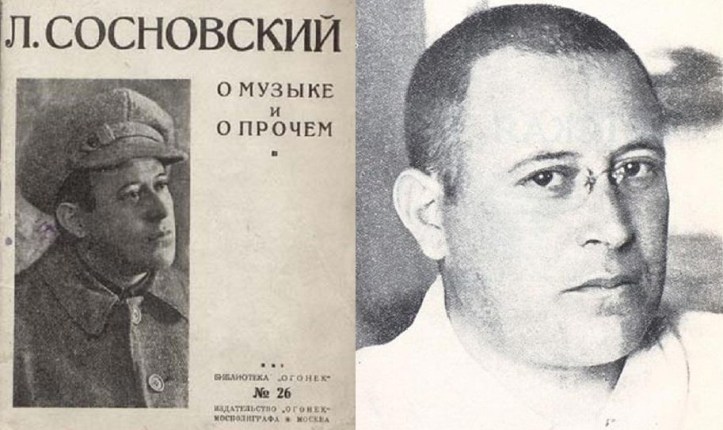

A rare English-translated article from Lev Sosnovsky is this remarkable look into the changes the first years of the revolution brought to one small village in the Kaluga region whose name was changed from ‘Pestilence’ to ‘Rosa Luxemburg’. Veteran Bolshevik Lev Sosnovsky was editor of the Party’s newspaper for peasants, The Poor, and spent much of his time traveling to villages explaining Party policy as a head of the Presidium of All-Russian Central Executive Committee’s Agitprop Department. One of the leading Soviet journalists and editors, Sosnovsky would be one of the best-known figures of the Left Opposition from 1923 until he 1934 when he recanted. Arrested during the Purges, Sosnovsky was executed on July 3, 1937.

“Rasseya” by Lev Sosnovsky from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 6 Nos. 6 & 7. April 1 & 15, 1922.

The following account of actual happenings in provincial Russian communities is taken from a recent issue of “Pravda”. “Rasseya” is the illiterate peasant way of pronouncing and writing “Rossiya”–Russia.

“WE, the citizens of the village Rosa Luxemburg, of the International County of the District of Kaluga, of the province of the same name, send greetings to the Communist International, etc…

Please don’t consider this an invention. This county and this village really do exist. And such a resolution was printed in the papers. In general, in the province of Kaluga, the streets, the counties and the villages have been thoroughly renamed.

“Village of Rosa Luxemburg” comes strange and awkward to the tongue; the same may be said of the village of “The Dekabrists”. But was the former name of this village better when it bore the name “Yazva” (Pestilence)?

In my country, in the province of the Orenburg Cossacks, there were before the Revolution hamlets and settlements, bearing the name “Paris”, “Leipzig”, “Berlin”, and even–Fere-Champenoise, in commemoration of certain battles and treaties. Why the bearded Cossacks should live in a locality with the amazing name of Fere-Champenoise, none of them knows, not even the teacher and the priest. But as to “Rosa Luxemburg” and “The Dekabrists”, the Kaluga people already know something, and as time goes on they will know more.

It took Russia four years to change the “Village of Pestilence” to the “Village of Rosa Luxemburg.”. Why the village had been given the name “Pestilence” I do not know. The dear overlord had probably been angered somehow by his serfs and in his rage he must have rechristened the village with the name of “Yazva”.

Thoughtless people may console themselves with the thought that the name only has been changed and that the village of Pestilence in itself has not changed. Let them take what consolation they can from this notion.

I am glancing through the “Memorial and Yearbook of the Province of Kaluga for 1916.” On page XXIX is printed the list of all the governors from 1776 to the Revolution of 1917. Here are the most striking names:

Prince P.P. Dolgorukov

Prince A.D. Obolensky

Count D.N. Tolstoi

Prince N.D. Golitzin

Privy Councilor A.G. Bulygin

Prince C.D. Gorchakov

Gentleman of the Bedchamber, Chenikayev.

They all ruled over the village of Pestilence. But at present the Province of Kaluga is ruled by the Chairman of the Executive Committee of

the Province, Aleksey Kirillovich Samsonov, a baker, of peasant stock, of the district of Kaluga. His substitute is N.I. Novikov, salesman, of peasant stock, also of the province of Kaluga.

