Student radicalism was new phenomenon in the early 1930s. Below, Jew-baiting accompanies red-baiting as the football team and fraternities, whipped up by the press, aid right-wing administration in reimposing reaction on the campus of the University of California.

‘Vigilantism at U.C.L.A.’ by Claudie Little from Student Outlook (S.L.I.D.). Vol. 3 No. 2-3. November-December, 1934.

COLLEGE administrators, trustees and faculty members have been so accustomed to looking upon the university as an instrument for the perpetuation and strengthening of the status quo, that the appearance of a student movement which demands at least the neutralization of the university structure—if not its alignment with the forces working for a warless world—has thrown them into a panic. At Santa Clara the Editor of the undergraduate sheet was expelled for an anti-war editorial. The same happened to the editor of the University of Oregon paper for criticizing the Republican candidate for Governor. President Robinson of C.C.N.Y. unblushingly declares that: “the time might come when it would be clear that a college cannot permit its students to publish papers.”

Even more ominous has been the procedure adopted by several administrations to combat the left-wing student movement. As if afraid to invoke the disciplinary powers of the university, responsible administration officers are calling upon patriotic students to purge the campus of radical influence. The appearance of a leaflet at San Jose State College led the President to write in the college newspaper the following invitation to disorder and stool-pigeon tactics in his college:

“When it comes to a direct and vicious attack like that, the time for discussion is over. I hope every true citizen on this campus, every one who loves the United States of America as well as his college, will assist in the eradication of this festering sore. Will all loyal groups, clubs, classes and societies act immediately. Make plans to get the necessary information. If you know members of the group, please feel quite free to take them to the edge of the campus and drop them off. I am very sure if they continue their efforts beyond the campus bounds the San Jose community is well prepared and willing to take care of them.

“Don’t make any mistake, young people. This is a direct attack, vicious and senseless, upon our free government. It jeopardizes seriously the welfare of all of us, Certainly nobody wants a gang like that to run our nation, and now’s the time to put a stop to the movement here…”

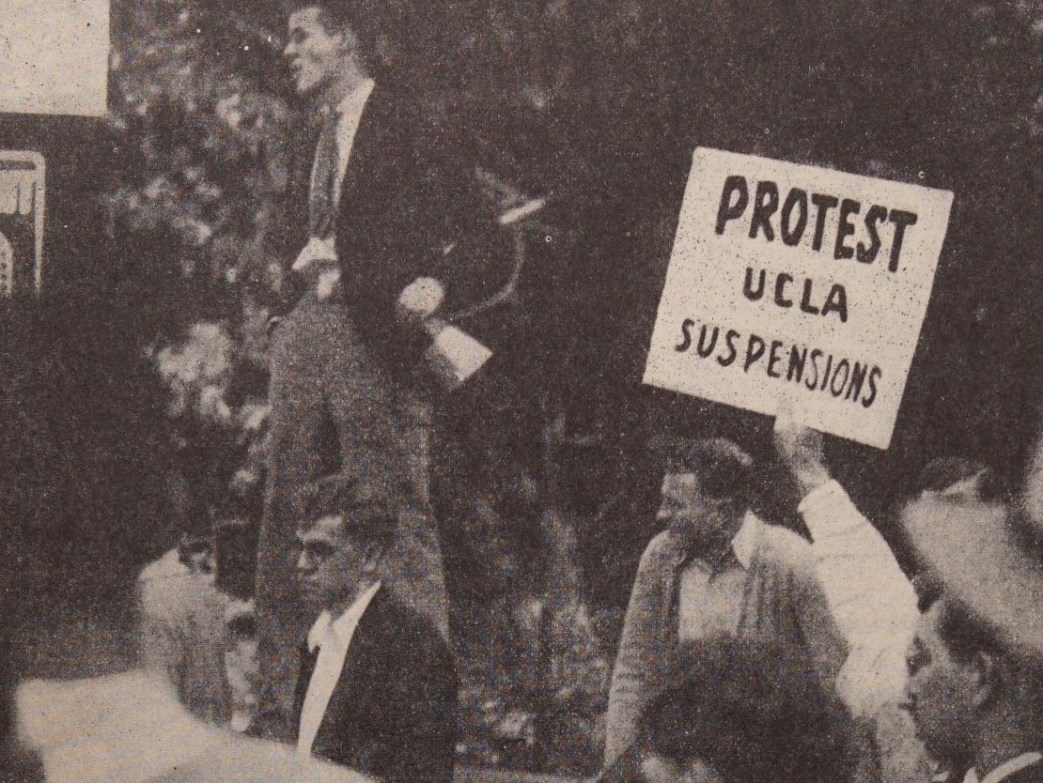

However it is the University of California at Los Angeles (U.C.L.A.) which best exemplifies this inflexibility of administrative minds and habits because of the pressure of the reactionary influences of the community, and in a large part because of actual ossification. When 3,000 U.C.L.A. students meeting spontaneously underneath Provost Moore’s windows over the suspension of five fellow students, were calmed into singing their alma mater “Hail Blue and Gold,” Los Angeles papers hailed this inspired gesture of campus patriotism as having put an end to the danger of campus violence. Actually, however, the danger of violence had just begun. On November Ist, Dr. Moore broadcast the following appeal to the fraternity men and athletes of the country:

