Sherman reports on the violence of the state and and vigilantes against labor organizations and the left during the summer of mass strikes in 1934.

‘The Growth of Terror Against the Rising Strike Wave in the U.S.A’ by B. Sherman from Communist International. Vol. 11 No. 17. September 5, 1934.

A LITTLE over a year has passed since the inauguration of the N.R.A., which was hailed as a new Bill of Rights for Labor, and the wave of strike struggles sweeping the United States is continually rising and developing to new heights of intensity. The Roosevelt Government, which was so lavish in its demagogy and promises to the workers, is more and more revealing itself as the instrument of finance capital in carrying through the offensive against the working class for the purpose of shifting the burdens of the crisis to the shoulders of the toiling masses. Already in July, 1933, the Central Committee of the C.P. of the U.S.A., in analyzing the New Deal, pointed out the tendencies for the development towards fascism, not the least of which was the attempt to outlaw strikes by compulsory arbitration. The failure of the arbitration boards and legislation to stem the tide of struggle has called forth the use of the most violent measures for the suppression of the workers’ struggles. There is today hardly a single strike, no matter how small, or unemployed demonstration that is not met by the mobilization of the police, who use tear gas bombs and guns, and the increasing use of the National Guard with full war equipment. The toll of dead and injured in these numerous pitched battles (Alabama, Toledo, Minneapolis, Wisconsin, Pacific Coast, etc.) , between the workers and the armed forces of the employers and the State is constantly mounting, and the scene of these struggles often resembles the front lines of a war area, with the erection of barricades, mounting of machine guns, troops patrolling with fixed bayonets, etc. In addition, we are now witnessing a more or less intense drive particularly in the South and on the Pacific Coast, against the Communist Party. This raises as an important problem for the Party the question of organizing a struggle against the terror, and other tasks relative to the growth of fascist tendencies in the United States.

A whole series of developments point to the increasing use of fascist methods against the working class and especially the revolutionary organizations. Fascist organizations, which are estimated to number over a hundred, have sprung up all over the United States, some of them organizationally and ideologically connected with the Nazis and with the Italian fascist movement, others of a specifically “American” character such as the Ku Klux Klan and the Vigilantes. Big business interests in the U.S.A. have been revealed as having financial connections with some of these organizations. The hand of the Roosevelt Administration in the fascization process can be seen in the bill passed by Congress and signed by the President handing over 75,000 rifles to patriotic organizations such as the American Legion, which have always stood in the forefront of crusades against the Communist Party, and for the purpose of breaking strikes. The Federal police forces are now being strengthened, and new appropriations have recently been made by Congress under the guise of fighting the “crime wave”. The local police in all industrial centers are being provided with riot guns, tear gas, armored cars, and are trained in riot duty.

Only recently the “liberal” demagogue, Mayor LaGuardia of New York city, faced with a rising tide of struggles for unemployment relief, launched a campaign of police terror against the unemployed and attempted to prohibit meetings from being held in Union Square, the traditional site of working class demonstrations in New York. The police were given orders to shoot into these demonstrations, and were threatened with dismissal for showing any leniency. A special “police rifle regiment” of 1,200 is being trained for “riot duty” against the workers, and Mayor LaGuardia recently attempted to introduce a system of registering all trade union officials with the police; it was only after a storm of protest arose that he was forced to abandon this reactionary scheme. The capitalist press began to whip up an anti-Red hysteria with provocative articles against “alien agitators”. The magazine Today (May 26 issue), edited by Raymond Moley, chief of Roosevelt’s “brain trust”, carried an extremely provocative leading article by the socialist, McAllister Coleman, called “Communist Strikes”, attempting to show that it is the Communists who provoke violence and they must be dealt with accordingly. Moley, in a signed editorial in the same issue, writes: “Communism in the body politic grows in much the manner of an infection in the human system. In each case there is a germ, and it is well to attack it directly.” Using demagogy to cover up his real meaning, Moley advises that fascist tendencies should be covered up more skilfully. He says:

“Avoid not only injustice, but the appearance of injustice. Maintain the process of democracy in a healthy condition, no matter how much power the government assumes. Let every government official and every government agency learn to make clear to the public what he is doing and why he is doing it.”

This advice to use phrases about “democracy” cover up strike-breaking and the introduction of measures of fascization is being applied by the Roosevelt government in the present strike wave.

