Wherever there are great profits, there is also terrible exploitation. A miner takes us on a tour of hell, above and below ground, in Butte, Montana.

‘Butte–Montana’s Hell’ by a Miner from Industrial Worker. Vol. 4 No. 31. October 24, 1912.

Being in search of a master, and having considerable enforced leisure time, I thought it opportune to let the outside world know something of the conditions that obtain here in Butte, Montana.

I am of the opinion that the workers on the outside are laboring under a delusion concerning working conditions in this camp. Butte has been word painted by Boosters’ Clubs, the Chamber of Commerce (very impressive and dignified names for modern parasites, are they not?), real estate sharks who rent and sell so-called homes on the installment plan to the mine workers, who never live long enough, or get work steady enough to pay for one and often, as was the case in the latter part of 1907, and the fore part of 1908, when some twelve or fifteen thousand miners were compelled to leave Butte due to the panic, and the subsequent closing down of the mines, lose practically all they have invested, and the usual herd of bloodsuckers infesting every industrial center, as being the most prosperous and best organized town in the country.

The above mentioned dignified body, the Chamber of Commerce, at the head of a big brass band, (brass, and then some more brass, lots of brass, then again some more brass–if you want a good chamber of commerce) and a special train has just returned from visiting sister states, its mission being to tell our unwily neighbors, and pound it into them by the aid of the above-mentioned brass, of our great prosperity.

I have before me three files of the Butte Intermountain, the local corporation mouthpiece, covering mining reports for 1912, which are extracts from leading mining and engineering journals, which speaks in unmistakable terms of Butte’s great prosperity, as far as a few well-kept be-ladies of New York are concerned. And I herewith submit a part of the reports, and when it is considered that the gigantic dividends stated in these reports, go to a few absentee stockholding industrial lords who live in New York, Boston and Paris, and to whom property has become an impersonal proposition, it is easily seen that Butte’s much-vaunted prosperity exists for others than the great mass of toiling mine workers who produce the great wealth mentioned in these reports.

A part of one of the reports follows: “The achievements of present day dividend-paying American mines and works–no less than the payment of over $700,000,000 to holders of stocks, is a record which few industries have made.” And bear in mind, too, that this only refers to the 103 companies paying dividends during the present year and has no reference to other companies which have paid millions to shareholders, but prior to 1912. Through reports made to the Chicago Mining and Engineering World by the above-mentioned 103 companies, dividends have been paid during the first five months of 1912 totaling $33,839, 369.11.

Another report states that during the first seven months of the present year 124 American mines and metallurgical works, according to the figures compiled by the Mining and Engineering World, participated in dividend disbursements totaling $53,167,685, which with the $10,821,025 disbursed by the securities-holding corporations, brings the total for the period to $63,745,511. Since incorporation, the 124 companies and the nine securities-holding corporations contributing to the above have divided among shareholders no less than $895,787,610, the former being credited with $751,705,090, and the latter $144,082,520, a return on the former of 110 per cent and the latter 70 per cent.” Seventy and one hundred per cent is certainly something of a dividend watermelon for a nice fat, slick bunch of corporation labor-squeezers to cut. But if you think this is a dandy, and are about to rush to your brokers, (yes, brokers) to get a slice of this very toothsome product of the cucumber family, wait until you have perused the following, which is a report of some two months ago. “When 111 American mining and metallurgical companies can pay dividends totaling $730,592,965, it is indisputable evidence that extraordinary profit can be made in legitimate mining operations.” (The thought presents its self to one’s mind that if the water was squeezed out of these mining operations there would be little left that was legitimate.)

“There is little cause to wonder why Investors take kindly to “going” copper stocks when, from reports made to Mining and Engineering World, it is learned that 22 companies, all but two operating in the United States, have so far this year paid to share-holders $18,128,373. Since incorporation however, these 22 properties have yielded profits in the shape of dividends totaling $350,289,697, which calculated on the per cent outstanding share capital of $220,170,502, is equivalent to 159 per cent.” Leading among the coppers this year is Anaconda with a credit during the present year of $4, 276,250 and $63,548,750 since incorporation.” This company is the big squeeze that holds within their economic grasp, many thousands of mining slaves of Butte, and over which they cracked the economic whip and stampeded the miners down the hill to win a municipal election in April of this year.

