The Mexican Revolution was a hugely influential and radcializing series of events for U.S. revolutionaries. Carleton Beals was among the most important of the U.S. chroniclers of the Mexican Revolution, with his articles informing a generation of U.S. activists on the history-making events next door.

‘The Mexican Revolution’ by Carleton Beals and Robert Haberman from the Liberator. Vol. 3 No. 7. July, 1920.

Robert Haberman, formerly of New York and a member of the Socialist Party. has spent the last few years in Mexico, organizing co-operatives in Yucatan. Carleton Beals is another New York Socialist whose name will be familiar to many of our readers. We hope to print other interpretations of the Mexican situation in the near future.

AFTER ten years of practice any people should understand quite thoroughly the technique of conducting a respectable, eat-out-of-your-hand revolution. The Mexican revolution which brought a new régime into power some few days ago was orderly, efficient, easily successful. Less than a month from the day the sovereign state of Sonora raised the banner of revolt, the revolutionary army–el ejercito liberal revolucionario–galloped into the capital without the firing of a single shot.

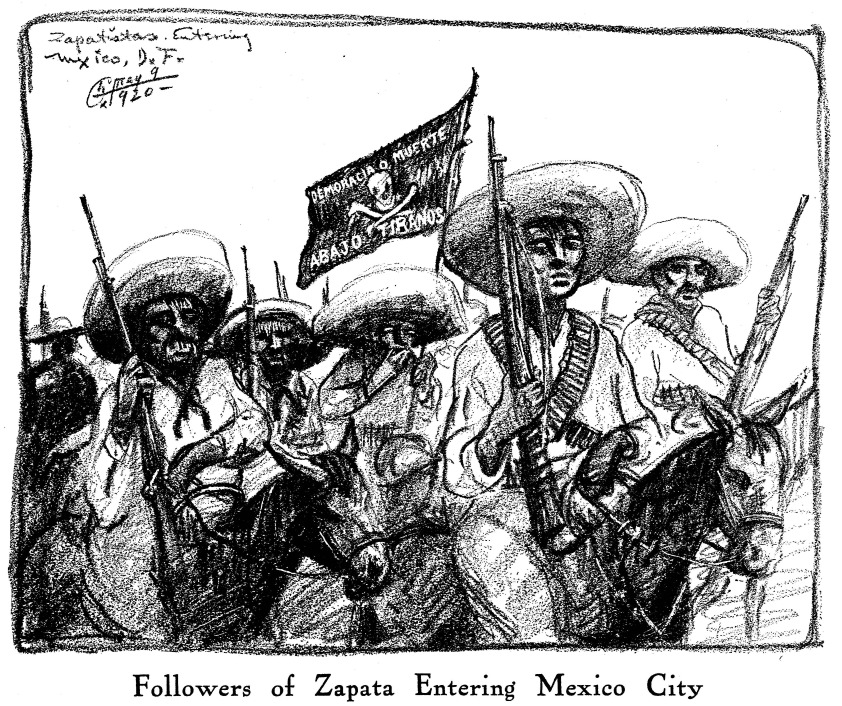

They looked strange–those men from the hills, on their lean, tired ponies, as they pounded down Avenida Francisco Madero, Mexico’s fashionable Fifth Avenue, dusty and ragged–colorful with great red and blue bandana handkerchiefs and vivid shirts, with flowers hung on their carbines, but eyes grim with purpose. Yet Mexico paid little attention to them. The stores were open; the honking automobiles crowded the flanks of their ponies; fashionable women went unconcernedly about their shopping. Only occasionally did they stop with a rustle of their silk gowns to gaze at the queer outlaw crew of sandalled Indians and Mestizos sweeping by beneath their great, bobbing sombreros.

During those first days I roamed the streets disconsolately–box seats at a Mexican revolutionary melodrama and no thrills. I tried to imagine the turnover as being a cross-your-heart-to-die proletarian revolution, but merely spoiled the afternoon wishing I were in Russia.

