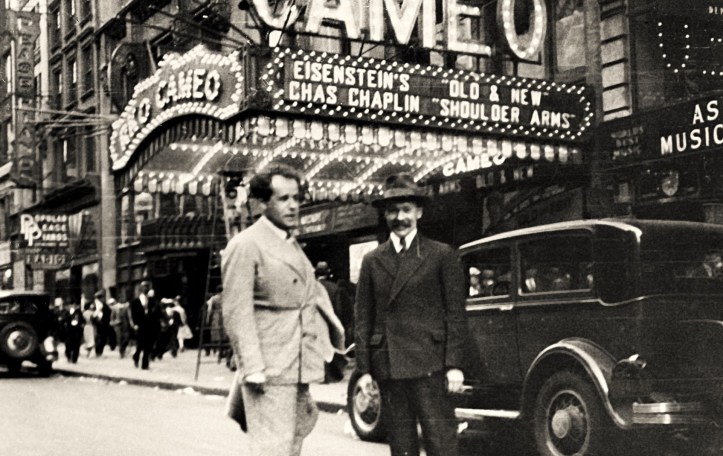

One of the 20th century’s great artists, the pioneering Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein, came to the U.S. in 1930 to try and create art in Hollywood; it did not work. However, it produced several extraordinary observations, as below, on U.S. society and its myth-making, semi-official Hollywood propaganda arm.

‘The Cinema in America: Some Impressions of Hollywood’ by Sergei Eisenstein from International Literature. No. 3. 1933.

I.

When in the days of our tender youth we all studied a little of this and of that and political science according to “Berdnikov” we were thoroughly drilled in the so-called chaos of capitalist production.

But the logic of these dry pages could not displace the image of the Americanized superman, with an adding machine in place of a heart and a time table, accurate to a second, for all life occasions taking the place of an organizing brain. The images of those heroes given by popular novels, of the two legged industrial giants who by pressing a button transfer world markets from one hemisphere to another, those engineers with steel blue eyes enclosing it would seem, the entire atavistic mysticism of the superstitious west-European middle-ages in the steel vise of exact science, mathematical formulas and mechanics, and finally the brilliant, charming, energetic virtuosos of crime in their continuous battle of wits against the no less brilliant and energetic detectives who beat them by “scientific methods” and “exact science” by means of which they uncover their crimes. It is altogether irrelevant that the detective turned out a criminal and the criminal remained one.

The hypnotic charm, beyond good or evil, was always with the inimitably clear, unmetaphysical knowledge of reality, human nature, the complexities of human psychology, three level subways and human relations.

On looking at things domestic or at things passing on the screen one could sense behind them these people that have solved all the secrets of nature, the human personality and can play without error on the keyboard of human passions and interests by means of their exact knowledge.

And suddenly the system cracked.

Cracked on a world wide scale.

Cracked in the very armor of the idealized giant—American technical civilization, exact science and rationalization from water closets to the higher activities of the nervous centers.

Cracked in that visible exterior which, bristling with skyscrapers, so blinded timid onlookers hypnotized by the really overwhelming and tremendous figures of advertized Americanism.

But every hour, every minute, this illusion of a steel giant of exact knowledge is tumbling, collapsing wherever it touches spheres which deviate in any way from the psychological processes by which the crankshaft, flywheel or hoist have their existence.

Just as the Wall Street billionaires sank instantly in the bottomless pit opened by the “great depression,” so sinks into eternal discredit the illusion of a capitalist system, so sinks in the impression of the traveler in the United States, the myth of the steel dragon with an absolute knowledge of the aim, which meant absolute knowledge of the means of achieving that aim.

Only in one direction is the aim, the means of attaining it, and the hysterical application of these means perfectly clear—in the merciless reaction to the revolutionary pressure which hits at the head of the steel giant.

Here there is refined, purposeful, efficient apparatus to crush everything alive and vital, because all that is really vital, that is really alive must irresistibly come and is coming towards revolution.

Hence any moral toleration, permitting, say, the shortening of the skirt by a finger or two, seems to the fanatic American moralist of today a license, a beginning of that which will sweep them from the face of the earth.

II.

