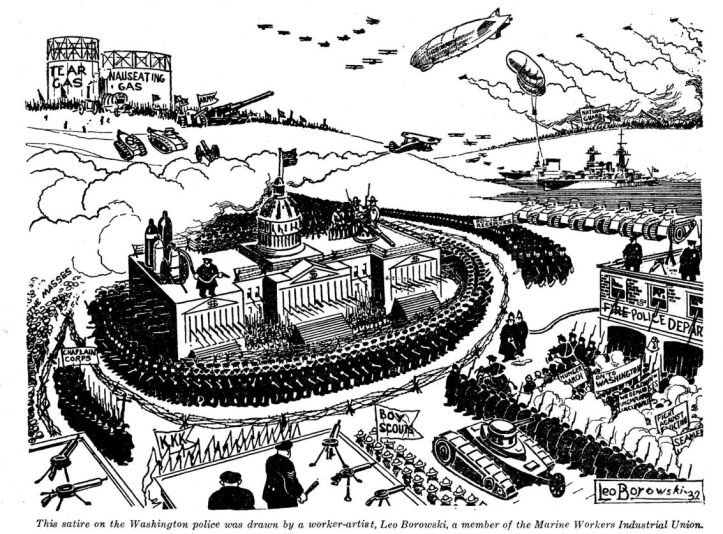

The ‘war-ravaged Portland’ of 1933. Felix Morrow exposes the slander, instigation, and reactionary intentions of the ‘kept press’ over a Hunger March for relief in Washington D.C. during the Great Depression. As some wise comrade said: it may be worse now, but it wasn’t better before.

‘The Press Lies About the Hunger March’ by Felix Morrow from New Masses. Vol. 8 No. 6. January, 1933.

Misrepresentation of the character and conduct of the hunger marchers; twisting of facts; fabrication of “facts” out of whole cloth; suppression of important events, particularly the provocative actions of police in Washington and elsewhere; these are among the crimes committed by the capitalist press in what was nothing less than a deliberate and sustained press campaign against the hunger march. The alliance of the press with the government and the capitalist class, in the attempt to suppress the hunger march and its demands, could scarcely have been closer if the capitalist press were openly a part of the state apparatus.

The very nature of the hunger march was twisted. The marchers were delegates elected by unemployed councils, trade union locals, and other bodies; they were delegates, elected representatives; but the newspapers and the press services suppressed this fact and on numerous occasions referred to the 3,000 delegates as if this number were the entire strength of the organized unemployed and employed in this country fighting for unemployment relief and insurance. Thus, the Associated Press was at pains to point out that the marchers were several thousand less than those in the bonus army, and built up a false picture of a hostile populace by dispatches, as that from Cleveland, November 30, that the marchers “made themselves uninvited guests of more Ohio cities today.”

Logic was thrown to the winds as the press, endeavoring to reach two different kinds of prejudices, attempted to portray the marchers as both prosperous (supplied no doubt with Moscow gold) and yet an unkempt, ragged lot. A typical example of this contradiction is the New York Times story of November 20:

“Most of the marchers did not appear either particularly hungry or destitute. They seemed warmly clad, with stout shoes and heavy coats. Many of the women wore fur coats.”

Yet the same story refers throughout to the “ragged army”! The ultra-reactionary papers were usually more consistent, contenting themselves with arousing snobbery; the New York Herald Tribune’s references to “unkempt marchers” and their “tatterdemalion leaders” exemplify this tactic.

The stock device of quoting unnamed persons and thus injecting indefensible propaganda into news columns was used regularly. An example is the widely printed United Press dispatch of November 30 which invents the following accusation and the worse denial:

“Members of the radical squad here alleged that the marchers were receiving $1 a day during the trek. Denying this, a New England delegate insisted:

‘Lots of our fellows quit their jobs to go on the hunger march’.”

There were even attempts to use the splendid discipline of the marchers as an argument against them: as in the Washington Star of December 5:

“This appears to be an organized rigidly disciplined movement. No man expresses himself. The provost guard stops him if he tries to. It is another touch to the un-Americanism of the whole picture. Americans are babblers. Only in a European pattern will men give up free speech and let a provost guard put clamps on their tongues.”

