A founder and central figure of 20s and 30s Czech Communism was Karl Kriebich (Kreibich) from a German-speaking Bohemian family. A country that came into existence out of the ashes of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, like nearly all of the new states that emerged after the war in the hope of winning national self-determination, Czecho-Slovakia was itself a denier of national rights.

‘The National Question in Czecho-Slovakia’ by Karl Kriebich from Communist International. Vol. 2 No. 4. July-August, 1924.

DURING the first two years of the existence of the Czecho-Slovak Republic, it seemed as though the only problem this new State would have to face would be the old question which had been the principal problem under the old dual monarchy, namely: the relations between the Czechs and the Germans. It soon transpired, however, that the new republic would have to face a far more important problem which, if it did not threaten the very existence of the State, would at least profoundly influence its direction. The problem is presented in the question: is Czecho-Slovakia a national State or a State of nationalities?

A National State or a State of Nationalities?

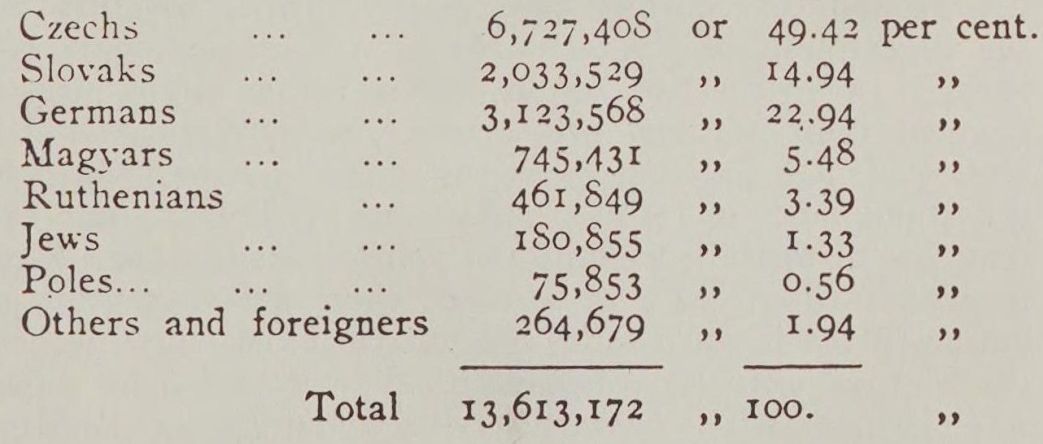

Light on this question is shed by the figures of the Census of 1921. At that time the national composition of the population of Czecho-Slovakia was as follows:

(Nationality was determined in this Census on the basis of individual declaration of national allegiance. The Jews were recognised as a nation; yet only one-half of those adhering to the Jewish faith (343,925) declared themselves as belonging to the Jewish nation. Czechs and Slovaks, as we shall see presently were classed as one nation; so there was no choice as between the two nations. I have separated them here by putting down as Slovaks the “Czechoslovaks” resident in Slovakia proper and in Carpathian Ruthenia. This assumption is even more favourable to the Czechs than the current pro-Czech estimate whereby one-fourth of the “Czechoslovaks” are given as Slovaks.)

From this table it follows that none of the nations and nationalities resident in Czecho-Slovakia represents a majority of the population. Czecho-Slovakia may, therefore, be considered as a State of nationalities in which, like Poland, no single nation is overwhelmingly in the majority. In order to create at least the fiction of a national State, another fiction was contrived: that the Czechs and the Slovaks are a single and homogenous nation. This was even carried to the extent of concocting a fictitious “Czechoslovakian” language, which does not exist at all. Thus, everything was done to create artificially a majority-nation or to use the expression of the national-imperialist vernacular, a State-nation and a State-language, in order to justify the existence of a Czecho-Slovakian national State. But even the State-nation so contrived embraces only 64,36 per cent. of the population, or less than two-thirds, so that even after the performance of the trick there are no grounds for speaking of a national State. It can only be maintained artificially, and by means of State coercion.

The Slovak Problem.

What are the essential features of the Czecho-Slovak question?

That the Czechs and the Slovaks ethnographically constitute one nation is a matter on which there can be no doubt; this was duly recorded by maps and statistics in numerous scientific publications of the pre-war period. The Czechs and the Slovaks were mostly heaped together under the description of “Czecho-Slavs.” The philologic differences between the two languages are rather slight: less pronounced than, for instance, between Swiss-German and low-German. But national questions should not be treated from the standpoint of ethnography and philology, but rather from the historical economic and political standpoint. Already in feudal times, i.e., at a time when the conception of a nation in the modern sense did not yet exist, the Czechs and the Slovaks were separated politically and ruled by different sets of rulers. The contact between them during the Hussite and Reformation period was too episodic to leave any lasting effects. Although since 1526, except for short intervals, the Czechs and the Slovaks were governed by the same dynasty, nevertheless, they remained politically separated; for even at the zenith of Habsburg centralism, Hungary constituted a separate political entity. The Czechs and the Slovaks had gone through the decisive economic development of the 18th and 19th centuries under two entirely different sets of economic circumstances. In the Austrian half of the Habsburg monarchy, the Czechs had been drawn into the stream of capitalist development. They produced a prosperous middle-class, a large and small peasantry, a bourgeoisie, an industrial mass-proletariat, as well as numerous classes of alert and ambitious intellectuals of all grades. The Slovaks remained under the sway of the economic and nationalistic policies of the dominant Magyar aristocracy—the latter-day landlords and capitalists—and this Magyar domination in Hungary was nationally more powerful and efficient than that of the “German” nobility and of the German bourgeoisie in Austria. The bulk of the Slovaks remained a poverty-stricken peasant people, for whom the only chance for advancement lay in emigration to America. It is true that, during the period of “national awakening” starting somewhere about the 20’s of the 19th century, there were numerous literary and political points of contact between the two nations; but on the Slovak side they were shared only by an infinitesimal group of intellectuals, leaving the rest of the people entirely unaffected. The Czech bourgeoisie took no interest in the poor Slovaks from whom nothing could be drawn; they considered Vienna, Chernowitz and Trieste to be more important places by far. On the other hand, the Czech agrarians were far more concerned with the competition of Hungarian grain than with the lot of the poor in the Slovak villages. The attempts of the Czech Social-Democrats to gain influence in the Slovak Labour movement met with no appreciable success, because the Magyar Social-Democrats, in league with trade unions, had so centralised and Magyarised the Party that the Slovak movement had become for them a mere appendage.

