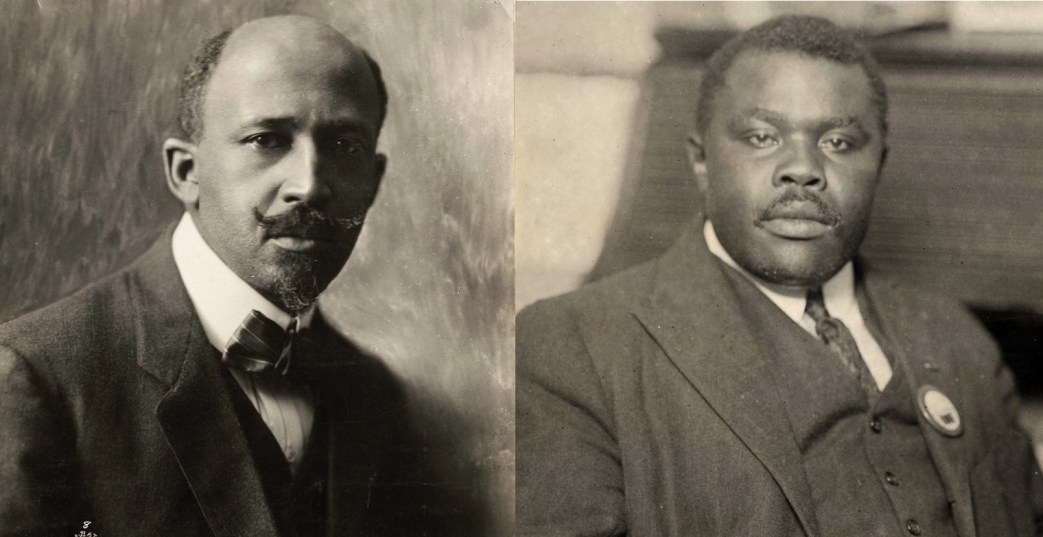

Du Bois’ estimation of Marcus Garvey in two parts from The Crisis.

‘Marcus Garvey’ by W.E.B. Du Bois from The Crisis. Vol. 21 Nos. 2 & 3. December, 1920 & January, 1921.

MARCUS GARVEY was born at St. Ann’s Bay, Jamaica, about 1885. He was educated at the public school and then for a short time attended the Church of England Grammar School, although he was a Roman Catholic by religion. On leaving school he learned the printing trade and followed it for many years. In Costa Rica he was associated with Marclam Taylor in publishing the Bluefield’s Messenger. Later he was on the staff of La Nacion. He then returned to Jamaica and worked as a print er, being foreman of the printing department of P. Benjamin’s Manufacturing Company of Kingston. Later he visited Europe and spent some time in England and France and while abroad conceived his scheme of organizing the Negro Improvement Society. This society was launched August 1, 1914, in Jamaica, with these general objects among others:

“To establish a Universal Confraternity among the race”; “to promote the spirit of race pride and love”; “to administer to and assist the needy”; “to strengthen the imperialism of independent African States”; “to conduct a world-wide commercial and industrial intercourse”.

His first practical object was to be the establishment of a farm school. Meetings were held and the Roman Catholic Bishop, the Mayor of Kingston, and many others addressed them. Nevertheless the project did not succeed and Mr. Garvey was soon in financial difficulties. He therefore practically abandoned the Jamaica field and came to the United States. In the United States his movement for many years languished until at last with the increased migration from the West Indies during the war he succeeded in establishing a strong nucleus in the Harlem district of New York City.

His program now enlarged and changed somewhat in emphasis. He began especially to emphasize the commercial development of the Negroes and as an islander familiar with the necessities of ship traffic he planned the “Black Star Line”. The public for a long time regarded this as simply a scheme of exploitation, when they were startled by hearing that Garvey had bought a ship. This boat was a former coasting vessel, 32 years old, but it was put into commission with a black crew and a black captain and was announced as the first of a fleet of vessels which would trade between the colored peoples of America, the West Indies and Africa. With this beginning, the popularity and reputation of Mr. Garvey and his association increased quickly.

In addition to the Yarmouth he is said to have purchased two small boats, the Shadyside, a small excursion steamer which made daily excursions up the Hudson, and a yacht which was designed to cruise among the West Indies and collect cargo in some central spot for the Yarmouth. He had first announced the Black Star Line as a Five Million Dollar corporation, but in February, 1920, he announced that it was going to be a Ten Million Dollar corporation with shares selling at Five Dollars. To this he added in a few months the Negro Factories Corporation capitalized at One Million Dollars with two hundred thousand one dollar shares, and finally he announced the subscription of Five Million Dollars to free Liberia and Haiti from debt.

