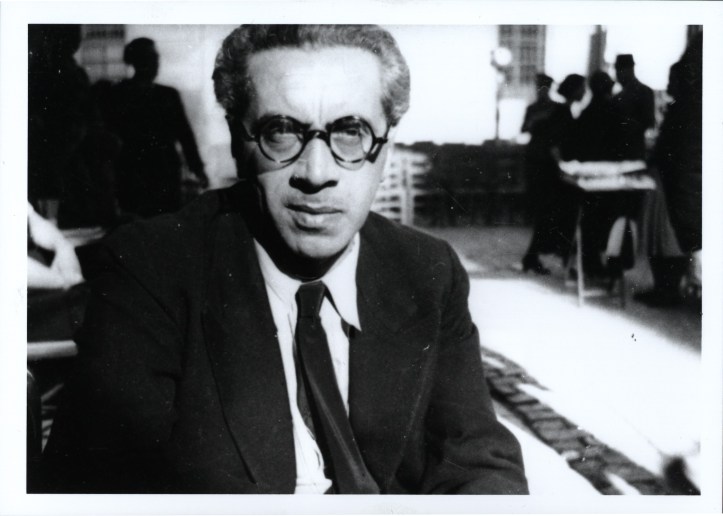

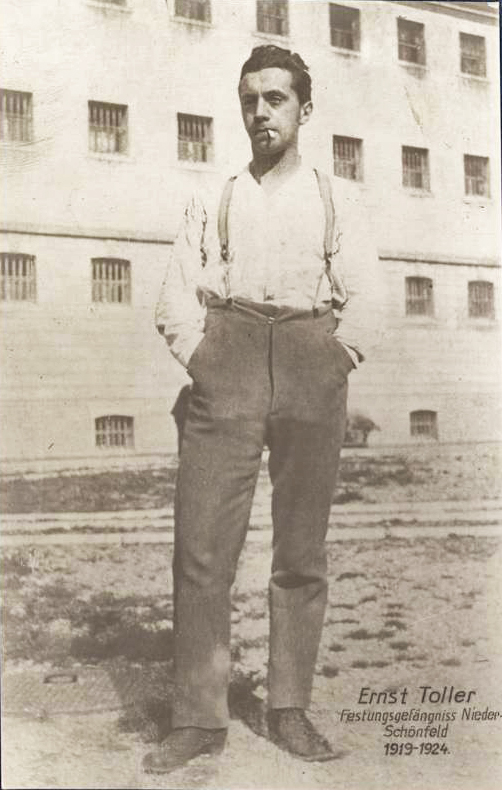

Powerful words on resisting reaction from the poet-leader of 1919’s short-lived Bavarian Socialist Republic, the expressionist writer Ernst Toller, here an exile from German fascism. Coming to the U.S. in 1936, Toller would take his life in May, 1939.

‘We Are Plowmen’ by Ernst Toller from New Masses. Vol. 21 No. 5. October 27, 1935.

A famous German playwright, now in this country, tells why he feels that the place of the writer today is in the ranks of the anti-fascist front

PEOPLE coming from the Continent to England note the strange fact that, though this island is separated from the Continent only by a narrow channel, the spiritual distance is indeed an invisible Atlantic. While Europe is struggling with social and spiritual problems, this country seems to live in a state of almost undisturbed calm. Going through the streets of London, reading the papers, visiting the overcrowded theatres and cinemas, speaking with the man in the street, one gets the impression that the problems of our time have not yet become problems for the English.

But this is only on the surface. Looking deeper, one finds a great number of people seized by a kind of restlessness that is especially evident in the young writers whose status animi I should like to express with the words: they are marking time.

The great ideals of mankind were misused. and became political play pennies in the hands of the ruling powers. They lost their value when the play was over.

The dictators, too, enemies of freedom and justice, of truth and peace, made use of those words, falsified their meaning, confused simple minds. Disgusted by this spiritual dishonesty and not knowing where to turn, many young writers preferred to “mark time.” Others again sought refuge in sectarian groups and looked there for a drug; as the world frightened them they mail-clad their fear with dogmas.