In the month of May the strikes of the Alabama miners, the Toledo auto-parts workers, the Pacific Coast maritime workers, and the Minneapolis truck drivers were met with the fiercest attacks by the police and the National Guard, and in Birmingham, Alabama, the authorities opened a drive against the Communists which culminated in many arrests of Negro and white workers, and raids on the headquarters of the International Labor Defense which were wrecked. Even the noted playwright, John Howard Lawson, was arrested because he went to Birmingham to investigate and write an account of the terror.

The mass resentment against this wave of terror forced Congressman Ernest Lundeen, Farmer-Laborite of Minnesota, to introduce a resolution into the House of Representatives on May 15 condemning the use of “private armies” against strikes, and authorizing an investigation of the terror by “private armies” or the National Guard against the workers on strike. The Party began to organize a mass protest campaign against the terror. It looked upon the Lundeen resolution as a means to focus the attention of the whole country on the savage assaults being made on the working class, and to stimulate a mass protest movement against the terror. However, some serious errors were made in the Daily Worker when it first took up the question. An editorial in the Daily Worker (May 17) which hailed the introduction of the Lundeen resolution into Congress as a “victory” for the working class in its fight against terrorism, limited the question of the fight against the terror to organizing a movement in support of a Congressional investigation, and created the illusion that a Congressional investigation might bring in a report favoring the workers and end the terror conditions. The Central Committee corrected this opportunist approach to the question, in a statement of the Political Bureau (Daily Worker, May 23), which pointed out that the struggle against the terror must have the objective of organizing mass resistance of the working class involving the broadest masses, and that the utilization of the Lundeen resolution could only be at best a supplementary means of helping to organize a protest campaign against the armed attacks on the workers. After this correct criticism of opportunist errors, however, the Daily Worker had not one word to say about the Lundeen resolution, forgot about it completely, and made no effort to utilize it as it should have during the following weeks when the strike struggles and clashes with the armed forces of the state were becoming increasingly frequent.

These struggles reached their height in the magnificent strike of the Pacific Coast maritime workers and the general strike of over 125,000 workers in San Francisco and vicinity which took place on July 16, in support of the longshoremen and seamen. Due to the militant rank-and-file leadership of the maritime workers’ strike, which united the workers in the reformist and revolutionary unions under the leadership of a joint strike committee with representatives from ten Maritime unions, the strike was subjected from the first to a heavy barrage from the capitalist press because of “Communist leadership”.

Their tactics were to attempt to break up the united front of the strikers and to split the rank and file away from the militant leadership, among whom were some Communists. This would have been the best means of breaking the backbone of the strike and driving the workers back to work under a sell-out agreement such as the A.F. of L. officials were vainly trying to put over. These tactics did not succeed, and the authority and prestige of the Communist Party constantly grew, as could be seen by the fact that the strike committee of the longshoremen in San Francisco adopted the Western Worker, official weekly organ of the Communist Party on the Pacific Coast, as their strike organ. Moreover, a powerful sentiment of solidarity swept the ranks of the workers, following the killing of two strike pickets, one a member of the Communist Party, and 40,000 workers participated in the funeral. In spite of the frantic efforts of the A.F. of L. leaders to prevent it, this solidarity movement finally developed into a general strike in San Francisco and neighboring cities, and in votes for similar action by the local unions of Portland, Seattle and San Pedro.