Early in 1920 he called a convention of Negroes to meet in New York City from the 1st to the 31st of August, “to outline a constructive plan and program for the uplifting of the Negroes and the redemption of Africa”. He also took title to three apartment houses to be used as offices and purchased the foundation of an unfinished Baptist church which he covered over and used for meetings, calling it “Liberty Hall”. In August, 1920, his convention met with representatives from various parts of the United States, several of the West India Islands and the Canal Zone and a few from Africa. The convention carried out its plan of a month’s meetings and culminated with a mass meeting which filled Madison Square Garden. Finally the convention adopted a “Declaration of Independence” with 66 articles, a universal anthem and colors, red, black and green–and elected Mr. Garvey as “His Excellency, the Provisional President of Africa”, together with a number of various other leaders from the various parts of the Negro world. This in brief is the history of the Garvey movement.

The question comes (1) Is it an honest, sincere movement? (2) Are its industrial and commercial projects business like and effective? (3) Are its general objects plausible and capable of being carried out?

The central and dynamic force of the movement is Garvey. He has with singular success capitalized and made vocal the great and long suffering grievances and spirit of protest among the West Indian peasantry. Hitherto the black peasantry of the West Indies has been almost leaderless. Its natural leaders, both mulatto and black, have crossed the color line and practically obliterated social distinction, and to some extent economic distinction, between them and the white English world on the Islands. This has left a peasantry with only the rudiments of education and with almost no economic chances, grovelling at the bottom. Their distress and needs gave Garvey his vision.

It is a little difficult to characterize the man Garvey. He has been charged with dishonesty and graft, but he seems to me essentially an honest and sincere man with a tremendous vision, great dynamic force, stubborn determination and unselfish desire to serve; but also he has very serious defects of temperament and training: he is dictatorial, domineering, ordinately vain and very suspicious. He cannot get on with his fellow-workers. His entourage has continually changed.1 He has had endless law suits and some cases of fisticuffs with his subordinates and has even divorced the young wife whom he married with great fanfare of trumpets about a year ago. All these things militate against him and his reputation. Nevertheless I have not found the slightest proof that his objects were not sincere or that he was consciously diverting money to his own uses. The great difficulty with him is that he has absolutely no business sense, no flair for real organization and his general objects are so shot through with bombast and exaggeration that it is difficult to pin them down for careful examination.

On the other hand, Garvey is an extraordinary leader of men. Thousands of people believe in him. He is able to stir them with singular eloquence and the general run of his thought is of a high plane. He has become to thousands of people a sort of religion. He allows and encourages all sorts of personal adulation, even printing in his paper the addresses of some of the delegates who hailed him as “His Majesty”. He dons on state occasion, a costume consisting of an academic cap and gown flounced in red and green!

Of Garvey’s curious credulity and suspicions one example will suffice: In March, 1919, he held a large mass meeting at Palace Casino which was presided over by Chandler Owen and addressed by himself and Phillip Randolph. Here he collected $204 in contributions on the plea that while in France, W.E.B. DuBois had interfered with the work of his “High Commissioner” by “defeating” his articles in the French press and “repudiating” his statements as to lynching and injustice in America! The truth was that Mr. DuBois never saw or heard of his “High Commissioner”, never denied his nor anyone’s statements of the wretched American conditions, did everything possible to arouse rather than quiet the French press and would have been delighted to welcome and co-operate with any colored fellow-worker.

II.

WHEN it comes to Mr. Garvey’s industrial and commercial enterprises there is more ground for doubt and misgiving than in the matter of his character. First of all, his enterprises are incorporated in Delaware, where the corporation laws are loose and where no financial statements are required.2 So far as I can find, and I have searched with care, Mr. Garvey has never published a complete statement of the income and expenditures of the Negro Improvement Association or of the Black Star Line or of any of his enterprises, which really revealed his financial situation. A courteous letter of inquiry sent to him July 22, 1920, asking for such financial data as he was willing for the public to know, remains to this day unacknowledged and unanswered.

Now a refusal to publish a financial statement is no proof of dishonesty, but it is proof that either Garvey is ill-advised and unnecessarily courting suspicion, or that his industrial enterprises are not on a sound business basis; otherwise he is too good an advertiser not to use a promising balance-sheet for all it is worth.