The Star is apparently not averse to acting as a stool-pigeon; its staff correspondent, William W. Chance, got himself elected as a hunger march delegate in Uniontown, Pa. and wrote some particularly incitatory stories; and the Star thought so well of such contemptible tactics that it published a picture of Chance’s credentials as a hunger march delegate. The Star’s attitude has more than local significance, since its owner, Frank Noyes, is also president of the Associated Press.

First, then, the press built up a false picture of the marchers’ character and plight. Then came much more dangerous stuff. As the marchers neared Washington the press carried stories describing them as disorderly and riotous.

The Western column stayed overnight at Cumberland, Maryland, where they were confronted by an enormous crowd of police and armed citizens, including half grown boys armed with guns and clubs. But the marchers had no trouble; they stayed overnight on a sympathizer’s farm and left the next morning. The camp at the farm was orderly and quiet. Yet the New York Times carried a story with these headlines: “Ousted Marchers Riot in Maryland.” “Herded at Farm by Cumberland Citizen Army, 1300 Start Battle for Release.” The Associated Press carried a similar story saying that “the men encamped there were fighting among themselves.” On the basis of this story, the New York American ran an eight column streamer, “Hunger Marchers in Riotous Mood as Vanguard Draws Near Washington.” The Associated Press’ authority for the facts was the Cumberland Chief of Police. None of the Washington papers carried this story: the most even the bourbon Washington Post could do with it was to say that “Cumberland Guns Avert Crisis.” The New York Times and Associated Press’ stories were complete fabrications.

All the Bunk That’s Fit to Print

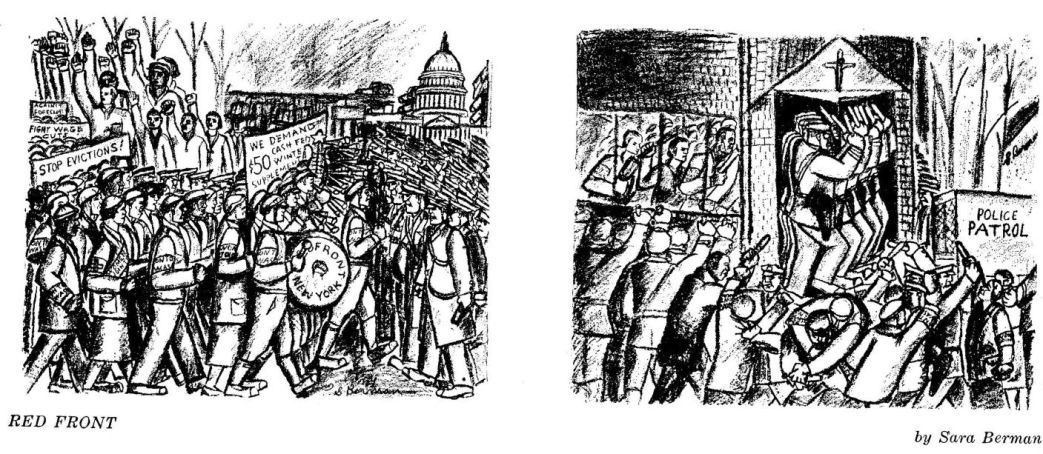

In Wilmington, Delaware, a group of marchers from the Eastern column attempted to hold an outdoor meeting in front of the church in which they were quartered; the police broke up the meeting, drove the marchers into the church, locked them in then broke the windows and filled the church with tear gas. The New York Herald-Tribune and Associated Press’ euphemistic way of referring to this police attack was to say there was “an outbreak at an old church.”

By such fabrications a picture was built up in the press of a riotous disorderly mob converging on Washington. The worst offenders in this tactic were the Associated Press and the New York Daily News. An A.P. Washington dispatch of December 3, said:

“A national capital fully prepared for all emergencies listened in tense silence tonight to a threat of ‘forcible action’ voiced by leaders of demonstrators approaching the city…

“Herbert Benjamin, one of the sponsors of the march, said such a course would be followed, if necessary, to overcome superior police force.” (My emphasis).

