While different left groups were involved to a greater or lesser degree in all of the large strikes of that turning-point year of 1934, it was only in the San Francisco General Strike that the Communist Party exercised a central leadership role. Here, an official summation made immediately after on the role of the Party in those momentous events.

‘The San Francisco General Strike and Its Lessons’ by B. Sherman from Communist International. Vol. 11 No. 17. September 5, 1934.

The general strike in San Francisco and surrounding cities, and the Pacific Coast maritime workers’ struggle which led up to it, took place in the midst of the second big wave of strike struggles sweeping the United States and continually rising in the level of militancy and displaying an ever more clearly defined political character.

The longshoremen’s strike on the Pacific Coast broke out on May 9 around the demands for higher wages, the 30-hour week, union control of the hiring halls, and a united West Coast agreement with a uniform expiration date. The strike from the first was under the leadership of the militant rank and file in the A.F. of L. longshoremen’s union, the Industrial Longshoremen’s Association, and was called in spite of every effort of the district and national officials to prevent it. The strike rapidly spread to the seamen under the leadership of the Marine Workers Industrial Union, which forced the A.F. of L. seamen’s union to call their members on strike as well. In a short time, ten maritime unions were involved, with a total of 35,000 strikers, and all shipping activity on the Pacific Coast was completely tied up. In San Francisco, the strongest and most militant center of the strike, a united strike committee of 50 was set up, with five representatives each from the ten different unions.

From the first the strike met with the most violent attacks by the police, armed strike-breakers, and the National Guard against the mass picket lines, and in a number of pitched battles four strike pickets were killed and over 300 injured. At the same time the capitalist press launched a violent attack on the militant strike leadership, and tried to whip up an anti-Communist hysteria without success. The sympathy of the workers for the strikers expressed itself in the rapidly spreading sentiment for a general strike. Forty thousand workers attended the funeral of the two pickets killed, one of whom was a member of the Communist Party.

Movements for local general strikes had already taken place recently in many centers throughout the country, in support of the Toledo auto workers, Minneapolis truck drivers, Butte miners, Milwaukee carmen, and on the Pacific Coast. The workers in Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, and San Pedro were demanding a general strike in sympathy with the striking maritime workers and against the police and military terror of the government. Only in San Francisco, however, did the general strike materialize because precisely in San Francisco the leadership of the maritime strike was firmly in the hands of the militant rank and file strongly influenced by the Party, and the whole strike assumed the character of a united front struggle against the employers and the government.

The reason for our strength in San Francisco, as distinguished from other strike situations where the Party stood on the outside of the struggle, is that already in the middle of 1933, when the majority of the longshoremen showed their desire to belong to the A.F. of L., the Communists actively participated in the organization of the longshoremen into the A.F. of L. local union. The A.F. of L. district and national officials of the I.L.A. worked day and night to prevent the strike from taking place and, after it broke out, to send the men back to work, but their every effort and their every maneuver was defeated by the local strike leadership which represented the sentiments of the rank and file.

The firm stand of the strike leadership in San Francisco also helped to influence and strengthen the Position of the strike in the other Pacific Coast centers, where to a large extent the rank and file was also able to gain control. The National Longshoremen’s Arbitration Board appointed by Roosevelt made strenuous efforts to break the strike and submit the strikers’ demands to arbitration, but neither they nor the A.F. of L. leaders succeeded in this. When the A.F. of L. leaders signed an arbitration agreement, the strikers rejected it and Ryan, the I.L.A. national president, received such a hostile reception at the strikers’ meeting that he was unable to speak,

The policy of the Party was to spread the strike, not only to all branches of the marine industry on the Pacific Coast, but to the Atlantic and Southern ports. However, our extremely weak position in the A.F. of L. unions in those other ports made it impossible to spread the strike into a national strike of longshoremen and seamen. Only in a few instances was the Marine Workers Industrial Union able to call strikes of seamen on a few ships.

