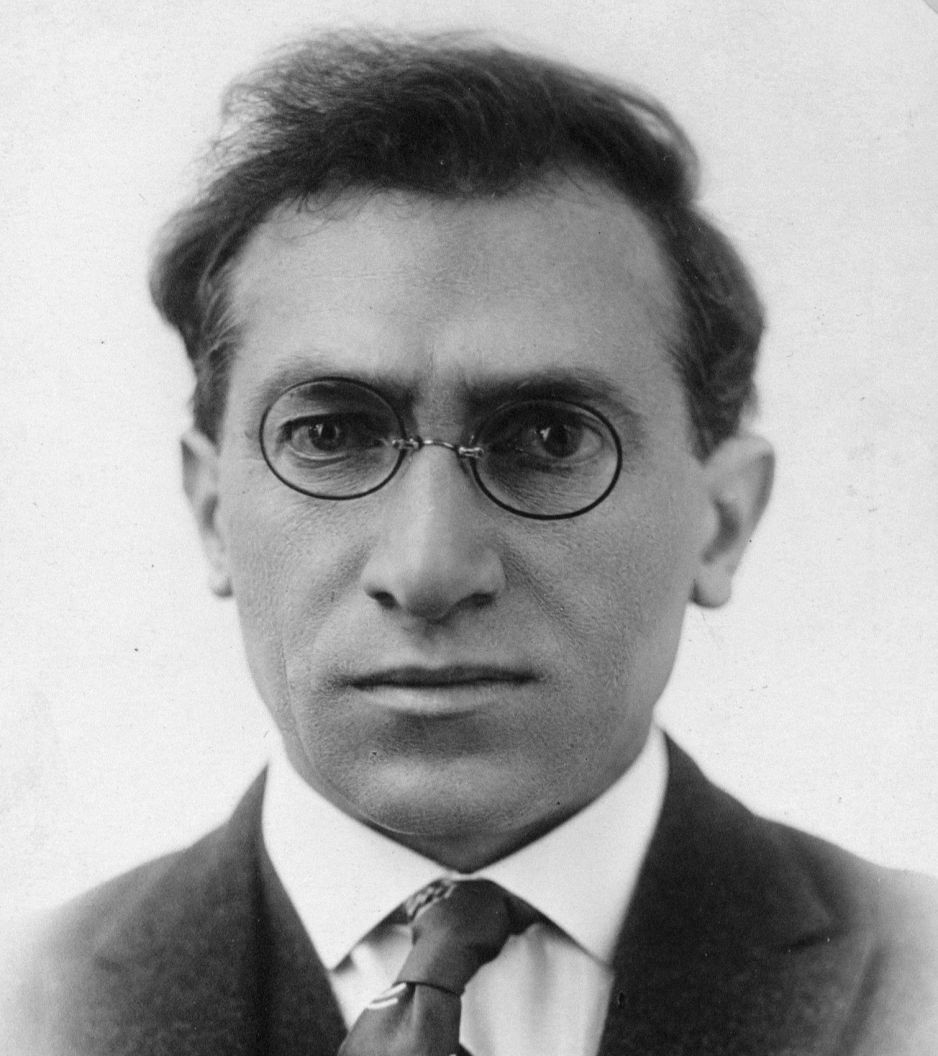

At his best, Olgin was, even in translation from the original Yiddish, an extraordinary writer. That work includes his series written for Forward during and after his six-month tour of Soviet Russia at the end of the Civil War. Olgin, who was a leading voice of the Bund during the 1905 Revolution, came to the Bolsheviks critically. In the U.S. he remained a member of the Socialist Party as a leader of the Workers Council group which sought to ally with the Third International. He would join the Communist movement with the creation of the Workers Party in December, 1921 and became editor of the Morgen Freiheit, which he continued for the rest of his life.

‘The Intellectual in the Russia of Today’ by Moissaye Olgin from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 4 No. 19. May 7, 1921.

(The following, one of a series of brilliant articles on Soviet Russia from the pen of a writer who recently visited Russia, appearing in the Jewish daily, “Forward,” of New York, is taken from the April 9 issue of that newspaper.)