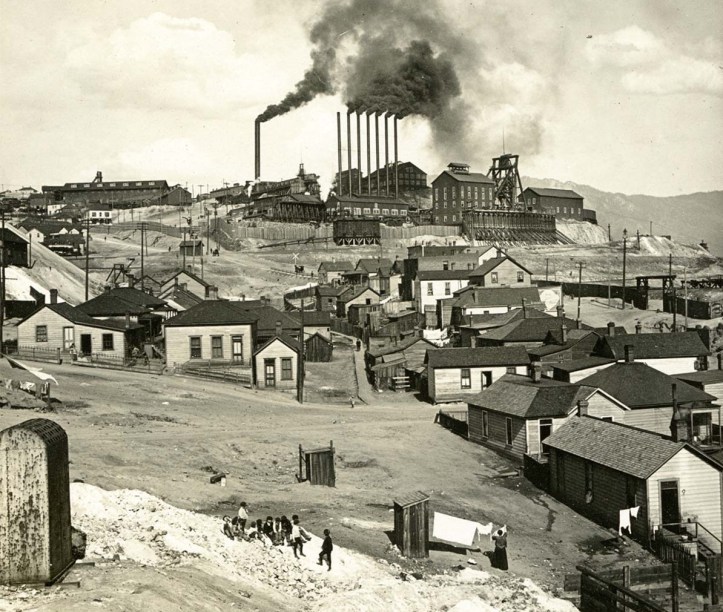

The report goes on to state that some of the companies dividends run up to as high as 224 per cent, 67 per cent being the lowest that any of them paid. These figures are important, as a large portion of the wealth represented by them comes from this camp. Butte produces two-thirds of the world’s supply of copper, and yet the pale-faced, emaciated consumptive miners who produce this vast aggregation of wealth are practically homeless.

Two incidents will serve to show how much prosperity is enjoyed by the actual resident of Butte. Not long since, I attended an open air street meeting. The speaker wanting to illustrate a certain point, asked how many owned their own homes. One man out of an audience of about 500 answered in the affirmative. Again I have before me an issue of the local press of the fore part of this year containing a glowing editorial of the “Governors’ Special,” with several governors of we torn states aboard, traveling in the eastern states telling the people of the east what wonderful opportunities and great advantages waited them in the golden west, particularly Montana. Right beside this glowing account, was an editorial telling of the great difficulties the Associated Charities of Butte, were having in trying to cope with the conditions of poverty, and stated they were unable to meet the situation and issued a call for aid.

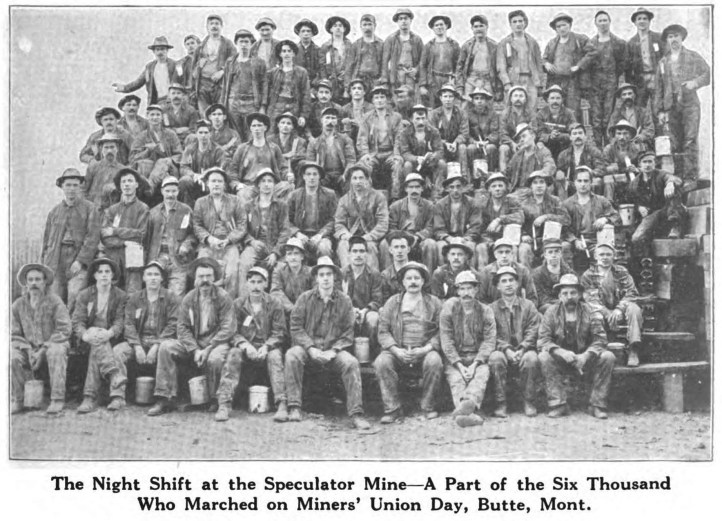

Following are some real Boosters clubs and the Brass Band gentlemen have not mentioned. When the job seekers arrive in Butte they start rustling the mines, unless they are fortunate enough to secure a letter from the company store. I have known jobless wage slaves to rustle these mines from eight to ten months steady before securing employment. There is an army of from three to five thousand of homeless and jobless job seekers, rustling on the hill every day. They line up and march past the foreman, who stands by the shaft and shakes his head at all those who are not big and husky, and haven’t letters.

It takes men with an iron will, and constitution of steel to withstand the awful strain to which the miners are subjected. Fifty per cent of these underground dungeons where the mine slaves have to work, tax their vitality to such an extent, that it is impossible for them to work over half time. This is the reason, though never given, for so many ten day men. What we mean by ten day men is men who have had their vitality sapped by these hell holes, to such an extent that it is necessary for them to rest a couple of weeks after a short time at work in order to regain their lost energy. Many men are hired every day and sent to work in stopes which they find too bad to work in, and these men turn right around and come on top without striking a lick.

These statements may seem exaggerated to one who has never experienced the hot boxes in these mines, where men have to contend with heat, ranging from 75 to 100 degrees, and you must bear in mind that this degree of heat under ground is far more unbearable than on the surface. Having worked in these holes for a period of nine years I know from actual experience whereof I speak. I have worked in some of the worst holes in these mines, and can speak with perfect knowledge of the conditions. I will therefore give some of my own experience, which is the experience of countless hundreds who have in the past, and are at the present, and will in the future be employed in these mines.