No place and time for this alleged statement is indicated, which makes it more difficult to convict the Associated Press in court for libel.

The New York Sunday News of December 4 actually went so far as to invent a complete speech by Benjamin and report it as having been made in Tom Mooney Hall, Baltimore, the night of December 3. This fabrication appeared under the headline, “Reds Threaten Bloodshed on Capital March.” Benjamin was quoted as saying:

“‘They kept us out last year but Monday we’ll break into the Capitol by brute force!’ the agitator declared…’They’ll listen to our demands or we’ll stage a riot right on the spot!’

“’The cops can’t put us out—there aren’t enough of them. If Hoover brings in the troops there’ll be a massacre. Pennsylvania Ave. will run red with blood’.”

There was no meeting in Tom Mooney Hall that night. Benjamin spoke at a meeting in the Baltimore Armory and said none of the things he is reported to have said, as I can personally testify. He spoke at 11 p.m.; and the News which quotes him was already on the streets of New York at that time!

The press as a whole, therefore, had given its help in picturing the marchers as a riotous mob bent on bloodshed; this picture certainly helped prepare the country for bloodshed in Washington.

The Provocations of the Press

Nor did this campaign of justifying provocation end at the outskirts of Washington. The creation of the detention camp on New York Avenue, isolating the marchers, facilitated the provocation scheme of the government. The flimsy excuse of the authorities for isolating the marchers was that no accommodations were available for them in the city. The city of Washington is full of empty warehouses, halls, buildings; if the Unemployed Councils did not have sufficient funds to rent them, friends of the marchers were ready to put up the money. But, strangely enough, owners of the empty buildings, who are losing their buildings because they cannot pay taxes, refused to rent them to the marchers. Can anyone doubt that this was due to the instigation, the intimidation, of the Federal authorities? Yet the Washington newspapers published the preposterous excuse of the authorities for detaining the marchers, without question, the Post and Star justifying it editorially; while the New York newspapers either reported the failure of the marchers to secure housing as a simple fact, or took the detention camp as a perfectly justifiable procedure. The newspapers even suppressed the fact that, though there was room for 1,000 marchers in the homes of sympathizers, the marchers were not permitted to go to them.

The campaign of justifying provocation continued, but with a significant difference between what appeared in the Washington newspapers and what was written for the rest of the country. In the Washington press there were general, vague references imputing a disorderly attitude to the marchers; as in the Washington Post editorial of December 6th, which spoke of “the ugly temper of the horde of vagrants”; speeches were always referred to as “inflammatory speeches” which “aroused the marchers to fanaticism”; but since the marchers made no overt act which could be misinterpreted as disorderly, the Washington newspapers had to be content with such editorial phraseology for coloring the news columns. The Washington newspapers could not be so completely crude as to invent events which did not take place, since in Washington itself this could be quickly checked up. But the correspondents writing stuff for consumption outside Washington had a freer hand. I shall content myself with two significant examples of fabrication by the press services and the New York newspapers.

As soon as the marchers arrived on Sunday and were penned in on New York Avenue extension, they set up picket lines to keep marchers from straying anywhere near the police. Not even the most reactionary Washington newspaper did more with this situation than refer to the picket line and its cry of “Back, Comrades, Back.” What, however, did outside papers do? I quote an A.P. dispatch in the December 5 New York American under the heading, “Rush Frustrated.”

“An attempt by a number of the demonstrators to rush the police lines was frustrated without violence by their leaders.”

And the Herald Tribune, December 5, reported:

“A column six abreast, swept down suddenly on the police in the dark shouting, ‘Get by the lines!’”

This “attempt to break past the guard” happened only in the minds of the Herald-Tribune and Associated Press correspondents.

Similarly with Monday afternoon’s rehearsal for Tuesday’s parade. Vicious as the Washington papers were they could not twist this into an attempt to clash with police. But papers outside of Washington could. The A.P. dispatch said:

“Fretting and fuming under police restraint, the throng at one time drew up in marching order, raised a huge red banner and headed straight for the solid lines of police.

