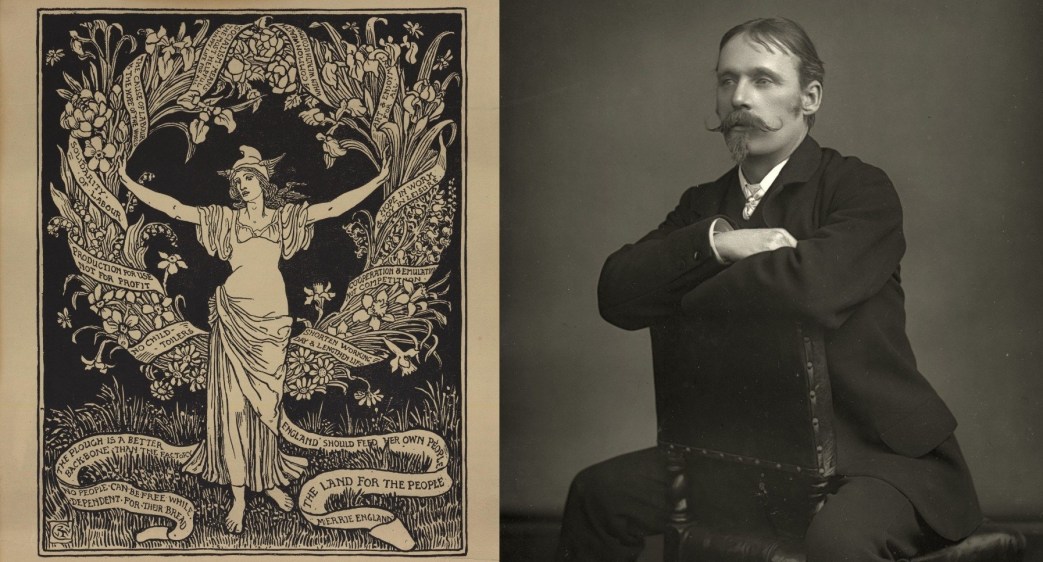

An obituary recounting the life and work of artist Walter Crane, co-worker of William Morris and creator of extraordinary and indelible images that would help to define the early Socialist movement.

‘Walter Crane’ by Robert Heele from Young Socialist Magazine. Vol. 10 No. 3. March, 1916.

The passing of Walter Crane has left a sad gap in the ranks of those who built up the modern Socialist movement in this country. When he joined us, our numbers were so few as almost to justify our opponents’ jibe that the Socialist Party of Great Britain could be packed into a four-wheeled cab. Socialism was not unknown, it was discredited, and advanced thinkers of all classes were interested in other directions. It is true that there was a nucleus of political thought round which we were to gather. The Socialism of Robert Owen had given a basis to Chartism which persisted to the times of the International and thus joined hands with Marxism, but as far as the average thoughtful working man was concerned his political interests were limited in the North of England to Trade Unionism and in the South to Republicanism and Secularism. Among the middle classes the Christian Socialist movement of Maurice and Kingsley had exhausted itself and was almost forgotten, and the word Socialist was a term of abuse connoting every threat to the sanctity of person or property.

This is not the time to describe the history of our movement, but it must be said that in London and the South of England it was in the beginning an agitation carried on by members of the middle classes among the working classes, with great and almost startling success. A leading Liberal once described to the writer his astonishment at the result. At one election he came prepared to base his candidate on “The condition of the people question,” but his audiences would listen to nothing but Republicanism and Royal Grants. At the next election, when he introduced these topics, he was told to confine himself to matters that really affected the worker. The agitation that brought about this change was almost entirely carried on by men whose presence in the movement was due, directly or indirectly, to the fact that William Morris and Walter Crane were avowed Socialists. To the outside world these names gave a guarantee that the movement they advocated so passionately was one of serious importance; in the Socialist Party they constituted a spiritual element which attracted many who were uncharmed by the promises of economists and politicians. Morris and Crane brought the teaching of Ruskin to the worker in their own lives and works as well as in their words: they put an edge on the demand for political and economic freedom.