RUSSIA has been passing through a fine school of experience. She has waged war for seven and a half years–first against foreign enemies and then on battlefronts both within and without of the country. The revolutionary cauldron has been boiling for four consecutive years. She has endured hunger and uprisings, experienced defeats and victories and always blood, blood, blood. What has become of the people, then?

I know that this is not an easy question to answer. People are not alike. Their souls are hidden. Once there was literature, and literature painted souls. Today there is practically no literature. The little there is does not paint a picture. And people’s moods change rapidly. And one is not today what he was yesterday.

What to do, then? I shall write down my impressions. I have seen many people, and conversed with many as with friends. I think I have obtained a general view. I may be mistaken, but I believe not.

First the intellectual. The intellectual has lost his glory. It is terrible to see how people can fall suddenly from their height. What was it that was beautiful in the Russian intellectual? First, the play of feeling, second, the revolutionary tendency, third, intellectual creation, fourth, the seeking for an answer to the riddles of life. Alas, what has become of all this beauty! The intellectual now wears a peasants’ coat, thick felt boots, a soldier’s cap, and it seems that together with his fine clothes he has lost his finest feelings. And again: can one dream of love when one has an empty stomach? Can one admire Nature when fear is gnawing at one’s heart? Can one weave a web of the finest dreams and desires when the only thing that matters is the question of rations? The intellectual no longer possesses that vari-colored gamut of rich and tender and deep and soft and gentle human feelings that speak to us in Chekhov’s ales, in Bunin’s dreamy idylls, in Sologub’s lyrics, in Zaitsev’s sketches, Poor has become the intellectual. Gray has become the intellectual.

You will say: like time, like feelings. A harp is out of place in the noise of a storm. One does not play the cello to the march of soldiers. But hear sounds a trumpet in the music of the storm, and amidst the alarms of war new strong impetuous feelings can bloom. There was peace, and then came a volcanic upheaval. There were feelings in half-tones, now there must be hardened souls. Thus you will speak–and you will be right. But unfortunately the intellectual has turned away from the new. He has not recognized the revolution. He has cursed its ways and its hopes. He has turned his back upon the course of history, and only hunger has driven him to fit himself into the present order. But in his heart he is hostile to it. In his heart he is a stranger. It is not even hate. Hate is strong. Hate has color. The intellectual can only complain and grumble to himself. His heart is full of petty complaints. He sulks. Not for him the bright red fires.

What is there left for him? Creative work in the sphere of science? Here also the new is in the way. Scores of professors, hundreds of writers, have worked for years in history, sociology, political economy–and their theories have shown absolutely that what is now taking place in Russia is impossible. And yet it is taking place. It is glaringly apparently. Still more: it commands, it rules. To continue scientific work is difficult. To change one’s theories is still more difficult. One hangs as between heaven and earth. The sphere of natural science remains neutral, but the poverty of the country prevents the doing of scientific work.

And as for seeking an answer to the riddles of life, this has now lost all meaning. It is all right at a time when life has a form and a fixed direction. Now life changes its face every day. What is the use of touching its surface with the soft pen of philosophic commentary, when here they are digging at it with spades, and the sound is heard of hammers and axes?

The intellectual is bankrupt. He is one fallen from high estates. His soul is a waste place, covered with dust and dirt. What does the intellectual want? What are his visions? If he were honest with himself he would confess that he wants to go back. If you converse with him he will tell you that he is not a reactionary. But what is progressive and what is reactionary is not now clear to him. He has no program. He can show you no course of action.

When you look at the intellectuals, they all seem to be going about with bowed heads. In the morning they drag themselves to the schools, universities, hospitals, government offices, military institutions. At four o’clock they return home. They eat their good dinner of soup and gruel, they read the Soviet newspaper, they perform their household chores: chop wood, bring up water from the yard, take down the dirty water in buckets (water pipes and sewers are not working), procure their rations, perhaps buy something illegally. Meanwhile it is getting late. The electric light glimmers faintly. It is cold in the house. One’s heart is sad. One does not read, one does not dream, one does not love, as once upon a time.