Will Hays is called the dictator and czar who holds in his hands the fate of cinematography. The organization headed by him, “The Association of United Film Producers and Theatre Owners of America” is in fact very powerful and can with the speed of an electric current paralyze any undesirable feature that can be forced into the Hays inspection.

On what is this magic power based and what price is being paid for it?

America has no official censorship. The senate at Washington does not refrain from passing a censorship act, suspending it like a sword of Damocles over the heads of the movie industry for the occasion when their product does not morally match up to the standards of the average American housewife or Presbyterian minister.

And the movie magnates create their “Association of United Film Producers” and raise Will Hays to the all-powerful post with almost unlimited powers.

The iron claw of political suppression can be read between the lines of the printed code, giving good advice on moral questions:

Code:

regulating production of talking, synchronized and silent movies. Formulated and adopted by the Association of United Film Producers and Theatre Owners.

The film producers are conscious of the great trust and hopes placed upon them by mankind. They acknowledge their responsibility before the theatre goers entertainment as being factors affecting the life of the nation.

Therefore, although a film is primarily a form of entertainment without definite educational tasks of the character of propaganda—they realize, without exceeding its functions of entertainment spiritual and moral progress, for raising the standards of public life and a more correct way of thinking.

Basic Principles

Not one film is to be issued which may lower the moral level of the onlooker. Therefore—the sympathy of the public must not be invoked in favor of crime, immoral acts evil and sin.

The sanctity of human laws or the laws of nature must not be mocked and infringement of these must not call out any sympathy.

Special Cases Applying

Crimes against the law must never be shown so, as to awaken sympathy for the unlawful act or against the judgement for it or awaken in others a desire to do likewise.

Murder

The act of murder must be shown so as not to awaken a desire to do likewise.

Bestial murders must not be shown in detail.

The influence of alcoholic beverages on the life of Americans can be shown only in such cases when it is necessary to the dramatic structure or for adequate characterization.

Sex

The sanctity of wedlock and the home must be maintained. Lower forms of sex relationships must not be shown on films as commonly accepted or acceptable.

Scenes of passion can be introduced on the film only when necessary or called for by the dramatic structure.

Excessive and lewd kissing, lewd embraces, improper, poses or gestures must not be shown.

In general all scenes of passion must be so treated as not to stimulate the lower instincts.

Seduction and Rape

must never exceed the limits of a hint and only in such cases as it is necessary for the solution of the dramatic knot, but must not be shown with any detail even in such cases. Seduction and rape can never be used as a proper theme for comedy. Sexual perversion or any hint of it is prohibited.

Questions of white slavery are barred.

Race mixture (sex relations between blacks and white people) are prohibited.

Sex hygiene and venereal disease cannot be used as a subject for a film.

Scenes of labor (birth) in natural form or as silhouette cannot be admitted on the screen.

Sex organs of children must never be shown.

Costume

Total nakedness must never be permitted. Under this is understood nakedness shown either in silhouette or de facto, or all seductive and morally corrupting mention of nudity made by any personage on the film.

Scenes of undressing must be avoided and permitted only in extreme instances.

Dance costumes made with a view to improper exposure or improper movements during dances are prohibited.

Dancing

Dances hinting at sexual relations or showing such or improper passion are prohibited.

Religion

No film or episode can show any religion in a ridiculous light.

Ministers of the cloth or other servants of the cult must not be shown as comic persons or villains.

Places of Action

The treatment of bedroom scenes must show delicacy and conform to the dictates of propriety. The subjects enumerated below must be treated carefully and in good taste:

Execution by hanging or on the electric chair, as lawful punishment for crime coMmitted.

Third degree methods of examination.

Rudeness and excessive pessimism.

Brandmaking of persons or animals.

The sale of women, or a woman selling her virtue.

Surgical operations.

Follows the text of the singular oath of duty, handing over the fate of movies to a preliminary censorship, a censorship during production and a final censorship upon completion at the solicitous hands of Will Hays’ organization. The instruction ends up with the following admonition:

“In consideration of the aforesaid, it is resolved that the following methods shall be adopted in practice:

“On demand of the officers, The Association of United Film Producers must gather facts, information and propositions relative to the acceptance of scenarios or their manner of treatment.

“Every movie producer must submit to the Association all films produced, without any exception, before the negatives are turned into the laboratory for printing.