“But when the blue ranks tightened to meet them, the leaders turned aside and jeered the police f or their precaution.”

And over this story the New York World-Telegram put the head, “Hunger Army Moves on Cops, Then Retreats.”

Proletarian Discipline

Thus far the capitalist press attempted to picture the marchers as a disorderly mob. But by Monday evening it became clear to the most biased observer that the disorderly mob in Washington was the police. Affidavits from John Herrman, Slater Brown, Mary Heaton Vorse, Malcolm Cowley, Michael Blankfort, Edward Dahlberg and other writers who covered the hunger march, testify to the brazen attempts of the Washington police to provoke disorder. In addition there are the reports of December 5 and 6 in the Washington Daily News, the one honorable exception to the dishonorable silence of the press. Particularly on Monday night, December 5, drunken, murderous cops slashed automobile tires, tore banners off trucks, spat at the insulted women, and yelled at the marchers: “Come on you yellow bastards! Try and break through!” Yet, despite the fact that every newspaper and press service had representatives present who saw these events, the Washington Daily News was the only newspaper to expose the situation. And though the Washington News is a Scripps-Howard newspaper, we may safely assume that it is not the Scripps Howard organization that is to be thanked for that honorable example; for the New York World-Telegram suppressed the story in toto. The only other paper which even referred to police provocation was the New York Times—which buried the story on page 46! No other paper in New York or Washington, and none of the press services carried a line.

In other words the press had attempted to picture the marchers as a disorderly mob; but when the disorderly mob turned out to be the Washington police, the press suppressed the whole story.

The provocative tactics of the Federal government failed, thanks to the most extraordinary exhibition of discipline by the marchers; with no pretext for driving the marchers out and an avalanche of protests against the treatment accorded them, they finally had the pleasure of seeing the Federal authorities back down; they had their parade and petitioned Congress on schedule, Tuesday. The schedule also called for the astern columns to leave Tuesday night and the western to leave Wednesday morning; long before this the schedule had been printed by the newspapers themselves. Yet, in a deliberate attempt by the press to minimize the victory of the hunger marchers, the newspaper stories stated that the marchers were permitted to parade in return for their promise to leave Washington. The Washington Herald ran a headline “Permission Won by Pledge to Disband and Leave D.C.” A United Press dispatch of December 6 in the New York World-Telegram read:

“In return for the privilege of marching on the Capitol the leaders of the ragged group agreed to disband tonight and start on the back trail toward home”

An Associated Press dispatch of December 7 in the New York Herald Tribune:

“Under persuasion of police all but a few of the self-styled hunger marchers left the capital today.”

Some of the attempts to minimize the parade were absurdly crude, such as the Washington Herald headline, “Parade a Flop to Big Crowd” over a signed story by James Cullinane which said nothing of the sort. The big point of the New York Herald-Tribune and World-Telegram stories was that “Curtis Silences Hunger Parade Leaders Slur.”

Before the press eagerly dropped the hunger march from its columns, one other story appeared, in Associated Press and United Press dispatches as well as in the Washington press, to the effect that large supplies of food had been left behind by the hunger marchers. John Herrman sends word of the actual facts: This food belonged to a group of veterans who had been penned in with the hunger marchers, but who intended to stay in Washington to demonstrate for the bonus. After the hunger marchers left, the police drove the bonus marchers out of town on foot, giving them no opportunity to take the food along or to store it anywhere. Then the police rolled the food down the embankment and turned it over to the railroad detectives for distribution—first having had the press take some pictures. John writes that he saw this, confronted the United Press ana Associated Press correspondents with the facts, and that they promised to write retractions just as long as the original stories. The retractions have not appeared; nor do I expect any retractions of any of the misinterpretations and fabrications indulged in by the press, a few samples of which I have listed. It is, indeed, in the old, vivid phrase, the kept press.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1933/v08n06-jan-1933-New-Masses.pdf