The Slovaks were even more surprised than the Czechs by the advent of national emancipation, and by the formation of the new State. The Czechs had at least carried on some national-revolutionary activity within the country (of course, illegally), and among the emigrants in foreign lands, whereas the only Slovak activity to speak of was conducted entirely abroad. The Slovaks in the Czecho-Slovak legions in Russia and the Slovaks in America (before the Revolution, more Slovak newspapers were published, and more Slovak national activity was carried on, in the United States of America than in Slovakia proper) were the only two factors in the cause of Slovak national emancipation, and the covenant for the formation of a joint Czecho-Slovak State was signed on the 30th of May, 1918, at Pittsburg, Pa. In that document there was as yet no talk of one Czecho-Slovak nation, nor the “Czecho-Slovak” language. On the contrary, provision was made for a separate parliament, for separate law courts and administration, and the promise of far-reaching autonomy for Slovakia was given.

The voluntary union into one common State corresponded fully to the degree of national and linguistic affinity which existed between the Czechs and the Slovaks, and it could be advantageous to both sides. Weak as separate units, the two nations would have been strengthened by this bond of union. By this union the Slovaks would gain culturally, because they would be brought nearer to the West, the walls of Magyar captivity would be demolished, the rich Czech literature, original as well as translated, would be brought within the reach of the Slovaks (the Slovak of average education reads the Czech quite freely), and the whole level of enlightenment would be raised. Furthermore, the new spirit of anti-clericalism that prevailed among the Czechs during the days of revolution (somewhat reminiscent of the times of Huss) could certainly have cleared the fetid atmosphere of the Roman Catholic domination in Slovakia. It may also be taken for granted that the common national, economic, political and cultural life in our modern fastmoving and fast-changing times would have brought the Czech’s and Slovaks together, nationally as well as linguistically, and would rapidly remove any of the effects the century-old separation may have had.

Such indeed were the things anticipated by Massaryk, Benes, Stefanik and all those who were active in the legions in Russia, and who signed the Pittsburg covenant. Of course, amid the trumpets of war and victory, amid the exuberance of sentiment and the enthusiasm of speechmaking, many things that lay in the dim future seemed present and close at hand. Nevertheless, all these anticipations were based on quite shallow petty-bourgeois ideology, whose spokesman failed even to foresee that the Czecho-Slovak State planned by them would turn out to be a capitalist and bourgeois State, dominated by the laws of capitalist economy and by the class-interests of the bourgeoisie.

To the Czech bourgeoisie, to Czech financial capital, the national emancipation was merely a means to render their economic domination secure against foreign competition, to protect the independence of the country in which they possessed the monopoly to exploit the masses, both as producers and as consumers. These motives were akin to those which moved the Polish, Serbian and Rumanian bourgeoisie, while the two last-named bourgeoisies were prompted by similar motives to seek to extend their respective territories of exploitation. Thus, while in addition the Habsburg empire was broken up politically (and that is the crux of the problem of Central Europe) a large economic domain was broken up that had gone through common capitalist development in the past. In order to secure the existence of the new Czech state as a capitalist country in a capitalist world, it was necessary to incorporate the industrial border districts in which the majority of the population were Germans. Thus, the Czech state was burdened with fully three million Germans, who were simply annexed, while the inclusion of the German industrial districts meant the absorption of German capital, a strong rival to Czech capital. In order to carry this out economically and politically, and with the greatest possible speed, in order to secure the monopoly of the Czech bourgeoisie (monopoly is indeed the chief item in the bourgeois conception of the State), a strong hand was needed, a strong and firm centralised regime, and to this end it was necessary by hook or by crook to create a “democratic” majority, i.e., a majority—or State-nation. The Czech bourgeoisie could not afford to wait until the prolonged coexistence of Czechs and Slovaks would weld them into one nation; the thing needed was immediate, a priori Czechoslovak nation. Dreamers like Massaryk, Benes and Stefanik, and the wise Czech and Slovak intellectuals of America, had a quick and rude awakening. Already at Versailles a different wind blew and the crude capitalistic realities at home (where the Czech bourgeoisie adapted itself to the revolution as it did to the former Habsburg monarchy) mocked the dreams of bourgeois politicians and ideologists like Massarvk and Benes, like Habermann and Klopa. The Pittsburg covenant was torn into shreds, and instead of Slovak autonomy came the centralism of Prague, far more rigid than the former centralism of Vienna or of Budapest. The Czechoslovak nation and the “Czechoslovak language” were created by decree.

