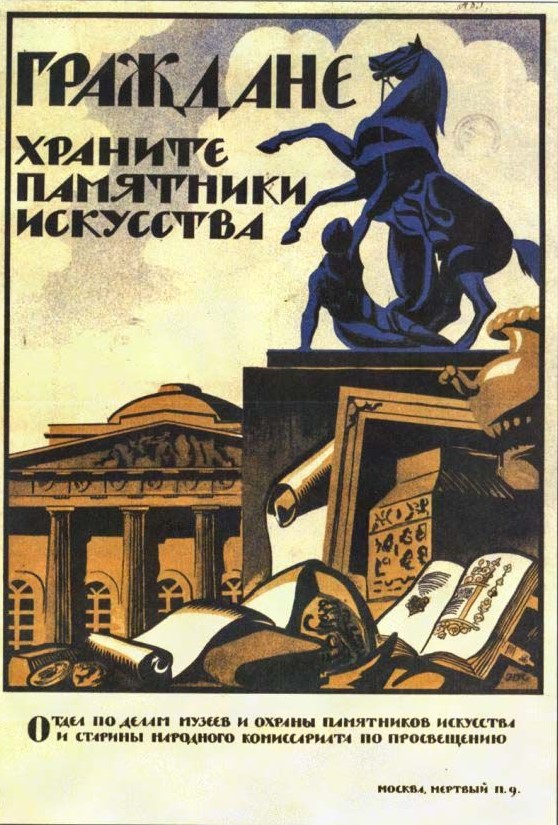

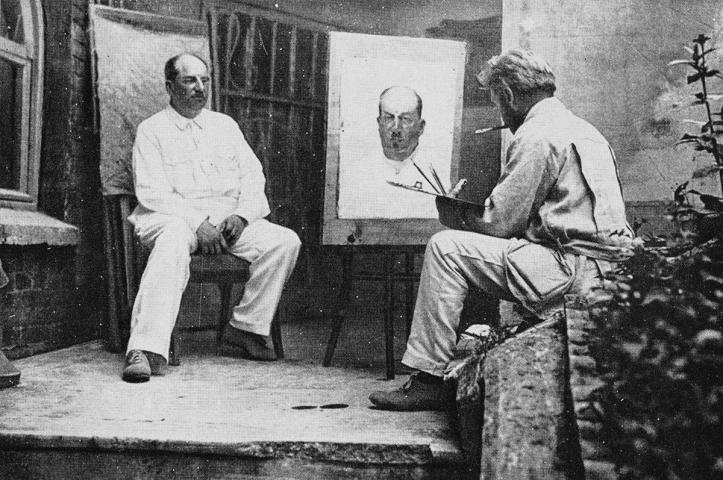

Anatoly Lunacharsky, People’s Commissar for Education, details the attitude of the new Soviet government towards the artistic heritage of the ancien régime and its preservation. Written in October 1919, comrade Luncharsky offers suggestions from our movement’s history on present attitudes over how to relate to the art of the naff nobility and monuments to our oppressors.

‘Soviet Power and the Preservation of Art’ by Anatoly Lunacharsky from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 3 No. 9. August 28, 1920.

AMONG the many calumnies that are spread concerning the Soviet power, I am made particularly indignant by the report appearing in American newspapers to the effect that we are guilty of vandalism toward museums* palaces, country homes of landed proprietors, and churches, which constitute important monuments of antiquity and frequently have a unique art value.

We can deny these accusations with pride and firmness, for we have accomplished marvels in protecting such monuments. Of course, I do not maintain that individual objects of art have not been destroyed in the course of the Russian Revolution. We have been informed of certain country Beats that have been burnt down, libraries destroyed, of collections scattered, and similar incidents, but surely it will be understood that such a mighty upheaval as the revolution could not proceed without some excesses, and we must call the attention of the imperialists to the fact that during the war that was staged by the “most civilized” bourgeois armies, human property in the occupied regions was destroyed in incomparably greater measure than in our country.

