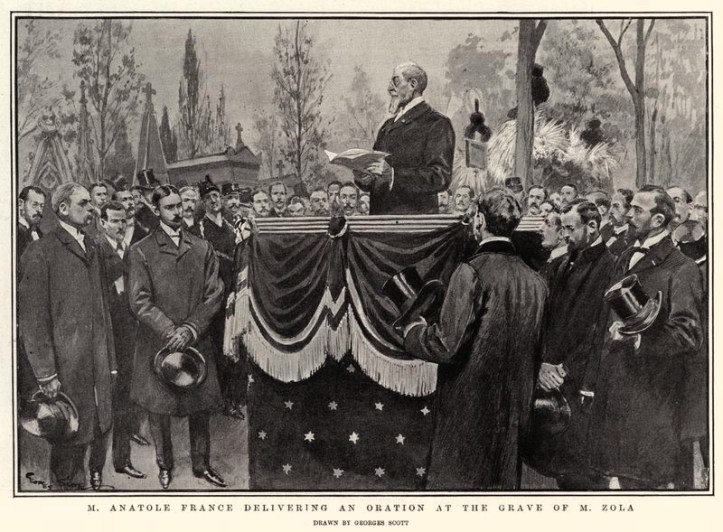

Along with France’s duly famous eulogy for Emile Zola at Montmartre Cemetery, included below is a letter read to a gathering of the League for the Rights of Man held in Zola’s honor two years later.

‘Oration Delivered at the Funeral of Emile Zola’ (1902) by Anatole France from International Literature. No. 7. 1940.

Montmartre Cemetery, October 5, 1902.

Messieurs, having been requested by the friends of Emile Zola to say a few words over his grave, I first wish to pay my respects and condolences to the lady who for forty years was the companion of his life, who had shared and assuaged the fatigues of his early career, who enlivened the days of his glory, and who sustained him by her untiring devotion in his hours of agitation and suffering.

Messieurs, in rendering to Emile Zola, in the name of his friends, the honor which is his due, I shall not give voice to my pain and to theirs. It is not by plaints and lamentations that we should honor those who have left a great memory behind them, but by sturdy praise and a Sincere picture of their work and their lives.

The literary work of Zola is immense. You have just heard the President of the Writers’ Society describe its character with admirable precision. You have heard the Minister of Public Education expatiate on its intellectual and moral significance. Permit me, for a moment, to dwell upon it in my turn.

Messieurs, when we saw this work being erected stone by stone, it was with surprise that we measured its grandeur. Some admired it, others were astonished at it; some praised it, others blamed it. Praise and blame were equally vehement. This powerful writer was sometimes reproached sincerely, yet unjustly (I know it, for I did so myself). Invective was mingled with eulogy. Yet his work went on developing.

Today, when we descry the colossal form in its entirety, we also recognize the spirit with which it is imbued. It is the spirit of goodness. Zola was good. He had the grandeur and the simplicity of great souls. He was profoundly moral. He painted vice with a rude but virtuous hand. His apparent pessimism, the somber humor with which so many of his pages are tinged, but ill concealed a genuine optimism, an obdurate faith in the progress of intelligence and justice. In his novels, which are social studies, he censured with a vigorous detestation a society of idleness and frivolity and a base and pernicious aristocracy, and he combated the evil of our times: the power of money. He was a democrat, but he never flattered the people, and he endeavored to bring them to realize the bondage of ignorance, the dangers of alcohol, which rendered them imbecile and turned into helpless victims of every oppression, of every misery and of every shame. He combated social evil wherever he encountered it. Such were his hatreds. In his last books he displayed his fervid love of humanity in all its fullness. He made the effort to divine and predict a better society.

He wanted an ever larger number of men to enjoy the fruits of happiness on this earth. He placed his hopes in thought and science. He expected from the new force, machinery, the progressive emancipation of laboring humanity.

This sincere realist was an ardent idealist. His work is comparable in grandeur only to that of Tolstoy. They are two vast idealistic cities raised by the muse at two extremes of European thought. Both are generous and pacific. But Tolstoy’s is the city of resignation, Zola’s is the city of labor.