“The Association of movie producers, after viewing the film, informs the production manager in writing of its opinion on the merits of the film with regard to the code above, underlining and pointing out those subjects, treatment, or episodes, in which the film infringes the code.

“In all cases of infringement of the code, the film can not be issued until all the corrections indicated by the Association have been made.”

In such instances of disagreement with the Hays censorship, as one movie magnate expressed it, “We take and retake the scene until it resembles a woman who having lost her innocence also loses the rebelliousness that agitates the censors.”

Assuming the post of producer, manager, supervisor or chairman of the board, one must take an oath to invariably follow the above code.

And if you will overstep it—you will be forced.

But vulgarity—means money, and sensationalism—means money. And money—means everything.

So we see on the screen a most head breaking game of cat and mouse that the Hays organization plays with itself. More correctly, the moral bosses of this respectable institution are beaten by the interests of the actual commercial bosses whenever the movie industry gets an opportunity to make a hit on a morally doubtful or even altogether Scandalous piece of sensationalism.

Not in vain is the phrase repeated, with the roll of a small drum:

“If it is absolutely necessary and called for by the dramatic development of the action.”

Under the powerful pressure of scandalous sensationalism, twenty-five dead bodies are dragged through this loophole in the film Beast Over the City showing a battle between police and Chicago beer king bandits. In Shame of a Nation just as many dead bodies strew the path of the film winding up with a formal siege of his iron clad lair where he heroically succumbs to a suffocating gas bomb on the edge of an incestuous affair with his own sister whose lover he has shot out of jealousy.

The inflated by advertizing doubtful “charges” of this film entirely evaporate into a hymn to the powerful personality of the “strong man” to which the hearts of little clerks and stenographers respond, and the mutual destruction of beer kings is very much like the relentless battle of their financial bosses on the exchange or their social benefactors in preelection and election fights.

Some “beneficial” educational value, of course, can be gleaned even from this: a parade of the police fully armed to crush those attempting to break the law may warn those “other” lawbreakers who rebelliously prepare red flags for May 1st. A tear gas bomb does not care at whom it is thrown!

III.

King Vidor did an unheard of thing—a Negro film. His last argument was a sacrifice of salary. King Vidor agreed to share the risk with the firm. King works not on a safe salary basis, but on an uncertain percentage of the profits basis.

Irony is inseparable from pathos.

A true follower of the not unknown skirted messiah, Mary Baker Eddy, King Vidor is enchanted by the jazz ecstasy of African Methodists.

But the methods of administering the religious poison, the economic exploitation of religious feelings, are so wildly grotesque in themselves that in spite of the well intentioned religious enthusiasm of the producer, the full grotesqueness and buffoonery of the new messiah racket comes out.

A Negro preacher, provided only by the able enterprise of his black parents with an aureole of sanctity, a special Pullman coupled to a freight car in which there is a special ass, like a Christ enters “on an ass” the city of many sins, that pours out to meet the new Colored prophet.

But in the crowd there is a Colored prostitute with her pimp who were witnesses at that drunken orgy at which the present preacher, then a cotton trader selling the product of his father’s farm, having spent the money realized on drink in a drunken rage shoots his brother, and is illuminated by a heavenly light and hears the call to “go forth unto man and sear their hearts with words of fire.”

The prophet’s partners in the recent orgy, the initiators of the spree, ridicule him in spite of the holy mood of his public.

Undisturbed in his serenity, the prophet calmly dismounts his ass surrounded by an angelic chorus of black children in white muslin, and expertly beats up the insolently laughing mug of the pimp.

After which he calmly continued his entry of the new Jerusalem, having turned his boxing fists into heaven directed palms.

But God’s ways are unfathomable. In one of the succeeding reels the sinful maiden is brought to the sacrament of second baptism in the waters of one of the branches of the Mississippi.

Ecstasy enters the God directed soul of the sinful maiden dipped in the cold waters of second baptism.

The ecstasy is transmitted to the newly arisen baptizer.

The girl feels sick. The girl loses consciousness. The baptizer picks her up in strong arms and carries her to a tent on the shores of the flowing river. Only the interference of the provident mother of the prophet saves the religious ecstasy from turning into something even shameful for she grabs him with an energetic black arm and tears him away from the camp bed on which the converted sinner lies, whom the Lord God may enter but not his undeserving servant.

