Jacob Margolis, one of Pittsburgh’s leading pre-World War One radicals, guides us on this wonderful tour of that city’s revolutionary working class history. A resonate, vivid narrative of the 1912 Free Speech fight by Socialists and industrial unionists in what was a central industrial region of the country and home to great class battles.

‘The Streets of Pittsburgh’ by Jacob Margolis from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 13 No. 4. October, 1912.

TO MANY Pittsburgh appears as one of the most conservative labor centers in the United States. Being the center of the steel and coal it is supposed to be continually boiling and sputtering, and when these manifestations are not apparent many think that the city is asleep. The first indication in a long time of any outward animation was about by the Free Speech Fight. The cause is not definitely known. Some have ascribed it to the Flinn Machine, that notorious political organization of ma- chine politics, which even in Pennsylvania is malodorous. Others ascribe it to the Catholic church, and because of certain circumstances in the immediate neighborhood of the Free Speech Fight there seems at first blush to be some justification for this.

I am inclined to believe that the cause is a more profound one and that the objection of the authorities to the Socialist party holding their meetings at Kelly street and Homewood avenue in the city of Pittsburgh is merely one of the significant details of the whole situation.

Those who live outside of the city and know of Pittsburgh by report must necessarily get many erroneous impressions of it. Pittsburgh is a gigantic workshop where the greatest number employed are unskilled. Craft unionism, although it makes a pretense of being strong in the community is in truth very weak. The mining industry which is supposedly organized under the American Federation of Labor is not a craft union at all. The essential character of Craft Unionism in this industry is lacking because it is not an organization based upon the skill of the workers employed. In the steel mills the greatest number are unskilled. In the Westinghouse industries the vast majority are actually unskilled workers. In addition to these facts the Homestead Strike of 1893 gave to labor of the Pittsburgh district such a severe blow that it seemed hardly possible that labor would ever again be able to hold up its head and battle with capital.

The great industrial establishments in Pittsburgh although they proclaim in and out of season their unalterable and undying love for the American nevertheless have in practice the seemingly inconsistent habit of employing the “Hunky.” The mines of the Pittsburgh district are operated by “Hunkies.” The mills of the Pittsburgh district are operated by “Hunkies,” and most of these “Hunkies” are not citizens and have no vote. This apparent sleep of Pittsburgh is not a sleep at all although these workers cannot make big displays by electing Socialists to office.

The Pittsburgh Free Speech Fight has a more profound significance therefore than we would think at first blush. Homewood is one of the residential districts of the Westinghouse industries. It is a peculiarly militant district. The branch of the Socialist party at this point is known as the most revolutionary in Allegheny county and their meetings on the streets have been along industrial lines. As long as they confined themselves to the discussion of politics it seems that they were not molested but as soon the character of the subjects discussed, changed, the authorities discovered that it was high time for them to put a stop to the whole business. They found no difficulty whatsoever in “cooking up” an excuse. It was no difficult matter to persuade or intimidate a few weak-kneed business men to make affidavit that their business was being interfered with and scarcely any pretext at all was needed. With the complaints of these business men in their pockets they felt justified in refusing the speakers a permit for the corner of Home- wood avenue and Kelly street in the city of Pittsburgh.

Free Speech is a valuable asset. To be deprived of it means that secret methods must be employed and the latter are hardly ever successful. It goes without saying that it is well nigh impossible to carry on an effective propaganda when the power of granting or refusing a permit to speak on the street is left to the discretion of a police official who may object to the cut of your coat or the color of your necktie. This is apparently what has happened in the city of Pittsburgh. They do not like the distinctively “red necktie” that was being worn by those who spoke at the corner of Homewood and Kelly.

Meetings had been held on this same corner for three years without any very strenuous objections being raised, but a very strong wave of industrialism has been passing over the city and many of the “red necktie” wearers of Homewood were stricken with the revolutionary fever and once having been stricken they pro- posed to contaminate and infect everyone who came in contact with them. Our overzealous and solicitous police officials, the preservers of the peace, health and morals of the community, immediately proceeded to place a strict quarantine and insisted that no meetings could be held in any populous section because реr chance this contagion might spread and do irreparable damage. They were told to go to Kelly and Lang Avenue, where not even as many as five people pass in as many hours.

The first hostilities broke out on August 3d last, when Comrades Merrick and McGuire were arrested for speaking with a permit. The quarantine was already on but unknown to the comrades, and they proceeded to talk Socialism, for which disobedience they were arrested and fined. Immediately after this the permit was revoked. The ardor and enthusiasm of the comrades did not abate in the least. They concluded after deliberation that they would hold a meeting at the corner of Kelly and Homewood despite the failure to procure a permit.

