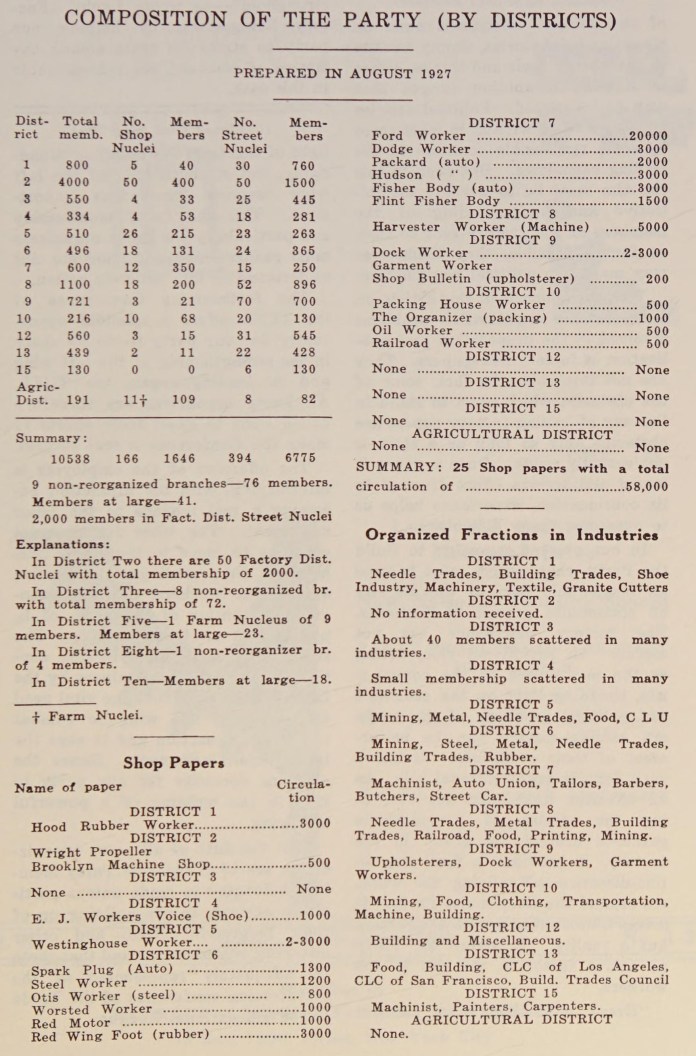

Organizing the workplace, especially in large or varied institutions, required a way to agitate, to collect and share information, and to organize. It required a media. Rebecca Grecht’s internal Communist Party report includes an invaluable breakdown of the Party’s 10,500 members in 1927.

‘Factory Newspapers’ by Rebecca Grecht from Party Organizer. Vol. 1 No. 2. December, 1927.

Comrade Grecht is a member of the New York District Executive Committee and was head of the Factory Paper Committee. Comrade Grecht was recently appointed National Field Organizer.

In the period which has passed since our Party was reorganized on the basis of factory units, we have developed various new forms of activity which will play important parts in the building of a mass Communist party in America. Among them is the publication of factory newspapers—Communist shop organs issued by our nuclei.

Today we may correctly state that such papers are no longer a novelty to us. Almost every district in the Party has undertaken their publication—notably Detroit, Cleveland, Chicago, and New York—with varying degrees of success. In fact, an examination of the papers issued shows, in spite of the shortcomings, a surprisingly good grasp of the essentials of factory organs—surprising, because of our lack of experience.

At the present time, however, there is evident a slackening down of effort in this direction. Some of the shop papers have been suspended; others, entirely discontinued. This condition must be remedied. As a means of extending communist influence in shops and factories, as a means of activising our party membership, the significance of factory newspapers is tremendous. We must revive old papers and issue new ones. This is one of our highly important immediate tasks.

Unquestionably there are difficulties involved in issuing shop papers. The problems of organization, of publication and distribution, of writing and editing, of the correct correlation of material, all must he considered. But once a definite method is worked out and systematic attention given, the problem becomes simplified and the results decidedly encouraging.

To carry out this task effectively, every district, sub-district, and city organization should establish committees whose special charge shall be the general supervision of factory newspapers in their territory. The placing of definite responsibility for this work is essential.

These committees must aim to issue papers in every shop and factory of several hundred or more workers where party members are employed. It is not only in huge plants employing thousands, as in the Ford factory in Detroit, but also in relatively small factories employing only a few hundred, as the Wright Aeronautical Corporation in Paterson, New Jersey, that shop papers can have marked effect. Furthermore, it is not necessary to wait until a large nucleus has been established in a plant before issuing a paper. While this is, of course, most desirable, often one or two live wires, perhaps with the indirect assistance of some sympathizers, can undertake publication.

