An extremely valuable primer on the myriad of mid-1920s political parties in Weimar Germany from Peter Maslovski. Political turmoil after the crisis in late 1923 would result in two federal parliamentary elections in a year. Called by the minority coalition led by the Centre Party’s Wilhelm Marx who’s support of the Dawe’s Plan lost it support from the right, in the May, 1924 elections the Communists had just emerged from illegality with the former leadership around Brandler removed in the aftermath of the failed ‘German October’ and the left under Ruth Fischer and Arkadi Maslow assuming leadership. In the May the C.P. received 12.5%, or 3.7 million votes, while the Social Democrat were the largest party at 22%, 6 million votes. In the December elections, the C.P. vote fell to 9% (2.7 million) while the Social Democrats continued to be the largest party, 26% (7.9 million). However, the Centre party with a new unsteady coalition including liberals and the far right under ‘technocrat’ Hans Luther were able to retain power.

‘Rallying for the German Election Campaign’ by Peter Maslovski from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 4 No. 25. April 17, 1924.

Over two dozen Parties.

Already up to April 1st no less than twenty-five parties an unheard of number for German conditions have entered with lists of candidates for the elections to the German Reichstag and one still hears of new parties, groups, and even small groups who are announcing candidates. With this, Germany has reached a record as regards the number of competing parties.

I.