Immediately after the governor there usually followed, let us say, the commander of the garrison, who used to be a brigadier-general.

At present the office of Military Commissar of the province and Commander of the Garrison is in the hands of a workingman, the lithographer H.E. Almazov.

With the permission of the dear gentlemen of the nobility, I will take the liberty–to compare the Marshal of the Nobility–there is no other fitting comparison–with the Chairman of the Provincial Extraordinary Commission–the locksmith I.D. Ossipov, of peasant stock, of the Province of Kaluga.

Instead of the former Police Commissioner–there is the Commander of the Provincial Militia, the painter V.V. Dyuzhikov–who, like all the other ikon-makers, was born in the province of Vladimir.

Among the liberal Zemstvo workers in the province of Kaluga a prominent place was occupied by the Cadet philosopher Prince Eugene Trubetskoy. He was also member of the Supreme Council of the Empire, and was elected from the Province of Kaluga.

If we may place the present Board of Agriculture at the same level with the Zemstvo, then we may declare that the Prince and Philosopher has been replaced by the limping cobbler A.D. Dyudin, in charge of the Provincial Department of Agriculture.

We shall close this list of the provincial authorities of the past and the present by presenting the court authorities of the province.

Instead of the old-time jurist, with his uniform and a diploma, who was the chairman of the district court, today the functions of the Chairman of the Provincial Revolutionary Tribunal are discharged by the printer P.I. Gromov.

Where then are the old masters? Some of them have disappeared, and others are far away.

I was in the commune “The Red Town,” situated in the former estate of the Prince Galitsyn (10 miles from Kaluga). His Excellency has sent word from abroad. He addressed to the Commune a letter, the contents of which are as follows:

“Robbers and bandits!…You may rob without conscience my house, my estate, my cattle. Ge to the devil! But I beg you to spare my ancient linden park. On these linden trees that were planted by my forefathers I will hang you scoundrels as soon as I come back!”

This letter is being preserved in the office of the Provincial Extraordinary Commission and I have advised them to save it as a museum curiosity.

Here is one of the former masters. Near the building of the Executive Committee of the Province there always stands a well dressed coachman. A splendid horse, rubber tires, a peasant’s cloth overcoat, a coachman’s cap of oilcloth, and the hair cut in the Russian peasant manner.

This is the former landed proprietor Unkovsky, the descendant of the Unkovskys who in the sixties, under Alexander II, were the masters of the destinies of the peasants.

“If you please, Comrade, I will give you a ride!” he proposed to Almazov, Military Commander of the Province.

“Get out, Comrade Unkovsky! The whole city knows that you charge 50,000 rubles a ride. They will say immediately that Almazov has become a grafter.” They part amicably, the Military Commander and the cabby. The former dirty lithographer, who was always soiled with ink, and the former sleek gentleman of noble birth whose fine white house is even now visible at the foot of the hill.

Ask Almazov or Samsonov who were their own forefathers, how they were named and they will not answer you. Go to the Lavrentiev Monastery (at present a concentration camp), and you will find there a big row of marble statues at the entrance of the church. All read: Unkovsky, Unkovskaya, Unkovskys….a venerable dynasty. From the aristocratic three-cornered hat with a sword, to the coachman’s oilcloth cap with a whip. “If you please I will give you a ride!”

As you see, the way from the village “Pestilence” to the village “Rosa Luxemburg” is very long. It is not merely a change of the door sign or of the rubber stamp when the nobleman and business man have been removed from the management of the affairs of the Province and their places have been taken and kept for four years by bakers, cobblers, lithographers, locksmiths and painters–all children of poor peasants of the Kaluga province.

Almost the entire personnel of the Administration of Kaluga lives in one apartment, in the house of a former merchant. They live in a kind of Commune by putting all their salaries and food rations into the common fund. They put the rooms in order themselves, arranging the samovars, etc. Their whole mode of living is watched by the whole town. Let one of them have a glass of whiskey, let him leave the house in an unsober condition, let him show himself on the street with an unworthy person, and the entire province will know about it.

Under the dictatorship, the government is rather severe–there is no doubt about that. But the people of the village “Rosa Luxemburg” have quite a different attitude towards the authorities from that of the village “Pestilence.”