My first experience in a real hot box, was on Upon entering the stope, a very sickening, the 1,200-foot level of the Pennsylvania mine. Upon entering the stope a very sickening, nauseating feeling comes over one, due to the dense heat and the very gaseous state of the air. This feeling will wear away, to a certain extent as one starts perspiring freely, that is If one has been somewhat tempered to the place. New men coming in, if not looked after and warned how to guard themselves, are overcome and carried out.

I have wrung many quarts of perspiration from my digging shirt during a regular working shift, and if slits are not cut in the shoes one is compelled to take them off and pour the perspiration out. Many men work perfectly nude to the waist line. I have drunk several gallons of water during a shift of eight hours, and have not had occasion to answer nature’s call to urinate, for a lapse of twenty-four hours. Aside from the tortures of the dense heat, and stupor from the gases, one is often nearly suffocated with sulphide dust from the drilling machines, and dioxide gas from powder smoke so thick one could not see a light ten feet away. I have came out of the mine day after day with nose and throat clogged and highly inflamed from these sulphide dusts. Connect all these miseries with the mental worry necessarily attendant upon one working in very dangerous ground, and you have a combination of causes, that produces very serious effects upon the life and health of the miner.

My next experience was on the 2,200-foot level of the Montain Con. Here we were two thousand two hundred feet below the surface of the earth, no possible way of getting air, other than compressed air forced to us through a small two-inch pipe. This place was a veritable inferno, a human crematory. Imagine yourself in a steam bath where the atmosphere has suddenly become over-laden with hot steam and you find yourself gasping for breath before you can reach the open air, (as is often the case at some of our hot spring sanatoriums) and you will be able to form some conception of the feeling one has while working in a place of this kind. It is often the case that one feels so faint and sick, that it is impossible to eat at dinner hour.

Besides the dense heat, gas, powder smoke, and sulphide fumes, we were drenched with copper, water the entire shift. Many out of the one hundred mines operating in Butte, have their small copper water tanks under ground, into which these copper waters flow, and into which old scrap iron is placed to precipitate. Besides these small tanks under ground, the company has a long line of these tanks on the surface, and these copper waters are pumped up, and flow through these tanks again. All the old iron and tin cans that can be gathered up over the city is placed in these tanks to precipitate. When it is considered that it takes but a few days to precipitate this iron into 80 and 90 per cent copper, and the writer himself bas seen a strong stream of copper water eat a hole through a brand new mine rail in twenty-four hours, it will not require much stretch of Imagination to conceive the effects of this chemical solution on tender human flesh.

I have seen miners covered with hundreds of festering copper sores into which one could put a small pea when the black crust which forms over them has been lifted off. These sores are extremely sensitive and painful. I have in mind an Italian miner who had been a long time securing employment, and who could speak little English, and had a family back in his native land to support, who was placed in one of these copper-water hell holes, and was green and ignorant of how to guard and protect himself. The copper sores on this mine slave developed into deep seated ulcers as large around as silver dollars, and to approach near to him in the heat of the mine, after he had become heated from working, the stench from his person would turn one sick.

At the end of the first shift before becoming tempered to the place, in one of these infernos, on being hoisted to surface, and open air, I cramped so badly in every cord and muscle that I was unable to remove digging clothes for two hours. One shrinks and shrivels up in one of these crematories like a piece of fat bacon on a hot frying pan. After putting in three months in this hole, it was several months before the flesh covered the bones on the digits of the feet. The feet and hands are the most unprotected parts of the body. One must handle everything and often walk ankle deep in the copper water.

Under these conditions it is not strange that the average life of a Butte miner is only seven to eight years. Nor is it strange that over ninety per cent of Butte miners are affected with tuberculosis and other lung troubles. Nor is it strange that we are planting so many mine slaves in our cemeteries daily. (Though Butte is a young city it has already placed over 35,000 in the old cemetery and has started a new one.)

I have seen many men hoisted up from the Anaconda and St. Lawrence mines who had been kept in some Hell hole until they dropped in their tracks, overcome by fire gas. Most of the mine workers are lured here by the little higher pay, than is generally paid elsewhere, and come here in a hopeful frame of mind, few marry and before they can hope to raise a family, or purchase a home, many of them contract miners consumption and become charges on charity. Butte is very conspicuous for its absence of gray-haired men.