“It will be best when we are not any of us Laodecean about our country. There is a psychology and strategy of bringing about a revolution. It is not an exact science and is largely the work of Leon Trotsky.

“The first direction in that science is: ‘Put the people to sleep.’ To cry: ‘Wolf! Wolf!’ so often that when the wolf attacks no one will pay any attention.

“The revolutionary student leaders are instructed to do two things: 1. To organize all the revolutionaries; and 2. To make the great mass of students neutral.

“They will not be neutral hereafter.

“I know of no better work for the fraternities and sororities in the colleges and universities of the United States than for their people to become the active helpers of the United States in its day of difficulty. If the young people do that they will repay us for all the patience we have had with them.”

The football team, which of course has always been noted for its loyalty to the ideals of higher education, was, with the organization presidents, one of the first groups to respond to this dignified appeal of the Provost. At the height of the meeting of the 3,000, they organized themselves into a battering ram, which swept through every cluster of students discussing the suspensions. The next evening at a meeting of athletes and other “student leaders” it was decided to place vigilantes on the campus. According to the Los Angeles Herald and Express: The vigilantes came from the ranks of the husky, stern-faced athletes who met in a drizzling rain on the Westwood hillside last night and vowed to purge the campus of radicalism “by force if necessary.”

U.C.L.A. has an impressive history of reaction to its discredit. The squelching of an anti-compulsory R.O.T.C. petition, signed by 1700 students in 1932; the suppression of the off-campus left-wing controlled Social Problems Club, in the same year; the suspension of the conscientious objectors, Alonzo Reynolds and Al Hamilton in 1933—these are but three instances. In this background is included an incident significant because it marks the origin of Provost Moore’s firm belief in the fundamental dishonesty and unprincipled trickery of student radicals—the peace mass meeting at U.C.L.A. two years ago, at which Albert Einstein, announced as the speaker, was substituted for, without previous announcement, by Communist speakers. Dr. Moore never has accepted the students’ story that Einstein was unable to attend at the last minute, owing to factors entirely outside of their control, but has persisted in the belief that he was deliberately sold out. These events build up a picture in which the suspensions of Monday, October 29, for the first time constitute an official declaration of war by the administration upon all students on whom suspicion has been cast.

Who were the five students ousted on October 29? How red were they? And what were the charges against them? Here is how they line up: Johnny Burnside, student body president, non-fraternity man, and R.O.T.C. officer, sincerely trying to establish a new deal in the student body government; Sid Zsagri, forensics chairman, and Tom Lambert, head of the men’s board, both appointed by Burnside, both non-fraternity men, and both prominent in Youth-Epic circles; Mendel Lieberman, also appointed by Burnside, chairman of the scholarship and activities board, whom no radical campus group would claim as one of its own; Celeste Strack, Phi Betta Kappa, national woman’s debate champion last semester, coming to U.C.L.A. as a senior this fall with a record of outstanding N.S.L. leadership at the neighboring University of Southern California last spring. The charges against the men, in Provost Moore’s words, are: “using your student office to aid the National Student League to destroy this university” against the coed, “for persistent violation of the regulations of the University, including the holding of Communist meetings on this campus.” As to the truth of these charges, suffice it to say that there is not a shred of evidence to sustain them, and no one realizes that better at this moment than Ernest Carrol Moore, Provost of the University of California at Los Angeles.

The factors leading to the suspensions form an interesting entanglement of separate elements. Basic, of course, is the general reactionary atmosphere and constant American Legion pressure. Coupled with this is the necessity of attracting donors of large gifts to an expanding institution handicapped by decreasing State appropriations, and increasingly coming to be known as a hot-bed of radicalism. Into this set-up, in the fall of 1934, came three student body officers who took seriously the responsibility of student self-government. The intelligent appeals of Burnside, Zsagri, and Lambert won over an indifferent council to an investigation of the accounting by hired non-student representatives of student body funds, which they had reason to suspect would not bear too close scrutiny. Then followed the refusal of the council to sponsor, with proffered alleged munitions makers’ funds, a patriotic essay contest for Navy Day, and the rejection of the customary American Legion application for a parade at U.C.L.A.’s Armistice Day football game, which in previous years has netted something like $6000 above the ordinary gate receipts. (This latter action was later rescinded, at the last council meeting before the suspensions.)