In order to lend reality to the decreed phantom, a regime of relentless violence was instituted in Slovakia. To start with, Slovakia and the Slovaks are much more backward in comparison with the “historic” countries (as Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia used to be described by the Czech bourgeois professors of political history) and with the Czechs in general. Slovakia, in spite of its considerable natural wealth, is a poor and economically mismanaged country, which was severely shaken by the collapse of Hungarian economy, which had been more centralised than that of Austria. Slovakia lacks a sufficiently strong bourgeoisie; the peasantry is too poor and backward, and the intellectuals are too weak to enable it to become a “State-nation.” Of course, it never entered into the mind of the Czech bourgeoisie to succor the weaker brother; on the contrary, they took advantage of its weakness to subjugate it completely. A new Local Government Act was adopted, whereby the old Austrian and Hungarian local government bodies were either abolished entirely or virtually subordinated to the State bureaucracy. This has been carried out so far in Slovakia, which was promised “autonomy,” and to an extent to which the Government would never have dared to apply in the so-called “historic countries.” To give an idea of the working of this Act, it may be mentioned that the county councils in Slovakia, powerless as they are, have not the right to appoint their own chairman. This power is held by the representative of the Central Government, who also prepares the agenda. The government also has the right, which it uses, to appoint one-third of the Council, even after it is elected. The country was overrun by Czech officials and gendarmes, who were not chosen from among the best elements of the service (as a matter of fact, many of them were exiled to that country as a punishment) and who behaved as if they were in an occupied country. Troops were sent into Slovakia in such numbers that new barracks had to be erected. There are far more gendarmes, policemen and officials in Slovakia to-day than there used to be under the old Hungarian regime. In places where enough exiled Czech officials could not be procured, the worst and most brutal of the old Hungarian officials were retained. Many of these are of Slovak origin, who, under the old regime were rabid Magyar Chauvinists, and to-day are equally brutal in their zeal for Czechoslovakia. It is characteristic that the Prague government could not find any other to appoint to the posts of chiefs of police at Kassa (Kaschau) and Bratislava (Pressburg), the two principal cities of Slovakia, than two of the worst Habsburg creatures of the old Austrian political police of Prague, who have distinguished themselves in the past by ruthless persecution of the Czech national-revolutionary movement. The principal features of this regime was the complete absence of security of personal liberty and political rights. Taking advantage of the continuity law adopted when the Republic was founded according to which all the laws and regulations of the old regime were to remain in force until repealed, the bureaucrats in Slovakia applied a royal decree dating back to the 18th century to deprive the opposition parties of their right of assembly and of other political rights. Then, during the last municipal elections in Slovakia the authorities abrogated the general law of the Republic, which permits the holding of electoral meetings without special permits from the authorities, and this was done on the strength of a royal decree of 1848.

The greatest injustice occurs in the question of citizenship. In Slovakia the qualification for citizenship in the Czechoslovakian State is not residence or birth, but is acquired according to Hungarian law, upon the payment of taxes in the same community for five years. Whoever possesses this right in a region which forms part of the Czechoslovakian State, is a citizen of Czechoslovakia. Tens of thousands of people suddenly became aliens, or became uncertain of their citizenship, even though they may have been born in Slovakia, lived there for decades, and may never have lived anywhere else. The majority of workers never earned sufficient income to bring them into the scope of the state and local taxes; the State employees were exempt from such taxes, and many communities did not raise these taxes because they had sufficient revenue from other sources. All these people now cannot obtain citizenship rights in Slovakia and State rights in Czechoslovakia. How many workers could have saved up all their tax-certificates in the conditions prevailing during the war? Nevertheless, if one of these certificates were missed, all was lost. The practices of the Czechoslovakian authorities in this respect are much more stringent than those of the Hungarians. The community cannot decide in this matter; even if the community be willing to reinstate a citizen, it cannot do so against the veto of the State officials, who may arbitrarily withhold the right of citizenship without even citing any reasons therefor. Thousands of workers have absolutely no political rights and no legal protection. If they become restive, they are promptly deported and handed over to Horthy. If they are out of work, they get no unemployment benefits. But if one becomes a police spy, a social-patriotic agitator or any other kind of governmental creature, he promptly receives rights of citizenship.

To this must be added the economic policy pursued by Czech financial capital in Slovakia. The industries of Slovakia, although as yet undeveloped, were of importance to the economic life of the country, and their separation from the Hungarian economic sphere was a heavy blow to them. The Czech capitalists determined to ruin them completely. The Slovak industries were the first to be hit by the industrial retrenchment undertaken by Czech financial capital. Some factories have been idle for years; others are being gradually closed down. The greatest iron foundry in Slovakia, which employed three thousand men, was dismantled and the equipment sold to Hungary; the smoke stacks were pulled down. The results of the industrial stagnation, and partial destruction, coupled with the heavy burden of taxes, which on the average has increased to 14 times that of the pre-war burden, aggravated by all kinds of duties, imposts and monopolies, with a depreciation of money to one-seventh of the gold parity, drive the people to emigration as the only resort. The former stream of Slovak emigration from Hungary to America was revived from the Czechoslovak Republic after the “emancipation.” Since its establishment the Czechoslovak Republic has lost about two per cent. of its population through emigration, and the greater part comes from Slovakia.

Such is the policy of the Czech bourgeoisie and of the Czech social-patriots and agrarians in Slovakia. The political outcome of this policy is quite evident. The Slovaks are in a state of profound disappointment bordering on bitter resentment. In Slovakia there are about two million Slovaks, 140,000 Germans, 637,000 Magyars, 83,000 Ruthenians and 70,000 Jews; but the greatest and strongest resentment against the Prague regime is felt by the Slovaks. All the nations in Slovakia are on good terms with each other, there is hardly any national hatred worth speaking of; but of late years the Slovaks have developed a national hatred which is directed exclusively against the Czechs, for the simple reason that the Prague regime is Czech. The Slovak proletariat remains for the most part unaffected by this wave of nationalist sentiment; it has drawn but one conclusion from the workings of the bourgeois democratic regime: it has gone over to the Communist camp. On the other hand, the overwhelming part of the Slovak peasantry and petty-bourgeoisie has thrown itself into the arms of the Slovak clericals, who have kept the governmental majority and have inscribed upon their banner the slogan of autonomy and the fulfilment of the Pittsburg covenant.