Zola won fame when he was still a young man. Tranquil and celebrated, he was enjoying the fruits of his labors, when he suddenly tore himself from his repose, from the work he loved, from the peaceful joys of his life. The words we pronounce over a coffin should be grave and serene; we should betray nothing but calm and harmony. But you know, Messieurs, that there is no calm but in justice, and no repose but in truth. It is not of philosophical truth, the object of our eternal disputes, I am speaking, but of that moral truth which we can all grasp because it is relative, tangible, conformable to our nature, and so near to us that an infant may touch it with its hand. I will not betray justice, which bids me praise that which is praiseworthy. I will not conceal the truth by craven silence. And why should we be silent? Are they silent who calumniated him? Over this bier I will say only what should be said, and I will say all that should be said.

Before recalling the fight that Zola waged for justice and truth, can I remain silent about those who were determined to encompass the ruin of an innocent man, and who, knowing that if he were saved they would be lost, attacked him with the brazen audacity that is born of fear? How can I keep them from your sight when it is my duty to show you Zola rising, feeble and unarmed, against them? Can I be silent as to their lies? That would be to conceal his heroic rectitude. Can I be silent as to their crimes? That would be to conceal his virtue. Can I be silent as to the outrages and the calumnies they heaped upon him? That would be to conceal his recompense and his honors. Can I be silent as to their shame? That would be to conceal his glory. No, I shall speak!

With that calmness and firmness which the spectacle of death lends us, I will recall those dark days when selfishness and fear held their seats in the councils of government. The iniquity was becoming known, but one felt that it was being sustained and defended by public and secret forces so powerful, that even the staunchest hesitated. Those whose duty it was to speak, held their peace. The best of them, who did not fear for themselves, feared, however, to plunge their party into frightful dangers. Deceived by monstrous lies, excited by odious exhortations, the mass of the people were infuriated, for they believed themselves betrayed. The masters of public opinion all too frequently accepted the error which they despaired of destroying. The shadows thickened. A sinister silence reigned. And it was at this moment that Zola wrote to the President of the Republic that measured and terrible letter in which he denounced chicanery and perjury.

With what fury he was then assailed by the criminals and by their interested protectors and involuntary accomplices, by the coalition of all the reactionary parties and by the deceived crowd! You have witnessed that yourselves, and you know of many an innocent soul who in saintly simplicity joined the hideous cortege of his hired vilifiers. You have heard the howls of rage and the savage calls for his death, which pursued him even in the Palais de Justice itself, and throughout that long trial, which judged in deliberate ignorance of the case, on the testimony of false witnesses, and amid the rattling of sabers.

I see here among us several of those who stood faithfully by his side in those days and shared his perils. Let them say whether greater outrages were ever inflicted on the just! And let them tell us of the firmness with which he bore them. Let them tell us whether his robust goodness, his manly pity, and his mildness ever forsook him, or whether his constancy was ever shaken.

In those villainous days many a good citizen despaired of the welfare of his country, of the moral fortune of France. It was not only the republican defenders of the regime who were crushed. Even one of the most resolute enemies of that regime, an irreconcilable Socialist, was heard to exclaim in bitterness: “If this society is so corrupt, then even its ruins will be too infamous to serve as a foundation for a new society!” Justice, honor, thought—all seemed lost.

But all was saved. Zola not only exposed a judicial error; he denounced a conspiracy of all the forces of violence and oppression that had united to kill social justice, the republican idea and free thought in France. France was aroused by the courage of his words.

The consequences of his act are incalculable. They are unfolding today with a potent force and majesty; they stretch on endlessly; they have started a movement for social equity which nothing can halt. They are giving rise to a new order of things, founded on better justice and a deeper knowledge of the rights of all.

Messieurs, there is but one country in the world in which these great things could have come to pass. How admirable is the genius of our country! How beautiful is the soul of France which in past centuries taught the rights of man to Europe and to the world! France is the country of embellished reason and benevolent thought, the land of just magistrates and humane philosophers, the land of Turgot, Montesquieu, Voltaire and Malesherbes. Zola has deserved well of his country in not despairing of justice in France.