Near the village “Pestilence” there lived rich peasants such as Yerokhin, Yevdokimov and others–suburban kitchen-gardeners. Sturdy people, they had erected for themselves comfortable two-story farmhouses. It so happened that the Executive Committee of the Province stepped rather vigorously on their toes by infringing imprudently and illegally upon their property rights.

The Yerokhins found their way to all the high authorities, to the Commissariat of Agriculture, to the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic, to the Council of People’s Commissars, and to the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. They obtained, although only in part, their reinstatement in their rights, after having passed all the legal Soviet instances. But this is not important. More interesting is their attitude towards the provincial authorities.

The Yerokhins entered by force the office of the Chairman of the Provincial Central Executive Committee, shouted, threatened with reprisals on the part of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, and called him a counter-revolutionary for not complying with the decision of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee.

Of course, the Chairman of the Provincial Executive Committee could have simply given a sign and the impertinent kulak would have felt the hand of the Cheka. But in the village “Rosa Luxemburg” they know very well, from the poor man to the kulak [Rich peasant.] and the priest, that the present government is simple, is one of their own people.

What is Samsonov after all? Even the All-Russian Elder M.I. Kalinin [The Chairman of the Russian Central Executive Committee virtually the President of the Soviet Republic–is called by the peasants the Chief “Starosta”–the All-Russian Village Elder.] once came to Kaluga. At one village meeting–as reported by local inhabitants–a disgruntled, irritated peasant began to address Comrade Kalinin with the strongest possible words (I don’t know whether all these words would pass the censor). Kalinin listened and then with the general approval of the meeting, began to reprimand the basely egotistic and capitalistic instincts of the peasant. And in doing so, it is said that Comrade Kalinin did not husband his vocabulary.

The peasants took his side in this dispute and up to the present day remember the All-Russian Elder because of his simplicity and plain words:

“See, he speaks our language! This is a government as it ought to be!”

In the village “Pestilence” it never happened that the head of the supreme government authority of the whole country should quarrel with a peasant in public meeting, and that he should consent to be addressed in not very dignified expressions.

But in the village “Rosa Luxemburg” it has happened.

In the company of Samsonov, the Chairman of the Provincial Executive Committee, we are directing ourselves to one of the Soviet farms. Climbing a steep hill the machine got out of order. We had to walk. At the top of the hill there is a church containing a wonder working ikon. Once upon a time (when the village was called “Pestilence”) the priest and his wife were coining money here. Now the profiteering time is over and here is what is going on now:

From the priest’s house a middle-aged woman came out: the priest’s wife. She walked towards us.

“Comrade Samsonov, would it be possible for me to obtain two dessiatins of land? We were allotted land–but very far from here, while right here in the vicinity there is land that lies idle. It would not be idle with us. Would it not be possible to get it somehow?”

“Will you work it yourself?”

“We ourselves…Why certainly! Just come into our yard and you will see what I am doing with my own hands. Don’t you see how my hands look?”

Indeed, her hands bespoke her hard work; they were covered with callous spots.

We entered the yard. The priest’s wife showed us the felled and uprooted trees, and the earth that was prepared for cultivation.

“Here we will have a kitchen-garden and berries next year. Come to see us next year to have tea and berries with us. I could do much good work, but I have not the land on which to do it.”

“Very well, address us at the Board of Agriculture. We will look it up. But tell me, how did you destroy the trees? For they were all put there to make a fine show in order to invite pilgrims. And this very hill had been thrown up for this purpose.”

“Oh, well, what do I care for show! I would not otherwise have found a place for a kitchen-garden.”

When leaving the priest’s house, I thought to myself:

“In the former days the priest’s wife would not have boasted about her callous hands if she had met the governor. On the contrary, they would have shown the governor their well-manicured nails, their elegant manners, their fine furniture, and given him a splendid dinner. But now every priest’s wife knows that from the village “Rosa Luxemburg,” up to the All-Russian Central Executive Committee in the Kremlin, all the new authorities are looking at hands and paying reverence to those that are callous.”

Russia has changed. It has greatly changed. Let us turn our attention elsewhere for a moment.