Nevertheless, I made the most of it; hired an automobile and dashed around town taking snapshots of generals–who were easier to find than soldiers–scoured the countryside looking for the victoriously approaching Obregon who was expected in the capital within forty-eight hours with an immense force, of which the bands of cavalry we had seen were the paltry forerunners. Early in the afternoon we burnt up the road to Guadelupe Hidalgo–that venerated religious mecca of Mexico five miles outside of the capital, whishing past red-cross machines speeding back from the wreck of one of the Carranza military trains that had evacuated the capital some twenty minutes before the rebels arrived.

Four of the eleven Carranza military trains had been stopped in the Valley of Mexico; one by the treachery of its commander who voluntarily surrendered it; a second by a few well-placed shots; a third by a smash-up made by a crazy locomotive let loose in pursuit like the grand finale of an impossible ten-cent movie thriller; and the last by the sabotage of the workers.

The last was the most significant. Although this revolution has been a cuartelaza, or military revolt, although the people have been so disillusioned during the past ten years as to be full of skepticism towards any government, the universal and bitter hatred of the peon and the worker towards the cruel Carranza military regime has been so strong that their sympathies have inevitably been thrown with Sonora, with Obregon, with the revolutionaries. Perhaps had the debacle of the Carranza rule not been so swift and so easily accomplished, this might have been a new revolution by the people.

Yet even so there is no assurance that this revolution will be any more successful than those, that during the last ten years have passed like great suffocating and devastating tidal waves over the heads of the very ones who have made them, or at least been the cause of them–the bewildered, helpless, idealistic Mexican people–except for one thing: this revolution brings for the first time since the downfall of Diaz a real welding of the rebel movement and counts upon its side every man of decency and vision–such as it is–that has appeared in Mexican life during recent years–de la Huerta, governor of Sonora; Calles, leader of the Sonora revolt, and but a month previous a recalcitrant member of Carranza’s cabinet in the portfolio of Commerce and Labor; Alvarado, the State Socialist of Yucatan; Felipe Carrilo, president of the Yucatan Liga de Resistencia. Any social progress in Mexico depends, for the present, absolutely upon the calibre of the leaders. “Democracy” and “The People” are meaningless terms so far as politics go.

But already, a week and a half after the capital was taken, before a provisional president was elected, the new leaders began to see that the people got lands. I attended an enthusiastic ceremony in Xochomilco, a suburb of the capital, but yesterday, where 3,000 acres of the finest land in the valley of Mexico, the ancient ejidos or commons of the village, were returned to the Indians.

The French Revolution failed, from a constructive standpoint, because for over one hundred and seventy-five years the people had had absolutely no experience in local or national self-government, no training in cooperative and voluntary association; the Russian Revolution succeeded, not alone because it moved upon the afflatus of a great and consuming ideal, not alone because of the driving impetus of economic and historic forces, but because the, peasants of Russia had already tasted the flavor of local self-government, because they had already learned to work together in co-operatives and soviets. The Mexican is in the same situation as the French peasant of the eighteenth century, just as helpless in the clutch of ambitious and selfish personalities. The one good thing that the years of revolution have thus far brought the Mexican, is not land, not a better standard of living, for in both respects he is worse off than in the days of Diaz, but an abiding sense of freedom and conviction of his inalienable right to enjoy freedom. Part of this determination to attain true freedom has fortunately been expended in creating labor organizations, weak it is true, but promising. But as yet the people of Mexico, however frequently they make a revolution, or permit themselves to be used to make one must depend upon their leaders for the fruits.

