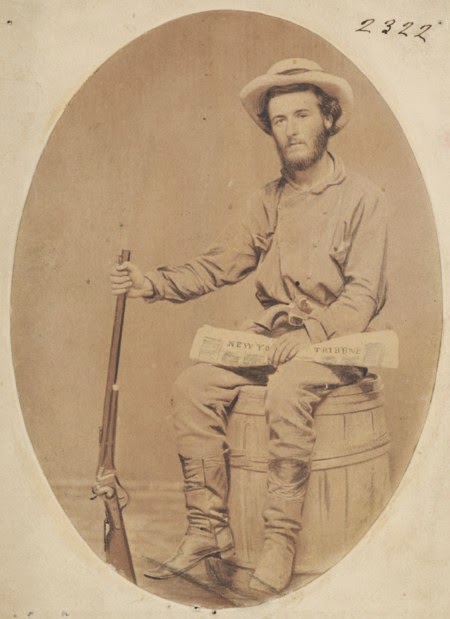

John Brown remains a person of immense substance and continuing consequence more that 160 years since his martyr’s death. The account below was written while Brown was still alive, n the period between the Harper’s Ferry raid and his execution. A radical abolitionist, a radical in general, the Scottish-born James Redpath was a journalist for the New York Tribune at the same time as Marx. Brown’s companion in Kansas, and as this article also shows–his publicist, Redpath was later a lobbyist for the Republic of Haiti, whose writings did much valuable work for the cause.

‘The Kansas Work of John Brown’ by James Redpath from The Anti-Slavery Bugle. Vol. 15 No. 12. November 5, 1859.

Old Brown–John Brown–the chief and originator of the insurrection, was a man of sixty-five years of age. He was born, I believe, in Connecticut, resided, for a considerable period of his life, in Massachusetts; but for some time–perhaps for several years–had lived in the State of New York, somewhere in the vicinity of Utica.. When the Kansas troubles broke out he had a wife, seven sons and a daughter living. What are left of his family still live on his farm near Utica. At Springfield, I believe, he was engaged in the wool trade. Wherever he lived he soon acquired the reputation of a man of the sternest integrity of character. In Kansas he was the great living test of principle in our politicians. The more corrupt the man, the more he denounced Old Brown. It was a true compliment to be praised or to be recognized by him as a friend; for, even in his social dealings, he would have no connection with any man of unprincipled or unworthy character. In his camp he permitted no profanity; no man of loose morals was permitted to stay there–unless, indeed, as prisoners of war. “I would rather have the small pox, yellow fever, and cholera, all together, in my camp, than a man without principle.” This he said to the present writer, when speaking of some ruffianly recruits whom a well-known leader had recently introduced. “It’s a mistake, sir,” he continued, “that our people make, when they think that bullies are the best fighters, or that they are the fit men to oppose these southerners. Give me men of good principles–God-fearing men–men who respect themselves, and with a dozen of them I will oppose any hundred such men as these Buford ruffians.” His whole character is portrayed in these words. He was a Puritan in the Cromwellian sense of the word. He trusted in God, and kept his powder dry. Prayers were rendered up, in his camp, every morning and evening, no food was eaten, unless grace was first asked on it.

For thirty years he secretly cherished the idea of being the leader to a servile insurrection: the American Moses, predestined by Omnipotence to lead the servile nation in our Southern States to freedom: if necessary, through the red sea of a civil war, or a fierce war of races. It was no “mad idea” “concocted at a fair in Ohio,” but a mighty purpose, born of religious convictions, which he nourished in his heart for half a life-time.

When the horizon of freedom looked gloomy in Kansas, he took leave of his wife and younger children, and, with several of his sons–four or five of them–went out to Kansas. He thought that the hour was approaching for his work to begin. The ballot box had already been desecrated; the ruffians of Missouri had overwhelmed by violence the rights of the North. He went to put a stop to the insolence and violence of the South; and to him, more than any other living man, we owe it that Kansas is a Free State to-day. To a man of a very different character, Gen. Lane, although a personal and malignant enemy of mine, I would accord the second place in this honorable rank.

Brown was not sent by any one, unless by God, (as he himself believed,) to vindicate the rights of the North and of freedom in Kansas. He was no politician. He despised the class with all the energy of his earnest and determined nature. His first appearance in the Territory was at Osawatomie, at a public meeting at which accommodating politicians were carefully pruning a set of resolutions to suit every shade of Free-State men. The motion that called him out was to pass a resolution in favor of excluding all negroes from Kansas. Old Brown arose, and scattered consternation among the politicians by asserting the manhood of the negro race, and expressing his earnest Anti-slavery convictions with a force and vehemence little likely to please the hybrids then known as Free-State Democrats. There were a number of Indiana Democrats present, whom his speech so shocked that they subsequently became, and remained, I believe, in the class of “law-en- order-abidin” Pro-Slavery men. It was his first and last appearance in a public meeting. Like most men of action, he underrated discussion. He secretly despised even the ablest Anti-Slavery orators. “Talk is a national institution, but it does no good for the slave.” He thought it an excuse very well adapted for weak men with tender consciences. Most men, who were afraid to fight, and too honest to be silent, deceived themselves that they discharged their duties to the slave by denouncing in fiery words the oppressor. His ideas of duty were far different; the slave, in his eyes, were prisoners of war; their tyrants, he held, had taken up the sword, and must perish by it.

The next time he appeared among men assembled in numbers was when Lawrence was surrounded by sheriff Jones’ posse comitatus, (from Missouri,) during the Governorship of Shannon, in the month of December, 1855. His eldest son, John, had command of a large company of men, and he himself had charge of a dozen. He was dissatisfied with the conduct of Robinson and Lane, and predicted that their celebrated treaty, with its diplomatic phraseology, would only postpone the discussion at arms, which was inevitably and rapidly approaching. Lane sent for him to a Council of War, “Tell the General,” Brown said, “that when he wants me to fight, to say so; but that is the only order I will obey.” In disobedience to general orders, he even went out of camp with his dozen men to meet the invaders–to “draw a little more blood,” as he phrased it–but by the special messenger of Lane he was induced to forego this intention and return. He always regretted doing so, and maintained that if the conflict had been brought on at that time a great deal of bloodshed would have been spared.

As to John Brown’s political opinions. It is asserted that he was a member of the Republican party. It is false. He despised the Republican party. Of course he was opposed to the extension of slavery; and in favor, also, of organized political action against it. But when the Republicans cried, Halt; John Brown said–FORWARD, march! He was an Abolitionist of the Bunker Hill school. He had as little sympathy with Garrison as Seward. He believed in human brotherhood and in the God of Battles; be admired Nat Turner as well as George Washington. He could not see that it was heroic to fight against a petty tax on tea, and endure seven years of warfare for a political right, and a crime to fight in favor of restoring an outraged race to every birthright with which their Maker has endowed them, but of which the South has for two centuries robbed them. The recent outbreak was premature. The inevitable coming triumph of the Republican party, I have the best authority for stating, was the most powerful reason for the precipitate movement. The old man distrusted the Republican leaders: he said that their success would be a backward movement to the anti-slavery enterprise. His reason was that the masses of the people had confidence in these leaders; and believe that by their notion they would ultimately and peacefully abolish slavery. That the people would be deceived, that the Republicans would become as conservative of slavery as the Democrats themselves, he sincerely–may I add, and with reason–believed? Apathy to the welfare of the slave would follow, hence it was necessary to strike a blow at once. You know the result.

PDF of full issue: https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn83035487/1859-11-05/ed-1/?sp=1&st=image#viewer-pdf-wrapper