They had met at this place for three years and felt that if it were lawful to meet for three years it was lawful to meet for three years and one week. But the police officials thought otherwise and the comrades not having the “legal and holy” permit were arrested to the number of twenty. At this meeting, on August 3d, there were approximately ten thousand people in this quiet residential district of Pittsburgh. They came there to protest against the action of the police department; to protest against industrial slavery; to protest against capitalism; to protest against tyranny. They did not protest boisterously or loudly or profanely, but rather silently and with a grim determination. They employed that great weapon of Passive Resistance. They gave the police department no excuse for arresting anybody, but the police, “eternally vigilant,” “preservers of the peace and tranquility of the community,” did their “sworn and bounden duty.” Nine girls and women and eleven men were lodged in a cell room. The next morning they appeared before Police Magistrate Fred Goettmann and were all discharged. The magistrate told them that they could meet without a permit, for which breach of obedience it is rumored this magistrate was removed to a different part of the city.

The comrades, still undaunted, decided to meet on the 10th of August and this was the memorable day of the Free Speech Fight in Pittsburgh. It is estimated that there were fifteen thousand people on the streets on this night. The order preserved was well nigh perfect. Some of the police had surrounded the speakers’ box and as Comrade Mervis, the speaker of the evening, was mounting the stand, he was arrested. Forty-four others were arrested with him. All told there were thirty-eight men and seven women arrested that night. In the six cells of the cell room at the Frankstown avenue station there were eighty-one men, from eleven to fifteen in each cell room. It is hardly necessary to describe the conditions of this cell room. The men could neither sit nor lie down. The odors of drunken, filthy men were intensified by the complete lack of ventilation, for the turnkeys, fearing lest the men would jump out of the windows, notwithstanding steel bars were in their way, closed all the windows.

The raid of the police was marked by several dramatic scenes that really mark the events as historical. One of these occurrences was when an automobile was brought into service suddenly and a man with a megaphone was rushed through the crowd unexpectedly and announcements made before the police realized what was being done. As a result the crowd was quickly gotten onto a vacant lot to the discomfiture of the police.

Another moment and perhaps the most dramatic of all was when, while the mounted police thought they had guarded off a block of the street, suddenly there appeared in the middle of this block from an alley a Socialist band led by a slender girl, Elizabeth Hobe, who was waving a red flag as they marched right down through this square. It did not stop playing until the players were placed under arrest and taken to the depot. As the train pulled out the tenor drummer stood on the rear platform and drummed the Marseillaise in ridicule to the chagrin of the police.

One of the pathetic and inspiring events was when Mrs. McAllister, a woman 52 years of age and of frail health, refused to accept a forfeit which would result in her release on the night of her arrest. She refused this and insisted on remaining all night as a protest against the conduct of the police.

The girls who have been especially trained in literature hustling seized upon the assembling of these thousands to go along the street and sell JUSTICE on the street and sub-cards instead of marching in a procession.

Another view of the picture, the most inspiring, which should not be forgotten is the two hundred, perspiring, angry, foot policemen, led by their superior officer like automatons, walking here and there, following the crowd, unable to arrest anybody for want of provocation. Then there was the beautiful awe inspiring spectacle of thirty mounted policemen filling the street from curb to curb riding through a peaceable crowd pushing them on to the sidewalks and against the buildings. The question comes to our minds, why all this expenditure of money on the part of the officials of the city of Pittsburgh? Why this terrible engine of oppression brought into play? Why was a peaceable residential district turned into a “busy metropolis”?

The fight at this writing is still going on. An appeal has been taken from the decision of the magistrate who fined Comrade Mervis twenty-five dollars for speaking without a permit. In the meantime the police officials feeling unequal to the task went into court and the court granted an injunction restraining all persons from speaking at the corner of Kelly street and Homewood avenue. That most pernicious instrument of capitalist law, the injunction, figures again in the struggles of the working class. When the capitalist has exhausted all his efforts along legal lines he resorts to that most potent, certain and speedy weapon, the injunction, and our judges have not been notoriously guilty of refusing to issue it when asked by the capitalist to be used against the workers. The fight is not in the courts, for the workers are not deterred by any decision rendered against them.

Primarily it is the purpose of the conscious worker to enlist the cooperation of the other workers and secondly to enlist the sympathy of all liberal minded persons. A great wave of public sentiment in a community, a great demonstration of protest is very much more effective than a court decision, and even though the courts of Allegheny county and the state of Pennsylvania decide against the workers, they have not lost, for they have succeeded in arousing a storm of protest, have succeeded in doing such effective propaganda work by the Free Speech Fight that we cannot estimate its value.