The latent sympathy of the workers and the peasants is with the new movement because of the personnel of its leaders. The sabotage on the part of the railway workers is one proof of this latent sympathy. The Carranza train was stopped because some of the workers in the round house saw to it that one of the engine trucks would drop off within a few miles. It was the railway workers who helped Obregon to escape from the clutches of Carranza, and during the past month scarcely a military train has left the capital that has not been so sabotaged by the workers as to guarantee a break-down and a temporary blocking of the way. Also perhaps it is more than a coincidence that the workers of the textile mills of the Federal District went on strike during the revolution, and that a general strike was imminent in the capital just before the fall of Carranza. For even the poorly organized, uneducated workers of Mexico are beginning to discover that there are more effective ways of making a revolution than by bullets and self-slaughter.

It was to be expected that the workers would hate Carranza. There has never been an important strike in Mexico, but that Berlanga, Carranza’s sublimated office boy, has not sent federal soldiers to shoot down the workers or invoked or threatened to invoke the treason act.

In Yucatan the government troops have broken up with torture, murder, fire, and hanging, the great Liga de Resistencia, an organization having 67,000 men and 25,000 women members, paying a monthly dues equivalent to seventy-five cents. Its co-operative stores were looted, and machine-guns turned upon whole villages.

To the Yucatecan the red card of the Liga meant land and liberty. He had stripped his churches of their images, and had used the buildings for headquarters and meeting places for the League. He carried the card in the crown of his mammoth sombrero with the same religious veneration that he formerly carried his image of his patron saint about his neck.

When, therefore, the federal Colonel Zamarripa rode into a village, as he did into Mixupip, and announced to the villagers that they were to call themselves Liberales, or members of the government party, they demurred. In Mixupip he strung five of them up to the nearest trees as an example to the rest.

“Now, what are you?” he then bellowed.

The Indians, unshaken, naïvely pointed to the red, cards in their hats.

Colonel Zamarripa shot twenty–for a lesson!

In this way whole villages were wiped out, until 1,200 members of the Liga had been murdered.

Even the reactionary Mexican Senate protested to Carranza. Carranza retorted by making Zamarripa governor of the federal territory of Quintana Roo.

Aside from cutting off the heads of election inspectors and putting them on top of the ballot boxes; aside from threatening with death everyone who did not vote, and forcing everyone that did vote, to choose the government candidates, the Carranza government was quite honest, humane and enlightened in Yucatan.

Read what the daily paper La Revolución said last February about the governor of Oaxaca, one of the richest states of Mexico.

“The governor Juan Jimenez Mendez is the protecter of lives and haciendas (in Orizaba). That governor assassinates, orders assassinations, burns towns, hangs pacific townspeople, steals the municipal funds to maintain his automobile and fine living. As a result many employees die of hunger because he does not pay the salaries honestly earned. He–Jimenez Mendez, like a ridiculous dude, changes his suits daily, organizes gambling, and, with his gang of followers, becomes obsequious to anyone who brings gold. He takes trips when and where he pleases, and fails to come to his office for two, three, or as many as five days.

“The fields are stripped of their fruits, private persons are attacked during the early hours of the night within three or four streets of the state capital building…

“This “misgovernment” is surrounded by pimps, vulgar, elegant women, ignorant idlers…”

There have been a great many myths regarding the benefits of the Carranza régime, such as the opening of schools, giving lands to the Indians, nationalizing the sub-soil, etc., etc. One by one the pitifully few schools of the Diaz administration have been closed until Tacubaya and Mixcoac, two of the largest residence suburbs of Mexico City cannot boast a single public school. Land, given to the Indians, has in many cases, as in Yucatan, Tabasco and Morelos, been wrested away by military might, while a single grant to a General has often amounted to more in area than all the lands given away to the people during the whole of the Carranza rule. Under the cloak of the slogan of Mexico for the Mexicans, which has so attracted the imaginations of American radicals, he has stabbed every liberty in the back, and has built up a grasping, grafting, unprincipled military clique, the members of which have ridden across the land looting, murdering and stirring up revolt, until the federal soldier is more feared and hated than the bandit.