This slogan does not imply, of course, that the Slovak clericals (who call themselves the “Slovak People’s Partys”) are sincerely out for autonomy; they merely use it as a tool to further their own ends. Their leader, Illinke, the priest, is a confirmed reactionary demagogue whose chief aim is to keep the masses of the Slovak peasants and petty-bourgeoisie in the state of reaction, and whose only worry ever since the revolution is the fact that at the head of the Czech “Hussite Republic” is a man who once “fought against Vienna and Rome” and who might bring about the separation of church from State, and the secularisation of the schools. Illinke vacillated from one side to the other, and has still failed to make up his mind whether to achieve his aims by the aid of Poland, where his colleague Jehlikca, has become the centre of Slovak reactionary irredentism, or by Hungary, whither the Horthy reaction lures him, or by the rulers of Czechoslovakia. As long as he sees no other possibilities, he will be ready to ally himself with Prague. If his bankrupt bank will be re-established with the aid of government funds, if the schools and the church will be left undisturbed, he will be content with any sham or bogus autonomy, or with no autonomy at all. This would be a none too heavy price for the governmental coalition to pay, since instead of the separation of church from State the clericals have been steadily gaining in power throughout the Republic. The clerical schools in Slovakia have been almost entirely retained, and another couple of millions of State funds will be ungrudgingly spent to tickle the palate of a present or a future governmental party. It is only a question whether Illinke, who has carried on a tremendous campaign in favour of autonomy, will be able to whistle back his own followers.

The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia at its National Conference of 1923, in the theses on the national question, took a definite stand upon the situation in Slovakia. Its message was brief: war upon the Czech bourgeois regime, exposure of the reactionary autonomy swindle of the Slovak clericals, complete local self-government for all the communities throughout the Republic, and removal of bureaucratic interference by State officials in local government matters. I am of the opinion that this programme should be extended to include the demand for a separate territorial administrative autonomy for Slovakia. To my mind this demand would meet substantially the needs of the people of Slovakia. Purely from the political standpoint the propaganda for this demand would take the wind out of the sails of the clericals and facilitate the unmasking of their demagogical spouters. The agitation of our Party among the Slovak small peasantry would be given a tremendous fillip; out position in Slovakia would be strengthened, which is of paramount importance to our politics in general; in short, the regime of the Czech bourgeoisie, the whole coalition regime, would receive a fresh blow.

That we still have a wide field for activity in Slovakia, that there are still great masses whom we have to win over was shown in the last elections. These were the town and country council elections held in September, 1923, the first since the foundation of the Communist Party. These elections were such a defeat to the governmental coalition that the Government is even to this day afraid to publish the statistical returns of the elections. A report was published in Narodni Listy which is certainly drawn favourably to the government; nevertheless it confesses that the governmental parties obtained about 400,000 votes as against 915,000 votes recorded for the opposition parties, which means more than a two-thirds majority against the government, and that in spite of all the territories and jerrymandering of the authorities! The votes were divided somewhat as follows:

GOVERNMENTAL PARTIES:

Agrarians–311,000

Social-Democrats–63,000

National Socialists–38,000

National Democrats–16,000

OPPOSITION PARTIES:

People’s Party (Clericals)–432,000

Magyar and German bourgeois parties–248,000

Communist Party–178,000

Jewish Parties–44,000

Ruthenians–16,000

As already said, the returns are inexact and unreliable; nevertheless, they are not favourable to the government, although they were doctored to the disadvantage of the Communists. This much is obvious; the overwhelming majority of the population of Slovakia is deliberately hostile to the present governmental regime of Prague; the overwhelming majority of the working class in Slovakia are on the side of Communism, but we have failed as yet to penetrate into the masses of small peasants and petty-bourgeoisie. In order to win those proletarian elements who are still holding aloof from us, we need no new programme, no new policy, but increased organisational and agitational party work and intense activity in the trade unions. But in order to win over the rural population, which constitutes the bulk of the population in Slovakia, we need an agrarian and national programme of the above-described kind, which should, of course, include also the linguistic and cultural demands of the Hungarian and German minorities. This could easily be done, because as we have already pointed out, the majority of the people in Slovakia are not affected by the propaganda of national hatred against the Germans. All the national oppression existing in this country emanates from the Czech bourgeoisie and from its system of government; it is decreed from Prague, and it does not strike root in Slovak soil.

The German Problem.

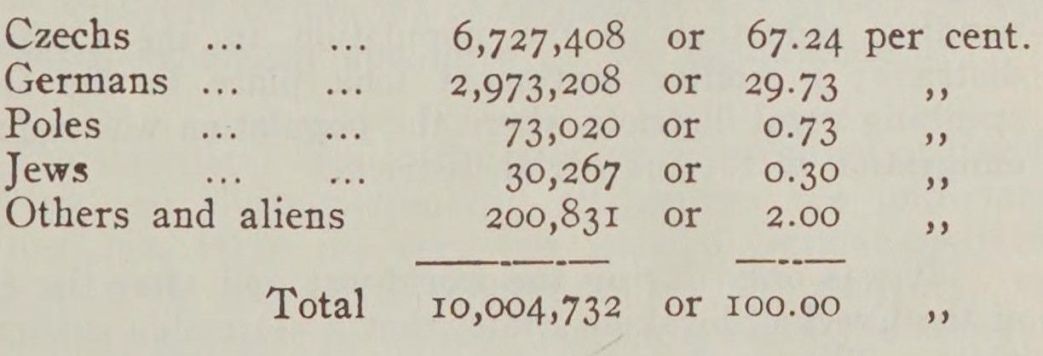

In Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia, in the so-called “historic” or “original” countries of the Republic (which should be particularly taken into consideration in examining the national question), the national composition of the population is somewhat as follows:

Already from this table it may be seen that the national question in this most important economic and political section of Czecho-Slovakia is exclusively a German question.