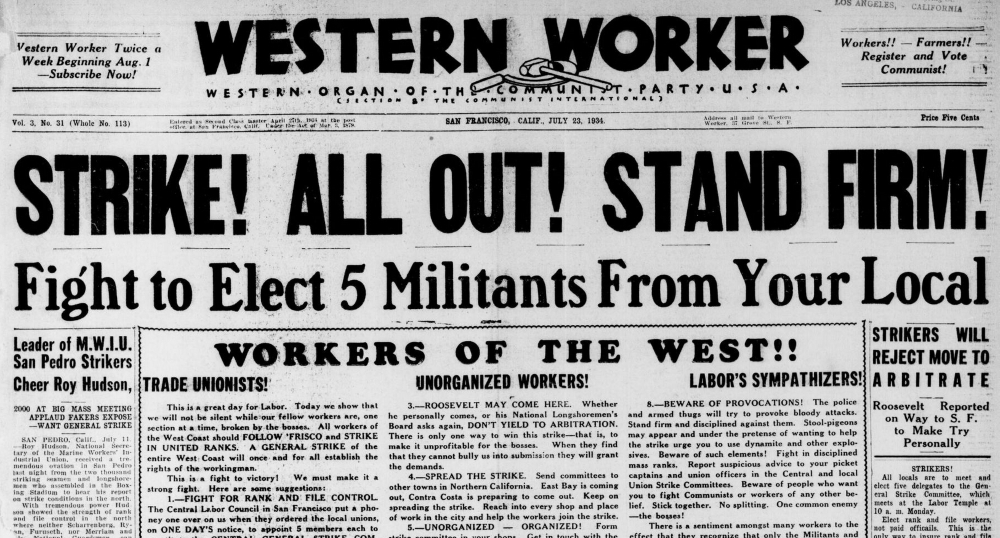

In the face of the unyielding position of the employers, the question of developing a movement for a general strike in Pacific Coast ports in support of the maritime strikers, became an extremely urgent one. The influence of the Party among the strikers was so great that the San Francisco strike committee decided to make the “Western Worker”, (the Communist Party weekly organ on the Pacific Coast) their official strike organ. The strike committee, after enlisting the support of the A.F. of L. and revolutionary unions in the marine industry, further extended its activities for the development of the general strike in San Francisco, the sentiment for which spread rapidly.

Local union after local union voted in favor of the general strike. A mass meeting of 18,000 workers called by the Maritime Strike Committee cheered the slogan of “general strike”. The A.F. of L. leaders of the San Francisco Central Labor Council moved heaven and earth to head off the movement, and even wired President Roosevelt to intervene to prevent a general strike. President William Green telegraphed to the Seattle Central Labor Council warning them that a general strike would violate the laws of the American Federation of Labor, and would be unauthorized.

In San Francisco, the local labor leaders set up a “Strategy Committee”, to hold off action and dissipate the movement. However, when the Maritime Strike Committee called a conference of the A.F. of L. unions to discuss a general strike, at which 26 local unions were represented, the local labor misleaders, fearing that the movement would go over their heads and slip out of their hands, changed their tactics and decided to head the movement in order to be better able to behead it. They called a special conference attended by 115 local unions, where only three local unions voted against the general strike, and a general strike committee was set up, to which each local was to appoint or elect five representatives.

The Party mobilized for the election of representatives, while the A.F. of L. strove to get only officials appointed. The real power, however, was in the hands of an executive committee of 25, consisting of officials appointed by the labor bureaucrats, and including only one militant representative, the leader of the striking longshoremen. It should be noted that at the time the A.F. of L. leaders called the special conference, the momentum of the general strike movement had reached such a character that the economic life of San Francisco was already partially paralyzed by strikes of teamsters, street-car men, butchers, etc., and other trades were preparing to walk out in the following day or two.

The General Strike began on July 16 in San Francisco, spreading on the following day to other nearby cities, Oakland, Berkeley, and Alameda, until it involved about 125,000 workers in a metropolitan area whose population was 1,200,000. Everything was at a complete standstill, and the only operations permitted were a few restaurants, truck deliveries to hospitals, etc., under strike committee permits. Every day, however, the misleaders heading the executive committee relaxed the tie-up by issuing more and more permits for business activity, preparing for the final sell-out.