Directly the revolution resulted from two things: the attempt on the part of the government to railroad Bonillas, former ambassador at Washington, into the presidency; and the attempt to repeat the story of Yucatan and its murders in Sonora, the home state of Obregon.

To guarantee the election of Bonillas, government candidates were imposed by force in half a dozen states, Obregon meetings were broken up by the sabers of the man on horseback, Obregon himself was arrested on fake charges of inciting a rebellion. The knowing shook their heads, and predicted his murder within a week or two.

In the meantime Carranza was pouring soldiers into Sonora, against the repeated remonstrances of Governor de la Huerta, to crush the railroad strike and several mining strikes that were on, and probably in addition to break up the state government and impose his own officials as he had done in Yucatan, in Tabasco, in half a dozen other states.

Obregon saw that the time to act had come. To do so, he had to escape from the sleuths that hounded him day and night. This was difficult as he is well known and easily recognizable because of his having lost an arm in the battle of Celaya. One night he held a conference with General Gonzalez at the Chapultepec Cafe on the edge of Chapultepec park. About eleven o’clock his party left in their machine, but instead of returning to the city took a spin about the park. The sleuths in autos followed close behind. In the shadows of the park Obregon changed the big sombrero he always wears with the smaller felt hat of one of his friends, and, watching his opportunity, jumped from the slowly running machine behind a hedge. The auto proceeded on its way, and returned to Obregon’s house. Apparently Obregon left the car, and his friends called “Good-bye, Alvaro,” as the machine swept away from the curb. The sleuths did not become suspicious until the following day.

Meanwhile Obregon went to an appointed spot in the park where a railway worker met him with a big cloak. They went to the latter’s house, where they waited until half-past four in the morning. Obregon slipped into overalls, tied a big, red bandana about his neck, picked up a lantern and with his friend sallied forth to the station. In spite of his missing arm, he passed two guards, with a cheery “adios,” and a swing of his lantern in their faces to blind them, and jumped on the waiting train. An express agent concealed him in his car, and he was off to Michoacan.

In Michoacan the banner of revolt was easily raised. The governor of the state rushed to his side with troops. The Yaqui Federals, all his friends, deserted. Within a week he had thousands of armed men at his disposal.

Obregon fought his way down from Sonora, through the states of Sinaloa, Nayarit, Guadalajara, direct to Mexico City in the tragic Huerta days of 1914. He is an impulsive, determined, Rooseveltian type of man, but with a social consciousness. There are many stories afloat regarding his hasty actions when he governed the city of Mexico towards the end of 1914. An American told me with horror that he even made the owners of fashionable shops on Francisco I Madero Avenue, get out and sweep the streets during the days when the city was without street-cleaners.

“Why, that is Boishevikeeeeeeee,” she cried, and agreed with her.

It is certainly true that he did not mince matters with the food speculators. He called the owners of all stores and factories together one day, and told them, General Hill acted as his spokesman–first, how they were to treat their employees; second, that any dealer caught speculating in the necessities of life would be taken out in the plaza and shot. The harshness of this is not so apparent when the truth is told that the food merchants were running the prices up to fabulous figures. Poor people were dropping dead on the streets from starvation, and every morning their bodies were run out of the city on a flat car and burned. The merchants answered his declaration by closing up their shops. Obregon then told his soldiers and the people to go help themselves. He might have made a more intelligent solution of the problem, but the incident shows the temper of the man, and in any event, food-stores have ever since been a bit careful about boosting their prices. When the rebels entered the city on May 1 under General Trevino his first edict was to the effect that all legitimate business and industry might continue operation without fear of molestation, but that all speculators in food stuffs would be drastically dealt with.

Very early Obregon began to doubt the good faith of Carranza, who showed no inclination to enforce the Constitution of Queretéro, which contains the most enlightened labor code of any capitalist country; who manifested no desire to satisfy the agrarian claims of the states south of Mexico under the revolt of Felix Diaz, and Mixicuero. One day Obregon left his post as Secretary of War and accepted the job of mayor to the little village of Kuatabampo in Sonora. The act was typical of the impulsive man.