Throughout this series of events ran the student demand for a free open-forum. The council, voting to sponsor such a forum, was opposed by the Provost, who offered them instead a forum directed by four faculty and four student members. This proposal at first was turned down by the council, which, after discussing the advisability of a campus referendum, underwent a change of heart and tabled the matter until its November 7 meeting (coincidentally enough, one day after the gubernatorial elections.) On Wednesday, October 17, an unofficial student group met to discuss the possibility of using their constitutional right of initiative to secure a student body vote on the issue, the group having set its heart on a forum before November 6. The meeting was adjourned, to reconvene for completion of plans on Friday, October 26. This latter meeting was attended by a miscellaneous group—several students affiliated with no organization, a good representation of N.S.L. members, two members of the student body council, and among others, two campus policemen. On Monday, October 29, at 1 o’clock, without warning and without a hearing, the five students received notices of their suspension.

In their usual weekly meetings that night, the Greek letter organizations were divided in their stand, although the metropolitan newspapers, reporting that the “Greeks” had approved the suspensions, intimated that thereby 80% of the students were backing up the administration. Later the newspapers were forced by events to admit that only 43 presidents had supported Moore, this latter number being by no means representative of unanimous approval by the fraternity and sorority groups, who comprise not even fifty per cent of the student body. Non-fraternity men, whose officers include Burnside, Zsagri and Lambert, in a regular meeting of their own organization, denounced the suspensions as provoked by campus politics.

What is to come is an open question. As for the ousted students: to an offer of reinstatement which already has been made by the Administration, and which would restore only Burnside to office, they replied, “We cannot accept an arrangement which, by depriving us of our student offices, implies that we are not yet cleared of the stigma which by his (Dr. Moore’s) own admission, has been falsely attached to us.” In this statement, they admittedly turn their backs upon the free-speech issue, thereby separating themselves completely from Celeste Strack. (The Los Angeles chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union is acting in her behalf, and is planning to carry her case to the courts, if necessary.) The lengths to which they are willing to go in order to be cleared of implications of Communist leanings is indicated in a further statement: “Our suspension has deprived the administration of valuable allies,” thus intimating that they are ready to help in the purging of Communists.”

This right-about-face of the four student officers serves to increase the colossal confusion in the minds of the majority of students. And it plays directly into the hands of the red-baiters, for these students seem willing to go to any lengths to prove that they are as good reactionaries as can be found anywhere on the campus. And on November 14, the four students were reinstated following an investigation by President Sproul which assured him that the four were loyal to college and country.

With regard to the real issue, there seems to be little doubt that what is involved is an attempt to establish the campus as an institution of 100% Americanism, as witness the following pledge, adopted at a meeting of athletes and other student leaders two days after the suspensions: “We, the U.C.L.A. Americans, have united in an organized effort to further Americanism and rid the University of California at Los Angeles of communistic and radical activity.” These words mean only one thing—vigilantism, with all students suspected of even the mildest liberalism as the victims.

Nor are other aspects of fascism likely to be left out, particularly that familiar ear-mark—Jew-baiting. On Friday, November 2, students arriving on the campus were greeted by the sight of stalwarts engaged in pinning Small American flags on all within their reach, at the same time, offering an anti-red pledge for signature. When one student, unmistakably recognizable as Jewish, refused to accept a flag, he was promptly and loudly warned, “You dirty Jew, we’ll run you off the campus along with the reds!” A loud-speaker system, ballyhooing for Alumni homecoming that evening, blared his name out over the campus. There were few others who refused the flags. How many accepted them because they were unaware of the factors behind this display of patriotism, and how many others wore the flags reluctantly, under the influence of the prevailing fear psychosis, it is impossible to conjecture.

This concerted attempt to purge the U.C.L.A. campus may well be the beginning of an organized student fascist drive in the United States. The experiences at Westwood offer a warning to class-conscious and militant students everywhere, and a challenge to rally their forces for the struggle to come.

Going through a series of names in the 1930s starting with Revolt, then Student Outlook, then New Frontiers, and finally Industrial Democracy these were the publications of the Socialist Party-allied National Student League for Industrial Democracy. The journal’s changes in part reflected the shifting organizations of the larger student movement.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/student-outlook/v03n02-03-nov-dec-1934-student-outlook.pdf