Meanwhile, the press opened a hysterical campaign against the Communists, and shrieked about “revolution” and “insurrection”. The employers radioed an appeal to Roosevelt, on board a warship bound for Honolulu, to cancel his trip and come to San Francisco to settle the strike. Senator Wagner flew by plane to Portland, and succeeded at the last minute in averting the general strike which threatened there. General Hugh Johnson, head of the N.R.A., came to San Francisco and gave the keynote for the terror wave which followed, when in a provocative speech he called upon the A.F. of L. leaders to wipe the Communist influence out of the unions, and openly encouraged fascist gangs to take matters into their own hands. The Mayor and Governor made radio speeches that this was not a strike but a “Communist revolution”, and 7,000 troops of the National Guard were moved into the San Francisco area. Secretary of Labor Perkins telegraphed that the government would cooperate by deporting all alien Communists. With the stage thus set, on the second and third day of the strike, raids began along the entire Pacific coast by fascist gangs of “vigilantes”, followed by police, against the headquarters of the Communist Party, the Western Worker, the maritime unions, and homes of workers, where everything was wrecked, workers beaten up and arrested. The printing plant which printed the Western Worker was destroyed by fire. About 500 arrests were made, some comrades were charged with criminal syndicalism carrying heavy penalties, and fourteen workers were held for deportation.

It was not until this reign of terror was well under way, that the labor misleaders in their turn took the offensive. On the third day of the strike, the General Strike Committee voted 207 to 180 to call upon the maritime workers to submit their demands to arbitration, and on the following day the General Strike Committee voted 191 to 176 to call off the general strike. In spite of the terror wave, the close vote in a committee packed with A.F. of L. officials shows how the sentiments of the workers really stood. The street-car men continued their strike for several days. Nevertheless, the intimidation and the sell-out had some effect and a week later the maritime workers, who had continued on strike, voted to submit their demands to arbitration, on condition that the unions of the seamen should be included in the settlement, and refused to go back to work until this was agreed to. This solidarity of the longshoremen with the seamen, and their repeated refusal to settle the strike unless all the strikers were included, was an outstanding feature of the strike, and especially significant because in the 1919 and 1921 strikes, due to the policy of the AF. of L. leaders, the longshoremen and seamen did not support each other. The strike therefore ended, after more than three months of struggle, as an organized retreat, and the unions have forced the employers to negotiate with them on all disputed questions, which is in itself a significant concession in spite of the fact that the betrayal by the labor officials prevented the strike from ending in victory.

What are the lessons and conclusions that can be drawn from the maritime strike and the San Francisco general strike?

1. The working class, after a year and a half of the New Deal, has been aroused to an unprecedented fighting spirit, whereby the smallest action for economic demands calls forth solidarity strikes and protest actions in which the unorganized workers and the unemployed fully participate, developing into general strike actions of a political character. This is evidence of the profound ferment and radicalization rapidly developing among the masses as the illusions in the Roosevelt program are evaporating. It is of the utmost importance that the Party utilize the experiences of the general strike, drawing the necessary conclusions, and widely popularize its lessons among the broadest masses, paying special attention to consolidating and extending its influence among the workers and in the local trade union organizations in San Francisco and other centers of strike struggles. While the Party has correctly answered the cry of the capitalist press about “revolution”, by pointing out that the general strike was not a revolution but a struggle in support of the immediate economic demands of the workers, it is also necessary for the Party to draw the necessary political conclusions, and point out the significance of the general strike in the present period in its relation to furthering the revolutionary struggles of the proletariat. The longshoremen’s strike, as well as the general strike in San Francisco, has shown that through united front mass struggles, the workers can defeat the employers’ moves for company unionism.

2. The main stream of the strike movement for economic demands and against company unions continues to develop in the main through the reformist unions, despite the feverish efforts of the A.F. of L. leaders to prevent the strikes, and if the leaders do not succeed in this, they strive by all possible means to retain leadership of the struggle in their hands, and increasingly use the S.P. and renegades (Trotskyites) to behead the strike movement.