Last Sunday he rode into Mexico City at the head of twenty thousand rebels between the crowds that jammed the road from the suburb of Tacubaya to the capital. He passed up the fashionable Paseo de la Reforma with a six days’ growth of beard, wearing an old shirt and–SUSPENDERS. He has taken a shave since his arrival, but he still wears the suspenders about the capital–and the same shirt. We are all hoping he has another and will take a change soon.

Obregon is the idol of the lower classes. Yet he has few of the ingratiating tricks of the professional politician. As he passed through the cheering multitudes, he rarely bowed or smiled, or gave the slightest sign of recognition.

At the caballito, which is a great iron statue of Charles the Fourth, at the big circle which marks the junction of the Paseo de la Reforma and the Avenida Juarez, in the amphitheatre made by the great Heraldo de Mexico Building, the American Consulate, the St. Francis Hotel and the Foreign Relations Building, Obregon made a few brief remarks–he is not a speech-maker–changed his horse for an auto and hurried up to the National Palace. As he entered the Zocalo, the broad National Plaza, beside which stand the City Hall, the Capital Building and the great Cathedral, the peons who had crowded up into the balconies of the latter began ringing the great brazen bells. All afternoon and evening they flung the sonorous, heavy sounds across the flat-roofed city. But Obregon did not stay to receive homage, rushed past in the auto, with a salute to Gonzales, who had been talking for a wearisome length of time, shouted half a dozen sentences to the crowd, and was gone, a band of Zapatista cavalry pounding hard behind in attempt to keep up.

Obregon has learned much since he entered Mexico City in 1914. Six years added to a man’s life when he is in his thirties, six years full of experience and action, mean everything. To-day Obregon is probably as determined to put his ideas into practice as he was when he took up arms against Huerta, but he has seen the folly of following certain courses. His manifesto, issued in Michoacan–and this will come as a shock to American radicals, although Carranza made the same statement in trying to get American recognition–declares, that foreign capital will be given every protection and guarantee, and that its holdings will not in any way be molested. But whereas Carranza made this statement and, did not keep his word, Obregon is determined to make good the declaration, and for the following reasons: Mexico cannot put across one measure of real social reconstruction if the government has the opposition of American capital.

On the other hand, Mexico is the richest land on the face of the earth so far as resources are concerned. That is her worst crime. She would ere this have been peaceful and prosperous had her people had to struggle for their existence against the barrenness of the soil. But Mexico is so rich, and her resources so unexploited, and those in the hands of foreign capital so little in comparison to the total wealth, that Mexico can afford to say to foreign capital:

Keep what you have. With the remainder we shall build a modern social edifice, we shall give lands to the people, we shall establish schools, we shall teach our people to organize themselves into labor unions; we shall carry the real meaning of the revolution to every pueblo, until we leaders shall have such an enlightened backing as not to fear the instigated revolts of foreign capital. If we give land to the people, the surplus labor supply will be cut down, for the Mexican is instinctively, fundamentally agrarian. Foreign capital will have to pay decent wages to get workers.

This may be wrong reasoning. But the Mexican stands eternally in the fearful shadow of armed intervention. He knows that it would take very little to precipitate it. Should he institute a real social revolution such as we have witnessed in Russia–and that is impossible because the people are not organized for it–intervention would come with the suddenness of their own tropic storms. Such a social revolution would perish in blood and iron, militarism would again be in the saddle in the United States, another India would be born, with a more tremendous race problem to solve than exists to-day in the south.

There are other interesting personalities behind the new revolution–Calles (pronounced Kah-yayz), for example, ex-military governor of Sonora, Secretary of Commerce and Labor and leader of the Sonora secession. He is without doubt the most forceful, the most radical, the most intelligent and widely informed among the present leaders of Mexico.

