Largely Spanish-speaking immigrant construction workers strike against their contractors for the most basic wages in one of the richest neighborhoods in the U.S., Westchester County, New York. The uphill battle sees interventions from the C.P.L.A., A.F.L., and C.P. only to be sold out by the craft union bureaucrats in the end. A familiar battle in U.S. labor, still played out today.

‘The Battle of White Plains’ by Benjamin Mandel from Labor Age. Vol. 20 No. 8. August, 1931.

JUST one hundred and fifty-five years after the first historic battle of White Plains, the peaceful hills of Westchester County again echoed to the roar of warfare. At that time it was a battle against the minions of King George, who sought to impose his tyrannical yoke upon the American colonists. Today it is the struggle of one thousand highway laborers for a living wage against the overlords of 1931, the highway contractors.

Westchester County, of which White Plains is the county seat, is characterized by certain distinct features. It is the wealthiest residential county in the United States, including within its confines such representatives of American plutocracy as John D. Rockefeller, Frank. A. Vanderlip, Samuel Untermeyer and many other scions of Wall Street. Certainly its total tax resources from the wealthy owners of the estates in the county, are sufficient to provide amply for a decent wage for those doing public work for the county. And yet Westchester County apparently could not afford to pay a living wage to highway laborers doing the most arduous kind of work in the boiling sun for 10, 11 and 12 hours a day.

The key to Westchester County politics, the hub around which the local business and government turns, is the mad scramble for profits on contracts for road building. Westchester County is the gateway to New York City. The question of providing adequate roads is therefore of paramount importance for the county. It seems that in recent months a number of outside contractors had submitted inordinately low bids for contract work in competition with local contractors This was popularly known as “chiseling”. They made these low bids in the expectation that they would lower labor costs through a series of drastic wage cuts bringing wages down from 75 cents to 40 cents, with the promise of further reductions to 35 and 30 cents. The contractors expected little resistance from the laborers who were completely unorganized and consisted chiefly of Spaniards, Portuguese, Italian and Negro workers, who the contractors thought could be easily terrorized and browbeaten. The expectations of the contractors were given a terrific shock by the strike of the construction laborers, which has shaken the entire county for the past two weeks.

The strike started on the job of the Peckham Road Corporation and has spread throughout White Plains to Mt. Kisco, Valhalla, Greenburgh, Chappaqua, Bedford Hills and other suburbs of White Plains, tying up millions of dollars worth of contracts. The strikers, with very few exceptions, spoke no English, and lacked the most elementary knowledge of organization and the slippery methods of the employers and their agents.

Errors Made

From the outset, before the Conference for Progressive Labor Action was called in, a number of very costly errors were made. Officers were elected in a careless manner and therefore included an insufficient number of fighting, stable elements, and Cuevez, secretary, who later sold out the strike. Meetings were conducted chiefly in Spanish, thus preventing the Negro workers, Italians and Portuguese from participating effectively. Votes were taken in a most haphazard manner, any speaker having the right to put the most important question to a snap vote by asking in Spanish for the decisive “Si?” (Yes) without pro and con discussion. Everybody was freely admitted to meetings with the right to speak and vote, whether a laborer or not, until we instituted a regular application blank for admission. Meetings were mostly agitational and inspirational and lacked effective, practical organizational character, until some time later, when we instituted a system of organizational reports and a definite picket machinery There was no real functioning executive committee, strike committee or other subcommittee Decisions were made and unmade by one or more individuals in a very loose way, oftentimes directly contrary to the expressed will of the “assembly” or general membership meeting. Members were “signed up” simply by entering their names in a book, until we established a dues system. The workers, unable to read the English press, could not follow and guide themselves by the press reactrons reported daily. They were blissfully reliant upon the righteousness of their cause, and the good-will of public officials, lawyers, etc., not realizing that might and mass power is right in a class society. This will serve to characterize the type of workers we were seeking to weld into a clearheaded, disciplined, fighting union. The strategy of the contractors from the outset was to invoke a reign of police terror to intimidate the strikers and thus break the strike. Arrests were made by the wholesale on no charges whatever. In one case an entire mass meeting was arrested. Prisoners were denied the right of counsel. The federal immigration authorities were called in and a number of the strikers have already been deported. Machine guns and tear gas bombs were introduced in order to overawe the strikers. The right of peaceful picketing was openly and flagrantly violated with the aid of police clubs, which were used ruthlessly, while police cars transported scabs to the jobs for the contractors. The wretched boarding houses of the strikers were raided at night without warrants, ostensibly in campaign for the righteous purpose of eliminating the “flop houses,” as the men’s boarding houses were called.