The ceremony of saving souls by dipping bodies in cold water is in full swing and the undeserving servant must return to his workaday drudgery.

The girl later becomes such a frenzied addict of virtue that when her pimp comes to her to turn her back to sinful ways, she lams him with a poker and repeats in a shrill voice:

“That’s what I’ll do to everyone that steps between me and my salvation.”

There are many ways of taking a risky dreamer down a peg. If it is hard to convince the creator of the Big Parade of the economic imbecility and racial impropriety of taking up the theme of the blacks, there’s the flexible network of the renting apparatus which can, by able tactics, paralyze the successful run of its own products even though made in foolhardiness by such big fellows as the director of Big Parade, not to speak of smaller fry.

King Vidor himself told me how Hallelujah was knifed by their own renting agents.

The paragraph of the code covering racial problems reigns supreme.

The losses of Hallelujah are covered by the profits of the Big Parade.

But what are losses compared to the lesson taught that Negro films don’t pay, that incontrovertible argument remains in the arsenal of race hatred, subtle tactics in that same class struggle to discourage all those who may ever have a desire to touch again the black taboo.

A Color film, not at all in “natural colors,” but on the fate of Colored people in America was one of the first subjects we proposed to Paramount. And our first creative initiative was paralyzed by the cold horror of the company at Negro films which don’t pay: “there’s the sad experience of King Vidor’s picture.”

The ironic smile at the religious conceptions’ of a lower race, not without cunning passed by the code, avenges itself, and Hallelujah shoots higher than the aim—over a particular incident, into the religion of the system, into the thirty-three religious systems of America.

IV.

So much has been said, written, and told of how the “bosses” of the movie industry come out of the cosmic chaos of speculation in real estate parcels and old clothes, the victorious circles of manufacturers of chewing gum, natural and artificial fertilizers, that I am reluctant to again broach this subject. It will be better to touch on the living people of the curious last conflict within the leading circles of the movie industry that in 1930 completed the thirtieth year of the first stage of American cinematography. I was a living witness of all that which has been swept off the face of the earth without leaving a trace by that “mighty hurricane” the Wall Street crash and the general crisis and economic depression.

Fox, Lasky, and other veterans of the American movie have been thrown out of the game by the depression. I caught them yet, saw these lions of the movie industry, heroes of the highway, first pioneers that came to discover Movie-California on wheel and horseback, just as in forty-eight flocks of gold seekers rushed to the California gold fields. Not the celluloid gold fields of Hollywood but the gold dust of the river Sacramento, of the fat soil on the estate of the general John Sutter, the hero of another rejected film subject of ours, around the California gold rush in the forties.

The bosses were really scared at the idea of letting “Bolsheviks” handle the subject of gold.

The old movie industrialist was a movie adventurer, a desperate player in the dark—the darker, the surer–excelled in sweep, imagination, and was irresistibly drawn to the risk of the game.

America even now plays on everything possible. Half of the speculation of an election campaign is made up of a great number of bets on this or that candidate, as on the leather glove of this or that boxer, the legs of a race horse or of a greyhound.

On a bet, as in the days of the great Mark Twain, tremendous frogs are raced every year in the region of San Francisco.

At the tables of an ocean steamer logbook eagerly crowd holders of sweep stakes on who will guess closest the number of knots the ocean skyscraper will make that day.

Our own five week stay on the border between Mexico and the United States was the cause of not a few dollars changing hands in Hollywood on bets whether we will be readmitted to the land of Major Pease or not.

This old type of movie business man, adventurer, dreamer, sportsman, poet of profit, is being replaced by prosaic adventurers not of the boundless prairies and pampas, but of the dry clatter of adding machines, bank operations, adventures on the exchange.

I was present at the last rounds of the death between the old romantic pioneers of the movie industry and the dry bureaucrats—creatures of Wall Street without initiative, avoiding anything that is not absolutely certain beforehand of bringing in sure returns.

At their hands only a sleepy shroud of endless repetition comes and creative initiative is crushed, although against all logic it once in a while escapes on the shores of golden California.

These are cutthroats without a gleam of romance about them. But they were the victors in the battle.

It is surprising that the accuracy of bank accounting, the exactness of exchange deals did not take root in the chaotic factory kitchen of Hollywood.