In Russia this phenomenon was of temporary nature and lasted only till the moment the Government took the reins into its hands. At present, not only in Petrograd and in its environs, where immense treasures of this kind have accumulated, not only in Moscow and in the palaces situated in the environs of Moscow, which also are unique in their class, but also in the provinces, often even in the most remote corners, we find representatives of the “Section for the Protection of Monuments of Antiquity and Objects of Art”; these representatives, with the aid of educated peasants and workers, carefully guard such property of the people as has artistic value. American newspapers have dared to speak of plundering and disorder in the imperial palaces. I should be very happy to be able to show some foreigners what is actually being done at present in these palaces — and we did to be sure pass through a serious period when all sorts of armed forces were making Gatchina and Tsarskoye Selo unsafe, when there were no supervising organs in Petrograd at all. Under these circumstances it necessarily appeared to be a hopeless undertaking to protect the treasures of the palaces and museums which are of immeasurable value even if considered only from a material standpoint. The task was rendered more difficult by the fact that many palaces, particularly the Winter Palace, had cellars that were chock full of wine, brandy and cordials. We were obliged to destroy these stocks of liquor ruthlessly, as the excesses of drunkenness would otherwise have spread to the Eremitage and to the halls of the Winter Palace, and might have caused unheard of damage. There is terrible temptation in alcohol, and I remember one good soldier of the Pavlovsky regiment who, together with certain other guards, had not been able to refrain from tasting the wine, hundreds of thousands of bottles of which he was guarding; in extenuation of his act he later said to me: “Put me alongside of an open chest of gold, and I will not touch it; but it is impossible to stand alongside of this wine,” And yet we have managed, by destroying this wine, by applying the severest measures, to prevent the misfortune that was then threatening.

If you enter the Winter Palace or the Gatchina Palace today, and find any traces of destruction in these places, you may be convinced that they are traces of the period when Kerensky and his young imperial cadets and Cossacks were still carrying on there. But there are practically no such scars remaining; we have already healed them.

As for the museums, they are in excellent order, in the hands of the best custodians. The museums have been much enriched by transferring to them works of artistic and historic value, of the most varied kinds, from private palaces and estates. While the best pictures of the old Hermitage were transferred to Moscow by Kerensky and are there waiting, packed in their crates, for the day when we may feel absolutely safe in Petrograd, the apartments of the Hermitage are being filled anew with wonderful works of art, partly purchased, partly taken from private store- rooms, which were formerly inaccessible to the public, and which now are being exhibited there. What marvelous works have been discovered and, at present, exhibited to the masses of the people and to school children in the palaces of Yussopov, Stroganov, and elsewhere!

The palaces themselves are devoted by us to the most varied purposes. Only a few among them, such as the artistically uninteresting Anichkov Palace and the Marinsky Palace, have been placed at the disposal of the authorities. But the Winter Palace has been transformed into an art palace. In its magnificent salons, constructed by Rastrelli and his pupils, you will always find a crowd of people listening to excellent music performed by the State orchestra or the State brass band, or enjoying cinematographic exhibitions or special dramatic performances.

One exhibition here follows upon another; some of them have really been magnificent both in the number and beauty of the works exhibited. It is our effort to make both the exhibitions and the museums real sources of culture, by combining them with lectures and attaching instructors and guides to every group of visitors. By separating certain collections of moderate size from the museums, and establishing separate exhibitions, such as Buddhist religious art, or the funeral customs or funeral superstitions of the Egyptians, we create a splendid means of object instruction, and such exhibitions are visited in our much tried Petrograd by masses of interested persons.

Other palaces have been entirely transformed into museums: particularly the gigantic Palace of Katherine at Tsarskoye Selo, and the Alexander Palace nearby. The entire history of the autocracy is here presented to the eyes of the workers and the young people who come to this place from Petrograd in streams ; who walk through the parks that are century-old, and then enter this palace which is kept in apple-pie order. We are successfully pursuing the aim of carefully preserving against damage, in spite of this mass attendance, not only the walls, furniture, and art works, but even the interesting mosaic floors, to preserve which we go so far, where we have not had enough protecting runners, to provide visitors with special canvas shoes to be put on over their boots. This practice inspires the visitor, no matter how little he may be accustomed to such surroundings, with the feeling that he is face to face with the property of the public, which must be guarded by both state and public with the greatest care.

In the Palace of Katherine he beholds the bizarre and heavy magnificence of the period of Elizabeth, and the graceful and pleasantly harmonious splendor of the epoch of Katherine II. This civilization of the imperial masters, who were the finest architects, decorators, and masters in porcelain, bronzes and tapestry, appears to attain its culmination during the reign of Paul, with its incomparable perfection in works of the First Empire.

The neighboring Pavlovsk is the best monument to the taste of that epoch. The excellent choice of art works constituting its equipment, as well as the admirable decoration of its salons, make Pavlovsk an incomparable structure, the like of which is hardly to be found anywhere in Europe.

But this art epoch has also left attractive traces in the Great Palace at Tsarskoye Selo. Utilizing the labor power of their serfs, the Czars, standing in proud seclusion at the head of their nobility, were able to exploit all Europe’s treasures, alternating the Asiatic luxuriousness of their Moscow ancestors with the excessive refinement of the works of European culture.

Under Alexander I, taste goes down. In his empire we find a certain coldness, which is not, however, without impressiveness. It is the reflection of the Napoleonic imperialism of Russia, with its serfdom.

And then look at the apartments of Alexander II, distinguished, commodious, with a touch of English bourgeois taste, devoid of ostentation — these are the studies and drawing rooms of a British gentleman, a wealthy country squire. And suddenly we have Alexander III before us, a curiously awkward, pseudo-Russian style, a splendor chiefly distinguished by its material wastefulness.

