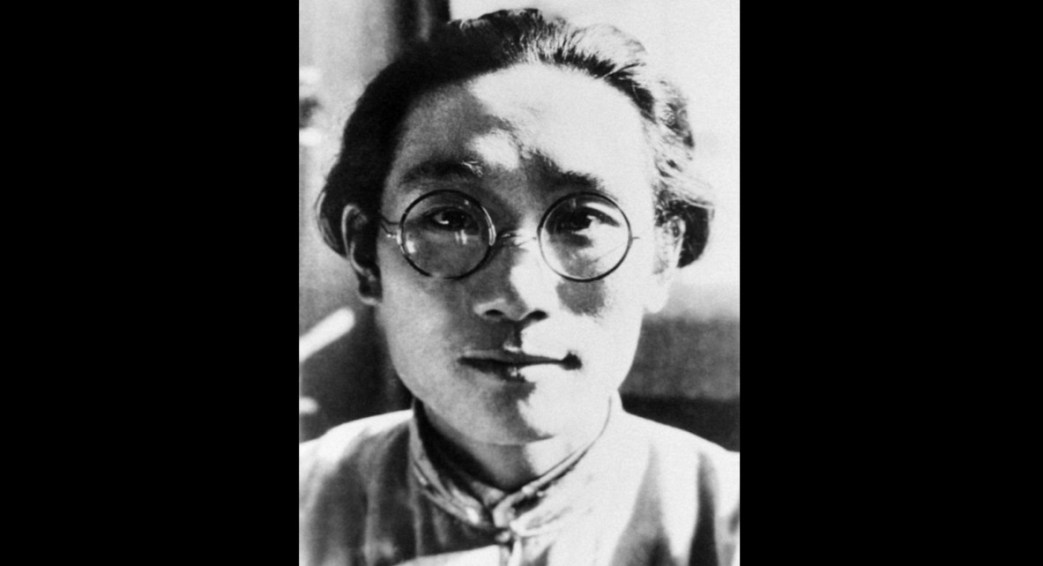

Rou Shi (Lu-Tsche-Sing) was a central figure in the League of Left Writers, and one of its Five Martyrs to be executed by the KMT along with dozens of other Communists on February 7 1931. The report on what would soon be dismissed as a ‘ultra-left’, along with the Li Lisan leadership of the Chinese Communist Party, would–in the future–not be considered the first meeting of the Chinese Soviets, rather congress called by Mao and held in November, 1931 would hold that title.

‘At the First Conference of the Chinese Soviets’ by Lu-Tche-Sing from Literature of the World Revolution, No. 3. 1931.

The short account, published below, by the young Chinese Communist writer. comrade Lu-Tche-Sing, gives a sketch of the conditions under which the first conference of the representatives of the soviet districts of China took place, at. the end of May, 1930. At the conference there were present, besides representatives of the soviet provinces Tzyan-si, Hube-yi, Hu-nan, Fu-tzyan, Gu-an-dun, Cuansi, and likewise of the Chinese Red Army, of the Red and Youth Guards, representatives of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, representatives of the Red trade-unions and other revolutionary organizations: in all, forty eight delegates.

Soviet China has its roots in the revolution of 1925—27, and first took form concretely in the famous Hai-lu-Fyn Red Republic (November 1927-end of February 1928) and in the heroic Canton Commune (11-13 December, 1927). At the beginning of 1930 it included extensive districts of the southern provinces, hundreds of counties, in area and population representing a wide-sweeping country with tens of millions of inhabitants. Each soviet district, gripped by the enemy’s encirclement, engaged in fierce struggle for its existence, had to settle a whole series of extremely complex social, economic and political problems. Among the different corps of the Red Army, as well as among the various soviet districts sufficient contact had not yet been established at the time of calling the conference, and the Chinese Communist Party was not always able to cope with the task of leading the entire soviet movement.

The first conference of the soviet districts of China was summoned in order to take advantage of the enormous revolutionary experience of the various soviet districts, in order to take a decisive step toward unifying the separate parts of the Red Army into a single All-China Red Army, in order to strengthen even further the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party, to outline the Bolshevik way of solving all the burning questions brought forward by the very course of the revolutionary struggle and, finally, in order to make ready for the All-Chinese Congress of Soviets.

Comrade Chao-yu-Shi, whose pen name is Lu-Tche was one of the founders of “The League of Chinese Left Writers.” He was on the presidium of the League and its bureau and in addition was the manager of the editorial department. In May 1930 he represented the League at the first conference of Chinese Soviets. The sketch published below was written after the conference.

On Jan. 7th he was arrested by the English police who handed him over to the Chinese authorities. On the evening of February 7th he was shot.

Among the writings of comrade Lu-Tche may be mentioned: 2 books of short stories entitled The Madman and Hope; a novel, The Death of the Old Epoch; a drama in verse, The Three Sisters. He also made many translations from other languages. He left a number of unfinished works, of which several, including The Pioneer, were confiscated when he was arrested.

***

The Conference worked through a tremendous lot of tasks, summarized in the resolution on the contemporary revolutionary movement and on the political tasks of the soviet districts, in the temporary law on land, in laws for the protection of labor, for the emancipation of women, for the introduction of the graduated income tax, finally in the resolution in defense of the U.S.S.R. and the manifesto for summoning the First All-Chinese Congress of Soviets.

The work of the Conference was carried on in the secrecy of underground methods. The political gendarmerie, the police and counter-revolutionary espionage had all been set going by Nankin. But all the efforts of the bloodhounds of the Kuomintang turned out to be useless. They did not succeed in arresting a single delegate—and that would have meant cruel torture and death.

Certain theses and decisions of the Conference have since been subjected to justified criticism (and were corrected in time). Nevertheless, no one denies its services and its historical importance.

Then, comrades, come rally and the last fight let us face.

The International unites the human race.

We have just done singing the great, heroic hymn. There are forty-eight of us. We are standing–in close ranks in deep silence. Our attitude is calm and determined. Only our arms are relaxed and our heads slightly bent forward. Our mood is exalted, militant. The sounds of the hymn, like a splendid cloudlike ship, bear us away under the red sail of communism to a happy country in which classes are no more, in which is only equality and freedom.

There are forty eight of us. We are seated in a spacious room at tables arranged in the form of the letter I. The tables are decked with red cloth, and fresh flowers stand on them. In the electrical atmosphere, between the walls as red as fire, the conference is opened.

“Comrades! Throughout the land the red banner of the Soviets is being raised on high.” The deep, calm voice of our president resounds.

We are all brothers, and our organization is like a family. Our speeches, conversations, our comings and goings, all our movements and actions are regulated according to the strict rule of conspirative work. Among us is one girl: “Comrade-sister.” All material cares are placed on her. She is well-built, beautiful, kindly. Every evening, before going to bed, she wishes us all a “Good night.” During the long sessions we often hear her gay voice: “Who wants zhen-dan?”

In order not to make any noise with our chairs and benches, we have our dinner standing up, like soldiers. One comrade standing at the table, waiting for dinner, remarked in his hunger:

‘‘Our way of dining reminds me of a battle. Our chopsticks are bayonets, the rice is like bullets, the fish and meat are the cowardly enemy. Why doesn’t he put in an appearance? We are roaring to go!”’

After supper, if there is no session, we carry on quiet but lively conversations and discussions. The delegates become better acquainted with each other. Each one shares his revolutionary experience and questions the others.

‘‘What organization is that comrade from?” You hear this question continually.

The delegates coming from the different soviet districts and the Red Army divisions are especially anxious to learn how matters stand in Shanghai at present.

“Well, how about it, are the Shanghai workers, artisans, poor people thinking about the revolution? Are they making haste? Do they understand?” I am flooded with questions.

Evidently my answers do not entirely satisfy them.

“But Shanghai is important, very important,” they heave a sigh. “In the villages the revolution is growing and spreading with every day. Shanghai must come forward.”

It is difficult to deliver the Shanghai newspapers in the soviet districts. Thus, the present Fourth Corps of the Red Army for three weeks did not receive a single newspaper in its mountain fastnesses. They all began to get worried. The espionage service soon succeeded in learning that in such and such a place in such and such a city a few copies had arrived. That same night a regiment was dispatched. Having traversed sixty li (about thirty kilometers) the regiment burst into the city, seized the newspapers in the place mentioned and returned. That was a real exploit.

In the room where the session is being held, in one of its corners stands a table with books. The table drawer is stuffed with every possible left magazine, and with communist newspapers and books. A comrade especially appointed for that hands out and takes back the literature.

From early morning, when they begin to be distributed, every delegate, except for three or four illiterate peasant delegates, has a book, newspaper, or magazine. They read with great concentration. From time to time, when they come upon doubtful passages, they consult each other. They remind one of small schoolboys before an examination.

The illiterate comrades often come up to the ones reading.

“What sort of book is that?” a peasant delegate asks me.

“It’s a monthly magazine, We means I.”

“One of ours or not?”

“Ours. About proletarian culture,” I answer and relate the contents of the issue.

“Yes, that’s our journal,” the peasant smiles in a friendly way at me, and agrees

Thanks to our “comrade-sister” each of us has a notebook and pencil in his hand. During the session several write very energetically. In their spare time they draw.

“Our president,” “Our delegate from Guan-dun,” “Our splendid comrade-sister,”—I read these titles on extraordinarily finely done drawings in the book of one Red Army man.

They often ask me how to write this word or another.

“Break through the enemy’s line—is that the way to write the sign ‘break through’?” And in ‘sacrifice their lives’ how do you write the sign, ‘sacrifice’?”

One delegate put me in a quandary. I couldn’t understand the meaning of the hieroglyph he had written. It turned out he had invented it himself.

In answering the questions put to me I see whole pages filled with revolutionary slogans: “Let’s take the cities by storm,” “Bend all our ee to strengthening the Red Army and the Youth Guard,” and many others.

Beside me on the floor a comrade from Mukden sleeps. He is enormously tall, but his face is uncommonly kind. The first time I got into conversation with him, he told me about his revolutionary past. Although the son of a big landowner, he joined in with the “common people” and dreamed of overthrowing the autocracy of the “class of officials.” Taking only a gun with him, he ran away from home to join the bandits, whom he regarded at that time as the only enemies of the official class. He took part in many engagements. He was wounded more than once. One bullet went through his shoulder. Another wounded him in the neck, and even now he bears the scar just below his ear, as large as a silver dollar. He soon realised that banditry wouldn’t lead to anything, that the entire feudal order must be overthrown, and he entered the revolutionary proletarian organization.

“In the last five or six years I’ve had to be about everywhere. When I was leading an engagement…”

My neighbor did not succeed in finishing. The voice of our watch on duty was heard.

“Eleven o’clock. Put out the light. No more talking.”

The following day I receive a note from my Mukden comrade.

“Is there such a thing as love?”

I am rather puzzled by such an unexpected question, but nevertheless I write an answer: “What sort of love? Love is of different kinds. Love too depends upon class.”

“Not that, that’s not it,” he shakes his head. “I wanted to ask how to suppress this feeling in myself.”

The comrades from the soviet districts relate how in the beginning most of the peasants were decidedly opposed to freedom of love and divorce.

Here is a typical example!

A young communist fell in love with a married peasant woman. She announced her desire to get a divorce. The husband, frightfully angered, began at the meeting to complain to his fellow-villagers. “Revolution! Revolution! But when it comes down to it, they simply want to take our women away.”

The peasants became furious and right then and there began to talk about handing out rough justice to the young communist. The party organization had to send him off to work in another place.

Quite another situation among the peasant-women. They demand their freedom and often make declarations of divorce. The civil authorities in the soviet districts are swamped with divorce cases. If the soviet refuses to grant the divorce, the women make speeches at the village meetings and defend their rights from the tribune.

Lately, the soviets have granted complete freedom of divorce and at the same time are carrying on suitable propaganda among the peasants. In many places the situation of the women has. already improved very much.

In the Red Army the men do not look with approval on love affairs. That is explained by the fact that there are still very few women soldiers in the Red Army. Moreover, they are usually not indifferent to the Red commanders. It is true, in the Red Army everyone is equal both in a material sense and in discipline, but some occupy more responsible posts and others less so. Among women, even in the Red Army, vanity plays its role. And that is why some corps commanders, to avoid all complications, do not admit women to their corps.

Among the delegates to the conference stands out an energetic young man, sixteen years old, a little uncouth in appearance, with a dark-colored but extremely good-hearted face, with round, shining eyes. Splendidly built, broad-shouldered, with powerful, muscular limbs he seems to me to personify the strength of the revolution. He is in command of one of the detachments of the Young Guard. He spent in all two years in primary school, but he is already able to write poetry. He read one of his compositions to me.

“Better devote yourself to the revolution, and give up writing love lyrics,” I advise him.

He laughs: “I’m not an expert in this, I took this from one collection. But aren’t there poets among you revolutionaries?”

“If we could teach this lad for two years in Shanghai,” our president remarked to us, “he would turn into a fine Young Communist leader. Only we can’t leave him in Shanghai. Such lads are needed in their own districts and indeed everywhere.”

While talking to one elegantly dressed comrade, a young commander drew his attention to a bright-colored silk kerchief sticking out of his side-pocket. He took the kerchief up and began to examine it very carefully.

“What sort of thing is that?”

“Nothing much. Just for looks. If you want it, take it along. When you go back, you can make a present of it to your sweetheart.”

The commander carefully folded the kerchief and put it away.

“Down with militarism.”

“Down with imperialism.”

“Strengthen the Red Army with all our forces.”

“Prepare the uprisings.”

“Long live the victorious Chinese revolution.”

“Long live the world revolution.”

With these martial slogans our conference came to an end. We all joined in, raising our hands together. But behind each of us stood the tremendous shadow of thousands and millions of toilers. These were their mighty voices. That was their exultation.

With blazing torches in iron hands we will go to the masses of workers and peasants. Arise, China! Perhaps you are destined to light the world conflagration.

Literature of the World Revolution/International Literature was the journal of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers, founded in 1927, that began publishing in the aftermath of 1931’s international conference of revolutionary writers held in Kharkov, Ukraine. Produced in Moscow in Russian, German, English, and French, the name changed to International Literature in 1932. In 1935 and the Popular Front, the Writers for the Defense of Culture became the sponsoring organization. It published until 1945 and hosted the most important Communist writers and critics of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/literature/international-literature/1931-n03-LWR.pdf