This is quite the opposite to the situation in Slovakia, where the Germans are not numerous and where they live under different circumstances.

It was also shown by statistics that even in the “original” countries the Czechs have just a two-thirds majority of the population. At the same time the 30 per cent. of the Germans represents a permanently settled population. Little fluctuation was shown among this population by the last censuses taken under the old Austrian regime. The last strong fluctuation in favour of the Czechs occurred in 1890 (the census was taken in Austria once in Io years); at the time of the first industrial development, because the proletatianisation and impoverishment of the Germans was more rapid. Emigration to industrial Germany, high mortality and terrible infantile mortality decimated the German population, while the Czechs, who were still a people of peasants, were not so rapidly affected by these consequences of capitalist development. The legend about the much higher birth-rate among the Czechs has proved to be unfounded. Since the ’80’s the Czechs, too, became strongly proletarianised and industrialised; poverty got them into its grip, and their temporary gains over the Germans were set at nought. A certain process of Germanisation had begun; but it was soon ousted by the recrudescence of nationalist sentiment among the Czech workers towards the close of the 19th century. The German workers had gained by the rise in wages, by the shortening of hours and by the social policies inaugurated in the ’90’s, and their state of misery was somewhat mitigated. The rate of adult and infant mortality had dropped. In this manner the German population was practically brought back again to its former numerical level. If there was an increase of the Czech minority in the German speaking industrial centres, it was accompanied by a corresponding reduction in the population in the Czech rural districts; a similar movement took place in the German speaking rural districts where the population was reduced by emigration to the industrial districts.

It was only during the world-war and after the creation of the Czecho-Slovakian State that a noticeable shifting took place. The Czech national census of 1921 shows that in the “historic countries” (with the exception of the small Czech district) the population decreased by 159,797 or 1.65 per cent., while the Czechs increased by 327,625 or 53 per cent. and the Germans decreased by 508,923 or 14.75 per cent. It is interesting to note that the general average decrease of the population in the districts with a German majority was 5.18 per cent., and in the districts with a Czech majority only 0.11 per cent. The Germans had suffered a great deal more from the effects of the war, for the general misery and famine which accompanied the war were most intense in the industrial districts inhabited by a German majority. Another reason was that the Germans had responded more widely than the Czechs to the call to fight and to die for the glorious Hapsburg dynasty, “for the German cause,” as it was put by the Weiner Arbetterzeitung. But these were only minor causes of the great change. It stands to reason that the establishment of the Czecho-Slovakian State had a tremendous effect upon the national feelings of the Czechs in the German-speaking districts. Many thousands, who for economic reasons had hitherto pretended to be German, now declared their allegiance to their own nation. Thousands of others did so on the chance of gaining advantage by doing so. Many German employees, state officials, petty-bourgeois and even workers turned themselves into Czechs for personal opportunist reasons. The job-hunter now had every inducement to profess Czech nationality under the new regime, just as under the old Austrian regime it paid him to be German. Finally, the Jews, who profess to belong to the Jewish nation (which was not possible in Austria), were almost exclusively German-speaking, and had consequently been hitherto counted as German.

On comparing the relative strength of the Czech and German population on the basis of the census with the relative numbers of votes recorded for the Czech and German parties in the elections of 1919 and 1920, in which the national lines were sharply defined, we find a slightly more favourable picture for the Germans. The ballots were cast in secret; whereas declaration of nationality had to be filed with the census-commissar appointed by the Government.

The statistical data in the relative distribution of Czech speaking and German-speaking settlements are important. We find that there are very few isolated German-speaking settlements in the Czech districts; on the contrary, the overwhelming majority of the German-speaking inhabitants cling together upon contiguous territory, forming a majority of the population in such localities.

According to a German publication the contiguous German-speaking territories comprise 3,191 communities with a German majority with an area of 24,850 kilometres, while the isolated German-speaking settlements comprise 206 communities with German-speaking majorities with a total area of 1,700 kilometres. In the local elections of 1919, in which about 1,585,000 votes were cast for the German parties, no less than 1,363,000 votes, or 86 per cent. must have been obtained in the contiguous German-speaking territories; only 93,000 or 6 per cent. in the isolated German-speaking settlements and 120,000 votes, or 74% per cent. must have been cast by German minorities. The remaining 9,000 votes (or one-half per cent.) belonged to German minorities in the isolated Czech-speaking settlements in the German speaking regions; there were 16 such localities, and the Czechs cast 15,309 votes in them. Comparing the totals of German and Czech votes in contiguous German-speaking territories exclusive of isolated Czech-speaking settlements, we find that the Germans obtained 1,372,678 votes and the Czechs 136,538—a proportion of 91 to 9.

The Czech statistician, D.A. Bohac, puts the total German-speaking territory of Czecho-Slovakia at about 25,000 kilometres and 2,937,000 inhabitants. Comparing these figures with those of the German authority just quoted, and bearing in mind that the size of German-speaking territory in Slovakia is rather negligible and that the average of ratio of the number of voters to the number of inhabitants under Czech law is about 1 to 2, there is hardly any appreciable difference between these two sets of figures emanating from the Czech and from the German sides. We may, therefore, calculate on the basis of the figures furnished by Ogerschall, that Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia are really divided into three national territories and in the following manner:

Czech-speaking territory, about 53,000 sq. kms. Or 67.4 per cent.