A few days ago I received a letter from the Tagan prison, from an old textile worker, I.A. Komarov, with whom once upon a time, before the Revolution, I had worked together in the trade union. The fellow had done wrong, he had gotten into bad company, spent the union’s money, and is now in prison awaiting trial.

He writes: “I feel my weakness and my baseness. But it is very hard for me to sit here in the company of all sorts of rabble. There is not a single worker here. They are all bourgeois, generals, bishops, chinovniks [Tsarist government officials]. Although they may pretend to be workers, they hate them at heart…”

This is what happened in Russia. A worker who had committed an offence, notwithstanding how low he may have fallen, considers it humiliating to be kept in the company of such rabble as generals, bourgeois, bishops, chinovniks. And the latter find it to their advantage to pretend to be workers.

I remember another case also. After Comrade Krassin’s first journey to London, people spoke of an adventure of one of the experts of our trade delegation in that city. He was a former bourgeois, powerful on the stock exchange. In London he wanted to go to the theatre, bought a ticket for one of the stalls and took his seat. But then something happened. They asked him to leave his place. He showed his ticket and his papers. It was of no avail. It turned out he had not come in full dress. Such as he was, he could be admitted only to the places further back, or in the gallery.

Our bourgeois was so indignant with the bourgeois order of civilized England, that involuntarily he cried out:

“Oh, you filthy swine! They should send you some sailors from the Cheka…They would teach you to go in full dress…’ The importance of full dress (frock coat) has been greatly undermined. It has been crowded out by the blouse.

I take the train from Kaluga to Moscow. There are fellow travelers of various kinds. There is a pretty little lady with curls, every moment consulting her mirror (to see whether everything is still in place) and powdering her nose. She talks through her nose, using French expressions. With her are her husband–a military specialist from the Department of General Military Training, and another military specialist from the Provincial Military Committee. It appears that the little lady was a nurse in the hospital, and had found a husband there, who had been one of her typhus patients.

“Under various pretexts I was getting for him four portions each time.”

Into the windows of the car there was shining the moon of Kaluga as a substitute for the non-existing artificial light. And under the shining moon-light, what do you think the conversation was about?

About the kitchen-gardens and potatoes.

“In our Provincial Health Department the soil that was allotted to it turned out to be worthless. No matter how much it might be watered-nothing comes out of it. But the kitchen-garden of the Provincial Military Command is remarkable.”

“Of course, of course…They have been cultivating it for three years. The soil there is thoroughly cultivated. And the discipline there is severe. It happened that one day one of the fellow-workers did not come out to work the garden, and forthwith she was deprived of her part in the crop.”

“You know they have a very good kitchen-garden committee. The chairman is the Artillery General Lau. He turned out to be a first-class gardener just like a professor. And he maintains discipline. In general he has shown great capabilities. He is also a locksmith, a carpenter, a shoemaker…When in official business he has to go to Moscow, he always takes with him a kind of collapsible sleigh which he has manufactured himself. He puts it all together in a stick. And in Moscow he converts it into a sleigh, puts on it his luggage and a few poods of firewood and pulls it across Moscow to the home of his sister.

“I tried the following experiment: I planted the potatoes one yard deep. They said the crop would be extraordinary. I am still waiting.”

“The manure is of great importance…”Yes, the manure,” languidly sighed the little lady and gave herself up to reveries…

In former days I traveled considerably all over Russia, I listened to many conversations between little ladies and elegant officers, but they were never about manure or kitchen-gardens.

And on the outskirts of Kaluga I witnessed an unforgettable living picture. A gay sunny day. On both sides of the macadam road, there is a motley crowd of people busying themselves like ants around the vegetable beds.

You see, all this mixed company are Soviet workers. Songs, shouts, jokes. Colored jackets and scarfs. Further on the color of khaki–the Provincial Military Command. And over there, people blackened by dust and dirt–printers and bricklayers.

The whole field was speckled and dark with its many workers. There was a confused sound of songs, shouts and jokes. The people were digging potatoes, the crop of which was very fine.

It was not a common landscape.

Let us return to the “rulers” of the province. One could say: it is not of importance that they are peasants. But what masters do they make? I assert that these masters are not worse, but better, than the old ones.