Very few are knowing or brave enough to resist the chaos of our time. Few know the way that leads to a new mankind. Man in his individual existence as a spiritual and self-responsible being is threatened. Only he who is strong, only he who has a clear knowledge of society and her possibilities is immune.

Simple-minded Marxist doctrinaires forgot the dialectic, reciprocal effect between economic forces and the will-power of man; contrary to Marx they underestimated the important effect of the word. The intellect became something doubtful: in order to lower a man one said of him, “He is an ‘intellectual.'”

The word is full of life like a tree. It roots deep in the centuries and is laden with emotional values, with the dreams and hopes, with the curses and the hatred of mankind. He who finds the right word in the right moment raises its value in a hardly conceivable degree. But the word does not serve two masters at the same time. Dangerous is the far-spread belief that one knocks the weapon out of the enemy’s hand if one takes over his words; dangerous, indeed, because words have a strange life of their own. They are bound to traditions and classes, create certain reflexes and reactions, their old contents are laden with a kind of concrete force which does not alter its direction, if one tries to substitute cunningly new contents.

When in Germany the Left started to take over the nationalistic slogans of the adversaries, those slogans did not lose anything of their disastrous effect; often they became the bridge on which our followers went over to the enemy.

In order to get a clear picture of the material and spiritual reality, one must have the courage to grip the sense of things in their being and their growing. He who only sees the symptoms cannot master them and because he cannot master them, he is driven to overlook them.

THE OTHER DAY I had the honor to preside over a discussion in which four English writers spoke on the tasks of literature. One speaker turned against that literature that pictures the misery of men, expresses their social problems. She gave praise to those authors who dwelt on the beauty of nature. Only that writer, she said, can today speak to the oppressed man, who roots deep in the earth and receives his strength from the soil. But on earth there are not only trees, flowers, grass. On earth grow men with their problems and their needs. and their despair. When last year I came into the Rhondda Valley in South Wales, where thousands had been jobless for years, I asked a little boy: “What would you like best?” And the child answered: “I only wished I could just once eat up a whole penny onion pie by myself.”

That writer should have looked into the eyes of this child.

NO, NOBODY can escape the struggle of the present, especially in a time when fascism has made the theory of the totalitarian state an iron law. The dictator asks of the writer to be the obedient megaphone of ruling opinion. This demand of the dictators has, however, one good side: it leads us back to our own true self, it makes us estimate values anew which, because often misused, have been underestimated by us. Only he who has lost freedom is able to value it truly. Freedom and self-responsibility make self-responsibility make the dignity of the individual.

We Marxists are often accused of wanting to suppress the individual. But the contrary is true. In this society only a few people can become individuals. The individual exists as little today as the nation exists. Only when the nation in all her citizens can freely develop, will her true life begin. Only when the great national works of culture become a common possession, will her mission be fulfilled.

We won’t be troubled by the madness of nationalism. It is nothing but the death-rattle of a dying order. Nationalism dies and the nations awake. With them that individualism awakes that receives its strength from society and gives its strength to society. Our internationalism is the harmony of individuals, peoples, and nations who have been freed to turn to the great tasks which make life worth living.

Let us work incessantly, let us not be confused by the criticisms of the adversaries who say that our works are not “beautiful.” Ego sumus Arcadia–we too love beauty, the blue seas and the vast horizons, the stars and the tides. But as long as society is shaken by tragedies which are unnecessary (because they are brought about by an unjust social system) we will not cease to denounce the senselessness of such tragedies.

We do not love politics for its own sake. We take part in the political life of today, but we believe that not the least important meaning of our fights is to free a future mankind from the shallow fight of interests which today is called “politics.” We know the limits of our work. We are plowmen and we do not know whether we will be harvesters. But we have learned that “fate” is nothing but an evasion. We ourselves create fate. We want to be true and courageous and human.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1936/v21n05-oct-27-1936-NM.pdf