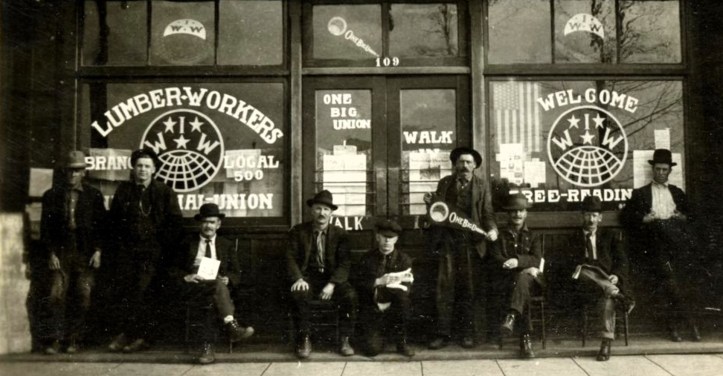

Payne, a wobbly organizer in the logging camps of the Pacific Northwest on how the I.W.W. developed an organizational method based on agricultural workers. As the U.S. entered WWI rolling strikes hit the industry, with the main demand for an eight-hour-day. Shortly after this article, on June 20, 1917, Lumber Workers Industrial Union No. 500 called out all Northwest timber workers out, with tens of thousands answering the call becoming one of the major war-time strikes.

‘The Spring Drive of the Lumber Jacks’ by C.E. Payne from International Socialist Review. Vol. 17 No. 12. June, 1917.

A NEW method of organization is being tried out in North America, an invention which, like many another, is so simple and yet so efficient that the wonder is not that it has been discovered, but that it has not been tried before. This new machine is the Lumber Workers Organization No. 500 of the I.W.W.

Formerly when the timber workers in one locality became numerous enough to form a Local Union they took out a charter for that locality, and the certain result was that when the members would leave or be driven out, the Charter would lapse, and people would say that “the lumber jacks won’t stick together.”

The lumber workers who are now organizing in the L.W.O. were at first accepted under the jurisdiction of the Agricultural Workers Organization, but they became so numerous and their activities were in some respects so different from that of the A.W.O. that a convention was called to meet in Spokane on March 4th. It continued for three days, and resulted in an application to the I.W.W. The charter was issued on March 12th of this year, and the members engaged in the lumbering industry who had been members of the A.W.O. began transferring to the L.W.O. No. 500, and new members have been joining at a very encouraging rate. The number in good standing at present is close to 6,000.

The new form of organization is that of an Industrial Union with branches, and it has jurisdiction in the lumbering industry throughout the entire country. The headquarters is located at 424 Lindelle Block, Spokane, and the Secretary, Don Sheridan, and three assistants have all the work they can handle, and more coming in all the time.

There are district branches at Spokane, Duluth and Seattle. Duluth district has three branches, Seattle has seven branches, and Spokane has some seven branches, while each district and branch has a number of stationary and camp delegates working with credentials. Organization is being carried forward in Louisiana to establish a Southern District, and work is being started in California. Wherever there are a number of districts near each other they function as a district. On the other hand, where logging and milling operations are discontinued in some section of country, there is no lapsed charter because of the members moving away, but some Stationary Delegate who has a suitcase full of literature, stamps and cards simply moves to the new location, and the business of organization goes on.

The new arrangement means that there is but one Lumber Workers’ Charter for all North America, and every member belongs to the Industrial Union, which has headquarters at Spokane. But this does not mean any hard and fast rule of action. Each district is left free to tackle the boss whenever they feel so inclined, and to use such tactics as they find suitable, while the head office gives that particular district the support of the whole organization. It also provides a way for the head office to send delegates and organizers into unorganized territory without waiting for a charter to be issued for that locality, and in case of all the members in any one locality being blacklisted they do not lose charter or membership, for there is but one charter for lumber workers, and camp delegates who collect dues and initiate members are becoming very numerous. As the result of organization, the members of the L.W.O. are coming to have a good understanding with each other, and they are quietly and coolly figuring just when and where to make their demands.

In Washington, Idaho and Montana, where logs are floated, or “drove,” to the mills, there are generally as many logs cut each winter as can well be taken down the streams during the high water of each summer, and but a few days delay in the drive will mean that large numbers of logs will be left on the banks of the streams till next year, and the worms and rot can do a lot of damage. It is a question with the bosses whether rot in the logs will cost more than the wages demanded. In some places the bosses have decided that it is better to agree to the demand than have no logs this year, and the L.W.O. is making preparations for presenting demands at the right time at other places. The results gained so far by the L.W.O. through organized effort, and the work of education that is being carried on, indicate that the growth in membership will be very rapid. The river drivers on the St. Maries River in Idaho have raised their wages from $3.50 for twelve hours to $5.00 for eight hours.

At the Convention held in Spokane, the pledge was given that if any of the Everett prisoners were convicted, the L.W.O. would bring economic pressure to bear to change the verdict. The convention also adopted a demand for $60 per month and board for all teamsters in the woods, and eight hours work; $5 and board for eight hours work for river drivers, and that all men be paid twice a month in cash or bank checks without any discount.

The Lumber Workers Organization is working along lines that were to some extent mapped out by the Agricultural Workers Organization during the past two years in the harvest fields of the Central states. But in some instances the work is being carried along on entirely new lines for which there is no precedent, and each problem is handled as it arises. The Organization and its methods are so new that the bosses have been unable to find any way to successfully combat it. And the very success that it is making is why the L.W.O. No. 500 is attractive to the lumber jacks.

As this is being written the river drivers are in some places enjoying the benefits of the better conditions they have secured; in some places they are still on strike, and in other places they are waiting till the drives are started before making their demands. There is no disposition to help the bosses break the strikes by going out when there is no demand for labor power. The disposition now is to wait till the bosses are just starting their log drives, and then making a good drive for wages. And the boss knows that the water running to the sea now will never come back to float logs to the mill. It must be taken at the flood to lead on to fortune, and the boss cannot grasp that fortune except he concedes to the lumber jacks a larger portion of the wealth they create.

But more than the demands made for higher wages and better working conditions, the lumber jacks are consciously building their organization for the purpose of taking and operating all the lumber industry in the interest of the working class just as fast as the rest of the working class can be brought to see their economic position in society. The lumber workers know that they cannot go much beyond the most advanced position of other organized workers in industry, but they are determined to keep the L.W.O. in the front of the drive against the bosses, and have in less than three months since their convention been able to obtain some good results, and they know that better results can be obtained in the near future.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v17n12-jun-1917-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf