In Italy, as elsewhere, Fascism’s ‘strengths’ are only strengths in relation to the opposition’s divisions and weaknesses. A fascinating look at the precarious economic and political situations of a victorious Fascism as Mussolini’s regime gained total control of all institutional powers and moved to conclude an agreement with the Roman Catholic Church. The prolific, multi-lingual Peluso, once a member of the Socialist Party of America in the early 1900s, joined the Italian Communist Party in 1921. He would move to the Soviet Union in 1927 where he joined the Russian party and taught Italian labor history. A victim of the Purges, he was arrested in 1938 and executed on January 31, 1942 at sixty.

‘The Position of Italian Fascism around the Turn of 1928 and 1929’ by Edmondo Peluso from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 9 No. 5. January 25, 1929.

We must not allow ourselves to be deceived by the apparent calm prevailing in Fascist Italy. It is the outcome of an unprecedented system of oppression employed against the working masses by means of an apparatus of coercion which can hardly be equaled elsewhere. But beneath the surface a volcano is seething and finds expression from time to time in spontaneous eruptions of proletarian hatred (strikes, disturbances, the murder of Fascists, etc.); these are naturally put down at once, but they are yet characteristic symptoms of the true situation of Fascism at the present moment.

Fascism has entered upon an extraordinarily serious crisis, which is bound to be aggravated as time goes on, especially when the financial obligations the Government has incurred, fall due. All the economic “battles” which Mussolini undertook to fight with vaunting words and gestures, have been lost. The economic position of Italy in general and the financial position of the State in particular give proof of this fact. It must be admitted that the State balance-sheets submitted by ex-Minister of Finance Count Volpi, were forged.

The Government balance for the year 1927/28 closed with a deficit indicated at 1,356,000,000 lire but in reality amounting to nearly 2000 millions. In spite of the coercive measures of the tax authorities, in spite of the elaboration of the bureaucratic apparatus, in spite of the taxation of foodstuffs and commodities such as bread and tobacco, and in spite of the fact that the tax on salt has been trebled, the Government revenue is constantly on the decline, by about 100 million lire monthly. By the end of June 1929, the deficit of the first half year will presumably already exceed that of the entire year 1928. The costs of the bureaucratic apparatus of oppression and of the Fascist service of espionage are continually increasing. Exports continue to decline. The surplus of imports over exports, which in the first nine months of the year 1927 amounted to 4278 million lire, figured in the first nine months of 1928 at 5749 millions. The data for October show that this deficit was increased by another 787 millions in that month. This adverse balance of trade is aggravated by the change in the character of imports. Italy imports fewer and fewer raw materials or semi-finished goods, while the quantity of industrial commodities constantly grows. This is an indirect admission of the catastrophic situation of Italian agriculture.

Savings, too, grow smaller and smaller. The reason is obvious. Want draws ever wider circles among the population. The comparatively small number of savers have lost confidence in Fascism. The gold of the Italian proletarian emigrants, which for the last forty years has figured as a very important asset in the Italian banks, is now almost wholly lost to them, since the emigrants now generally deposit their savings with American banks. Italian emigration, moreover, has declined by about 80 per cent. during the last few years by reason of the immigration restrictions in America and of the smaller call for foreign workers in France and other countries.

What, meanwhile, is the position of Italian industry? The revalorisation of the lira entailed the loss of a certain number of markets and the depression of agriculture. The attempt to reconquer these markets with the help of rationalisation or, to put it more plainly, by a reduction of wages and by a concentration of capital, was doomed to fail. The appreciation and stabilisation of the lira itself could only be attained with the aid of foreign capital. The United States alone furnished some 12,000 millions and thus secured the control and a considerable encumbrance of a certain portion of Italy’s industry. The increase in the productive capacity ought to have been accompanied by an extension of the inner and outer markets. This was not the case. The impoverished Italian masses have a smaller purchasing capacity than ever before. Therefore, certain industries, such as the textile industry and the automobile industry, seek to force exportation by granting their customers long-termed credit, in consequence of which they themselves constantly suffer from a dearth of capital. The result is a scarcity of money which entails a great general depression throughout the country and so many bankruptcies that the Government has determined only to declare such firms bankrupt as desire it themselves. (Circular of Minister of Justice Rocco.)

Unemployment increases rapidly. Although the Fascist Government officially indicates no more than 515,000 unemployed, the actual total exceeds a million.

Is there then any possibility for Italian industry to acquire new credits? Wall Street does not seem to be inclined to grant them. In consequence, the Italian bourgeoisie is commencing to offer that portion of Italian industry which is still in its hands for sale on the foreign stock exchanges. The lead in this direction has been made by the great Italian chemical trust of Montecatini. And German capital, in the form of the I.G. Farben, is already stretching out its tentacles towards this greatest of Italian industrial trusts.

According to this programme, Italian industry is becoming more and more the vassal of foreign capital. Hence the great contrast between Italy’s foreign policy, which is that of a great imperialist Power, and its economic policy, which has lost practically all independence. Altogether, the decay of the entire economy is advancing with giant strides. Not only do the middle-sized enterprises disappear; even those of the heavy-metal industries, such as the Ilva, are threatened. One bank failure follows on the other; the concerns in question are mainly provincial banks, which have managed by fraud to ap propriate the last penny of many an Italian farmer.

In the opinion of the general public the Fascist State appears in the light of a fraudulent business-adventurer out to steal their savings. Since the Government cannot pay back the short-termed loans, it has arbitrarily consolidated them. For the purpose of procuring 200 million lire which were badly needed, Treasury bills were issued which were secured on deposits in the post-office savings bank and on bail in the hands of the Government.

After the catastrophic results of the last few loans, to which all and every, even such as provedly had no money at all, were obliged to subscribe, any new loan is destined in advance to be a failure. Today, two years after the issue of the last loan, the Italian State has not yet emitted the relative title-deeds. Now pressure is being brought to bear upon the subscribers to persuade them voluntarily to relinquish their claim to title-deeds as a sacrifice on the altar of the Fascist State.

The “industrial battle” is lost. So is the celebrated “grain battle”, which engendered the strangest results, inasmuch as grain production, which had figured at a value of 65 million lire in 1925, receded in 1926 to 60 million lire, and in 1927 to 53 millions. In the year 1928 it recovered very slightly. The other agricultural products, oats, rice, wine, oil, etc., have regressed in a similar measure.

The Fascist taxation policy, which altogether favours the big landowners, has completely ruined the middle peasants, once the most enthusiastic supporters of Fascism, but now its bitterest opponents. Added to this, hundreds of thousands of day-labourers now form a revolutionary mass. From time to time their discontent has found vent in acts of violence, as recently at Pordone (Ventia) and Molinella (Emilia). But a cruel and immediate suppression of the disturbances always restores “order”.

Unemployment in the rural districts never attained such dimensions as it has at present. There are provinces, such as Ferrara, in which 80 per cent. and more of the workers are unemployed. The peasants can emigrate neither abroad nor to the cities. Mussolini recently issued a decree forbidding the inhabitants of rural districts to leave their own villages without a permit from the authorities. Every village thus becomes prison, which starvation may tomorrow turn into a hotbed of revolution.

Fascism fully comprehends this danger and has again promulgated a plan which is calculated to provide work for the unemployed, namely that of a general improvement of the untilled ground. This “magnificent plan” is based on an expenditure of 7,000 million lire, distributed over 15 years and payable by the tax-payers. But countless difficulties lie in the way of its realisation. In the meantime the hunger of the unemployed increases. Therefore Mussolini and his Ministers have now resolved to make do with 270 million lire, so as immediately to appease the thousands of agricultural workers, whose ranks are swollen daily by more and more unemployed workers from the towns. Fascism seeks refuge in “national workshops”, similar to those which existed in France prior to 1848. But these naturally by no means suffice to provide work for the masses of unemployed.

In the meantime the indignation of the unemployed agricultural workers rises from day to day. Many roam about as vagabonds in search of bread. Such communities as are obliged to support them get deeper and deeper into debt. Ex-Minister of Finance De Stefani has announced that the indebtedness of the provincial capitals has advanced from 3066 millions in 1925 to 5481 millions in 1928. Meanwhile the Fascist leaders, who are under no control, rob the State Treasury at will.

Thus not only the industrial but also the agrarian plan has miscarried, Can Fascism therefore be said to have succeeded in establishing itself politically?

True, Fascism has arrived at the extremes of political stabilisation. All is Fascisised, the State apparatus, industry, commerce, the schools, the trade unions. But this is only on the outside, for in reality all, save the landowners, the interested capitalist groups, and the high functionaries of the Party, are anti-Fascists. The social basis of Fascism, which in the moment of victory and for a short time afterwards was very broad, has shrunk to the narrowest dimensions. The socially most important element of the petty-bourgeoisie in town and country has quitted Fascism or is about to do so. The entire proletariat, both urban and rural, is opposed to Fascism.

Nevertheless, there is apparently no opposition in Italy, the hegemony of Fascism is undisputed, it has even destroyed the entire constitution. The Supreme Council and the Fascist Chamber of Corporations have taken the place of the “freely elected” organs of Government. The local administrative bodies are appointed and the workers controlled through their trade unions.

In reality, however, affairs are very different. Both the economic and the social basis on which the Fascists have erected their regime of fire and iron, are beginning to shake.

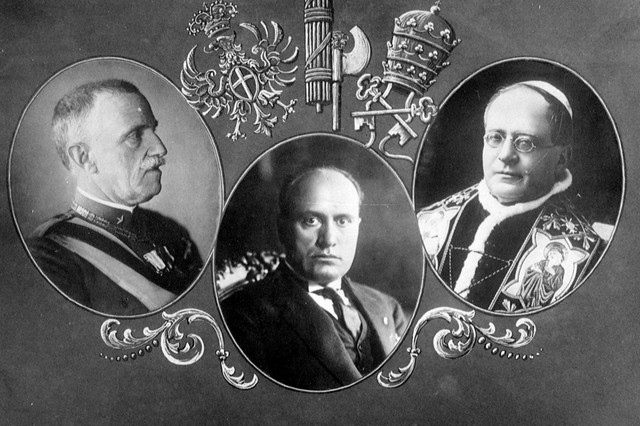

Added to this, a struggle is going on, albeit silently, between the Pope and Mussolini. That is why the Roman Catholic papers have been forbidden to occupy themselves with politics. Nevertheless, the influence of the church organisations has only increased. In the rural districts, most of the oppositional elements are grouped round such Roman Catholic organisations as still exist.

This dangerous position of Fascist Italy, which is internally decayed and outwardly isolated, and the dwindling support given to Fascism by the broad masses, have induced Mussolini once more to rally around him the “old Fascists”. i.e. the original Fascist cadres.

All Italian workers, whose position is wellnigh unbearable, abhor Fascism. They may be divided into three groups. One of these is altogether depressed and has lost all hope. Another is full of hope for the future, but considers the “powers that be” too strong and the present time inopportune for action, wherefore it elects to remain inactive. The third group is composed of the active elements who know that Fascism must absolutely be beaten and that it can only be beaten by force of arms. This group forms the vanguard endeavouring to banish lethargy and lead on the masses of the proletariat. It is the Communists who defy all tortures, executions, and indescribable persecutions in carrying on the struggle against Fascism. In this struggle they are now aided more and more by the fact that the very foundations of Fascism are increasingly undermined.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1929/v09n05-jan-25-1929-inprecor.pdf