German-speaking territory, about 25,000 sq. kms. or 31.9 per cent.

Polish-speaking territory, about 700 sq. kms. or 0.7 per cent.

Out of an area of about 78,700 square kilometres.

This ratio is further confirmed by the statistics on population which show that the German-speaking inhabitants in the Sudetic countries are concentrated in fairly compact settlements.

The German-speaking districts of Bohemia, the population of which includes no less than two million Germans, are by far the most important industrial districts of the country. Only in Moravia and Silesia are the German speaking districts more agrarian. The glass, porcelain, linen, cotton, and paper industries, as well as the cultivation of red cabbage, are located chiefly in the German-speaking districts. The German inhabitants of all classes are more inclined to industrial pursuits than are the Czechs. In short, the German-speaking districts are economically the most important. regions of Czecho-Slovakia. Because of their economic importance, which renders them indispensable to the existence of the State as a capitalist state in a capitalist world, these districts were arbitrarily annexed to the State, regardless of nationality or the wishes of the population.

Bearing in mind that the Germans in Czecho-Slovakia are by no means inferior to the Czech people, either culturally or politically, there can be no doubt as to the extreme importance of the German question to the State, if only on these domestic grounds alone, to say nothing of the larger issues of foreign policy.

The question becomes even more serious when its international character is taken into consideration.

There are approximately three million Germans in Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia who not only ethnographically and linguistically belong part and parcel to the 80 millions of Germans in Germany proper, but are closely bound to it by their settled habits and by the whole of their cultural and above all, their political life. The German settlements in the Sudetic countries are separated only by mountains and state-boundaries from the rest of the settlements of the German nation. It is only in the valley of the Glatz that the Czech settlements extend to any appreciable degree to the borders of the German Empire. The frontiers on the German and Austrian sides are for the major part in districts where the German population is in the majority. Over a long stretch of country, starting from Oberberg in the Upper Silesian corner, via Bodenbach and Egar, and all the way to Pressburg, the Czecho-Slovak State is hemmed in by Germany and Austria from North, West and South. It is indeed a miracle that the Czechs have managed in this geographical situation to maintain themselves as a nation throughout the centuries, a miracle explained only by the fact that there was no united national German State. It sounds paradoxical to-day; nevertheless, it is not historically incorrect to assume that the Czechs owe a great deal to the Habsburgs for the maintenance of their national existence. Austria, as already admitted by Palanching, was the salvation and security of the Czech nation. If the dismemberment of Austria has given the Czechs their national independence, it was possible only because the power of Germany was crushed at the same time. An indispensable condition to the existence of the Czecho-Slovak State in its present boundaries within the capitalist order in Europe is the impotence of Germany, the perpetuation of the present balance of power in Europe. The restoration of a strong and mighty capitalist Germany would render it impossible for seven million Czechs to continue the subjugation of the three million Germans who belong to a nation of 80 million people; and this would mean the end of the Czecho-Slovak State. A Czecho-Slovakian State within the proper boundaries of Czecho-Slovakia under the capitalist system would be practically impossible, both from the economic and strategical point of view. The principal railway arteries from Prague to Bruenn, and from Prague to the coal mining and industrial centres of the Ostrau district, that is, the railway communications with Eastern and Northern Slovakia, run through German-speaking territory!

Herein lies the fundamental reason for the nervous zig-zag policies of the Foreign Office of Czecho-Slovakia. It seeks to avoid any open quarrel with Germany and Austria, but at the same time to keep them both in their present state of economic and political impotence; however, it would like to prevent their economic collapse, because such a calamity would be of great danger politically and socially to the bourgeois republic of Czecho-Slovakia. | What the Czecho-Slovakian Foreign Minister, Herr Benes, fears most, is a break-up of the Anglo-French entente, and a rapprochement between a big European power and Germany, which is quite conceivable in view of the circumstances described above. this accounts also for the nervous journeys of Herr Benes between London and Paris during last year. When the Anglo-French Entente seemed to be in peril, Benes sought refuge in the “Little Entente,” so as not to be dependent entirely upon the big powers. When Poland would not join, when Yugoslavia carried on her own little game with Italy, and when the break-up of the Entente seemed imminent, the only way for Benes to be consistent in his own policy was to throw himself entirely into the arms of Poincaré. Imperialist France is the only power in capitalist Europe which has both the interest and the ability to keep Germany down, and, under the circumstances, there is nothing left to Massaryk, Benes and Kramer than to pray to Almighty God for a long lease of life to the foreign policies of Poincaré.

The net result of national emancipation and the establishment of the State under the leadership of the bourgeoisie is this: the entire fate of the Czecho-Slovakian nation is bound up for better or for worse with the balance of power in capitalist Europe, or rather with the hegemony of France. It is with this that the Czecho-Slovakian Republic will stand or fall. Under the old Austrian regime, the Czechs as a nation were not free and independent, and they were oppressed politically and nationally; but their existence as a nation and their future development were far more secure than in present-day capitalist Europe. The Czech statesmen could hope only to become Austrian ministers, not Czecho-Slovakian presidents and ministers; but they could sleep more peacefully than to-day.