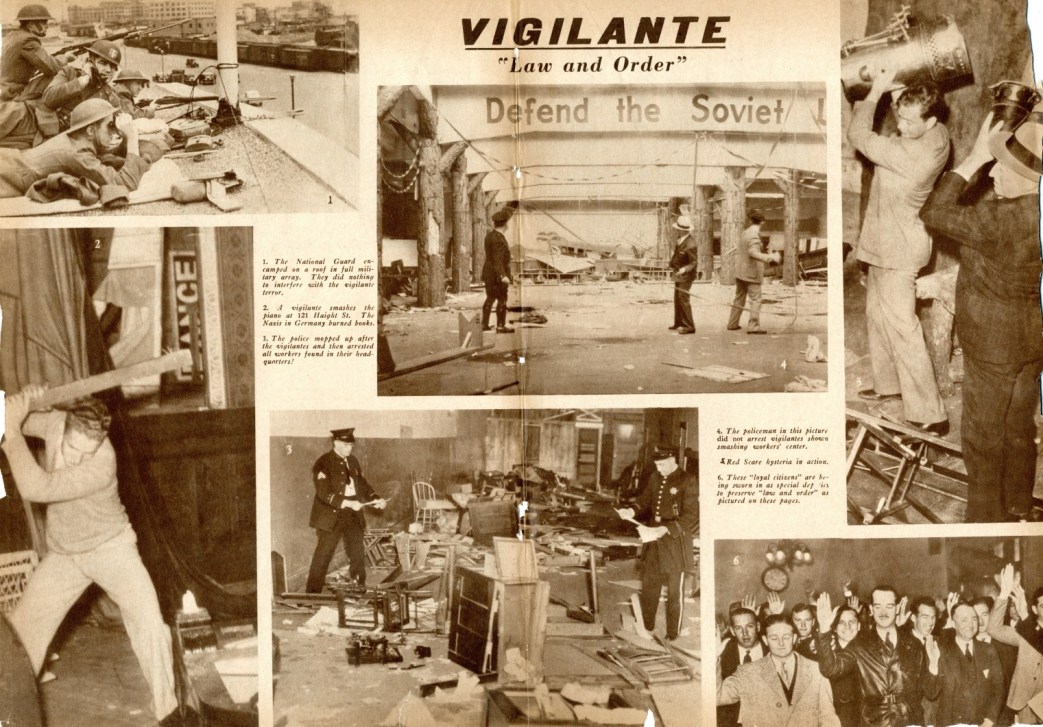

It was then that the drive against the strikers and the revolutionary workers’ organizations was opened in all its fury by the joint efforts of the employers, the government, and the capitalist press, with the able assistance of the A.F. of L. officials who were from the first scheming to end the strike and betray the maritime workers to government arbitration. The press attempted to whip up an anti-Communist hysteria, and the Governor and Mayor made radio speeches denouncing the general strike as a “Communist attempt at revolution”. General Hugh Johnson, head of the N.R.A., came to the strike scene and in a provocative speech at the University of California called upon the A.F. of L. leaders to wipe out “subversive elements” from the trade unions, and openly encouraged attacks by fascist gangs against revolutionary workers. He branded the general strike as an “insurrection” and demanded that it be brought to a close, as the Federal Government would not countenance such threats. President William Green of the A.F. of L. issued a statement that the general strike was unauthorized by the A.F. of L. and in violation of its statutes. Mayor Rossi of San Francisco organized a Committee of 500 to combat “the Communists’ attempt to starve the people”. Governor Merriam of California ordered all available troops of the National Guard into the strike area and gave them orders to “shoot to kill”. Troops of the U.S. Army were also held in readiness in their barracks. Secretary of Labor Perkins telegraphed that the Federal Government would cooperate in the rounding up of “alien agitators” and deporting them. With the stage thus set, beginning with the second day of the general strike, the terror struck. Along the entire Pacific Coast, from Seattle to San Diego, as if by plan, simultaneous raids were carried out within a period of a few days along a 2,000-mile front against headquarters of the Marine Workers Industrial Union, the Communist Party, the longshoremen’s strike headquarters, and many other working class organizations. Fascist gangs of “Vigilantes” destroyed and burned at will, beat up any workers they found in the hall, and even carried through raids against the homes of revolutionary workers. These raids were followed up by “mopping up” operations of the police, who finished the job of destruction if anything had been overlooked by the fascist gangs, and arrested all workers found on the premises. The press reports about 500 arrests were made on the Pacific Coast. The printing plant of the Western Worker in San Francisco was burned to the ground, as were the headquarters of the Finnish Workers Club in Berkeley. Some of the Communists arrested were charged with criminal syndicalism, which carries heavy prison sentences, and the Press reports that fourteen workers have already been ordered to be deported by the Federal authorities in San Francisco. The authorities announced that all meetings of the Communist Party in San Francisco would be prohibited, and that they would not be allowed to conduct an election campaign, although the Communist Party candidates are officially on the ballot in California.

That the terror was merely a preliminary for the breaking of the strike could be seen by the fact that on the day following the beginning of the raids, the A. F. of L. leaders railroaded a motion through the General Strike Committee calling for submitting the strikers’ demands to arbitration, and a day later a motion was carried to call off the general strike. Although the press spread the slander that the raids were carried through by A.F. of L. workers who were incensed at the Communists, the real sentiments of the workers could be seen in the close margin by which the motions of the A.F. of L. misleaders carried even in a committee that was packed with A.F. of L. officials; the vote on the question of arbitration was 207 to 180, and on the calling off of the general strike, 191 to 176. That the drive was carried through by the closest cooperation between the employers and the government, could be seen by the fact that a prominent leader of the Industrial Association already hinted that raids would take place before they actually began, and the police timed their arrival at the workers’ headquarters a short time after the fascists had completed their work of destruction. The role that the A.F. of L. leaders played in launching the fascist attacks is revealed in the July 8 issue of Editor and Publisher in an article which described the role of the “Newspaper Publishers Council” under the leadership of John Francis Neyland, attorney for the red-baiting Hearst newspapers, in breaking the strike. It says:

“Under Mr. Neyland’s leadership plans were made to crush the revolt. Mr. Neyland entered into negotiations with conservative labor leaders…Conservative labor leaders welcomed this help, as they realized that Communists in control of maritime unions had stampeded other unions by saying this was the time for organized labor to take its place in the sun. Newspaper editorials built up the strength and influence of the conservative leaders and aided in splitting the conservative membership away from the radicals.”