As governor of Sonora he proved himself a champion of labor, and he gave the Indians lands, and each a gun and five hundred rounds of ammunition with which to protect and hold them. Carranza immediately telegraphed him, when these acts became known, to take back the lands. Calles replied: “Send a stronger man than I am, for I can’t do it.” Calles has tried to enforce Article 123 of the Constitution, which is the most enlightened labor code of any capitalist country. As a result the Phelps-Dodge Company, which operates the great copper mines at Cananea, closed their works. Calles instructed the workers to take charge of them and run them. He told me how surprised he was to see how well they did it. The representatives of the Phelps-Dodge Company hurried back upon the scene with a great bill for damages. Calles admitted their claims, but then he turned to the Mexican constitution.

“I read here,” he said, “that any company that ceases operations without giving two weeks’ notice must pay three months’ salary to its employees. Go bring your payrolls, and we will strike a balance to see how much YOU owe the workers, whom I represent.” The mine representatives decided to return to Cananea and put in safety appliances, build club rooms, reading rooms, and, to crown all, a huge concrete swimming pool for the workers.

“Do you know of any other mine in the world that has a swimming pool for its workers?” Calles asked me as he told this story, and then he laughed. At the same time the same company, just over the international line in Bisbee, was driving its workers, across the heat-eaten sands of the desert. so Calles, not being able to enforce Article 123 in the civilized United States, did what he could by sending food to the unfortunate victims.

Some mine owners down in Sinaloa had not heard of these things. They sent to Calles asking him if he could supply them with some good docile workers. He picked out the most intelligent union men he could find in all Sonora and sent them down to work. Within a week they had the Sinaloa workers organized and on strike to demand decent conditions.

Perhaps the most striking accomplishment while he was governor of Sonora was his ability to pacify the Yuaqui Indians, something that had not been done even in the days of strong-arm Diaz.

When Calles came to Mexico City to act as Secretary of Labor, I went to him, having heard of his work and his attitude, with a copy of Bullitt’s report on Russia, hoping to have him translate and publish it. He laughed when I mentioned it, and, turning to his books, said:

“Here it is. I just finished having it translated. Great stuff, isn’t it. I’m going to have it printed as one of the documents of the Labor Department.”

But it was never issued. (Portions appeared in a Yucatan paper.) Blocked at every turn in his efforts to enforce the Constitution, he finally resigned his post and went back to Sonora as a private citizen to organize the workers. Carranza, perhaps having learned from peacock Wilson the possibilities of governing without a government, called no cabinet meetings while Calles held the portfolio. Calles could not enforce the eight-hour law, the minimum wage, workers’ insurance–he could not even appoint a single factory inspector. By the most strenuous efforts, he prevented Carranza from sending machine guns during the great strike of textile workers in Orizaba. He boldly took the side of the workers and informed the factory owners that if they did not grant the strikers’ demands the government would take the factories over and run them. That ended Calles with Carranza.

One of the most picturesque figures in the new movement is Felipe Carrillo, ex-president of the Liga de Resistencia of Yucatan, who has been fighting out in the hills of Zacatecas since the revolution started.

Felipe began his career as a radical in the days of Diaz. As some people have thought to their sorrow in the United States, he believed that the Constitution of the nation might be distributed to the people to be read. Accordingly, he translated the Constitution of the land, the enlightened Constitution of the great old Indian, Benmerito Benito Juarez, into the Maya dialect, and began reading it on the great haciendas. He went promptly to jail. The Constitution was a sacred and holy document, not to be profaned by public sight and hearing, a document that was to be kept in the national archives and the Biblioteque Nacional, and only taken out on special occasions for the hoary and erudite sages of the Supreme Court to peruse slowly and solemnly and con dignidad that they might write lengthy, weighty and incomprehensible decisions for the proper guidance of the dear people.