The Communist Party of Czecho-Slovak perceived this situation from the very beginning, and it did not fail to point it out to the masses of the Czech and German workers. At the inaugural conference of the German section of the Czecho-Slovak Communist Party (Reichenberg, March, 1921) and at the first regular conference of the United Communist Party of Czecho-Slovakia (Prague, February, 1923), our comrades expressed their views upon this question. In its theses, the Party pointed out to the Czech workers, peasants and petty-bourgeois into what situation the Czech bourgeoisie has guided the nation. It told them that the victory of the European proletarian revolution alone would remove all the dangers which beset the liberty and independence of the nation, that the existence and further development of the nation would be secure only under a system of federated Soviet Republics in Europe. In the event of the redistribution of power in capitalist Europe, the only real factors opposed to German imperialism would be the class struggle of the German proletariat, and the power of Soviet Russia, the true defender of the small nations.

The German workers of Czecho-Slovakia were already told by the Reichenberg conference that any irredentist movement would only serve the interests of German capitalism and imperialism, and of international reaction.

The experiences of the German proletariat in the former Austrian Empire have taught it that national oppression means more oppression and reaction for the proletariat of the “ruling nation.” The fusion of the German-speaking districts of the Sudetic countries with a recuperated capitalist Germany could be effected only under the banner of imperialism and reaction, and it would simply increase the misery and slavery of the German workers. Therefore, the German workers should not shout: “Deportation from Czecho-Slovakia!” but should rather unite with the Czech and Slovak workers for the common fight, for the overthrow of capitalist domination, which will remove national oppression. The Reichenberg conference warned also against any “revolutionary” irredentism towards the proletarian revolution in Czecho-Slovakia in the event of a victorious proletarian revolution in Germany. For such irredentism would not strengthen but weaken a proletarian Germany and menace it with military complications, while the Czech revolution would be crushed and the Czechs driven into the army of the counter-revolution, and the best protection of its flank on the South-East would be the strengthened and united revolutionary action of all the nations of Czecho-Slovakia, which wound eventually bring victory to the proletarian revolution in that country as well. The votes cast in October, 1923, by the Czecho-Slovak workers who were influenced by our propaganda, has shown that the workers of all the nations of Czecho-Slovakia endorse our policy at the decisive hour.

But this political task confronts us only during periods of acute revolutionary tension. At ordinary times we are merely confronted with the question of policies of national oppression as practised by the Czech bourgeoisie against the Germans, and of our attitude to such policies. The Czech bourgeoisie seems determined to “un-Germanise” the Germans and to turn them into “Czechs.” This policy manifests itself everywhere: in the schools, in the language question, in the distribution of government offices, in the agrarian reforms, and so on. It cannot assume the brutal forms and huge dimensions of the German anti-Polish policy and of the Magyar national policies before the revolution. The existing co-relation of forces prevents this in spite of Germany’s helplessness. Official statistics indicate that only 1.7 per cent. of the German children are attending non-German schools, and the number of cases in which German children are compelled to attend Czech schools is insignificant. But for a cultured nation, the workers, peasants and petty-bourgeoisie of which attach such wide importance to the school, the subordination of its educational system to the whims of an alien bureaucracy, and the consequent disruption of the system, seems an extreme form of nationalist oppression. The language question is treated only from the standpoint of the dominant nation, which is again a source of injustice and oppression. Many thousands of German state officials are suffering from unjust dismissal, from unwarranted transfers, and from irrelevant language-tests at civil service examinations. The agrarian reforms and the distribution of large estates is carried out not merely in an anti-social manner, but it is deliberately calculated to promote Czech colonisation in the German-speaking districts. Many questions are handled in a silly and idiotic fashion with the aim of subjecting the Germans to all sorts of petty irritations which are embittering them. But the cap to the climax is the arrogant Prague centralism, which is becoming more aggressive day by day, and which aims at reducing all local self-government to a mere farce. It is the German worker who is hit the hardest by the consequences of these policies of national oppression. The elementary schools are the only ones to which the worker is able to send his children. The language difficulties also cause the greatest hardships to the worker, who is less able than the bourgeoisie to learn languages and who cannot, like the latter, afford to hire Czech-speaking lawyers and clerks to attend to his dealings with the authorities and the courts. The petty officials and workers are victimised more than any other by chicanery in the government services described above (the German railway workers are particularly harassed by the Czech authorities). National oppression has imbued the German petty-bourgeoisie, the peasantry and a section of the workers with intense nationalist sentiments, which renders more difficult the class struggle of the German proletariat against the German bourgeoisie.

It goes without saying that the fight against national oppression constitutes one of the tasks of the Communist Party of Czecho-Slovakia. The Party took it up from the very first, and the Prague Conference of February, 1923, formulated this task for the first time. The principal demands were formulated as follows: removal of centralism in the administration of State-bureaucrats from the local councils; complete local self-government; local control of the educational system; solution of the language question from the standpoint of practical necessity, giving each citizen the right to negotiate with the authorities in his own language. Owing to many other pressing tasks, this stand of the Party upon the national question has been scarcely utilised in propaganda and agitation, and a systematic campaign against national oppression, and for the collection of materials and discussions in the press, has only just begun. The Communist fraction in Parliament accomplished something on this question, for example, the protest raised against the persecution and chicanery practised against the German workers on the State railways.

The necessity of fulfilling this task and the fruits which may accrue from such work are indicated by two facts:

(1) The proportion of strength between the Communists and Social-Democrats among the German workers of Czecho-Slovakia is far from favourable; as a matter of fact, the latter out-number the former by more than two to one. (2) The communal elections last autumn showed a strong drift of workers of German Nationality from the Social-Democratic ranks into the bourgeois parties, particularly into the Fascist organisations. Our influence extends at most to one-fourth of the German workers: our position among the German workers is weaker than among the Czech workers, of whom we, as the strongest party of the working class, have about one-third. Our following among the rural and petty-bourgeois German population of Czecho-Slovakia is not worth speaking about; we have not even begun our work among these people to the extent that we have done on Czech territory.