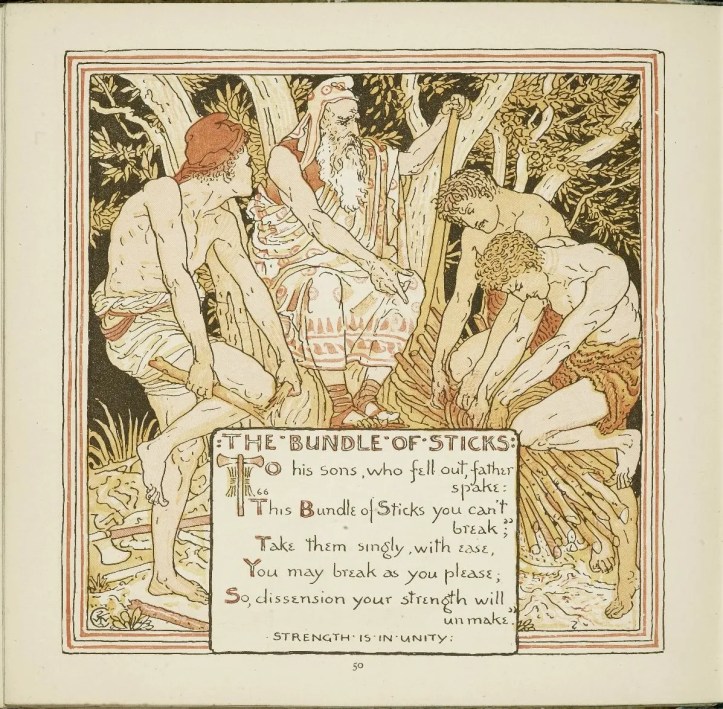

Walter Crane was born in 1845 of a family of artists, and in 1859 was articled to W.J. Linton as a wood engraver. Besides being the best wood engraver of his day, Linton was a Socialist of 1848 and an ardent lover of liberty, whose character is reflected in his wife’s “True History of Joshua Davidson.” Ruskin was then in his prime–these were the days of “Unto this Last”–and in 1862, when Crane was out of his time, the firm of Morris & Co., which was to revolutionize the interior of the English home, had just begun its operations. Crane was fortunate enough to enter on his best work early in life owing to a meeting with Edmund Evans in 1863, which led to his wonderful series of children’s picture books, the first published about 1865. It is not too much to say that these books mark a period in popular taste, and that on some of them Walter Crane’s claim to remembrance as an artist is most surely founded. They made his name known over Europe and America, and raised the world’s estimation of British art.” His picture books were in color, but his black-and-white illustrations are almost as well-known–his Grimm has been the delight of generations of children–and he devoted much attention to the design of the decorative page, writing and illustrating poems of his own, after the example of Blake. As a painter, Crane’s earliest work–and to my mind his best and most interesting–is strongly influenced by Ford Madox Brown, whose paintings were shown in the International Exhibition of 1862, and again in a one-man show in 1865. His visit to Italy in 1871-3 gave a new and less happy direction to his art. His water-colors were always simple and delightful.

The decorative quality in Crane’s picture books, and the freedom of design in the details of his drawings, soon attracted the attention of architects and others interested in house decoration. Very early in his career he had designed some vases for Messrs. Wedgwood, but it was not till 1873 that he began to invent and execute friezes and panels in gesso or relief, the first of his essays in domestic decoration. He had met William Morris in 1870 at the house of the late Earl of Carlisle, then Mr. George. Howard. Mr. Howard was keenly interested in English art and artists, and had got Philip Webb to build him a house to be decorated by William Morris, 1, Palace Green, Kensington. Crane’s work, however much in sympathy with that of Morris, was entirely unconnected with him in a business way, with one or two exceptions. His wallpapers, for example, were designed from the first in 1875 for Messrs. Jeffrey & Co. Crane himself was welcomed as a younger man in sympathy with their aims and methods by the three friends–Morris, Webb, and Burne-Jones–though he never quite shared the almost sacred intimacy which long daily association had brought about among them. It was by Mr. Howard that Crane was brought into close touch with Burne-Jones, and they worked together on a set of panels, showing the story of Cupid and Psyche, in his house. Crane often used to tell the story of Burne-Jones–so super-refined in his work–pretending to ape the tricks of the “British workman” and broadly hinting at cigars and liquid refreshment when his “employer”–Mr. Howard–came into the room where they were painting. A design by Crane—the Goose Girl–was used by Morris for his first figure tapestry, woven in 1880.