The intellectual sits and recalls the days of his glory. His dissatisfaction increases. His position appears to him worse than it is. He thinks that “they”, the present rulers, are responsible for everything. He forgets the war and the blockade and all the misfortunes. He must have a scapegoat He must have somebody to grumble at. The favorite theme now among the Russian intellectuals is the dishonesty of the commissars. Just as if things would be very different if the commissars were all angels.

Deep in his heart the intellectual feels another pain. He has been robbed of his primogeniture, he has been deprived of his leadership. For scores of years he believed that history had singled him out to be the leader of the masses. And the masses came and pushed him aside. He is ordered about by a person who has studied little and brooded little, who commands rudely, without refinement. The son of the masses says to the intellectual, openly, to his face: “You, brother, teach me what you know, and I will be able to get rid of you forever. I need your knowledge, in order to build up my life, but you yourself I do not need at all.” The intellectual broods about this. It hurts like a wound.

A mood of depression prevails at all the intellectual meetings, discussions, lectures. Consider the students, for example. Youth is carefree. Youth can endure physical discomfort more easily. One would think that the students now are living people. Were not the students in Russia always very active? They played a leading progressive and revolutionary role among the Russian intellectuals. Observe the students now—they are old men of twenty years, without a divine spark, without a dream which warms the soul. They are so practical. Such calculating petty bourgeois. There is no difference between the father of the intellectual and the son. Remarkable! The students do not even want to know about politics. They do not want even to hear of the great problems their country is facing. Better students have complained in my presence that in the matter of political ideas the great mass of the students are far inferior to the average worker. What do they do? They study because they must take examinations. They study because they must become “specialists.” And of course there is no soul in this study.

Surely they, the students, ought not to complain. Most of the students receive rations and quarters from the state—and all that is required of them is to study. It is true that the rations will not make you fat, you must yourself heat and clean your own rooms. But all Russia lives thus—everyone is glad to have food and lodging. And when have the Russian students lived like counts? Formerly, 85 per cent of the Russian students had nothing to live on, and were supremely happy to give lessons or do clerical work for 15 rubles a month. It is interesting that previously they did not complain about anybody, and now they complain constantly.

This is one of the most remarkable psychological phenomena in the Russia of today. If tomorrow a Denikin or some other devil entered Moscow and introduced a bourgeois order of things, this tame student would lose his ration and run about breathless, looking for a small job to do, but he would not blame anybody for his poverty. That is just his luck, he would think. But if the day after tomorrow the soviet regime should return, together with his ration, he would again begin to grumble. This was seen at Minsk, where the power passed over from the Soviets to the Poles, and then again to the Soviets. This was seen at Kiev and Kharkov, where the power changed hands frequently. It merely shows that the population demands more of the Soviet regime than of another regime.—Even the intelligentsia, who do not want to lend the Soviet regime a hand at a most critical time, demand more.

The intellectual masses in general create the impression that they are people of yesterday. They all do something—the physicians treat the sick, the engineers work at the factories, the jurists busy themselves with new laws, teachers instruct their pupils, writers look for somebody to print their things: they hold meetings, give public lectures, make protests,—but everything is anemic and of yesterday. Yesterday’s books, yesterday’s thoughts, yesterday’s problems, yesterday’s ideals. Today is a step-child.

What is the Russian intellectual? Life’s outcast He is not sure of the ground under his feet He is not sure of himself. It is needless to say that he is not beautiful. People of yesterday are never beautiful.

There is something lowly about perpetual complaint If you are dissatisfied, fight, die, if you must! Otherwise, clench your teeth and keep still. That is dignified. To sit and gossip and dig up all your enemy’s petty sins, and then come to that same enemy and serve him as a “specialist”, and do the work like an unfaithful servant—that is unworthy. The Russian intelligentsia are no longer made in God’s image.

And when their enemies come and reproach them with the words “petty bourgeois”, and say that they have lost their sense of life, that they have not felt the pulse of history, that they hinder the development of the new—one cannot blame them. These enemies are also so-called intellectuals, a mere handful of intellectuals who have allied themselves with the new and helped to create the new. They are altogether different types.

Of them we shall speak later.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: (large file): https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v4-5-soviet-russia%20Jan-Dec%201921.pdf