The Polish Problem.

The slice of Teschen territory (in the eastern portion of the former Austrian Silesia) had to be awarded to Czecho-Slovakia because it affords the only convenient railway communication (via the former Kauschau-Oberburg Railway) with Northern and Eastern Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia. This vital artery of communication, which connects from East to West over the long, narrow stretch of the country, cuts so close into the Polish border that it can easily be captured by artillery fire at Teschen from the Polish side. Of course, the government would like to remove this strategically weak point. This explains the official statistics which purport to show that 13.2 per cent. of the Polish school-children attend non-Polish, i.e., Czech schools. With Poland, as with Hungary, the Czech government made no agreements on the questions of State citizenship, and the conditions in this district are as flagrant as in Slovakia. The majority of the Polish population of Czecho-Slovakia are workers, consisting chiefly of miners and metal-workers. The sympathies of the mass of these workers are on our side; but the influence and nationalist propaganda of the Socialists from Poland are still strong, and lately many Polish workers joined the Czech Social-Democrats in the trade unions and in political activity because the latter promised to secure the rights of citizenship for their members. The question of the Polish workers is another task which the Communist Party of Czecho-Slovakia must fulfil more completely in the future than hitherto, be- cause these workers play an important part in one of the most important industrial districts of the Republic.

Carpathian Ruthenia.

Carpathian Ruthenia represents an important problem in itself. This country was annexed by Czecho-Slovakia by virtue of Articles 10-13 of the Treaty of St. Germain on the 10th of September, 1919, for reasons of international politics. Ethnographically and linguistically the bulk of the population belongs to Russia, notably to the Ukraine; but it was not desirable to leave the country to Poland or to the Ukraine, or to a Soviet Republic. Carpathian politics were also played in the United States during the war. On the basis of a resolution adopted in America in July, 1918, by the “National Council of Hungarian Russians,” a covenant was signed at Philadelphia between this organisation and Massaryk which guaranteed “absolute independence” to Carpathian Ruthenia. This condition was also included in the above-mentioned Articles of the Treaty of St. Germain. Thus far the Czech government has failed to fulfil the terms of the Peace Treaty, and it has not even shown any honest intention of doing so. On the contrary, it has inflicted upon the little country a bureaucratic police and military regime even worse than that of Slovakia. What has been written about Slovakia applies to an even greater extent to Carpathian Ruthenia. The Ruthenians of the Carpathian forests were driven into starvation and despair by this system.

The attitude of the Communist Party upon the Carpathian question was clear from the very first. While demanding the distribution of the lands, forests and pastures of the big estates among the poorer peasants, we insisted also on the fulfilment of the pledge of independence that was accorded to the Carpathians by the terms of the Peace Treaty. Our Party was the only one which championed the cause of the poor and oppressed Carpathians, in Parliament and in the press. This, and the tremendous effect upon the poor Carpathian villages of the tidings of the great liberation of the Russian peasants by the Bolshevist revolution, brought us victory in the elections, which was not at all unexpected. In Carpathian Ruthenia, the majority of the population of the countryside are on our side. It will be our next and immediate task to transform this adherence and sympathy into active and conscious solidarity for the revolutionary action of the masses. Our economic, political and national programme here is quite clear.

The population of Carpathian Ruthenia is not composed of one nationality which the following figures will illustrate:

Carpathian Ruthenians–372,884 or 61.48 per cent.

Magyars–102,144, 16.84%

Jews 380,0507, 13.20%

Czecho-Slovaks—19,737, 3.25%

Germans—10,460, 1.72%

Others and aliens—21,384, 3.51%

Total 606,468, 100.00%

Among the Magyar population there is a strong proletariat, the majority of which is in our camp. The Jews in this country are also strongly proletarianised, but they are orthodox and are inclined for the most part towards Jewish nationalism. In the North-west are the Slovak peasants, who are as susceptible to our propaganda as the Ruthenian peasants. The Czechs consist almost exclusively of officials, soldiers, gendarmes and State employees. The Germans are mostly peasants (colonists like the Germans of Zips and Siebenbuerger). National strife is almost unknown among the population. Everyone wants to be rid of the Prague regime. Autonomy is demanded even by the non-Ruthenian population. The internal national questions present no difficulties whatever. The national question was raised by other questions, for instance, whether the Carpathian Ruthenians are Great Russians (Moscovites) or Little Russians (Ruthenians, Ukrainians). Although the great majority of these poor fellows are still illiterate—conflicts arose between various factions over an alphabet and a grammar! The masses remain unaffected by these squabbles. All they want is Land and Liberty.

Czecho-Slovakia is a small country, but its national problems rank in variety and importance with those of the big states. In this respect, as in many others, it is heir to the former Austrian Empire. The labour movement of Austria was led astray by national problems, which broke up its political and trade union organisation. The leaders of the Amsterdam and Second Internationals in Czecho-Slovakia, like true heirs of the pre-war reformism and social-patriotism of Austria, have bequeathed the proletariat in the new State a labour movement torn with national dissent and took no step to bring about international solidarity.

But the Communist International, for the first time in the history of the countries now belonging to Czecho-Slovakia, has created an international, united workers’ party—the Communist Party of Czecho-Slovakia, while the Red International of Labour Unions has, for the first time, brought about a united trade union movement that is free from national antagonism. And it is the Communist Party alone, under the leadership of the Communist International, that will master the national problem in Czecho-Slovakia. The question can only be solved by the formation of a Czecho-Slovakian Soviet Republic in a Socialist Europe.

(Translated by M. L. Kortchmar.)

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF pf full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/new_series/v02-n04-jul-aug-1924-new-series-CI-grn-riaz-orig-cov-r2.pdf