This campaign of frightfulness reached its highest point with the shooting of Arthur Rose, a striker, and the beating up of Alvaro Gil in the police station, both acts being committed by Police Officer McCue and later commended by Mayor McLaughlin, Chief of Police Miller and Commissioner of Safety Gennerich. The policy employed was well expressed y one police officer who declared confidentially, “If we kill a few of them, the rest will leave town.”

Terror Broken

We broke down this reign of terror in an effective manner. The American Civil Liberties Union immediately began to burn up the telegraph wires with protests to the immigration authorities. Lawyers were sent in to White Plains to defend the civil rights of the strikers, Messrs. Murray Fuerst and Samuel Cohen, displaying the utmost courage and self-sacrifice in the struggle against the high-handed methods of the White Plains police department. Charges were pressed against Officer McCue, whose cold-blooded act did much to swing public sentiment in favor of the strikers and protests were made against the beating up of Gil, the shooting of Rose and the strong-arm tactics of the Chief of Police. Finally we brought charges against the Republican Chief of Police Miller before the Democratic governor of the State, Roosevelt, demanding the former’s removal. These tactics broke the back of the terror and the contractors had to resort to another subterfuge. The time-worn bomb scare was brought into play. Only one local paper had the audacity to circulate this story with a two-inch headline reading, “Lay Explosion to Strike Bomb,” reported by Charles D. Story, vice president and William H. Peckham, president of the Peckham Road Corporation, the most vicious of the “chiselers.” Two residents not named, were said to have been thrown from their chairs by the shock, while another distinctly smelled gunpowder. The story ended as follows: “No trace of a bomb has been found and no reports of damaged machinery have been turned in to the police.” The story was hailed by the assembled strikers with gales of laughter, and was howled down with such ridicule that it never showed its head again.

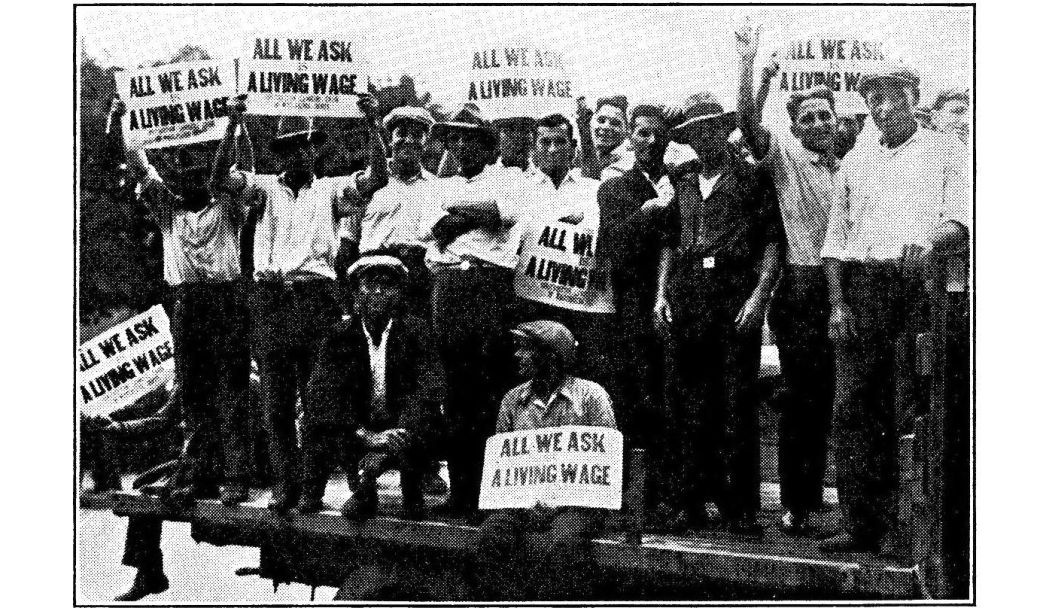

“All We Ask Is A Living Wage”