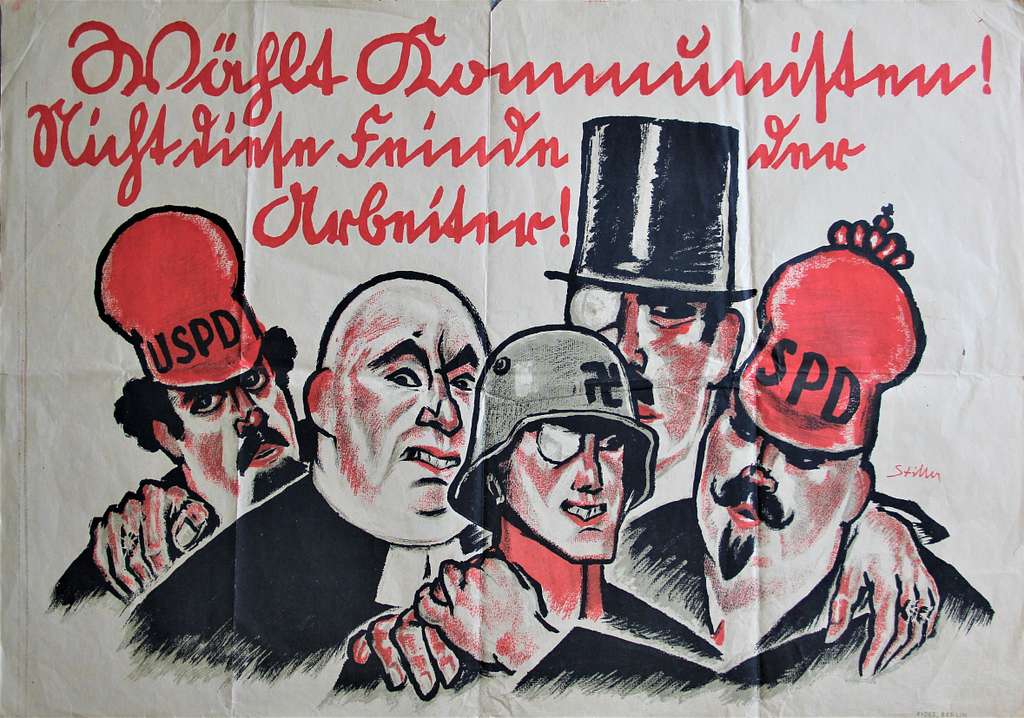

The basic plan of the party formations is to be found in the chief parties of the Reichstag, from which individual oppositional groups have broken off from time to time and set themselves up as independent parties. These chief parties are 1. The German Nationalist (Deutschnational) which is monarchist and is based first of all upon the agrarian capital of the junkers, but is also supported by the middle classes, officers, officials, artizans and small shopkeepers who allege that they have been reduced to misery by the Republic. 2. The German People’s Party (Deutsche Volkspartei), the party of Stinnes, of the industrial capitalists, who for the sake of profits can also place themselves upon the “hard facts” of the republic. 3. The Centre (Zentrum), a party which is less easy to define, because alongside of the Christian trade unions, officials, workers, upper and lower clergy, are to be found the great industrialists of the type of Peter Klöckner, large landowners of the type of the Westphalian counts and stock exchange jobbers like Louis Hagen, the baptised jew from Cologne. 4. The Democratic Party, which finds it financial support in the ranks of finance and stock exchange capital, but is at the same time a party of those classes, mostly intellectuals, who after the revolution discovered that they were republicans. 5. The Social Democratic Party, which is without doubt the most conservative party in Germany today, as its whole wisdom has exhausted itself in the demand for the maintenance of the purely outward form of the republic both against right and left. 6. The Communist Party, which is the only purely proletarian and revolutionary party. In this connection, the smaller groups of the old Reichstag, such as the Bavarian People’s Party, the Hanoverians, the two Independent etc. need not be considered.

II.

The German Nationalists have had to yield up their most active elements to the various kinds of fatherland, national, and Pan-German organizations, which seemed to promise more speedy success to the reactionary mass by their fascist and military methods. In these fascist antisemitic parties which, on the other hand, combat each other most furiously, often because of personal jealousy, one cannot see how things are. Here are the names of only a few of the Fascist Nationalist (völkische) parties who are participating in the election with their own candidates: German People’s Freedom Party, German Social Party, German Party in Baden, (National Socialist).

In the German People’s Party (Deutsche Volkspartei), in which the differences between the heavy industrialists and the industries which produce the finished articles have recently become more and more noticeable, there is a strong tendency at work on the part of Stinnes and Vögeler to form a National-Liberal union against Stresemann, thus following the tendency towards the right. At the last session of the German People’s Party in Hannover, Stresemann went a long way to meet the National-Liberal group of the heavy industrials he knows quite well

that, if the withdrawal of the leading great industrialist wing were to take place, his party would suffer a dangerous material loss, but whether he can prevent a falling apart of the German People’s Party is more than doubtful. Already in many places in Germany, National-Liberal candidates have been put up against those of the German People’s Party, and the appearance of National Liberals in the election is as good as certain.

Also in the Centre, things are getting very shaky. Having regard to the presence of so many socially different groups in the Catholic Centre, one would naturally expect that several parties would break loose, but so far this is only the case with the most active elements of the Christian workers in the Rhineland and Westphalia. Under the name of the “Christian People’s Fraternity (Christliche Volksgemeinschaft)”, the workers of the Centre are taking up a position against the capitalist group of the Centre and are going into the election with their own candidates. It is sometimes hinted that this group is merely a which safety valve has been opportunely opened by the clericals, in order to prevent the Christian workers going over to the Communist Party. In Bavaria where the Centre goes under the name of the Bavarian People’s Party (Bayrische Volkspartei), there is also a similar movement against the official policy of the Centre.

From the Democrats and the SDP., elements have broken away which promise to “defend” the republican gains of the revolution more energetically, than has so far been the case with the SDP. These constitute the Republican Party and the German Employees Party (Deutsche Arbeitnehmerpartei), both of which are formations which have naturally missed the historical opportunity, for there is need for almost anything in Germany except for new republican parties. These new organizations therefore only arise from the longing for seats by people who know quite well that there is nothing to be got from the old parties of the centre.