Let us not pity him for having endured and suffered. Let us rather envy him. Elevated on the most prodigious pile of outrage that folly, ignorance and iniquity have ever erected, his glory has attained to heights inaccessible.

Let us envy him: he has honored his country and the world with an immense work and a great deed. Let us envy him: his destiny and his heart have earned him the greatest of fortunes: he was the conscience of humanity at that moment.

Letter Read at a Meeting in Memory of Emile Zola October 1, 1904.

Mr. President,

I deeply regret that I am unable to attend the grand meeting arranged by the League for the Rights of Man. I would have joined you in acclaiming to the best of my ability the name of Emile Zola. He was a man of energetic labors and of great deeds. As a novelist, his work is immense. I may express the admiration he inspires as a writer, without being suspected of complaisance, for if at first I combated with less restraint than sincerity certain rude manifestations of his genius, in many an article I recognized the power and goodness of his literary work long before those days of struggle when I ranged myself on his side.

In an instant, that man of thought became a man of action. When he wrote his letter, J’ accuse…!, he performed a revolutionary act whose potency is incalculable, and whose beneficent results have never ceased to manifest themselves in our moral and political life, and make their influence felt even in foreign countries.

His courage and his rectitude brought him to the forefront in that. small group of men who fought. for justice in those infamous days: Scheurer-Kestner, Grimaux, Duclaux, Gasten Paris and Trarieux, who have died in battle. And others, too, who have survived and rise in our memories: as Ranc, Jaurés, Clémenceau, Séailles, Paul Meyer, that noble Picquart, and Louis Havet, whose honest and staunch words you will hear today, and you, Francis de Pressensé, whom our friends Quillard and Mirbeau saw calm, firm and tranquil beneath the shower of abuse and blows in Toulouse and Avignon where the White Terror raged.

That was the time when, amid the peaceful solemnity of a prize distribution, in the presence of high generals of the French army, the Dominican monk Didon exhorted the military chiefs to depose a pusillanimous government and excited the Catholic youth to massacre in the streets those proud intellectuals who could not tolerate injustice in silence! It was the time when the Minister of War, Cavaignac, informed his colleagues of his scheme to try in the High Court, on the charge of high treason, all those who had defended Dreyfus, even his lawyers, Demange and Labori!

You will agree that it is with a certain feeling of joy and pride that one remembers that one had such adversaries as these.

All you who suffered contempt and who bore the name of Dreyfusites with pride must be just and admit that you owe a lot to your enemies.

Yours has been a strange and glorious destiny, that, seeking at first to secure the reparation of an error of justice due to a handful of unscrupulous perjurers, you gradually saw all the forces of reaction and oppression rise against you, and that your courage grew as in grandeur with the growth of the task. Your task grew more formidable.

That task is not yet accomplished. You have struck a deadly blow at the false plea of interests of state, at the abuse of public power, at the abominable practice of secret trial. But is it not an infamy that military tribunals still exist after so many vile conspiracies and SO many monstrous arrests?

A great deal remains to be done. But let us not lose courage. The Dreyfus affair rendered our country the inestimable service of bringing openly face to face the forces of the past and the forces of the future, bourgeois authoritarianism and Catholic theocracy, on one side, and Socialism and free thought, on the other. The ultimate victory of organized democracy is beyond doubt. Let us render to Emile Zola the honor that is due him for having courageously flung himself into the perilous fight and for having shown us the way.

It was six years ago that we saw Zola’s life threatened by an ignorant crowd seduced by criminals, as he left the Palais de Justice. The Municipal Council of Paris, recaptured by the Republicans and the Socialists, will perform an act of reparation in renaming the Boulevard du Palais as the Boulevard Emile Zola.

Literature of the World Revolution/International Literature was the journal of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers, founded in 1927, that began publishing in the aftermath of 1931’s international conference of revolutionary writers held in Kharkov, Ukraine. Produced in Moscow in Russian, German, English, and French, the name changed to International Literature in 1932. In 1935 and the Popular Front, the Writers for the Defense of Culture became the sponsoring organization. It published until 1945 and hosted the most important Communist writers and critics of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/literature/international-literature/1940-n07-IL.pdf