In the face of this campaign of terror, the newly-organized Construction Laborers Union of Westchester County came forward with the slogan “All We Ask Is A Living Wage,” which we carried on placards to the picket lines everywhere. We demonstrated that we were doing our best to convince the workers and the city at large, that the demand for $5.00 a day for an eight hour day was fully justified. The result of these tactics was that public sentiment was solidly with the strikers.

Picketing was carried on with the help of automobiles owned by the men, which carried the squads of pickets to each job. A legitimate criticism of the conduct of the strike is undoubtedly the fact there was insufficient mass picketing. The arrests and deportations weakened the more timid elements, who did not appear on the picket line. Scabs were brought from out-of-town by the contractors at great expense, but fortunately for the strikers, they were utterly inefficient and insufficient to carry on the work, and we depleted their number and spirit to a large extent by our picketing. Furthermore the bringing in of labor from out of town was looked upon with disfavor by the business people of the town who were dependent upon the inhabitants for patronage and trade. Contrary to the practice in other industries, on strike, highway construction, because of its nature, could not be sent elsewhere for completion, which was another advantage to the strikers. In spite of the shortcomings of the picketing, construction work was effectively crippled in and around White Plains, with more and more outside towns ready to go, as the strike progressed.

Finding ourselves considerably handicapped by the fact that we had no local counsel with an intimate knowledge of local conditions, which its vitally necessary in a strike, we received the recommendation of the name of Thomas J. O’Connor. Mr. O’Connor assured our committee that he was a fighting Irishman, whose sympathies were thoroughly with the strikers. For a time he apparently worked devotedly to help break the police terror and assist those arrested. The Conference for Progressive Labor Action representatives early saw that the correct strategy was to secure a quick settlement of the strike with such gains as could be won, and not to prolong the strike because of the very evident weaknesses of the union, the disadvantages faced by a group of foreign born workers in such a struggle, and finally because of the economic depression. The union committee instructed Mr. O’Connor to proceed with negotiations looking toward an early settlement.

O’Connor’s Moves

On Tuesday, July 21, Mr. O’Connor called the union committee to his office and presented to the committee a plan for an arbitration board, all cut and dried, which plan he had worked out without consulting the union, but on the contrary with the cooperation of Mr. Peter A. Doyle, of the State Department of Labor, and elements representing certain contractors. The arbitration board was to consist of seven members as follows: Mr. O’Connor with full power. to represent the union; Mr. Jay Downer, county engineer, who had consistently attacked the strike; a Mr. McGrath, member of the Common Council, in close touch with the contractors; one contractor; two clergymen; and Mr. Walter H. Gilpatric, president of the Chamber of Commerce. The decisions of this board were to be “final and binding.” This proposition was presented to the membership meeting of the union that night and was unanimously rejected. For his treacherous part in this attempt to sell out the strike, Mr. O’Connor’s legal connection with the union was severed and he was roundly condemned for swindling the union of $200.

But as O’Connor frequently remarked in his oily way, “There’s more than one way of killing a pig”—and also a strike. Mr. O’Connor now proceeded to negotiate individually with members of the leading committee of the union, flattering some and terrorizing others, who were out on bail under serious charges. So persistently and successfully did he work on these individuals that on the day following the mass meeting, they issued a statement in support of O’Connor and his plan. A hue and cry arose in the local press “Get Rid of Mandel.” The atmosphere was poisoned with countless rumors against the C.P.L.A. representative, and yet the strikers stood firm against O’Connor and the arbitration board.