3. With the exception of San Francisco, to a lesser extent other Pacific Coast ports, and also Milwaukee where the Party has shown good leadership, we have remained outside of many important strike struggles in the present big strike wave and did not directly influence the leadership of these strikes. One of the main reasons for the weak position of the Party in the present strike wave is that we did not see that the tremendous surge for organization and struggle took place, in the main, through the American Federation of Labor. The already-mentioned features of the present strike struggles offer the most favorable opportunities for the Party in placing itself at the head of the strike movement, provided we place the main emphasis on the militant leadership of, and participation in, strike struggles through our activities inside the A.F. of L. unions and among the strikers following reformist leadership. The lessons of San Francisco are that by placing the main emphasis on work within the A.F. of L. and at the same time skillfully organizing the militant actions of the Red union, even though the union is in a weak position, and developing the united front with the A.F. of L. workers and the independent unions, etc., we can achieve important results in organizing and leading strike struggles. of the workers, despite the resistance of the A.F. of L. leadership.

4. It is urgent that in the preparations for the coming A.F. of L. convention to be held in October in San Francisco, the scene of the general strike, an opposition program be worked out dealing with the pressing issues raised by the strike movement, and it is essential that we work to have a substantial opposition delegation to the convention and to win positions in the local unions and the Central Labor Councils. At the same time, the Party must foresee and be prepared for any new “Left” maneuvers of the A.F. of L. leadership at the coming convention, in the direction of giving a pretense of more democracy, recognition of the industrial union structure of the Federal locals, etc. The experiences of the joint activities of the ten unions connected with the port of San Francisco show the value and need for continued collaboration and coordination of the activities of these unions following the strike, in order to preserve the gains of the strike and for further struggle. In view of the experiences of the joint strike committee of ten, the Party should advocate the advisability of unification of the existing crafts into one union.

5. The Party, although functioning well under conditions of the terror, issuing the Western Worker and leaflets to the troops illegally, and the leadership functioning intact in spite of the raids, under-estimated the extent of the terror and was not prepared for it. Although issuing the slogan of organizing mass self-defense corps, nowhere was any such mass self-defense organized effectively, and working class organizations were not organized for the defense of their headquarters. Even the wrecking of the union strike headquarters was carried through without resistance, although the employers openly spoke of the attacks in advance. In the centers of the terror wave especially, a broad united front movement for mass self-defense must be organized.

6. A nationwide protest movement against the terror must be carried on, drawing in especially A.F. of L. unions and Socialist Party locals, in defense of workers’ organizations. At the same time, it is necessary to utilize the Lundeen resolution introduced into Congress last May, demanding an investigation of the terror, which the Party has not utilized at all.

7. The gains made by the Party during the strike must now be consolidated and further strengthened. It is necessary, first of all: (a), to build the opposition and increase our influence in the I.L.A., and to organize opposition groups in every local of the A.F. of L., also with the aim of building up an opposition within the Central Trades and Labor Council; (b), to build up the Marine Workers Industrial Union amongst the seamen, and to establish close united front connections with the reformist seamen’s union and the building up of opposition groups there. On the basis of joint activities of the M.W.I.U., I.L.A., and reformist seamen’s union, to advocate the formation of a local federated body of these unions; (c) to increase and consolidate the political influence gained by the Party during the strike, it is necessary to increase the circulation of the Western Worker and establish it as a mass paper on the West Coast; (d), to take the utmost advantage of the present favorable opportunities to build the Party in California into a mass Party by bold recruitment. It is most urgent to overcome the fluctuation of the Party there, which is expressed in the present alarming situation of a decline of membership in face of the large recruitment.

Finally, a campaign must be organized against the arbitration legislation, for the repeal of the Labor Disputes Act, and in support of the workers’ demands now in the hands of the arbitration boards, backed up by the sending of workers’ delegations and resolutions demanding the acceptance of the workers’ demands.

The San Francisco general strike, and the movements for local general strikes in other centers throughout the country, bear eloquent testimony to the correctness of the estimation given by the Thirteenth Plenum of the E.C.C.I., and particularly of the point indicating the inevitability of economic strikes more and more interweaving with the mass political strike. The historic significance of the San Francisco general strike will leave its imprint on the future development of still greater class battles during the approaching second round of revolutions and wars. The Party must see to it that these lessons are made the property of the whole working class.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-11-brit/v11-n17-BRIT-sep-05-1934-CI-riaz-orig.pdf