In six months Filipe was out–and mad. He began making speeches to the peons on the haciendas. His brother-in-law, however, was a rich hacendado who believed that freedom consisted in his right to put chains on the legs of his peons. His brother-in-law loved radicals. His brother-in-law sent a man to kill Felipe. The man fired at Felipe in a public meeting, but missed. Felipe pulled his gun and shot the man dead. Felipe went to jail for manslaughter.

When Alvarado came to Yucatan, Felipe was released, and set to work ardently to organize the great Liga de Resistencia, which Carranza later destroyed with murder and rapine.

I remember listening to Felipe addressing the Indians one Sunday. He knew the old religious superstitions of the decades of the domination of the Spanish Church and State must be broken down before he could form any real radical organization. It was a subject that always required careful handling. I remember how cleverly he worked up the subject until he had the Indians with him. I remember how he cried out:

“For the love of Jesus you used to get up at three o’clock in the morning to go to work; for the love of Jesus you were whipped to work; for the love of Jesus your women were raped by the hacendados; for the love of Jesus you were hungry and ragged; now for the love of the devil you have happy homes and bread and your own bit of land.

I remember how the plaza rocked with the shouts of: “Viva el Diablo, viva el Diablo!”

Perhaps that is why, among other things, the Mayas turned the churches of the Conquest into meeting places for the Ligas de Resistencia.

I met Felipe immediately he came to Mexico City just after he had been forced to flee for his life, when federal troops had flogged one hundred of his neighbors in the public plaza of his home town. Murder was tearing Yucatan in its teeth; rapine was stalking in blood across the Peninsula.

Felipe was heart-broken. His beloved Indians had been shot down by hundreds on hundreds. The work of years had been destroyed in a few months. He felt himself back in the Diaz days.

“All is lost,” he would groan, “all is lost.” He had no spirit for anything. He scarcely cared to live.

I met him again when he came back from the hills of Zacatecas, brown and hard as nails. He was the same old Felipe again–joyous, over-optimistic, enthusiastic. He was burning to be off to Yucatan.

“This time,” he vows, “I will do as Calles did in Sonora–give the Indians lands and guns. All Mexico and all the world will not take our rights away from us a second time.”

There is a sentiment among all the leaders behind the new revolt to give the people land–Obregon, Calles, Carrillo, de la Huerta, provisional president and ex-chief of cabinet; Villareal, the most uncompromising agrarian of the revolutionary period, and now to be named Ministro de Gobernacion, Soto y Gama and Magaña, for ten years irreconcilable Zapatista leaders–all have made public statements in favor of allotting available lands to the people immediately. This work has already begun, in fact, a few days after the revolution.

To-day, for the first time since Madero, the trains of Mexico are running on schedule without military escort. Every rebel, except the impossible Villa, has pledged support to the new movement–Palaz, the autocrat of the oil district, who is to be quietly side-tracked; Soto y Gama, the lawyer who has been fighting for ten years in the mountains of Morelos for land reform; Mixieuero, the peasant leader of Michoacan.

A cuartelazo is not a social revolution, and giving lands to the Indians is not Socialism, nor is it the ultimate solution of Mexico’s problem. But it is not too much to say that never before during the past ten years of Mexico’s checkered history has an event so fraught with social significance occurred as the recent “commotion,” which changed the personnel of the government. Progress for some time to come in Mexico must depend upon such changes of personnel–until some form of political and economic organization is built up among the people. The present leaders have promised to further that organization, to permit labor to organize, to teach the peasants to form co-operative associations. It has been proposed to establish a national minister of propaganda, who will carry the meaning of the revolution to every village and pueblo of the country; to establish training schools for developing men who can carry on the reconstruction work that faces the country. Mexico is beginning to realize to-day that the failure of the Madero revolution is to be found in the lack of organization among a people, and if the present attempt is to succeed it must fill this void which is the origin of military intrigue, cuartelazas, foreign machination and a goodly part of the menace of intervention.

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses, was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. An essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1920/07/v3n07-w28-jul-1920-liberator.pdf