It is however well known that of all the parties, hell is really lose in the Social Democratic Party. The elite of the proletariat, the industrial workers, have long since left the ranks of this party, and it has long been a party of small bourgeoisie led by labour aristocrats in state service. If there are still groups of workers in it, it is thanks to the opposition of the “Left” under Paul Levi. But in the selection of candidates, Levi and his supporters have everywhere suffered glorious shipwreck. Up to this very day Levi has nowhere found a semi-safe constituency. His friends, former Independent Socialists (USP.) and former Communist Working Fraternity (KAG.), will almost to a man not reappear in the Reichstag. The “Left” has not only not had its wishy-washy opposition knocked out of it, but has even contributed the most by its spurious radicalism to make it possible for the SDP, in spite of the huge process of decay that is going on within it to go into the election, at least outwardly, united. Then there are three other Socialist parties which are recruited chiefly out of former Independent Socialists. There is the Independent Social Democrat Party (Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei), which contains the tattered remains of the old Independents; Ledebour, who was thrown out by these Independents, had to found a Socialist Alliance (Sozialistischer Bund) in order to be able to stand a candidate. Suddenly a Proletarian. Party (Proletarische Partei) has announced itself whose origin is still obscure, but which has already declared that it will place its own candidates in the field.

In order to give a full list of the competing parties, one must mention the separatist Workers Party in the Rhineland (Rheinische Arbeiterpartei), the Party of the Hanoverians in Hanover, and the Bavarian Peasant Alliance (Bayrischer Bauernbund). Added to these, are the parties which are grouped in accordance with guild and economic interests principles, such as the Economic Party (Wirtschaftspartei), the HouseLandowners (Hausund Grundbesitzer), and the Land Reformers (Bodenreformer) etc.

III.

The most outstanding characteristic of the whole party system in the German elections is thus the decay of the old parties and the continual rise and disappearance of new formations. That is all, however, merely an expression of the great fluctuations of the masses, which at first but vaguely are becoming conscious of the class antagonisms and feel themselves correspondingly drawn to new parties. It is natural that the sub-consciousness of the failure of parliamentary and. democratic systems which is present in the mass of the electors, also plays a great part, for never has the dissolution of a parliament given rise to such a sense of liberation, as was the case with the ending of the existence of the old Reichstag. Clever mandate hunters are making the utmost use of this feeling of dissatisfaction, first to the founding of new parties and secondly in an attempt to renew and strengthen bourgeois parliamentarism. It is necessary to send “the right men”, that is themselves, into parliament.

Opposed to this whole medley stand alone the Communist Party. Although after the October defeat, it of all parties had the greatest inner struggle for a new orientation, it still remains unexhausted and is becoming more and more a point of concentration for the proletariat which is breaking free from the democratic illusions. And herein really consists the task of the Communists, thoroughly to expose the meaning of the numerous formations of parties and the mandate hunters, and to prevent the growth of new illusions. The Communists will unmask the old parties of the Reichstag as the toadies of capitalism in the same way as they will characterise the numerous new nationalist parties as the harbingers of. a bloody fascism, and as they will pitilessly point out the folly of new left republican parties. In a phrase, the conditions of this year’s election are especially ripe for making use of the whole election campaign for the propagation of the principles of Communism.

The results of the election will show outwardly the sharpening of the class antagonism, i.e. the development of the dictatorship with its fascist and proletarian phases. The parties of the centre, of the great coalition will suffer great losses and most of all the SDP. Even Social Democrat newspapers count upon a loss of 50% so that the SDP. will not even retain 100 of its present 180 mandates. The defeat of the Democrats will also be disastrous, and in the same way the German People’s Party will have to give up large numbers to the extreme right. Even the Centre which, according to experience, is usually the best off, is bound to lose a certain number of seats. That those new democratic parties which give themselves proletarian airs which have been mentioned above, will obtain a mandate in any constituency, is practically out of question.

On the other hand the new fascist nationalist parties will be able to show great success with their social and national demagogy, although the old German Nationalists will also show a great increase in seats. It is reckoned, there will be about fifty members of the new fascist nationalist parties. The number would be even greater, if it were not for the great splits in this fascist movement.

Parallel to the gains of the extreme right, there is the consolidation of the best part of the proletariat in the Communist Party. The sixty to eighty seats which will fall to the Communists, will be the expression of the fact that the German Communist Party has become the undisputed leader of the proletarian masses who are pressing forward, not only for the moment of the election struggle, but also for the inevitable deciding struggle between Labour and Capital.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecor” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecor’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecor, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1924/v04n25-apr-17-1924-inprecor.pdf