This decline is already noticeable under Nicholas I, with its heavy bronzes, with its second-rate Paris trinkets, products of the Second Empire.

But the coarse, quasi-Russian style of Alexander III adds an element which brings us back to Asia. Only with the utmost effort can we here discern a glimmer of true art. All of the objects are chosen for their cost, their display, their glaring and striking effects. You feel that the nobility has outlived its usefulness and is no longer the head of society, not even in the field of material civilization, not even in its house furnishings. They are already adapting themselves to the practice of living in ugly dwellings, calculated only to impress their subjects with spacious splendor and gilt and tinsel. We already feel that the autocracy is maintaining itself with difficulty, and no longer has confidence in itself; it seeks to dazzle the eye, and fails in the attempt; therefore its effort for enormous dimensions and outrageous cost of material.

If we have already witnessed a rapid drop in taste, proceeding step by step, from Alexander I to Nicholas I, from the latter to Alexander II, then to Alexander III, we behold a veritable collapse into the abyss when we gaze at the taste- less chambers of Nicholas II. What a conglomeration of things! A gaudy cotton print with photo- graphs attached, as minute as in the attic room of some millionaire’s maid. Here is a Rasputin alcove, decorated with gilt images of saints; here are curious little tubs, huge divans, and very peculiarly decorated “dressing rooms”, which arouse in us a suggestion of gross animal sensuality; you find furniture of the worst factory taste, furniture such as could be found in the rooms of suddenly enriched parvenus, who will buy any sort of “furniture” that suits their unbridled taste.

We find here a curious combination of two tendencies — the repulsive lack of taste of a degenerate Russian nobleman, and the not less repulsive lack of taste of a German philistine woman.

And yet we are speaking of the descendants of imperial dynasties! No one can free himself from the thought, even if his attention is not called to it — that the dynasty was going down, morally and esthetically, with breathless rapidity.

Our artists proposed to preserve undisturbed all the chambers of Nicholas II as models of bad taste; we have done this, for this ramble through the past, the most recent past, the period of the collapse of the Romanovs, is really a marvelous object lesson in Czarist kulturgeschichte, especially if it is aided by a preparatory lecture.

Gatchina provides much instructive material in this connection. But I fear that General Yudenich and the English bearers of culture who accompanied him have inflicted great damage upon the palaces which we so carefully protected, and which are so popular with the masses of the people, now that they have been transformed into museums.

At Moscow, the Kremlin is visited by many traveling parties. This set of buildings, with the exception of a few that are occupied by government establishments, has now become one gigantic museum of instruction, including also the churches.

The country seats surrounding Moscow are being carefully preserved by us. But, whenever their totality does not represent a unified whole, every- thing that has artistic and historical value is re- moved from them — also from the monasteries — and transported to other museums which have been added to Moscow’s attractions. The palaces which are valuable for their architecture, such as Archangelskoye and Ostankino, are even in our hard times places of pilgrimage for all those who wish to delight their eyes with unified monuments of the period which was so “glorious” for our nobility, the period when that nobility exploited and destroyed entire generations of its slaves, but was at least clever enough to live elegantly and to acquire in western Europe, in exchange for floods of Russian workers’ sweat, objects worthy of decorating such fine structures.

In a country passing through a revolutionary crisis, in which the masses are naturally inspired with hatred against the czars and masters, and involuntarily transfer this hatred even to their dwellings and furnishings, without being able to judge the artistic and historic value of these things, since these same masters and czars had permitted them to continue living in ignorance, in such a country it was of course not an easy task to carry out our work. For we had not only to dam the wave of destruction, to preserve the works of art, but it was our task to reanimate the latter, to create living beauty out of mere museum specimens, so that the worker, unconsciously thirsting for beauty, might be refreshed.

It was our task to make of inaccessible castles and palaces, where dwelt the degenerate scions of once famous families — who had become bored with everything and no longer observed anything — public institutions, which, guarded with loving care, must provide hours of pleasure for numerous visitors. This was indeed a difficult task.

The Commissariat for Public Instruction and its Section for the Protection of Historic and Art Monuments, is ready at any time to render account of its activities before civilized mankind, and, may confidently say that not only the international proletariat, which is the best part of this civilized humanity, but also every other honest man cannot withhold the tribute of respect to this immense achievement. Emphasis must be laid not only on individual cases of destruction — such might occur in any country, even in the most enlightened; but also on the fact that in a country which had been kept back in a stage of barbarism through a criminal government policy, these disturbances did not attain any great dimensions, but were transformed by the power of the government of workers and peasants into a well organized possession of the people as a whole.— The Kremlin, October 23, 1919.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v3n09-aug-28-1920-soviet-russia.pdf