Morris’s formal conversion to Socialism in 1882–he joined the Democratic Federation in January, 1883–was the next great influence on Crane’s life. It happened at a time when he had become discontented with the conditions under which art existed, with the relations of art and life. During ’83 and ’84 Crane was again in Italy, but when he returned the perusal of “Art and Socialism” and a correspondence with Morris on the difficulties he felt soon converted him into an ardent adherent, and from then to the day of his death he never faltered or turned back. Socialism had brought him from the verge of pessimism, as regards human progress, to a real hope for the future of art founded on a reconstitution of society.

The next ten years or so were perhaps the most fruitful in effort of Crane’s life. Our number was so small that no one among us capable of taking any part in public life was allowed to remain idle, and a man of Crane’s activity and powers came to the front.

He was not naturally a good speaker, but his Socialist lectures, illustrated as they usually were by blackboard sketches, were always interesting from their personal note, the quaint and humorous turn of his mind. One lecture of his–I forget the official title on the Bag Baron and the Crag Baron, was particularly delightful, and the picture of him standing at the Blackboard and drawing with both hands at once will always survive in the memory of those present. His cartoons, freely contributed to “Justice,” “Commonweal,” “Labor Leader,” “Clarion,” etc., were merely a part of the services of his pencil to the cause. He was always ready to contribute a design or an illustration to any publication which seemed to require it. In one of these cartoons, “The Triumph of Labor” (1891), Crane reached the highest level of his powers in design and execution.

The unrest among artists, of which something has been said, came to a head in the early “Eighties, and divided into two main currents of discontent–dissatisfaction with the Academy as the representative of English art, and dissatisfaction with conditions which tended to make sound art impossible. The latter began to center round The Art Workers’ Guild, founded in 1884, a body of art-workers with which Morris and Crane soon associated themselves. An attempt in 1886 to unite all sections of artists in an open exhibition failed, but it had the very important result of bringing about the formation of The Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, of which Crane was the first president, and to which he rendered invaluable service.

The machine industry of the nineteenth century had brought about a state of things in which the artistic element was necessarily eliminated from manufactured goods, even when a conscious effort to obtain beauty in them was made. This had a double cause: the divorce of the designer from the craftsman and his material, so that he lost the inspiration which the accidents of the material affords, and evaded its restraints; and the divorce of the producer from the user, which freed him from another set of restraints no less important and useful. Morris’s lifework in art was the restoration of these fundamental conditions, the subjection, even the elimination, of the machine element in decorative arts and crafts; and The Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society took up his work on a wider scale when he had created a public for it, and carried it on with conspicuous success. Their exhibitions put designers and executants in the same position as other artists, and gave an opportunity of personal distinction for artistic work in design and craftsmanship. They have vindicated English art at home and abroad, and the success of the Retrospective Exhibition at Ghent two years ago, repeated at Paris last year, was a striking proof of the soundness of the principles by which it was animated.

Crane’s direction of the arts and crafts movement, his constant insistence on the vulgarizing influence of the machine industry in any decorative work however well-intentioned, was perhaps the greatest public service of his life. As a writer and a poet his influence was confined to a limited circle, and his various tenures of office as the head of art schools in Manchester, Reading, and London had little lasting effect. The real value of his life-work lay in this–that being a man who could, and did, produce beautiful things, he was able to claim the attention of the world at large when he expounded the conditions under which great art could exist, that sound art is only possible in sound conditions of life for artist and public alike.

Young Socialist’s Magazine was the journal of the original Young People’s Socialist League and grew of of the Socialist Sunday School Movement, with its audience being children rather than the ‘young adults’ of later Socialist youth groups. Beginning in 1908 as The Little Socialist Magazine. In 1911 it changed to The Young Socialists’ Magazine and its audience skewed older. By the time of the entry into World War One, the Y.P.S.L.’s, then led by future Communists like Oliver Carlson and Martin Abern, had a strong Left Wing, creating a fractious internal life and infrequent publication, ceasing entirely in 1920.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/youngsocialist/v10n03-mar-1916_Young%20Socialists.pdf