Nowhere will one find a greater thirst for the unknown blessings of the god success, a more panicky trepidation before him; and a more complete ignorance of how to win him, how to serve him, how to please.

Chaos, chaos, and chaos.

Chaos in everything that in the least departs from the process started by turning the lever of an automatic machine or the endless conveyor of technical processes. In everything that is not electro-mechanical, physical or chemical, purely technical.

Or in anything creative that cannot by constant repetition be brought to the ground, triteness, the low level of dull automatism, standard lighting, standard cast, a standard Tom Mix on a standard mare.

A total disorientation in what is needed and how, what is good and what is bad, even in what is profitable and what isn’t—which is after all the end of this game of blind man’s buff with themselves.

The voice of the prudent cries only for the endless repetition of what once was successful. The voice of the madman calls only for sensations, of whatever order you please from a dance of fresh feet or bellies on the pavement of Broadway to the next crowned Bourbon who just lost his inherited throne again.

Do you think Trotsky could write a scenario? was the first question on my first acquaintance with Laemmele, the Hollywood “Uncle Charles,” head of Universal, one of the first pioneers into the unknown, then infant movie industry.

When I shrugged my shoulders at the hand cupped at his ear he continued:

Would he come to be photographed?

And after a while the old man did send a telegraphic proposal to come and be filmed—to the Spanish Alphonse.

For quality Hollywood makes up in quantity.

The uncle of a friend of mine used to say, “Don’t pass up a single girl and you may sometime come upon a good one.”

On this principle Hollywood works with respect to scenarios, stars, authors, producers, musicians, artists.

Everything is bought. Snatched from under one another’s noses. Throwing out tens, hundreds of thousands of dollars, they are all collected under the brilliant California sun that shines the year round.

They all drink hard, run around in wonderful automobiles breaking all traffic rules and speed limits when the policeman doesn’t look, buy him off when he does, when he catches them on his motorcycle; they get tanned, smearing themselves with thick layers of cream against sunburn, go in for ocean bathing, but mainly for their weekly checks, for which in a fit of conscience they think up schemes for creating eternal values.

Then it appears that 90 per cent of these people famous somewhere for sham or real qualities are useless to the movies and sumptuous greetings at pseudo Spanish style cottages of movie magnates and stars are replaced by silent departures with current accounts fatter than before.

In the loss columns of the company appear another ten thousand dollars or so. And the serviceable triangle of the inured scraper removes some more black letters from the glass of one of the thirty to forty scenario offices or one of the twenty or so producer’s offices.

In a week the dark letters of another famous name appear on the door, and behind it another eminent light will sit bored and yawn, catch flies while waiting for his appointment with another imported wonder on the golf links.

Should this new eminent guest, by rare accident, get some shadow of an idea into his head, he will have to try for about ten days or so to obtain an interview with the manager, who will give him three minutes to tell, amid the noise of telephones, dictaphones and hoarse shouts of loud speakers, of what, to everyone’s really great sorrow, had the temerity to enter his head.

The presence of these great lights is dictated primarily by advertizing considerations, and the daily routine payroll brokers. Should after a stay of many weeks, a rachitic offspring of the departed dramatic genius remain to squeal, this semi-practical original will fall into the hands of expert nurses who will not fail to make of it the hundred and first variation of the same eternal triangle story.

In general the guest is faced by two dilemmas: to forget personality and convictions, climb the golden merry go round and merrily turn out merry products without taking things too seriously—like Lubitsch; or take a tragic view of things and leave the promised land like Reinhardt.

But how I shall be asked, does Hollywood, with this chaos, confusion and lack of system succeed in flooding all its own and the world’s markets with a sufficient, if not to say excessive quantity of movies?

On railroads, willy nilly, a certain number of accidents will occur year in year out.

Out of a hundred scenarios one must turn up more or less possibly good at least for doing over.

Do you need a hundred scenarios?

Assume ten per cent good ones.

And Hollywood buys ten thousands.

Where a business is conducted not om scientific principles and the logical results of analysis, of long years of experience, the business will necessarily be drawn into the debauchery of unaccounted volume, large staffs, and useless expenditures counting largely on statistical probabilities: to a hundred items of trash one, two, perhaps three worth while.