The old masters ruled for decades and longer. They had more experience and were also better prepared. The new ones have been at the helm for four years only, and what years they have been!

On the occasion of the third anniversary of the November Revolution there was published at Kaluga a memorial volume under the title “After Three Years.” The book includes some excellent photographs.

The first photograph represents the Council of People’s Commissars of Kaluga. There was such a thing in Kaluga too. The first lisping of the Soviet Government authority.

The second picture represents the entire party organization of Kaluga. It could all find place in one single photograph.

Then come three pictures. The first, the second and the third Communist detachment are departing from Kaluga to the civil war front. And every one of these detachments is more numerous than the organization that originated it. Just as with the mythical Hydra: chop one head off and ten new ones will grow in its place. There are very few workers in the Province of Kaluga. For the most part they were peasants who had left their villages–the village of Rosa Luxemburg and of the Dekabrists. Is it astonishing that the citizens of the village of Rosa Luxemburg of the International County should have some idea of the Communist International, under the banners of which their sons were fighting?

There has not yet been time to introduce a business management. But they have made a beginning, a pretty good beginning. They have greatly extended the telephone system as compared with the times of Trubetskoy and Gorchakov, as well as the electrical power station. The latter was an interesting problem.

The inhabitants of Kaluga had already given up in despair the hope to receive equipment for their station, through the regular channels. “Moscow does not believe in tears.” But all of a sudden there appeared a brisk, sly individual, who promised them, without any trouble, for ready money, to deliver the equipment directly into the yard of the electrical station.

“But where will you get it?”

“That is my secret. But I will tell it to you if you won’t tell the Cheka. It is from the City of N. There are plenty of these things there; why should they lie around idle there? It is better if they will furnish light to Kaluga.”

And he delivered the goods.

The inhabitants of Kaluga repaired the water-supply system and stopped the loss of water.

The little workshops that had shut down were again started. The home industries that had fallen into decay are reviving again. But they are more concerned with the fate of agriculture.

This is the situation. But everybody knows that according to statistical data harmful insects each year destroy about one-third of the crop. The old masters conducted the struggle against this evil in a homeopathic manner, just for make believe.

The new masters took up the work in a serious, scientific manner. Among the Wrangel officers who had been taken prisoners and sent to the concentration camp of Kaluga, there was a learned entomologist. The cobbler Dyudin (in charge of the Department of Agriculture) took him out of that place, warmed him up, handed him new clothing, and gave him a chance to work. They found a big house and made all the necessary arrangements for organizing a “station for the protection of plants against harmful insects.”

When I was invited to look over this child of Kalugan Bolshevism, I made an exclamation of surprise. An astonishingly rich collection of material. A real museum. I am sure that even in Moscow, in the Provincial Department of Agriculture, this branch has not been organized so well. They say that in Moscow the “station” is housed in a few small rooms. And in Kaluga they have provided a big house for this purpose. And their plans, developed by the entomologist, are very far reaching: to create an entire system of such outposts against the enemies of the grain.

This is a symptom of their serious attitude towards agriculture. Moreover, the inhabitants of Kaluga are at present very much interested in improving horse-breeding.

With what pride they took me to the enclosure in which they had collected the best thorough-bred horses, outside the agricultural exhibit!

They led out one horse after another and the members of the Provincial Executive Committee gave the description and pedigree of each one. They spoke of the horses with emotion and affection.

“Here is our Soviet child,” as a fine-looking young stallion was pointed out.

In the “Hermitage of St. Tikhon”, a former nest of “black ravens” [A popular Russian nickname for bold-up men.], a disgusting den of revels and dissipations, there was organized a stud-farm for horses, managed by a Communist working man. And there are many such establishments.

The agricultural exhibition, the first since the revolution, was very successful. In the course of one week it was visited by 85,000 persons. (The exhibition of the People’s Commissariat of Agriculture, held not long ago in Moscow, had fewer visitors). The former exhibitions held in Kaluga had, according to my investigations, not more than 8,000 visitors. The exhibition was accompanied by energetic agricultural propaganda.

I saw in the provinces a few splendidly organized agricultural communes and soviet farms.