Nor is it necessary to start on a grand scale. Many comrades visualize the factory newspaper as a sort of miniature copy of a daily newspaper. They think it must be printed, have at least four or six pages, and in general simulate the appearance of the communist press. Lacking the required financial and technical resources, they become discouraged and decide it useless to start. And when they put out the first issue on a grand scale, it takes many months until another issue is printed and sometimes it is the only issue. This causes confusion, and suspicion among the workers. This conception has undoubtedly prevented the issuance of a number of shop papers. It is a case of a commendable ambition, which must, however, be checked. For the present, we must set our minds firmly on the possibilities within our reach, and above all strive for regularity in the issuance of the shop papers. A printed shop paper is best, of course. Where this is not possible, a mimeographed one will serve the purpose. A paper having space enough to deal with all the economic and political problems confronting the workers in the shop should be our aim. But where there are no facilities, a single sheet, mimeographed on both sides is a good start. Printing should be considered only when, through contribution, assistance from the district or local treasury, affairs for the benefit of factory papers, or proceeds from the sale of the paper where selling is possible, a fund is available for that purpose.

Another problem involves the actual organization of the paper. How to start, how to get the news and write it up, are questions every unit faces when it begins planning a shop paper. The method used in New York with considerable success may well be applied in other districts.

To begin with, either a member of the factory newspaper committee or another comrade who understands the problems of shop papers, is attached to the nucleus. A preliminary meeting of the nucleus is called at which, under the direction of this comrade, the general problems of factory newspapers and the specific needs of the unit are discussed, and the members are asked to talk about their shop—to tell about wages, hours, etc. A good response can be obtained in this way. As the members speak, the facts are jotted down. Then for the next meeting, each one is assigned to write up what he has told, either in a brief article, or in a letter form. When the material is ready, the members discuss it, and if necessary, rewrite it to meet the criticism that may be offered. When the material is finally approved by the committee in charge, the paper is issued. Then, conferences of all comrades participating in the publication of factory newspapers are held to exchange experiences and analyze the papers.

While the desired results are not always immediately obtainable, and often the comrades in charge may be compelled to do most of the writing, yet, by following this method, the initiative of the comrades in the shop can be developed, their cooperation assured, and a general interest in the work aroused.

It is well to bear in mind that the factory paper must become the work of the factory unit itself. If they are simply products of district committees, the material gathered and written by some one comrade who has no direct connection with the factory, then the effectiveness and value of the paper will be correspondingly diminished. True, very many of our comrades in the factories have the idea that only journalists and experts in the English language can write about shop problems, and are afraid to express themselves in writing. This illusion must be broken. We do not desire the language of the school or newspaper office, but the language of the worker. Emphasis must be placed on brief stories, simply written as the worker feels and thinks, either in English or another tongue that may be translated. Political articles may have to be written in most cases by some responsible comrade of the leading committee. But even in this the aim must be to develop the initiative and understanding of the members of the factory unit so that, as far as possible, they themselves may make the political contribution.

We have touched in this article on a few of the organization problems involved in the preparation and publication of factory newspapers. They are not insoluble. In fact, some of the obstacles which seem to stand in the way of issuing factory papers are obstacles only so long as a start is not actually made. Once a paper is issued and serious effort directed to its continuation, experience helps us to overcome many difficulties.

In our present campaign to Build the Party, shop papers must become an inseparable part of the activity of communist groups in factories. The factory newspaper has not merely an agitational role, acting as the mouthpiece of the communists, shedding light on the economic and political problems of the workers, raising slogans for the betterment of their conditions. It has a very definite organizational role. As an effective instrument for extending the circles of sympathizers gathered around the group in the factory, it provides a first step in the direction of rallying the workers around the Communist Party. It makes Communism not an abstraction but a reality. It makes the Party an active factor in the life of the workers.

“Every work-shop must be our stronghold”—so wrote Lenin. Factory newspapers, by helping our party to strike its roots among the masses of workers, are indispensable in this task.

The Party Organizer was the internal bulletin of the Communist Party published by its Central Committee beginning in 1927. First published irregularly, than bi-monthly, and then monthly, the Organizer was primarily meant for the Party’s unit, district, and shop organizers. The Organizer offers a much different view of the CP than the Daily Worker, including a much higher proportion of women writers than almost any other CP publication. Its pages are often full of the mundane problems of Party organizing, complaints about resources, debates over policy and personalities, as well as official numbers and information on Party campaigns, locals, organizations, and periodicals making the Party Organizer an important resource for the study and understanding of the Party in its most important years.

PDF of issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/party-organizer/v01n02-dec-1927-Party%20Organizer.pdf