The newspaper publishers held a conference with General Johnson, following which the latter made his provocative speech which gave the cue to the fascist gangs. Editor and Publisher describes the success of the plan:

“The strategy of Mr. Neyland and the publishers’ council had now begun to work…On Thursday the general strike was called off in San Francisco and the next day in the East Bay area. As the strike collapsed the publishers’ council endeavored to get things moving again.”

Since the ending of the strike the AF. of L. leadership has opened a campaign throughout the country to drive Communists out of the reformist unions, following the advice given them by General Hugh Johnson, head of the N.R.A.

Already before the general strike, the Party organized a nationwide campaign of protest against the shooting of workers and in support of the Pacific Coast strikers. As the general strike movement gained headway, the Party strove to organize a broad united front movement including the Socialist and AF. of L. workers in support of the strike. In Camden, N.J., these efforts resulted in the organization of a united front demonstration called jointly by a united front committee in which were represented the Central Labor Union, the Communist Party, the Socialist Party, and revolutionary, reformist and independent unions. In New York City, six defense organizations including the Socialists, I.W.W., Musteites, the liberals, together with the International Labor Defense joined in a protest campaign against the terror wave, and formed a Committee for Workers Rights. The Party again and again raised the question of the Socialist Party joining in a united front against the red-baiting campaign which was unprecedented since the Palmer raids in 1919. Many District and local organizations of the Party also approached the Socialist organizations. The pressure was so great, that, although the Socialist Party leadership refused to reply to the united front offer of the Communist Party, the Socialist leaders were forced to make statements in the press and on the radio against the attacks on the Communist Party on the Pacific Coast. On the whole, however, the campaign of the Party was not on a sufficiently broad basis, and with few exceptions did not as yet succeed in drawing in the Socialist and A.F. of L. workers.

The Pacific Coast strike experiences and subsequent events (martial law declared in Minneapolis and Kohler, Wis., shootings in Cleveland, etc.), show that the Party must seriously undertake to organize a mass struggle against the rising wave of a terror launched against the working class movement in the United States. This raises as a central question the organization of a fight for the defense of the democratic rights of the workers, and the development of a real united front for struggle against the increasing tendencies toward fascism, linking this up with the struggle for economic demands. It is necessary to pay more attention to the growth and activities of the numerous fascist organizations in the United States; we must watch more closely their organization and program if we are to combat the growth of their influence among these strata most susceptible to the spread of fascist ideology, the petty bourgeoisie, veterans, farmers, professionals, etc., and win these elements to the side of the working class.

While the Party raised the slogan of organizing mass self-defense against attacks on workers’ meetings and headquarters, the raids caught the Party unprepared and no serious resistance could be organized against the fascist gangs, even when the headquarters of the Marine Workers Industrial Union and the International Longshoremen’s Association, the center for thousands of strike pickets, were raided. The slogan of mass self-defense against the terror must be translated into actual organization and put into action. Only the mobilization of the masses, Negro and whites, for the organization of workers’ self-defense groups based upon the factories, trade unions, and other mass organizations, can defeat the terror. A nationwide protest movement against these attacks must include A.F. of L. and Socialist workers, and every trade union local and Socialist Party local must be approached to join in united front action with the revolutionary workers.

In order to insure uninterrupted leadership for the struggles of the workers the Party must prepare itself to function under conditions when more and more such attacks can be expected. In the main, the Party organizations in the South and on the Pacific Coast continued to function under difficult conditions. In San Francisco, the Western Worker was issued in mimeographed form immediately after the printing plant was destroyed, and illegal leaflets were issued during and after the general strike. The leadership remained intact in spite of mass arrests, but this is because the Party in the South and in California is already accustomed to working for some time under semi-legal and illegal conditions. It is necessary that the whole Party transform itself into readiness to function under any and all circumstances, under conditions of the sharpest repression, so as to maintain continuous contact with the workers and guide their struggles.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-11/v11-n18-sep-20-1934-CI-USA-grn-riaz-oc.pdf