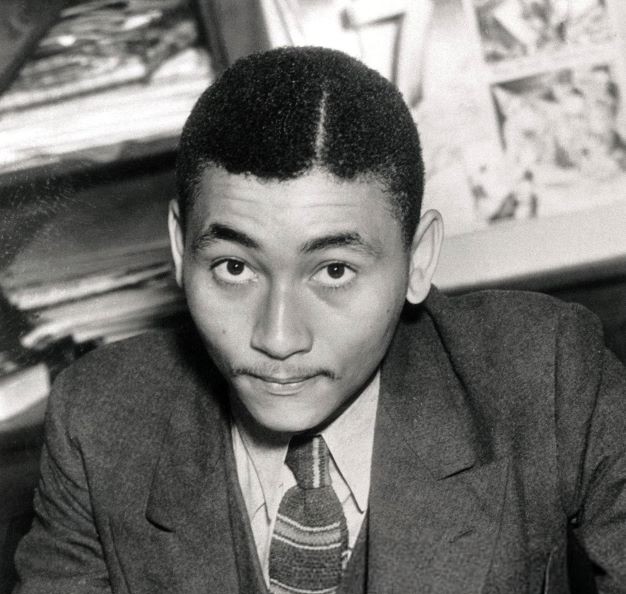

Incredible dignity and bravery in the face of the racist barbarism of capitalist America. Angelo Herndon was a young Black coal miner who joined the Party in 1930 and quickly became a leading organizer. Arrested in July, 1932 by Atlanta police for “inciting insurrection”, he faced the death penalty, but was sentenced to 18-20 years hard labor; the chain-gang. The case would reach the Supreme Court, which finally cleared Herndon in 1937. Here, he tells the story of his activism and arrest.

‘Angelo Herndon–a Leader of the Unemployed’ from Labor Defender. Vol. 10 Nos. 4 & 5. April & May, 1934.

I was born in 1913, in Wyoming, Ohio, a suburb of Cincinnati. My father, who was a coal miner, died of pneumonia when I was very small. My mother struggled with the aid of some relatives, to give me a college education. I was always waiting eagerly for the time to come when I could go out to work, for the family was very large, consisting of eight people.

When I was twelve years old, my brother Leo and I quit school, although mother tried to force us to continue. Our When I was 13, we left home, first stopping place was Lexington, Ky. With the help of some older people, we were able to get work in the coal mines. We started out as coal loaders, getting 42 cents per ton, although the older miners got more. After we had worked for about nine months, our wages were cut from 42 cents a ton to 31 cents. We got disgusted and quit work.

We had some relatives in Birmingham, so that was our next destination.

I went to an employment bureau, and paid $3.00 for a job. After two or three days, I was told that a job had been found for me, out of town. I was to get $3.50 a day as a laborer in helping to construct the Goodyear Tire Company building in Gadsden, Ala. I gladly accepted the offer.

Upon my arrival, I found that wages were only $1.75 per day. A group of us started back. But after a long discussion we decided to stay on. We were to stay in a company tent colony and pay 75 cents per night.

The first day, I operated a concrete mixer. After the day’s work was done, the boss came around and told us that if we would work that night, we would get $3. We agreed to do it. That night my job was setting steel and pouring concrete.

The next day, we were given till 12 o’clock to sleep. Then we returned to work. We continued doing this till Saturday. When the time came for us to get our pay, we noticed a squad of policemen and guards at the pay office. As we formed in line and marched to the pay window, all of us who came from Birmingham were told to get out of line, as we didn’t have anything coming to us. Everything had been taken for transportation, food and sleeping quarters. We were completely stranded. That night we hiked back to Birmingham.

After a few more jobs in mines I began to look for any kind of work I could find. One day a friend and I, in search of work, happened to come across some handbills stuck to a post. We snatched one off.

Later, after looking all over town without finding work, we set our for home. I took the handbill out of my pocket. I saw the startling headline: “Would you rather fight–or starve?” I called my friend. We both sat down and began to read that handbill. Near the bottom, we saw the announcement of a meeting called for 3 o’clock in the heart of the town, by the Unemployed Council. It was almost 3 then, and I said to my friend that we had better hurry to be there when the “fight” started. All the way I said to myself: “It’s war. It’s war. So I might as well get in it now as any other time.”

We got there just a few minutes before the meeting started. A white worker began to speak, saying “Fellow-workers.” He went on to tell us how the Negro workers were being treated, and how the unemployed white and Negro workers must stick together to better their conditions.

I knew very little of what this man was talking about. The next speaker was a Negro worker. He spoke along the same lines as the white worker.

After the meeting, the speakers appealed for membership. I went right up and gave my name.