There has been one balance sheet, published July 26, 1920, purporting to give the financial condition of the Black Star Line after one year of operation; neither profit or loss is shown, there is no way to tell the actual cash receipts or the true condition of the business. Nevertheless it does make some interesting revelations.

The total amount of stock subscribed for is $590,860. Of this $118,153.28 is not yet paid for, leaving the actual amount of paid-in capital charged against the corporation, $472,706.72. Against this stands only $355,214.59 of assets (viz.: $21,985.21 in cash deposits and loans receivable; $12,975.01 in furniture and equipment, $288,515.37 which is the alleged value of his boats, $26,000 in real estate and $5,739 of insurance paid in advance). To offset the assets he has $152,264.14 of other liabilities (accrued salaries, $1,539.30; notes and accounts payable, $129,224.84; mortgages due $21,500). In other words, his capital stock of $472,706.72 is after a year’s business impaired to such extent that he has only $202,950.45 to show for it.

Even this does not reveal the precariousness of his actual business condition. Banks before the war in lending their credit refused to recognize any business as safe unless for every dollar of current liabilities there were two dollars of current assets. Today, since the war, they require three dollars of current assets to every one of current liabilities. The Black Star Line had July 26, $16,485.21 in current assets and $130,764.14 in current liabilities, when recognition by any reputable bank called for $390,000 in current assets.

Moreover, another sinister admission appears in this statement: the cost of floating the Black Star Line to date has been $289,066.27. In other words, it has cost nearly $300,000 to collect a capital of less than half a million. Garvey has, in other words, spent more for advertisement than he has for his boats!

This is a serious situation, and even this does not tell the whole story: the real estate, furniture, etc., listed above, are probably valued correctly. But how about the boats? The Yarmouth is a wooden steamer of 1,452 gross tons, built in 1887. It is old and unseaworthy; it came near sinking a year ago and it has cost a great deal for repairs. It is said that it is now laid up for repairs with a large bill due. Without doubt the inexperienced purchasers of this vessel paid far more than it is worth, and it will soon be utterly worthless unless rebuilt at a very high cost.3

The cases of the Kanawha (or Antonio Maceo) and the Shadyside are puzzling. Neither of these boats is registered as belonging to the Black Star Line at all. The former is recorded as belonging to C.L. Dimon, and the latter to the North and East River Steamboat Company. Does the Black Star Line really own these boats, or is it buying them by installments, or only leasing them? We do not know the facts and have been unable to find out. Under the circumstances they look like dubious “assets”.

The majority of the Black Star stock is apparently owned by the Universal Negro Improvement Association. There is no reason why this association, if it will and can, should not continue to pour money into its corporation. Let us therefore consider then Mr. Garvey’s other resources.

Mr. Garvey’s income consists of (a) dues from members of the U.N.I. Association; (b) shares in the Black Star Line and other enterprises, and (e) gifts and “loans” for specific objects. If the U.N.I. Association has “3,000,000 members” then the income from that source alone would be certainly over a million dollars a year. If, as is more likely, it has under 300,000 paying members, he may collect $150,000 annually from this source. Stock in the Black Star Line is still being sold. Garvey himself tells of one woman who had saved about four hundred dollars in gold: “She brought out all the gold and bought shares in the Black Star Line.” Another man writes this touching letter from the Canal Zone: “I have sent twice to buy shares amounting to $125, (numbers of certificates. 3752 and 9617). Now I am sending $35 for seven more shares. You might think I have money, but the truth, as I stated before, is that I have no money now. But if I’m to die of hunger it will be all right because I’m determined to do all that’s in my power to better the conditions of my race.”4

In addition to this he has asked for special contributions. In the spring of 1920 he demanded for his coming convention in August, “a fund of two million dollars ($2,000,000) to capitalize this, the greatest of all conventions.” In October he acknowledged a total of something over $16.000 in small contributions. Immediately he announced “a constructive loan” of $2,000,000, which he is presumably still seeking to raise.5

From these sources of income Mr. Garvey has financed his enterprises and carried on a wide and determined propaganda, maintained a large staff of salaried officials, clerks and agents, and published a weekly newspaper. Notwithstanding this considerable income, there is no doubt that Garvey’s expenditures are pressing hard on his income, and that his financial methods are so essentially unsound that unless he speedily revises them, the investors will certainly get no dividends and worse may happen.6 He is apparently using the familiar method of “Kiting” i.e., the money which comes in as investment in stock is being used in current expenses, especially in heavy overhead costs, for clerk hire, interest and display. Even his boats are being used for advertisement more than for business–lying in harbors as exhibits, taking excursion parties, etc. These methods have necessitated mortgages on property and continually new and more grandiose schemes to collect larger and larger amounts of ready cash. Meantime, lacking business men of experience, his actual business ventures have brought in few returns, involved heavy expense and threatened him continually with disaster or legal complication.