The debauched, unbusiness like chaos is due principally to the disproportion between expenditure and income in the movie industry.

The mistakes and groping in the dark of a group of unwise is more than made up by the foolishness of millions of users, in their unending thirst for spectacles ready to swallow any trash.

In addition the theatregoer is safely bound in the chains of the chain system of theatres, giving him no choice but to take what is offered.

Where there is no clear cut analytically scientific understanding in the organization and technology of the creative processes, there can be no systematic education of youth, no rational education in cinematography except the Shamanistic adventurism of private speculative “movie studios,” that generally prepare youth for totally different purposes.

The necessity for conscious efforts at self preservation in the merciless struggle of competition dictate the putting up of a triple ring of barbed wire around the sacrosanct territory of moviedom.

Youth not only is not educated.

It is barred out by triple bars on impenetrable gates.

The circular of the past president of the Academy, William DeMille, that has appeared in all newspapers in the United States says:

“It is necessary to adopt measures to convince youth that it is unnecessary in Hollywood. The situation is a strained one as there is an excess of unemployed in all branches of movie production.

“Out of seven thousand actors and actresses registered at the call bureau only six” or seven people were employed a day. If the number of calls were divided by the number registered it would show that one can expect to get a role once in three years,

When the industry is in such a position that it cannot employ its experienced actors, any attempt of young people to push through is tantamount to suicide…”

Out of 17,500 extras registered in 1930 at the central actor’s employment bureau only 883 had on an average one day’s employment a week and only 95 worked three days a week.

Talented youth can really only end up in suicide or crawl about in fruitless search of “a pull” with one of the numerous relatives of movie magnates that grace their companies.

That was in 1931.

Now when stars that once shone alone in bright miles of film are compelled to cluster in groups of five or six in one picture with a corresponding distribution of the laurels the plain mortal that once played leading roles are forced by economic pressure into the rows of paltry “extras” to earn a grub stake from role to role.

V.

And this squalor of ideas, thought and thriftlessness is served by the world’s most perfect technical apparatus. And here to balance the sombre colors of the picture painted thus far, one must sing a hymn of praise not only to the technical achievements, but to the unending reserves of labor, energy, time, and money which are spent to solve the smallest practical and technical problem in detail.

Skyscraper research laboratories om acoustics and the perfection of the microphone, reequipment of entire million dollar buildings and outfits in the sound registering system, chemical treatment persistent effort to increase the sensitiveness to light of emulsion—all this converts the seemingly dreary field of production technology into a continuous live stream of improvement and technical triumph.

Rational differentiation of the executive apparatus, high qualification of the units composing it, headturning speed of taking and serving news reels and the existence of special news reel theatres; the ability even though wrongly in their own way, perhaps in pursuit of sensation, but with plenty of flexibility and speed to react to facts and events of the stirring present; the brilliantly functioning network of rented theatres, even though on a commercial and not cultural footing, but embracing all of America inclusive of the smallest hamlets; finally the great sweep of the movie industry as a whole, giving it the respectable place of third in size of the largest industries of the United States assuring to it in this way a sufficient material basis for continuous technical development—all this cannot but set us fiercely to thinking on these points, on all of which we sin doubly living in a system of all embracing planned economy of socialist sweep, which, on rational approach, gives us incomparably greater possibilities on all lines than decaying capitalism.

And we must always have before us with unbending and unceasing persistence and flaming enthusiasm the slogan “Catch up and Surpass” on those positive features which can be found in the achievements of the class enemy.

An uncompromising realization of this slogan, instilling our ideology and our content into a fully developed technique which “in the period of reconstruction determines everything”—this is the bolshevist task which stands before our cinematography as a whole at the moment of our victorious entry into the second five year plan.

Translated from the Russian by S.D. Kogan

Literature of the World Revolution/International Literature was the journal of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers, founded in 1927, that began publishing in the aftermath of 1931’s international conference of revolutionary writers held in Kharkov, Ukraine. Produced in Moscow in Russian, German, English, and French, the name changed to International Literature in 1932. In 1935 and the Popular Front, the Writers for the Defense of Culture became the sponsoring organization. It published until 1945 and hosted the most important Communist writers and critics of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/subject/art//literature/international-literature/1933-n03-IL.pdf