The next meeting was held in Capitol Park, a Jim-Crow park. About 500 Negro and white workers were present. The same two speakers were there that I had heard at my first meeting. From the park, we marched to the Community Chest, where 100 cops greeted us. When I saw this, I was a little shaky. They stood at the door and let only about twenty Negroes in. I happened to be included in this number. After we were seated, one of the white officers from the Community Chest began to speak. He said that, as far as the Negroes were concerned, the solution to their unemployment was to go back to the farm.

The next speaker was a Negro, robber of the Elks and editor of the Birmingham Reporter. And that was when I began to see the true role of the so-called Negro leaders. He opened his speech by saying: “White brothers and black brothers, don’t be fooled or misled by some foreigner from a thousand miles away, that you don’t know anything about. The Negro has plenty of friends in the South. All he has to do when in need is to go to his Southern white friends. The white labor speaker has tried to get you to accept social equality, but we don’t want social equality, nor do we need it.”

When I left the meeting my blood was hot enough to cook.

In June, 1930, I was elected a delegate to the National Unemployment Convention to be held in Chicago in July. About a day or two before the delegates left, the Kluxers began to raise a cry about social equality. They distributed red hand-bills throughout the city. One was placed at my door. The bills read: “Drive the Communists back to Russia and the North, Alabama is a good place for good Negroes but a bad place for bad Negroes.”

The day after I arrived in Chicago, I was treated to the sight of a demonstration in Union Park. After the city had given the workers the right to use the park, this right was withdrawn at the last minute.

Nevertheless, the demonstration was held. When a worker attempted to speak, police clubs began to fly right and left. Workers resisted the attacks of the police sluggers. A number of workers went to jail and others went to the hospital. About an equal number of sluggers also went to the hospital. When, that night, I read the distorted accounts of the demonstration in the capitalist press, I began to see the truth of what the speakers had been telling me in Birmingham. In fact, the demonstration alone was a better education than I could have gotten otherwise in fifty years.

When I returned to Birmingham, I came an organizer of the miners.

Conditions in the mines were worse than horrible. The company had gunmen patrolling the highways, watching the miners. We had just started talking to the miners when some of the gunmen came up, and we were bound for the jail. This was my first experience in jail.

We were charged with vagrancy. Bail was fixed at $3,000 each. After we had been in jail about seven days, a group of gunmen came to take us to a little company town to be tried.

In a few minutes we were in the courtroom. Within another few minutes, we had been sentenced to twelve months hard labor on the chain gang, and to a fine of $500. But we carried the case to the circuit court and were acquitted.

Before the battle of the share-croppers in Camp Hill, on July 16, 1931, I was sent into the Black Belt to do work. I was in Camden County, home of the present governor of Alabama. It was a very difficult situation for me to work in, but I did what was possible. After being there a few days, I discovered that someone I had had confidence in, a preacher and teacher, had reported me to the authorities in Selma, Ala. A lynch-mob began to form rapidly. It was composed of landlords and country business men. I had to beat it.

I was then sent to New Orleans as representative of the Trade Union Unity League. There was a strike of 7,000 longshoremen. During the course of my work among the strikers, I was arrested and charged with violation of the federal injunction, with inciting to riot, with being a dangerous and suspicious person, with distributing circulars, without a permit, and other charges. I was held for four days, and then released.

On August 3, in Birmingham, three white girls were shot. Two died, one recovered. The shooting happened in an exclusively white neighborhood, but a Negro war veteran, Willie Peterson, was framed for the crime. According to reports in the capitalist newspapers, the Negro had made a “Communist speech” before he shot the girls down.

Next day, while I was out visiting some miners, one of the notorious gunthugs that had arrested me before, came to my room, broke in, and confiscated a batch of literature. Next morning, before day, I was lying in bed, with one of my room-mates, when one of the gun thugs came to the window and put a gun in our faces. Other gunmen broke in the door. My room mate and I were forced to get out of bed, and then handcuffed. When we began to put our clothes on, we were stopped and forced to put on only what they wanted us to wear.

We didn’t know what it was all about. When we got to the police station, we demanded to know what were the charges against us. The thugs told us that we would find out in time.

While we were being questioned, one of the thugs hit me across the head for refusing to say “No, sir” and “Yes, sir”. We were not locked up until 9 o’clock. About one hour later, they came to my cell, and took me about twenty-one miles out of the town. All the while I was being carried to the woods, some of the thugs would point to places where they had killed Negro workers.

After we had gotten far into the woods, the car stopped. One of the thugs asked me if I had my thinking cap on. I said, for what? He answered: “You’ll soon find out.” Then they said: “We don’t care anything about your little old Communist Party, but we want to know who shot Nell Williams and the other two girls.” I said I didn’t know. They said: “If you didn’t do it, you know who did–and you are going to tell us, otherwise you won’t leave here alive.” Two of them pulled their coats off, and slipped a rubber hose from their trousers. I was still handcuffed. Then they started to beat me across the head. One would beat me while the other rested. They beat me for half an hour, but I did not talk. They said: “You god-damn Reds aren’t supposed to tell anything. But before you leave here, you are going to tell plenty.” I said: “I have told you all I know, and that is nothing.”