On the other hand, full credit must be given Garvey for a bold effort and some success. He has at least put vessels manned and owned by black men on the seas and they have carried passengers and cargoes. The difficulty is that he does not know the shipping business, he does not understand the investment of capital, and he has few trained and staunch assistants.

The present financial plight of an inexperienced and headstrong promoter may therefore decide the fate of the whole movement. This would be a calamity. Garvey is the beloved leader of tens of thousands of poor and bewildered people who have been cheated all their lives. His failure would mean a blow to their faith, and a loss of their little savings, which it would take generations to undo.

Moreover, shorn of its bombast and exaggeration, the main lines of the Garvey plan are perfectly feasible. What he is trying to say and do is this: American Negroes can, by accumulating and ministering their own capital, organize industry, join the black centers of the south Atlantic by commercial enterprise and in this way ultimately redeem Africa as a fit and free home for black men. This is true. It is feasible. It is, in a sense, practical; but it will take for its accomplishment long years of painstaking, self-sacrificing effort. It will call for every ounce of ability, knowledge, experience and devotion in the whole Negro race. It is not a task for one man or one organization, but for co-ordinate effort on the part of millions. The plan is not original with Garvey but he has popularized it, made it a living, vocal ideal and swept thousands with him with intense belief in the possible accomplishment of the ideal.

This is a great, human service; but when Garvey forges ahead and almost single-handed attempts to realize his dream in a few years, with large words and wild gestures, he grievously minimizes his task and endangers his cause.

To instance one illustrative fact: there is no doubt but what Garvey has sought to import to America and capitalize the antagonism between blacks and mulattoes in the West Indies. This has been the cause of the West Indian failures to gain headway against the whites. Yet Garvey imports it into a land where it has never had any substantial footing and where today, of all days, it is absolutely repudiated by every thinking Negro; Garvey capitalizes it, has sought to get the cooperation of men like R.R. Moton on this basis, and has aroused more bitter color enmity inside the race than has ever before existed. The whites are delighted at the prospect of a division of our solidifying phalanx, but their hopes are vain. American Negroes recognize no color line in or out of the race, and they will in the end punish the man who attempts to establish it.

Then too Garvey increases his difficulties in other directions. He is a British subject. He wants to trade in British territory. Why then does he needlessly antagonize and even insult Britain? He wants to unite all Negroes. Why then does he sneer at the work of the powerful group of his race in the United States where he finds asylum and sympathy? Particularly, why does he decry the excellent and rising business enterprises of Harlem–intimating that his schemes alone are honest and sound when the facts flatly contradict him? He proposes to settle his headquarters in Liberia but has he asked permission of the Liberian government? Does he presume to usurp authority in a land which has successfully withstood England, France and the United States, but is expected tamely to submit to Marcus Garvey? How long does Mr. Garvey think that President King would permit his anti-English propaganda on Liberian soil, when the government is straining every nerve to escape the Lion’s Paw?

And, finally, without arms, money, effective organization or base of operations, Mr. Garvey openly and wildly talks of “Conquest” and of telling white Europeans in Africa to “get out!” and of becoming himself a black Napoleon!7

Suppose Mr. Garvey should drop from the clouds and concentrate on his industrial schemes as a practical first step toward his dreams: the first duty of a great commercial enterprise is to carry on effective commerce. A man who sees in industry the key to a situation, must establish sufficient business-like industries. Here Mr. Garvey has failed lamentably.

The Yarmouth, for instance, has not been a commercial success. Stories have been published alleging its dirty condition and the inexcusable conduct of its captain and crew. To this Mr. Garvey may reply that it was no easy matter to get efficient persons to run his boats and to keep a schedule. This is certainly true, but if it is difficult to secure one black boat crew, how much more difficult is it going to be to “build and operate factories in the big industrial centers of the United States, Central America, the West Indies and Africa to manufacture every marketable commodity”? and also “to purchase and build ships of larger tonnage for the African and South American trade”? and also to raise “Five Million Dollars to free Liberia” where “new buildings are to be erected, administrative buildings are to be built, colleges and universities are to be constructed”? and finally to accomplish what Mr. Garvey calls the “Conquest of Africa”!