They have established a significant precedent and an arbitrary police official will think twice in the future before attempting to discriminate against the revolutionists. He will know that he has a bigger job on hand than he bargained for. More than this, it has shown to many workers the value of Mass Action, the value of Passive Resistance and the necessity for organization among the workers along all lines.

Pittsburgh has not been a particular star in the political firmament, but things are brewing here. Revolt, real industrial revolt is in the air. The Pittsburgh politician has promised many things and has never fulfilled a single promise.

The woods are full of Revolutionary Socialists and Industrial Unionists and the Free Speech Fight is merely a skirmish in the Industrial Revolt about to follow. I am satisfied that had Homewood remained a political center and not become a hot bed of industrial unionism that the trouble never would have occurred. Industrial organization is going on all the time in the Pittsburgh district rapidly enough to bring all the forces of capitalism into play against the revolutionary workers. The working class can under no circumstance lose, for in struggles like this, the worker learns what strength he possesses, who are opposed to him and what measures will be taken to injure, oppress and if necessary exterminate him.

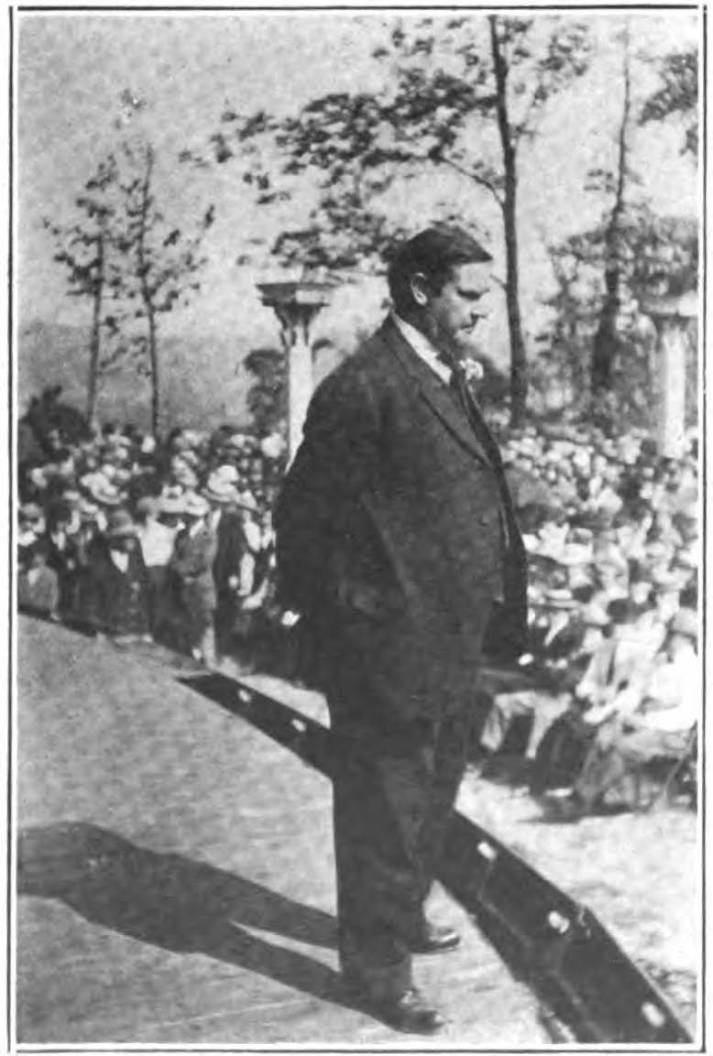

Just at the time when public opinion was at its highest pitch in Pittsburgh over this fight Bill Haywood came into the Pittsburgh district and on Sunday, August 25th, there was a giant Ettor Giovanitti protest meeting at Kennywood Park which was attended by at least 15,000 people. The weather was ideal and the grounds overlooked the great Steel Trust plants of the Edgar Thompson steel plant and American Steel & Wire Company at Rankin, on the opposite bank of Monongahela plant the and in the distance the historic battleground of labor-Homestead.

This great auditorium in the midst of these industrial plants was the ideal place for the discussion of the latest development of industrialism. Haywood spoke twice and his speeches were most remarkable and made such a deep impression upon the audiences that the moral effect will be felt for years and quite possibly the suggestions made there will shortly result in a great general strike throughout the Pittsburgh district.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v13n04-oct-1912-ISR-gog-ocr.pdf