When O’Connor’s plan was rejected we decided to propose immediate negotiations with the contractors on the basis of a committee of three representing the contractors and three representing the union. This plan the Contractors Association representing 25 leading contractors, was finally compelled to accept. The union’s demands were: $5.00 for an 8-hour day, recognition of the union, removal of scabs and employment of strikers, weekly payment of wages, time and a half for overtime. The contractors at this conference proposed the following terms: 50 cents an hour minimum. (This meant a restoration of the old rate); overtime after eight hours to be voluntary (practically a recognition of the principle of the 8-hour day); the contractors to issue a public statement containing their terms and pledging to bring pressure to bear upon any contractor who undercut the scale; tolerance of the union; removal of all scabs and the rehiring of all strikers. Anyone with the faintest knowledge of unionism and present conditions will recognize that all in all these previously unorganized foreign laborers had won a definite victory over the powerful contractors on the basis of these terms. Of course we tried to press the contractors up to 55 cents an hour, to a year’s pledge and the promise that all new contracts would be made on the basis of $5.00 for an 8-hour day. But they stood pat on the above terms, which the strikers should have accepted under protest.

Arrested

This was not done. The strikers simply could not and would not understand the necessity of a quick settlement on the basis of certain gains with the opportunity of consolidating and enlarging their union. They refused to grasp the necessary understanding of the various objective forces at work and, while sluggish in doing picket duty, obstinately adhered to the demand for $5.00 a day for an 8-hour day, disregarding the practical consideration that the largest contractors had signed estimates, which would make them fight with the most: desperate methods against terms which they considered impossible to meet. Early in the strike, the strikers had turned down an offer of $5.00 for a 8-hour day, which was also a mistake. Meanwhile the police department sent out a special automobile squad on Saturday morning, obviously with the purpose of “getting Mandel,” and they did. I was arrested on the preposterous charge of pushing a 250pound armed officer and held in jail until after the afternoon meeting. At this meeting, under the direction of Cuevez, who was O’Connor’s tool, the strikers decided to accept the arbitration proposal and thus leave themselves entirely in O’Connor’s hands. I was later ruled out of the strike to the joy of the local press. The outcome of this move is obvious. The decision of the arbitration board will undoubtedly be the complete withdrawal of even those meager concessions which the men had already won. It is necessary to comment briefly on the role of the A.F. of L. and of the Communists. In spite of the fact that the highway laborers were in the front lines of struggle to defend the wage scales of the entire county, the A.F. of L. of Westchester County gave not a particle of practical support, and limited itself to vague generalities and promises, conditional upon affiliation with Yonkers Local 60, which is under the most corrupt and incompetent leadership. The strikers demanded an autonomous local, which was refused. Efforts may be made to bribe the local leadership with certain offers in order to get them to join the A.F. of L., finally.

The Communists several times and in various ways tried to inject themselves into the strike. Our policy was to inject no extraneous issues, to make it a clear fight for a living wage. The contractors tried repeatedly and unsuccessfully to inject the Communist issue, but they were unsuccessful until the Trade Union Unity League issued a public statement denouncing me as a “renegade Communist.” This was luridly played up by the press, the day before my arrest. They also tried to capture a meeting by the new storm tactics of rushing the chair, but were thrown out for their pains. In spite of these methods and a number of scurrilous leaflets issued in English and Spanish, the Communists secured no foothold in the strike, but played a definite part in disorganizing the poorly organized forces of the laborers and in presenting the contractors with a Communist bogie.

What will be the outcome of it all? There is every hope and indication that as a result of the struggle, and the inspiring messages of C.P.L.A. through A.J. Muste, Rose Pesotta, Jack Lever, and Louis F. Budenz, the seed of organization has penetrated and taken root. It will not be long before the men under the attacks of the contractors, will again be compelled to seriously tackle the question of organization. The present struggle has succeeded in knitting together a more clear, conscious and practical kernel, who, let us hope, will be the center and the driving force of a real organization and the future battle of White Plains.

Note: Since this article was written, the men have been signed up into Local 60, Common Laborers Union, A.F. of L. by Mr. Thomas J. O’Connor and Esquiel Cuevas, who have entered into an agreement to work “as far as possible.” At least 75 per cent of the strikers have been refused reemployment, and the scabs are being retained. In other words the laborers have been led into a most shameful sell-out.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v20n08-Aug-1931-Labor%20Age.pdf