To sum up: Garvey is a sincere, hard-working idealist; he is also a stubborn, domineering leader of the mass; he has worthy industrial and commercial schemes but he is an inexperienced business man. His dreams of Negro industry, commerce and the ultimate freedom of Africa are feasible; but his methods are bombastic, wasteful, illogical and ineffective and almost illegal. If he learns by experience, attracts strong and capable friends and helpers instead of making needless enemies; if he gives up secrecy and suspicion and substitutes open and frank reports as to his income and expenses, and above all if he is willing to be a co-worker and not a czar, he may yet in time succeed in at least starting some of his schemes toward accomplishment. But unless he does these things and does them quickly he cannot escape failure.

Let the followers of Mr. Garvey insist that he get down to bed-rock business and make income and expense balance; let them gag Garvey’s wilder words, and still preserve his wide power and influence. American Negro leaders are not jealous of Garvey–they are not envious of his success; they are simply afraid of his failure, for his failure would be theirs. He can have all the power and money that he can efficiently and honestly use, and if in addition he wants to prance down Broadway in a green shirt, let him–but do not let him foolishly overwhelm with bankruptcy and disaster one of the most interesting spiritual movements of the modern Negro world.

NOTES

1. Of the 15 names of his fellow officers in 1914 not a single one appears in 1918; of the 18 names of officers published in 1918 only 6 survive in 1919; among the small list of principal officers published in 1920 I do not find a single name mentioned in 1919.

2. Mr. Garvey boasts Feb. 14, 1920: “This week I present you with the Black Star Line Steamship Corporation recapitalized at ten million dollars. They told us when we incorporated this corporation that we could not make it, but we are now gone from a $5,000,000 corporation to one of $10,000,000.”

3. This sounds impressive, but means almost nothing. The fee for incorporating a $5,000,000 concern in Delaware is $350. By paying $250 more the corporation may incorporate with $10,000,000 authorized capital without having a cent of capital actually paid in! Cf. “General Corporation Laws of the State of Delaware”, edition of 1917.

3. Technically the Yarmouth does not belong to the Black Star Line of Delaware, but to the “Black Star Line of Canada, Limited,” incorporated in Canada, March 23, 1920, with one million dollars capital. This capital consists of $500 cash and $999,500 “assets.” Probably the Black Star Line of Delaware controls this corporation, but this is not known.

4. P.N. Gordon.

5. “The Universal Negro Improvement Association is raising a constructive loan of two million dollars from its members. Three hundred thousand dollars out of this two million has been allotted to the New York Local as its quota, and already the members in New York have started to subscribe to the loan, and in the next seven days the three hundred thousand dollars will be oversubscribed. The great divisions of Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Wilmington, Baltimore and Washington will also over-subscribe their quota to make up the two million dollars.

“Constructive work will be started in January, 1921, when the first ship of the Black Star Line on the African trade will sail from New York with materials and workmen for this constructive work.”

Eleven days later, November 6th, the Negro World is still “raising the loan” but there is no report of the amount raised.

6. It might be argued that it is not absolutely necessary that the Black Star Line, etc., should pay financially. It is quite conceivable that Garvey should launch a business philanthropy, and that without expectation of return, colored people should contribute for a series of years to support Negro enterprise. But this is not Garvey’s idea. He says plainly in a circular:

“The Black Star Line corporation presents to every Black Man, Woman and Child the opportunity to climb the great ladder of industrial and commercial progress. If you have ten dollars, one hundred dollars, or one or five thousand dollars to invest for profit, then take out shares in The Black Star Line, Inc. This corporation is chartered to trade on every sea and all waters. The Black Star Line will turn over large profits and dividends to stockholders, and operate to their interest even whilst they will be asleep.”

7. He said in his “inaugural” address:

“The signal honor of being Provisional President of Africa is mine. It is a political job; it is a political calling for me to redeem Africa. It is like asking Napoleon to take the world. He took a certain portion of the world in his time. He failed and died at St. Helena. But may I not say that the lessons of Napoleon are but stepping stones by which we shall guide ourselves to African liberation?”

The Crisis A Record of the Darker Races was founded by W. E. B. Du Bois in 1910 as the magazine of the newly formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. By the end of the decade circulation had reached 100,000. The Crisis’s hosted writers such as William Stanley Braithwaite, Charles Chesnutt, Countee Cullen, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Angelina W. Grimke, Langston Hughes, Georgia Douglas Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, Alain Locke, Arthur Schomburg, Jean Toomer, and Walter White.

PDF of issue 1: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/workers/civil-rights/crisis/1200-crisis-v21n02-w122.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/workers/civil-rights/crisis/0100-crisis-v21n03-w123.pdf