to press we are informed that all the prisoners except Joseph Tracz have been release.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1926/v01n10-oct-1926-ORIG-LD.pdf