Miners’ Union No. 1 pays out several hundred dollars weekly to sick and injured members. The union pays to each of its members $100 sick benefits, also $100 funeral expenses, and besides these benefits several committees are out each week waiting on sick members who have absorbed the sick benefits, to which they are entitled, but have been reported in need, special donations are voted to them, and often times special assessments are voted and levied of 25 cents to $1.00 a member to help members in need. On top of this members of the union go through the mines and take up subscriptions to aid needy members. After all these sources of benefits have been absorbed they are left on the world to do as they can. So you see, after these industrial soldiers have given their very lives on the industrial field to swell the profits of monied hogs in New York and Boston they are thrown back on the workers themselves to care for.

I have on file an issue of the Butte Miner of April 1910, containing a report of a joint committee of the Business Men’s Association, and the Trades and Labor Council, which was appointed to investigate and secure data regarding the high cost of living in Butte. The committee did its work very thoroughly, and showed by an itemized account of articles, and the cost of each article, that it cost a Butte miner with a family of four or five $96 a month to live. How many homes would Butte miners buy with the salary left?

After men meeting with fatal accidents the company exonerates itself through their company owned coroner, mining-Inspector-intimidated brother miners who act as witnesses for them and upon the coroner’s jury. When one of the workers is injured the ‘Boss’ is sent around to feel out the men and out who would and would not make good witnesses for them. Those who are favorable to the company are subpoenaed. Practically all of the accidents in these mines are declared by these company owned coroners to be unavoidable. Many of these men who ruined their lives saving company property now eke out a precarious existence around the saloons.

Most of the Butte miners seem to be under the hypnotic influence of crooked labor leaders, and it is very persistently rumored that some of these so-called leaders draw two salaries, one from their organization and one from the company. The Butte unions are governed by A.F. of L. ideas which have been dead among all intelligent and honest working men for twenty-five years. These ideas are still wet nursed by the labor fakirs, politicians, and hundreds of degenerated stool pigeons which the company has to keep in the unions, and on the street corners to create and report the sentiment.

The male population of Butte, I think I will be safe in saying is about eight to one of the fair sex. Of course this necessitates the maintenance of a large restricted district. (For it is not good that single men should live alone.) And Butte has, until the present administration for many years past, paid many thousands of dollars of its current expenses each year from the money earned by the debauchery of American womanhood who have been forced to this life by the same economic conditions that have forced the sexes apart.

And this is a Christian city, where it cost $40 to secure the services of one dressed in the mental livery of the sycophant to say mummery, (called high mass) over ones dead friend with 40 churches, nearly three hundred saloons, a chamber of commerce and a booster club.

Speaking from a psychological point of view, if men’s ideas do not fall from space (or emanate from God–a mental phantasm); if they Issue out of that with which the mentality comes in contact, out of the conditions, and environment with which they are surrounded, and upon which the mentality acts, and reacts; it seems to me that in a city hemmed in by four gigantic, dark granite walls, beyond which one can not see; in a city so thickly studded with black belching smoke stacks, gallows frames, unsightly dumps, and great ash heaps, which present more the appearance of a burnt, black dismal forest than a modern city, the sight of which, in connection with the thought of all the suffering and miseries contained within gives one the shudders like those following a childhood’s night mare; in a city dismal, bleak and barren of all natures beauties; in a city without lawns; in a city whore one never inhales the fragrant perfumes wafted from the petaled lips of beautiful flowers; in a city without loves encircling vines, without sylvan beauty, beneath the shade of which one could sit in pleasant reverie and listen to the murmur of the gentle breeze as it wended its way through the branches, as I have often done in years gone by; in a city without the cheering chirp or melodious song of a single bird in a city where many thousands exist, but where not a single soul really lives; in a city very rich in the products humanity needs, but positively destitute of one life that lives; in a city where thousands toil in dungeons black, whose lives are but an ashen vapor, an empty dream, merely a bubble, arising upon the dividing line of the waves of two great eternities, glistening in all its constituent phases, quivering for a single moment in its helplessness while being tossed about on the waves of social dynamics of which it is unconscious, bursting, and going out again, disappearing as if by magic, like a flake upon the waters, there is but one idea that can eventually issue from these conditions, and that can be stated in one word, REVOLUTION.

Arise, arise, ye sodden slaves,

You must arise the world around,

Come with the power of Ocean’s waves

And break the chains by which you’re bound.

The Industrial Union Bulletin, and the Industrial Worker were newspapers published by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) from 1907 until 1913. First printed in Joliet, Illinois, IUB incorporated The Voice of Labor, the newspaper of the American Labor Union which had joined the IWW, and another IWW affiliate, International Metal Worker.The Trautmann-DeLeon faction issued its weekly from March 1907. Soon after, De Leon would be expelled and Trautmann would continue IUB until March 1909. It was edited by A. S. Edwards. 1909, production moved to Spokane, Washington and became The Industrial Worker, “the voice of revolutionary industrial unionism.”

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/industrialworker/iw/v4n31-w187-oct-24-1912-IW.pdf