Then they handcuffed my hands behind me, and started again. They beat me for almost another half-hour. One of them said: “Let me go down in the woods and get mad. Then I will kill the son-of-a-bitch.” I told him he could turn blue if he wanted to.

On the way back to jail, they asked me to point out some of the white comrades. I told them I wouldn’t.

That evening Nell Williams, who had “identified” Willie Peterson by his hat, came to the jail to identify us. As we marched in line before her, she began to shake her head. We could see someone hear her telling her to say “Yes.”

We were finally booked on a vagrancy charge. Three weeks passed before we were tried.

In a few days I was out on bail. The comrades decided that I should go to Atlanta. For 1 week I stayed home, for I was still suffering from the severe blows I had received on my head.

In June, 1932, all relief agencies in Atlanta cut off relief. This affected more than 23,000 people. The county commissioners, with their usual make-believe, handed out statements that nobody was starving in Atlanta.

The Unemployed Council then distributed thousands of leaflets, calling upon the starving unemployed white and Negro workers to demonstrate before the relief offices and demand the continuation of relief. When the workers went to the Commissioners’ offices, no one was to be found. Finally when someone did come to the offices, the Commission locked the door until a group of policemen arrived.

There was no “disorder” or “violence” during the demonstration. The next day, however, in spite of the fact that even the commissioners had admitted that there was no money in the county treasury to provide for relief, they voted $6,000 to aid the jobless. About a week later, when I went to the Post Office to get the mail, I was arrested.

When I demanded to know what I was wanted for, I was told that Solicitor Boykin wanted me. I was taken to the police station, where the police tried to get in touch with Boykin, but Boykin was out of town. Then the police began to question me themselves. One big pot-bellied fellow sitting in a revolving chair and puffing a cigar, said to me: “I used to belong to a labor union myself, and I think it’s a swell idea, but you Reds try to get by the law and you are always hiding. If you meant any good, you wouldn’t always be dodging around.”

Another red-headed, dapper-looking gentleman popped up and said: “You damned guys are nothing but a bunch of degraded bastards. You would drink the blood from your mothers just for the sake of agitating.” Meanwhile, I was playing dumb-brute. One guard asked me where I lived. I told him I didn’t know.

This guard said: “Let’s take this bastard upstairs and give him the works. He thinks he’s in the hands of the New York police. But he can’t fool us.” They led me up a dark flight of stairs into a little dark room. There was a coffin and skulls were strewn around it. In the center was a chair made of steel. One of the men connected some wires to it.

Someone said to me: “Now, if you don’t talk, we are going to electrocute you.” I still refused to say anything. One of the men walked over and slapped me in the face. I told him he would have to kill me before I would get in that chair. Then another said: “Take that bastard back and lock him up.” I was placed in a filthy, lousy place called the “state cell.”

The first six months before I was tried, I was forced to live in a cell with a dead man. I almost died from starvation and lack of medicine. After my lawyers had demanded a trial, time after time, a trial was finally called for January 16, 1933. The trial judge was obviously hostile. He overruled motion after motion that would have given me my freedom. He warned the court to keep quiet, for a man was on “trial” for his life. And he wanted “justice” to be done in this case. The solicitors raved and snorted about Communist revolution and social equality among the white and Negro workers.

Solicitor Hudson demanded that the jury bring in a verdict with an automatic penalty of electrocution. We offered white economists as defense witnesses, to testify as experts on the nature of the literature confiscated from my room without a search-warrant. But the judge overruled this attempt. He stated that the court does not deny the fact that the defendant is an economical (?) man. The defense could make little headway through the mountain of prejudice and the talk of the Red Scare.

The state’s star witness was one of the solicitors who had investigated me before the trial. On the third day, the trial ended with a verdict of “guilty”. The jury recommended “mercy”. Sentence was from 18 to 20 years on the murderous Georgia chain-gang. An application for bail was filed with the trial judge, but promptly denied. A writ of habeas corpus was then filed, demanding bail, and it was likewise denied. A new trial appeal was taken before the State Supreme Court, where it is still pending awaiting a decision.

Meantime, I am still in the death house at Fulton Tower, where I have seen four prisoners go to the electric chair within the past two months. This is further proof that the slave masters are determined to kill me or drive me crazy, from the strain of waiting in the death house.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Not only were these among the most successful campaigns by Communists, they were among the most important of the period and the urgency and activity is duly reflected in its pages. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of original issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1934/v10n04-apr-1934-orig-LD.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1934/v10n05-may-1934-orig-LD.pdf