In general, the presence of a good manager is felt in the provinces. There is no doubt about that. And it must be said that at present it is much harder to rule the provinces than before. Neither the Governor, nor the Zemstvo chairman, nor the Mayor, ever had the time to supervise such a number of factories, works, stores, agricultural and other enterprises.

You need only to have a talk in Kaluga with the present “governor”–the baker Samsonov. He will expound to you the plan by which he intends steadily and gradually to raise the entire economic life of the province, without leasing anything, and exclusively on the basis of local means and the necessary money advance (for the first half year) from the capital. Out of the surplus obtained from the match factory, he established a paper-mill, later on a glass factory, etc.

It must be pointed out that before the Revolution Kaluga had been going downhill industrially and commercially.

“The nineteenth century was characterized in the history of Kaluga by a gradual decay of industry and by a slow economic dying of the city” (Kaluga, sketch of an historical guide to Kaluga, 1912, pages 46-51).

Hardly any manufacturing of finished products at present goes on at Kaluga. The grain and timber trade have moved to other places. The transit of goods and cattle from the eastern and southern provinces has ceased. “As a result the city is quiet, and has become poorer and poorer.” (Ib. p. 51). This was the inheritance that the new Russia received from the old masters.

Four years of strenuous work without respite, in an atmosphere of desperate struggle.

The old governor and Zemstvo officials would have perished after two or three years of such work. For them a Sunday was always a Sunday. And they had to spend the summer either on their landed estates, or in the health resorts, or abroad. And the week day evenings they spent in clubs or at home over the green table, gambling and drinking.

But the present “governor” and “Zemstvo chairman” cannot relax even on a holiday: he must make a trip to some village, hold meetings, explain matters. And when the summer comes, matters do not become easier for that. There is the sowing campaign, the grain tax, the three fuel weeks, the navigation campaign. (By the way, during the present year the inhabitants of Kaluga used the river Oka for rafting timber, a thing that had not been practised for a long time, and the results were very good.) Thus there is no rest even in summer.

After all, to what “estate” would the present “governor” go for the summer? In the village where he was born his hut has gone to pieces, his family is starving, and he is unable to help them–so it is better for him to stay away. The neighbors sneer at the family: “Well, why doesn’t he help you to buy a little horse? After all, isn’t he the government? The most important man in the province!”

And at home they sometimes suppress a tear: “Other people succeed in improving their little farm; but we have nobody…”

This is how the new Russia and its government lives and works.

We are living in the very thick of life and have no opportunity merely to look on. What has changed in the last four years? Everything around us has greatly changed.

It will not be possible to drive provincial Russia back to the old stable. Let Prince Golitsyn stop thinking of his old ancestral linden trees, on which he threatens to hang the Communists of Kaluga. The linden trees will blossom just as well without him. Except that it is now a little gayer under the linden trees. The youth of Kaluga enjoy life there, and the village of Rosa Luxemburg organizes meetings and sociables under the linden trees, a thing which under the old masters could not even be dreamed of.

I can foretell his destiny to Prince Golitsyn. He will perish somewhere in the gutter, after he has eaten up his last resources, abandoned even by his children. For the young princely generation will go back to Russia, they will obtain pardon from the baker Samsonov and the cobbler Dyudin and they will be accepted as members of the Commune “The Red Little Town”, where the Golitsyns were born. The muzhiks of Kaluga are good-natured people, not like their princes. They will forgive the old wrongs, and will not hang anybody for the age-long oppression. “Work, Comrade Golitsyn, earn a piece of bread”.

The longing and the anguish of the Golitsyns may be felt from their papers published abroad. We see there heart-stirring verses such as this: “The dust of Moscow on the band of an old hat”…

With tears of emotion the poet, while staying in Paris, looks at the remnants of the “dust of Moscow,” all that remains of the things he carried away. All the rest is gone to decay. He feels himself attracted toward the earth of Moscow. He will not hold out, he will come back repentant and will kiss and cover with hot tears this earth that has assumed a new face, in torments and sufferings.

Dear Russia, the land of the Dyudins and Samsonovs who were born in the village of Pestilence and at present live in the village of the Dekabrists and the village of Rosa Luxemburg!

Accept now, at the fourth anniversary of your life, a tender greeting from your sons, the fighters for your liberation!

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v4-5-soviet-russia%20Jan-Dec%201921.pdf